BALANTA LAW

1. Balanta people, as all other human beings, were born equal and with complete freedom of choice and action.

2. When the ancient Balanta ancestors grew in number and began to live in the same place with other people (42,000 BC to 3,100 BC), a few restrictions were accepted by common consent, over time. These were the first “laws” in human society.

3. Generally speaking, laws are rules that the people in a society believe are important enough for the society to enforce. There is a purposeful and strong connection between law and that society's morality.

4. The only restrictions on Balanta people were, and still are: Balanta must not injure or kill anyone; Balanta must not steal or damage things owned by someone else; Balanta must be honest in interactions and must not swindle anyone.

5. The restrictions emerged from common consent and derived from Balanta’s spiritual system called The Great Belief. Today, this is called “Natural Law”

6.

EGYPTIAN LAW

7. The Mesintu or “Followers of Horus at Edfu” were the first to violate the Natural Law and develop a new legal code based on religious principles which they kept secret. From the Mesintu, a hierarchical system of social organization developed, and a system of Egyptian law was based on the central cultural value of ma’at (harmony). At the top of the judicial hierarchy was the king, the representative of the gods and their divine justice, and just beneath him was his vizier. The Egyptian vizier had many responsibilities and one of them was the practical administration of “justice”. The vizier heard court cases himself but also appointed lower magistrates. The legal system formed regionally at first, in the individual districts (called nomes) and was provided over by the governor (nomarch) and his steward.

8. By the time of the Middle Kingdom period in Egypt, the courts which administered the law were the seru (a group of elders in a rural community), the kenbet (a court on the regional and national level) and the djadjat (the imperial court). If a crime were committed in a village and the seru could not reach a verdict the case would go up to the kenbet and then possibly the djadjat but this seems a rare occurrence. Usually, whatever happened in a village was handled by the seru of that town. The kenbet is thought to have been the body which made the laws and meted out punishments on a regional (district) level as well as a national level and the djadjat made the final ruling on whether a law was legal and binding in accordance with ma’at.

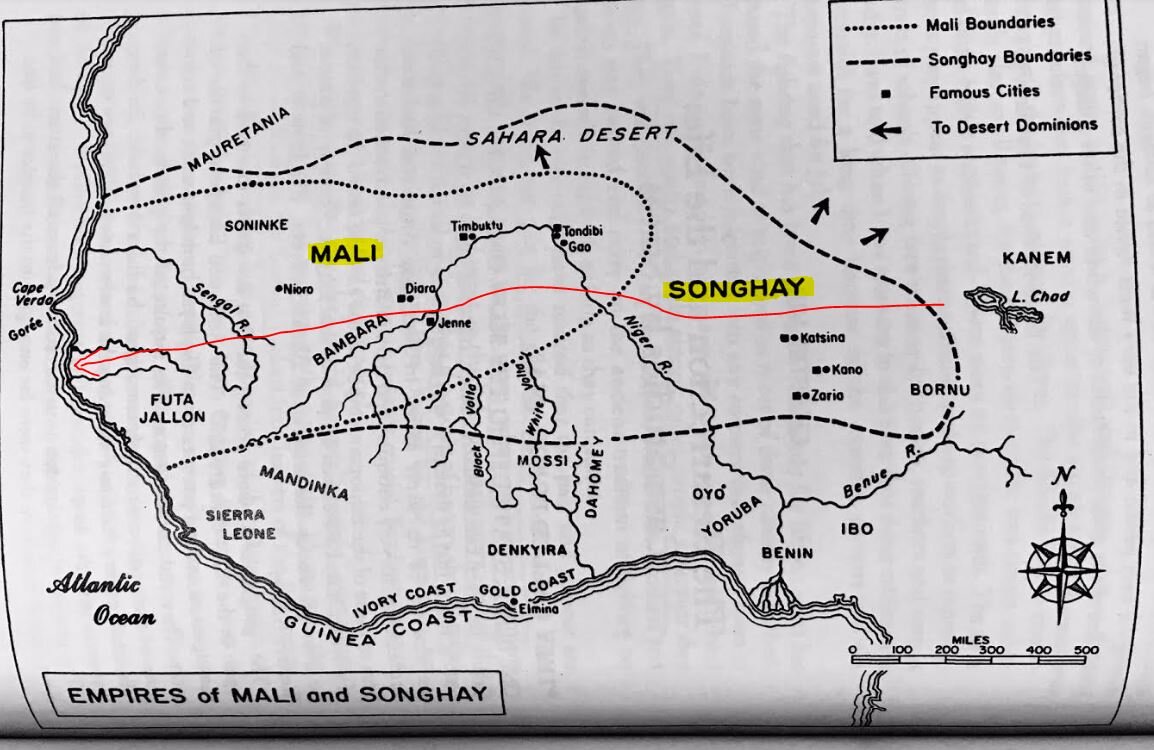

9. The Egyptian hierarchy system was rejected by the Balanta because of the inequality it produced. For the Balanta, the family is the sole effective social and political unit. . . . All important decisions amongst the Balanta were, and still are taken by a Council of Elders. To become a member of the Council of Elders, the person must be initiated during the Fanado ceremony.

10. Balanta people successfully lived and defended their culture governed by Natural Law from the time of their first major conflict with the Mesintu in 3200 BC and against successive persecutions from the Themehu (Libyans), the Shashu and Habiru (Hyksos), Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Christians, Moslems, Magumi of Duguwa (Kanem) and Tumagera, Ma-Ba-U (Hausa), Soninke of Wagadu (Ghana), Tuareg (Berbers), Almoravids in Wagadu (Ghana), Keita Clan (Mali), the Sunni Dynasty (Songhay), the Askia Dynasty (Songhay), the Moors, Fulbe (Fulani coming from the west), and, by the twelfth century, the Manding of the Kaabu Kingdom during what is called The Balanta Migration Period.

11. The latter part of the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt is simply one long, slow, decline into chaos until the country was annexed by Rome in 30 BCE and became another province of their empire.

ROMAN LAW

12. Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the Corpus Juris Civilis (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I. Roman law forms the basic framework for civil law.

13. Before the Twelve Tables (754–449 BC), private law comprised the Roman civil law (ius civile Quiritium) that applied only to Roman citizens, and was bonded to religion; undeveloped, with attributes of strict formalism, symbolism, and conservatism, e.g. the ritual practice of mancipatio (a form of sale). The jurist Sextus Pomponius said, "At the beginning of our city, the people began their first activities without any fixed law, and without any fixed rights: all things were ruled despotically, by kings". It is believed that Roman Law is rooted in the Etruscan religion, emphasizing ritual. The patricians (from Latin: patricius) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. According to Livy, the first 100 men appointed as senators by Romulus were referred to as "fathers" (Latin "patres"), and the descendants of those men became the patrician class. According to other opinions, the patricians (patricii) were those who could point to fathers, i.e. those who were members of the clans (gentes) whose members originally comprised the whole citizen body. The patricians were distinct from the plebeians because they had wider political influence, at least in the times of the early Republic. During the middle and late Republic, as this influence gradually eroded, plebeians were granted equal rights in most areas, and even greater in some. Patricians historically had more privileges and rights than plebeians. At the beginning of the Republic, patricians were better represented in the Roman assemblies, only patricians could hold high political offices, such as dictator, consul, censor, and all priesthoods (such as Pontifex Maximus) were closed to non-patricians. There was a belief that patricians communicated better with the Roman gods, so they alone could perform the sacred rites and take the auspices. This view had political consequences, since in the beginning of the year or before a military campaign, Roman magistrates used to consult the gods. Livy reports that the first admission of plebeians into a priestly college happened in 300 BC with the passage of the Lex Ogulnia, when the college of Augurs raised their number from four to nine. The distinction between patricians and plebeians in Ancient Rome was based purely on birth. Although modern writers often portray patricians as rich and powerful families who managed to secure power over the less-fortunate plebeian families, plebeians and patricians among the senatorial class were equally wealthy. As civil rights for plebeians increased during the middle and late Roman Republic, many plebeian families had attained wealth and power while some traditionally patrician families had fallen into poverty and obscurity.

14. The plebeian tribune, C. Terentilius Arsa, proposed that the law should be written, in order to prevent magistrates from applying the law arbitrarily. After eight years of political struggle, the plebeian social class convinced the patricians to send a delegation to Athens, to copy the Laws of Solon; they also dispatched delegations to other Greek cities for like reason. In 451 BC, according to the traditional story (as Livy tells it), ten Roman citizens were chosen to record the laws (decemviri legibus scribundis). While they were performing this task, they were given supreme political power (imperium), whereas the power of the magistrates was restricted.] In 450 BC, the decemviri produced the laws on ten tablets (tabulae), but these laws were regarded as unsatisfactory by the plebeians. A second decemvirate is said to have added two further tablets in 449 BC. The new Law of the Twelve Tables was approved by the people's assembly. The original text of the Twelve Tables has not been preserved. The tablets were probably destroyed when Rome was conquered and burned by the Gauls in 387 BC. The fragments which did survive show that it was not a law code in the modern sense. It did not provide a complete and coherent system of all applicable rules or give legal solutions for all possible cases. Rather, the tables contained specific provisions designed to change the then-existing customary law. Although the provisions pertain to all areas of law, the largest part is dedicated to private law and civil procedure. Laws include Lex Canuleia (445 BC; which allowed the marriage—ius connubii—between patricians and plebeians), Leges Licinae Sextiae (367 BC; which made restrictions on possession of public lands—ager publicus—and also made sure that one of the consuls was plebeian), Lex Ogulnia (300 BC; plebeians received access to priest posts), and Lex Hortensia (287 BC; verdicts of plebeian assemblies—plebiscita—now bind all people).

ENGLISH COMMON LAW

15. The English common law originated in the early Middle Ages in the King’s Court (Curia Regis), a single royal court set up for most of the country at Westminster, near London. Like many other early legal systems, it did not originally consist of substantive rights but rather of procedural remedies.

16. The Anglo-Saxons, especially after the accession of Alfred the Great (871), had developed a body of rules resembling those being used by the Germanic peoples of northern Europe. Local customs governed most matters, while the church played a large part in government. Crimes were treated as wrongs for which compensation was made to the victim.

17. The common law of England was largely created in the period after the Norman Conquest of 1066. The Normans spoke French and had developed a customary law in Normandy. They had no professional lawyers or judges; instead, literate clergymen acted as administrators. Some of the clergy were familiar with Roman law and the canon law of the Christian church, which was developed in the universities of the 12th century. Canon law was applied in the English church courts, but the revived Roman law was less influential in England than elsewhere, despite Norman dominance in government. This was due largely to the early sophistication of the Anglo-Norman system. Norman custom was not simply transplanted to England; upon its arrival, a new body of rules, based on local conditions, emerged. A period of colonial rule by the mainly Norman conquerors produced change. Land was allocated to feudal vassals of the king, many of whom had joined the conquest with this reward in mind. Serious wrongs were regarded mainly as public crimes rather than as personal matters, and the perpetrators were punished by death and forfeiture of property. The requirement that, in cases of sudden death, the local community should identify the body as English (“presentment of Englishry”)—and, therefore, of little account—or face heavy fines reveals a state of unrest between the Norman conquerors and their English subjects. Government was centralized, a bureaucracy built up, and written records maintained. Elements of the Anglo-Saxon system that survived were the jury, ordeals (trials by physical test or combat), the practice of outlawry (putting a person beyond the protection of the law), and writs (orders requiring a person to appear before a court. Important consolidation occurred during the reign of Henry II (1154–89). Royal officials roamed the country, inquiring about the administration of justice. Church and state were separate and had their own law and court systems. This led to centuries of rivalry over jurisdiction, especially since appeals from church courts, before the Reformation, could be taken to Rome.

18. During the critical formative period of common law, the English economy depended largely on agriculture, and land was the most important form of wealth. A money economy was important only in commercial centres such as London, Norwich, and Bristol. Political power was rural and based on landownership. Land was held under a chain of feudal relations. Under the king came the aristocratic “tenantsin chief,” then strata of “mesne,” or intermediate tenants, and finally the tenant “in demesne,” who actually occupied the property. Each piece of land was held under a particular condition of tenure—that is, in return for a certain service or payment. Succession to tenancies was regulated by a system of different “estates,” or rights in land, which determined the duration of the tenant’s interest. Title to land was transferred by a formal ritual rather than by deed; this provided publicity for such transactions. Most of the rules governing the terms by which land was held were developed in local lord’s courts, which were held to manage the estates of the lord’s immediate tenants. The emergence of improved remedies in the King’s Court during the late 12th century led to the elaboration and standardization of these rules, which marked the effective origin of the common law.

19. The pace of change in the 13th century led to the passage of statutes to regulate matters of detail. Because a significant proportion of disputes in the common-law courts were related to the occupation of land, the land law was the earliest area of law to elaborate a detailed set of substantive rules, eventually summarized in the first “textbook” of English law, Littleton’s Tenures, written by Sir Thomas Littleton and originally published in 1481. Primogeniture—i.e., the right of succession of the eldest son—became characteristic of the common law. It was designed only for knight-service tenures but was inappropriately extended to all land. This contrasted with the widespread practice on the Continent, whereby all children inherited equal shares.

20. The unity and consistency of the common law were promoted by the early dominant position acquired by the royal courts. Whereas the earlier Saxon witan, or king’s council, dealt only with great affairs of state, the new Norman court assumed wide judicial powers. Its judges (clergy and statesmen) “declared” the common law. Royal judges went out to provincial towns “on circuit” and took the law of Westminster everywhere with them, both in civil and in criminal cases. Local customs received lip service, but the royal courts controlled them and often rejected them as unreasonable or unproved. Common law was presumed to apply everywhere until a local custom could be proved. This situation contrasted strikingly with that in France, where a monarch ruled a number of duchies and counties, each with its own customary law, as well as with that in Germany and Italy, where independent kingdoms and principalities were also governed by their own laws.

This early centralization also diminished the reception of Roman law in England, in contrast to most other countries of Europe after the decline of feudalism. The expression “common law,” devised to distinguish the general law from local or group customs and privileges, came to suggest to citizens a universal law, founded on reason and superior in type.

By the 13th century, three central courts—Exchequer, Common Pleas, and King’s Bench—applied the common law. Although the same law was applied in each court, they vied in offering better remedies to litigants in order to increase their fees.

The court machinery for civil cases was built around the writ system. Each writ was a written order in the king’s name issued from the king’s writing office, or chancery, at the instance of the complainant and ordering the defendant to appear in the royal courts or ordering some inferior court to see justice done. It was based on a form of action (i.e., on a particular type of complaint, such as trespass), and the right writ had to be selected to suit that form. Royal writs had to be used for all actions concerning title to land.

21. Under Henry III (reigned 1216–72), an unknown royal official prepared an ambitious treatise, De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliae (c. 1235; “On the Laws and Customs of England”). The text was later associated with the royal judge Henry de Bracton, who was assumed to be its author. It was modeled on the Institutiones (Institutes), the 6th-century Roman legal classic by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, and shows some knowledge of Roman law. However, its character—as indicated by the space devoted to actions and procedure, to the reliance on judicial decisions in declaring the law, and to statements limiting absolute royal power—was English. Bracton abstracted several thousand cases from court records (plea rolls) as the raw material for his book. The plea rolls formed an almost unbroken series from 1189 and included the writ, pleadings, verdict, and judgment of each civil action. Edward I (reigned 1272–1307) has been called the English Justinian because his enactments had such an important influence on the law of the Middle Ages. Edward’s civil legislation, which amended the unwritten common law, remained for centuries as the basic statute law. It was supplemented by masses of specialized statutes that were passed to meet temporary problems.

Growth of chancery and equity

22. Since legal rules cannot be formulated to deal adequately with every possible contingency, their mechanical application can sometimes result in injustice. In order to remedy such injustices, the law of equity (or, earlier, of “conscience”) was developed. The principle of equity was as old as the common law, but it was hardly needed until the 14th century, since the law was still relatively fluid and informal. It has been said that what was truly new was not equity but law. As the law became firmly established, however, its strict rules of proof (see evidence) began to cause hardship. Visible factors of proof, such as the open possession of land and the use of wax seals on documents, were stressed, and secret trusts and informal contracts were not recognized.

Power to grant relief in situations involving potential injustices lay with the king and was first exercised by the entire royal council. Within the council, the lord chancellor—a leading bishop—led the meetings and, probably as early as the reign of Richard II (1372–99), dealt personally with petitions for relief. Eventually the chancellor’s jurisdiction developed into the Court of Chancery, whose function was to administer equity. Much of the work concerned procedural delays and irregularities in local courts, but gradually the power to modify the operation of the rules of common law was asserted.

The chancellor decided each case on its merits and had the right to grant or refuse relief without giving reasons. Common grounds for relief, however, came to be recognized. They included fraud, breach of confidence, attempts to obtain payment twice, and unjust retention of property.

Proceedings began with bills being presented by the plaintiff in the vernacular language, not Latin; the defendant was then summoned by a writ of subpoena to appear for personal questioning by the chancellor or one of his subordinates. Refusal to appear or to satisfy a decree was punished by imprisonment. Because the defendant could file an answer, a system of written pleadings developed.

CANON LAW

23. During the 12th Century, Pope Alexander III begins reforms that would lead to the establishment of “Canon Law” – ecclesiastical law laid down by papal pronouncements. Wikipedia defines Canon Law as “a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (Church leadership), for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members.” SEE NOTE BELOW

24. The fifteenth-century European legal corpus, by conceding dominium to infidels and pagans, implicitly recognized a sovereign African existence that preceded the human calculus transforming subjects into captives and slaves. Based on an established corpus of thought, law, and theology configuring Christian institutional relations with non-Christians, African polities wielded legal tender in the Christian imaginary. . . .

25. Even as extra ecclesiam, Guinea’s inhabitants, both infidels and pagans, had natural rights. In asserting its authority over the extra ecclesiam, who, in turn, acquired additional obligations and rights, the Church complicated matters.

26. At the most elemental level, natural law acknowledged native (African) sovereignty even as Christian thought, theology, and law sanctioned the enslavement of Africans. . . . .

27. Christian territorial expansion lacked a firm legal basis in canon law.

28. Pope Innocent IV raised the question, ‘Is it licit to invade the lands that infidels possess, and if it is licit, why is it licit?’ What interested him was the problem of whether or not Christians could legitimately seize land, other than the Holy Land, that the Moslems occupied. Did . . . Christians have a general right to dispossess infidels everywhere?’

29. Innocent acknowledged that the law of nations had supplanted natural law in regulating human interaction, such as trade, conflict, and social hierarchies. Similarly, the prince replaced the father, as the ‘lawful authority in society’ through God’s provenance, manifesting his dominium in the monopoly over justice and sanctioned violence.

IT IS AT THIS JUNCTURE WHERE EUROPEAN PEOPLE, THROUGH POPE INNOCENT IV DECIDED TO SUSPEND THEIR RECOGNITION OF NATURAL IN FAVOR OF WHAT THEY CALLED “THE LAW OF NATIONS.” FROM THIS MOMENT ON, GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS INSTEAD OF EACH INDIVIDUAL, NOW HAD “LAWFUL AUTHORITY” AND MONOPOLY OVER JUSTICE AND SANCTIONED VIOLENCE.

At this point, two different cultures, with two different legal codes, were in conflict - The Balanta and Natural Law vs. the Christian Europeans and their Canon Law/Law of Nations.

30. Innocent delineated a temporal domain that was simultaneously autonomous yet subordinate to the Church.

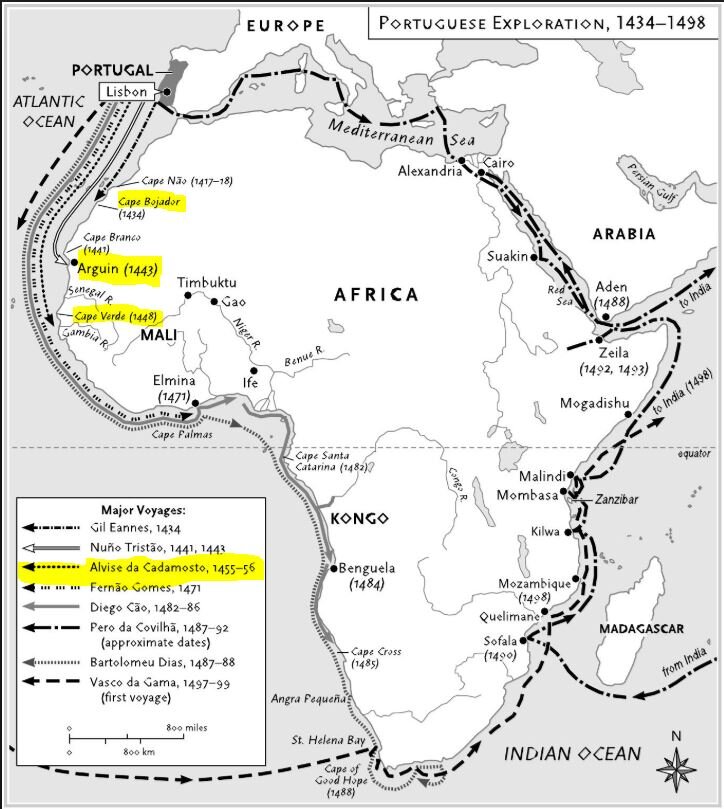

31. Laws of nations pertained to secular matters, a domain in which a significant tendency in the Church, known as ‘dualism,’ showed increasingly less interest. But in spiritual matters, the pope’s authority prevailed, since all humans were of Christ, though not with the Church. ‘As a result,’ the medievalist James Muldoon notes, ‘the pope’s pastoral responsibilities consisted of jurisdiction over two distinct flocks, one consisting of Christians and one comprising everyone else.’ Since the pope’s jurisdiction extended de jure over infidels, he alone could call for a Christian invasion of an infidel’s domain. Even then, however, Innocent maintained that only a violation of natural law could precipitate such an attack. By adhering to the beliefs of their gods, infidels and pagans did not violate natural law. Thus, such beliefs did not provide justification for Christians to simply invade non-Christian polities, dispossess its inhabitants of their territory and freedom, or force them to convert. Innocent IV’s theological contribution resided in the fact that he accorded pagans and infidels dominium and therefore the right to live beyond the state of grace. . . However, The Papal Bull Dum Diversas issued by Pope Nicholas V, June 18, 1452, stated,

“we grant to you full and free power, through the Apostolic authority by this edict, to invade, conquer, fight, subjugate the Saracens and pagans, and other infidels and other enemies of Christ, and wherever established their Kingdoms, Duchies, Royal Palaces, Principalities and other dominions, lands, places, estates, camps and any other possessions, mobile and immobile goods found in all these places and held in whatever name, and held and possessed by the same Saracens, Pagans, infidels, and the enemies of Christ, also realms, duchies, royal palaces, principalities and other dominions, lands, places, estates, camps, possessions of the king or prince or of the kings or princes, and to lead their persons in perpetual servitude, and to apply and appropriate realms, duchies, royal palaces, principalities and other dominions, possessions and goods of this kind to you and your use and your successors the Kings of Portugal.”

PORTUGUESE INVASION OF GUINEA

32. The Portuguese constantly had to contend with theoretical and practical recognition that Guinea did not represent terra nullius (land that is legally deemed to be unoccupied or uninhabited).

33. The "law of nations" was neither natural law, which existed in nature and governed animals as well as humans, nor civil law, which was the body of laws specific to a people.

34. All human beings are born free (liberi) under natural law, but slavery was held to be a practice common to all nations, who might then have specific civil laws pertaining to slaves.

35. In ancient warfare, the victor had the right under the ius gentium to enslave a defeated population; however, if a settlement had been reached through diplomatic negotiations or formal surrender, the people were by custom to be spared violence and enslavement.

36. The ius gentium was not a legal code, and any force it had depended on "reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct."

37. Slavery violated our Balanta ancestors’ Great Belief and egalitarian society. We intentionally did not form centralized state societies because of the inequality it produced. Thus, our Balanta ancestors could not have been a party to any ius gentium, the customary international law held in common among all peoples pertaining to slavery because it violated our customs. Therefore, there could be no “reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct”. Not only was slavery “illegal”, it was unfathomable to our Balanta ancestors.

38. As documented in the official royal account of the Portuguese initial contact with Balanta people, Gomes Eanes de Zurara’s The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea. Commissioned by the House of Avis unfolds, the Portuguese do not act in accordance to existing definitions of conquest.

39. The Portuguese make no effort to contract a treaty so as to acquire a territorial claim to ‘the land of blacks.’

40. The initial Portuguese encounter with the land of Guinea and Balanta people constituted chattel raids that were illegal by natural law, canon law, and the law of nations. Such raids underscore the commercial imperatives.

41. The Church continued to accord infidels and pagans the right to have an existence beyond the state of grace, while consenting that those who had been legitimately enslaved could be reduced to chattel.

42. The Portuguese gradually distinguished ‘Africa’ from ‘Guinea.’ In contrast to the ‘’land of the Moors’, Guinea, ‘the land of the blacks’, represented the more fertile region.

43. Eventually the Portuguese rendered geographical dissimilarities into customary and ultimately juridical distinctions, separating Moors from blackamoors.

44. In 1441, twenty-six years after the conquest of Ceuta, the Portuguese expedition under Antao Goncalves landed near Cabo Blanco in present-day Mauritania. Following a brief skirmish ‘in the land of Guinea’ with a ‘naked man following a camel’, the Portuguese enslaved their first Moor. . . . By their actions, the Portuguese launched the transatlantic slave trade in whose wake the early modern African diaspora emerged and in which the ‘slave’ constituted the charter subject. Through the capture of the “Mooress’, but in particular by marking her as distinct from the Moors on the basis of juridical status and phenotype, the Portuguese introduced a taxonomy that distinguished Moors from blackamoors, infidels from pagans, and Africans from blacks, sovereign from sovereignless subjects, and free persons from slaves. Shortly thereafter, the Portuguese employed this human measure, formulated via a black woman’s body, so as to delineate who could be ‘legitimately’ enslaved.

45. The Portuguese quickly equated status with sovereignty and the lack thereof with the legitimate enslavement of certain individuals. Though the Portuguese captured both Moors and the ‘black Mooress,’ they had already started distinguishing between sovereign ‘Moorish’ subjects and those ‘Moors,’ ‘Negros,’ and ‘black’ that they could legitimately enslave. Zurara observed that the ‘black Mooress,’ unlike the valiant yet vanquished ‘Moor,’ represented the ‘legitimately’ unfree. . . . As the Portuguese encountered more of Guinea’s inhabitants the terms ‘Black Moors’ ‘blacks,’ “Ethiops,’ ‘Guineas,’ and ‘Negroes,’ or the descriptive terms to which a religious signifier was appended such as ‘Moors. . . [who] were Gentiles’ and ‘pagans’ gradually constituted the rootless and sovereignless – and in many cases, simply ‘slaves’.

46. Laws and practices shaping Church-state relations with nonbelievers in Europe set the precedent for Christian interaction with non-Christians in the wider Atlantic world.

CHARTERS

47. A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the British Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but since the 14th century have only been used in place of private acts to grant a right or power to an individual or a body corporate.

48. Charters have been used in Europe since medieval times to grant rights and privileges to towns, boroughs and cities. During the 14th and 15th century the concept of incorporation of a municipality by royal charter evolved.

49. Between the 14th and 19th centuries, royal charters were used to create chartered companies – for-profit ventures with shareholders, used for exploration, trade and colonization. Early charters to such companies often granted trade monopolies, but this power was restricted to parliament from the end of the 17th century. Until the 19th century, royal charters were the only means other than an act of parliament by which a company could be incorporated

CORPORATE IDENTITIES AND NEW FORMS OF PERSONHOOD

50. Beginning in the thirteenth century and in the context of the Reconquista, some Christian lords on the Iberian Peninsula started undermining the corporate bodies of Jews and Saracens by ordering those populations to adhere to Christian legal precepts and Iberian customary laws.

51. By the thirteenth century, when the tide favored Christians, the victorious rulers displayed less willingness to respect Moorish and Jewish corporate institutions and practices. This intransigence flourished at the very moment that Castilian scholars rediscovered Roman civil law, which they codified along with their customary practices in the Siete Partidas. Following this legal transformation, the Christian monarchs continued restricting the judicial autonomy of their Jewish and Moorish subjects. In 1412, this culminated in the most draconian legislation to date when it ‘forbade Jews and Moslems alike to have their own judges. Thenceforth, their cases, civil and criminal, were to be tried before ordinary judges of the districts where they lived. Criminal cases were to be decided according to Christians custom. . . .’

52. By their actions, Portuguese and Spanish Christian rulers contrived new forms of personhood. In a world defined by corporations with their accompanying rights and obligations, Jews and Moors embodied corporate-less beings that Christian authorities compelled to adhere to Christian laws and customary norms thereby forsaking their own legal traditions and customs.

53. By undermining Jewish and Moorish courts, the Christian rulers redefined more than their relations to Jews and Moors. As they dismantled the courts that had once enabled Jews and Moors to reproduce their distinctive juridical status, the Catholic sovereigns actually reconstituted the meaning of being a Jew or a Moor. Standing before Christian courts and officials whose rulings owed much to Christian ethics, the various diasporic populations – Jews, Moors, and Africans - lacked the protective shield of a culturally sanctioned corporate status.

54. The main purpose of the Portuguese crown was always to exploit the Guinea trades to the highest royal advantage, but its methods varied, for different schemes were tried, according to the particular preference of the reigning king.

55. Nevertheless, through all the superficial fluctuations of economic policy, we may discern a constant effort to make profit by the creation of monopolies.

56. Private merchants, the subjects of soverigns who have no legal claim to Guinea, will equip ships to make the traffic in spite of papal prohibitions, Portuguese protests and threats, and the lurking dangers of the Ocean. . . .

57. The events of the war with Castile had shown that, if the Guinea monopoly was to be upheld, steps must be taken to protect it. Moreover, there were signs of unwelcome activity in the ports of Flanders and England, and indications that Florentine, Genoese, English and Flemish merchants wanted to share in the gold trade. These reasons, combined with vague fears of what the future might have in store, drove the Portuguese, immediately after the return of Columbus from his first voyage of discovery to the west, to seek a confirmation of their monopoly. Their efforts were rewarded in 1493-4 by papal bulls and the Treaty of Tordesillas. . . .

58. The two powers ceased, after 1494, to compete in West Africa. Nevertheless, a bilateral treaty was insufficient to deter the governments of France and England from encouraging their mariners to venture in the Guinea Traffic. . . .

59. Fifty years of quiet consolidation in Guinea came to an abrupt end in 1530. . . . Portuguese merchants, thus left alone, seized the opportunity to build up a profitable trade, and Portuguese missionaries undertook the evangelization of many of the negro tribes. . . .

ENGLISH INVASION OF GUINEA

60. Until 1553, the part played by Englishmen in West Africa was negligible.

61. English traders henceforth made regular voyages to Guinea. The later struggles were the outcome of acts of pure aggression, perpetrated by groups of enterprising merchants and sailors in England and in France, against imperial Portugal. Dynamic interlopers assailed a static empire. . . . .

62. Thus, by the law of nations and the Treaty of Tordesillas, French and English activities in Guinea and among the Balanta people were illegal.

63. London merchants and Plymouth sailors now advanced religious arguments, as well as the argument of force, to support their clandestine operations in Guinea. Indeed, their operations ceased to be clandestine when Queen Elizabeth took the crown which Mary had worn so uneasily. They openly attacked the papal division of the world and declared a holy war for the liberation of the seas. . . . The catholic states in Europe were drawn together and their imperial policies coordinated.

64. One of the salient features of this interaction was the association of those in high places with many of the illegal voyages to Guinea. . . . An examination of the personnel of those associated with the English voyages to Guinea reveals many highly placed officials, and demonstrates that the English government was, more than the French, definitely and openly sympathetic towards these enterprises.

65. The men who were interested in Guinea clearly saw that trade, whatever its character, could be greatly facilitated by a permanent station in West Africa. The preeminence of Englishmen among the interlopers in the period from 1559 to 1571 is indicated by the fact that nearly all the contemporary projects of colonization in Guinea were of English origin.

LANCADOS AND AFRICAN COMPLICITY

66. Europeans would have had to do business with the African ruling class through the intermediary of the Lancados. Consequently, commerce on the Upper Guinea Coast settled down into a pattern dominated by the lancados. The main business of the lancados and grumetes was slaving.

67. The Portuguese government’s view of these settlers: they were Godless and would stand in the way of a Portuguese monopoly on trade from the region. Indeed, the government so feared this group that at the start of the sixteenth century it declared trading in Guinea without a license a capital offense. No person ‘irrespective of rank or station, should throw himself with the Negroes, nor under any circumstances, remain with the said Negroes, on pain of death. . . . .By the end of the sixteenth century, lancados were no longer considered outlaws. However, they continued to present problems for Portugal. On the one hand, they served as brokers for Portuguese and Cape Verdean ship captains. On the other hand, they were unconstrained by legislation prohibiting ‘interlopers’ – principally French and British ships – from trading in the region. Feeling no particular loyalty to Portugal, lancados traded with whomever they pleased, seeking the best price for their slaves and goods. . . .

68. The most significant partnership was between the Europeans and the Mandinga, among the latter of whom were the principal agents of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in Upper Guinea. Many of the resident ‘Portuguese’ traders were in fact mulattos of Portuguese and Mandinga extraction. These aspects of the social situation in Upper Guinea pointed to the fact that the majority of captives were exported through the agency of the Mandinga.

69. It seems that while the main purpose of the raids was to obtain captives for sale to Europeans, Mandinga rulers regarded this as a means of disciplining recalcitrant subjects who refused to pay tribute or to recognize Mandinga supremacy. This was the manner in which the issues were posed in the late eighteenth century when the Mandinga ruler of Fogny was exploiting the Banhun and Djola of the Bintang and Casamance. He demanded tribute from them, and attacked when they refused to comply, selling large numbers as slaves.

70. Both the slavers and the slaveowners who dealt with these Africans invariably referred to them collectively as escravos de ley. This name was born of the fiscal arrangement by which the Iberian monarch had a one-third interest in the sale price of these slaves, but it came to mean ‘slaves of the highest quality’.

71. Diversity and unpredictability fueled the wars and encouraged the raids that produced thousands of captives. On this Rio de Sao Domingos [a small tributary of the Cacheu]’ Almada wrote in the late sixteenth century, ‘there are more slaves than in all the rest of Guinea since they take them [from] these nations – Banhuns, Buramos, Cassangas, Jabundos, Falupos, Arriatas and Balantas.’ Each of these groups was located within the ria coastline and close to the frontier of the powerful and expanding interior state of Kaabu. . . . In the closing years of the century, Cacheu replaced Sao Domingos as the most important entrepot on the Rio Cacheu. . . . The town began to attract increasing numbers of lancados in large part because area Papel recognized the advantages of allying themselves with them. Thus, Papel did all they could to make lancados feel welcome and comfortable. . . .

72. About 135 kilometers upriver from Cacheu, Farim was also an important port on the Cacheu. Farim sat at the ria coastline’s edge and attracted a great number of Mandinka merchants, who dubbed the town Tubabodaga, or ‘White Man’s Village.’ There lancados met with Mande-speaking traders, most of whom were from Kaabu. Connections to Mandinka at Farim were crucial to the success of lancado merchants, particularly in the seventeenth century. This was a period of expansion of both the Kaabu empire and the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves taken in Kaabu’s wars were sold to lancados at Farim and then shipped west to Cacheu, where they were put aboard vessels bound for the Cape Verde Islands and points beyond.

73. The allure of European imports also drew the Papel of Bissau into the trade in slaves. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, Papel found guilty of various crimes, especially adultery, were subject to being sold to ship captains. Papel found other ways to profit from the New World’s demand for laborers. In 1605, Barreira said that a Papel chief’s son on Bissau was loath to become Christian ‘because, if he did so, he would have to give up ‘roping them in,’ that is, attacking and enslaving blacks.’ In 1686, Spanish Capuchins described how bands of Papel left the island and raided coastal communities, bringing captives back. ‘Usually,’ a Capuchin said, ‘the Papel depart in their canoes and plunder and pirate men on the shores of the sea and inland.’ Papel slavers explained that ‘they abduct men because the whites buy them.’ . . .

74. The idea of commerce with the Europeans and the acceptance of the European presence did not find a universal and simultaneous welcome. Indeed, some tribes displayed chronic hostility towards the Europeans; The Djolas were in this latter category. . . . Another group, the Balantas, were so hostile that the belief was widespread among the Europeans on the coast that the Balantas killed all white men that they caught.

75. The Europeans always dealt with the kings, chiefs, and nobles of the Upper Guinea Coast. . . . Each resident trader placed himself under the protection of an African ruler; and there was an understanding on mutual rights and obligations. . . .

THE 16TH CENTURY LEGAL REVOLUTION IN ENGLAND

76. Throughout Europe, the 16th century was a period of considerable change in the law. In part a reaction by the learned against the law of the past—which was seen to be too dependent upon ancient Roman models or local Germanic custom—the changes usually took the form of an explicit commitment to improved procedures, above all written rather than oral. One consequence was the increased influence of universities and university-trained lawyers. In England, the old customary law applied by the central courts at Westminster was too firmly entrenched to be lightly overthrown, but even here the development of written pleadings and new, speedier remedies had a transforming effect. The aforementioned prerogative, or conciliar, courts, together with the Court of Chancery, competed with common-law courts for jurisdiction over the same cases and followed a written procedure modeled after that still being used on the Continent. Roman law and canon law were taught at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, which awarded doctorates to the practitioners in these courts.

77. The Tudors made use of proclamations by the king to invoke emergency measures, to establish detailed regulations, especially on economic matters, and to grant royal charters to trading companies. Parliament passed laws of a political nature, such as those enforcing the king’s supremacy over the newly established Church of England. Statutes also regulated imports and exports, controlled farming, and defined what was unfair competition. A law of 1562–63 regulated apprenticeships and provided for annual wage fixing by magistrates in accordance with the cost of living. There were other important statutory innovations during these years. The Statute of Monopolies of 1623 confirmed that monopolies were contrary to common law but made exceptions for patentable inventions, and a statute of 1601 became the basis of the privileges enjoyed by charitable trusts.

78. In 1615 King James I declared that the chancery was to retain its traditional superiority over the common-law courts, but only in areas in which its authority was well recognized. If the applicability of equity was in doubt, the common law was to be followed.

79. Of extraordinary influence in the development of common law and in its dissemination to other parts of the world was the most famous of English jurists, Sir William Blackstone. He was born in 1723, entered the bar in 1746, and in 1758 became the first person to lecture on English law at an English university. His most influential work, the Commentaries on the Laws of England, was published between 1765 and 1769 and consisted of four books: Of the Rights of Persons dealt with family and public law; Of the Rights of Things gave a brilliant outline of real-property law; Of Private Wrongs covered civil liability, courts, and procedure; and Of Public Wrongs was an excellent study of criminal law. Lawyers and laymen alike came to regard it as an authoritative exposition of the law. In the following century, the fame of Blackstone was even greater in the United States than in his native land. After the American Declaration of Independence (1776), the Commentaries became the chief source of knowledge of English law in the New World.

EARLY RECORD OF ENCOUNTERS IN BALANTALAND

80. 1594 Earliest account of the Balantas (by name) in written records, Andre Alvares Almada, Trato breve dos rios de Guine, trans. P.E.H. Hair - “The Creek of the Balantas penetrates inland at the furthest point of the land of the Buramos [Brame]. The Balantas are fairly savage blacks.”

81. 1615, Manuel Alvares commented, ‘They [Balantas] have no principle king. Whoever has more power is king, and every quarter of a league there are many of this kind.’

82. 1618 English Company of Adventurers is chartered for trade in gold and slaves. The company builds a fort on James Island in the River Gambia to rival the Portuguese in Casamance and Guinea.

83. 1619 Slave traders allowed to pay crown tax directly at Cacheu and bypass the slave tax paid in the Cape Verde Islands.

84. 1627, Alonso de Sandoval wrote that ‘Balanta were ‘a cruel people, [a] race without a king.’

85. 1672 Formation of the English Royal African Company

86. 1676 Formation of Companhia de Cacheu, Rios e Comercio da Guine to provide taxes and slaves for the Portuguese Crown, and approve the capitao-mor, who is Antonio de Barros Bezerra and the main shareholder of the company, which failed in 1682. The individuals from Santiago and Cacheu who formed it were to reinforce Cacheu’s stockade and man it with soldiers. Duties collected on local trade and a portion of tax revenues on slave exports were to accrue to the company. . . . In 1690, a second Company of Cacheu was incorporated, and the Portuguese government negotiated an agreement to supply slaves to Spanish America. . . .

87. 1684 Francisco de Lemos Coelho says that much of the territory of the Balanta ‘has not been navigated, nor does it have kings of consideration.’

88. 1750’s Merchants of Grao Para and Maranhao (Brazil) call for an increase in its slave imports from Guinea for sugar, cotton, rice and cacao production and are authorized by the Crown to form a slave trading and commercial company.

89. 1776 The American Revolutionary War begins, and Americans increase imports of rice and cotton from Maranhao, which requires more slaves from Guinea. Slaves are generated as the revivalist Fula Muslims complete the formation of the Imamate of Futa Toro and bring an end to the Denianke lineage in Futa Toro.

90. At no time was the concentration of wealth in the hands of members of the b’alante b’ndang (or any other group) ever so pronounced that it led to the crystallization of an elite class. Therefore, it was impossible for outside forces to gain influence over Balanta culture without direct conquest and the commitment of military resources.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE AMERICAN COLONIES AND “LEGAL’ JURISDICTIONS

https://study.com/academy/lesson/colonial-government-forms-charter-proprietary-royal-colonies.html

91. Colonial governments assumed one of three forms: charter, proprietary, or royal. Charter colonies were governed by joint stock companies, which received charters from the king and enjoyed quite a bit of self-government. Proprietary colonies were granted by the king to a proprietor or head of a proprietary family, who owned the colony by title and governed it as he saw fit. Royal colonies were controlled by the king through his representative, the royal governor.

92. Charter colonies (Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts) were governed by corporations called joint stock companies. Individuals hoping to make a profit purchased stock in these companies to finance colonization. When a company had enough money, it applied to the king for a charter, which is an agreement between the monarch and a colony that lays out the rights and responsibilities of both parties. If the king granted a charter, the company recruited colonists, set up a government, and founded a colony. Charter colonies often enjoyed a higher level of self-government than other colonies. The joint stock company-controlled land distribution and took an active role in colonial government. Colonists tended to prefer this form of colonial government because of the freedom it allowed, but only Connecticut and Rhode Island were still charter colonies by the time of the American Revolution. Massachusetts had also been a charter colony for many years until the king decided he wanted more control and revoked the charter.

93. Proprietary colonies (Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware) were granted by the king directly to an individual or family. The proprietor or head of the proprietary family governed the colony as he saw fit. Technically, he had to report to the king, but in practice, he usually had quite a bit of independence. One important proprietor was William Penn. The King of England at the time, Charles II, granted Penn the land that Penn would use to found the colony of Pennsylvania. The proprietor, who officially owned his colony by title, could make laws, grant land, collect rents and fees, establish towns, create legislative bodies and courts, and authorize churches. Colonists turned to the proprietor for leadership and justice and were usually satisfied with the results.

94. Royal colonies (Virginia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, New Hampshire, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) were directly controlled by the king, who was represented by a royal governor. Through the governor and his council, the king controlled land grants and sales, taxation, and the law. Colonists could elect their own assemblies to pass local ordinances and laws, but the royal governor had complete veto power over these assemblies and their decisions. He could even dissolve them if he chose to. Royal colonies existed for the benefit of the king, who, of course, preferred this style of colonial government above all others. Colonists, on the other hand, often became frustrated with the royal colony system and rebelled at its tight control. At the time of the American Revolution, royal colonies included Virginia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, New Hampshire, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

PLYMOUTH COLONY

95. The first settlement in New England was Plymouth Colony. It was chartered by a group of Puritan separatists initially known as the Brownist Emigration and commonly referred to as the Pilgrims who arrived via the Mayflower in 1620 with 102 passengers. After a rough start, they were happy in Plymouth. They could practice their own form of Christianity without bothering anyone else, and they had plenty of food thanks to their friendly Wampanoag neighbors.

96. The Mayflower was originally bound for the Colony of Virginia, financed by the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London, a trading company founded in the City of London in the early 15th century. It brought together leading merchants in a regulated company in the nature of a guild. In the early seventeenth century, similar groups of investors were formed to develop overseas trade and colonies in the New World: the Virginia Company (which later split into the London Company settling Jamestown and the Chesapeake Bay area, and the Plymouth Company, an English joint-stock company founded in 1606 by James I of England as a company of Knights, merchants, adventurers, and planters of the cities of Bristol, Exeter and Plymouth with the purpose of establishing settlements on the coast of North America.

The company received its royal charter from King Henry IV in 1407, but its roots may go back to the Fraternity of St. Thomas of Canterbury. It claimed to have liberties existing as early as 1216. The Duke of Brabant granted privileges and in return promised no fees to trading merchants. The company was chiefly chartered to the English merchants at Antwerp in 1305. This body may have included the Staplers, who exported raw wool, as well as the Merchant Adventurers. Henry IV's charter was in favor of the English merchants dwelling in Holland, Zeeland, Brabant, and Flanders. Other groups of merchants traded to different parts of northern Europe, including merchants dwelling in Prussia, Scania, the Sound, and the Hanseatic League (whose election of a governor was approved by Richard II of England in 1391), and the English Merchants in Norway, Sweden and Denmark (who received a charter in 1408).

Under the charter of 1564, the company's court consisted of a governor (elected annually by members beyond the seas), his deputies, and 24 Assistants. Admission was by patrimony (being the son of a merchant who was free of the company at the time of the son's birth), service (apprenticeship to a member), redemption (purchase) or 'free gift'. By the time of the accession of James I in 1603, there were at least 200 members. They gradually increased the fees for admission.

Council for New England

The Council for New England was the name of a 17th-century English joint stock company that was granted a royal charter to found colonial settlements along the coast of North America. The Council was established in November of 1620 and was disbanded (although with no apparent changes in land titles) in 1635. It provided for the establishment of the Plymouth Colony, the State of New Hampshire, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the New Haven Colony, and the eventual State of Maine. It was largely the creation of Sir Ferdinand Gorges.

Some of the persons involved had previously received a charter in 1606 as the Plymouth Company and had founded the short-lived Popham Colony within the territory of northern Virginia (actually in present-day Maine in the United States). The company had fallen into disuse following the abandonment of the 1607 colony. The Council was re-established after, with support from Gorges, (1) Captain John Smith had completed a thorough survey of the Atlantic side of New England (and named it such), (2) Richard Vines over-wintered in 1616, off the Maine coast and discovered that a plague was decimating Native Americans and (3) a friendly English speaking local Native American had been placed in the most likely colonization spot.

In the new 1620 charter granted by James I, the company was given rights of settlement in the area now designated as New England, which was the land previously part of the Virginia Colony north of the 40th parallel, and extending to the 48th parallel. In 1622 the Plymouth Council issued a land grant to John Mason which ultimately evolved into the Province of New Hampshire.

97. Storms forced the Mayflower to anchor at the hook of Cape Cod in Massachusetts, instead of Virginia, as it was unwise to continue with provisions running short. This inspired some of the non-Puritan passengers (whom the Puritans referred to as "Strangers") to proclaim that they "would use their own liberty; for none had power to command them" since they would not be settling in the agreed-upon Virginia territory. To prevent this, the Pilgrims determined to establish their own government, while still affirming their allegiance to the Crown of England. Thus, the Mayflower Compact was based simultaneously upon a majoritarian model and the settlers' allegiance to the king. It was in essence a social contract in which the settlers consented to follow the community's rules and regulations for the sake of order and survival:

“IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. “

MASSACHUESETTS BAY COLONY

98. But just a few years later a second Northeast colony was chartered, overwhelming Plymouth in 1628. Soon, about 400 strict, religious Puritans arrived. They were called Puritans because they felt it was their God-given duty to purify the church from the influences of Roman Catholicism. In Europe, the Puritans were actually a huge group with a lot of political influence, but a new English king was aggressively persecuting them, leading to civil war. Within a decade, 20,000 Puritans immigrated to America. Massachusetts Bay Colony had arrived. In 1630, the first wave of Puritans met up with survivors from an abandoned colony and renamed the little settlement Salem and its Governor was John Winthrop.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded by the owners of the Massachusetts Bay Company, which included investors in the failed Dorchester Company which had established a short-lived settlement on Cape Ann in 1623. The colony began in 1628 and was the company's second attempt at colonization. It was successful, with about 20,000 people migrating to New England in the 1630s. The population was strongly Puritan, and its governance was dominated by a small group of leaders who were strongly influenced by Puritan teachings. Its governors were elected, and the electorate were limited to freemen who had been examined for their religious views and formally admitted to the local church.

The colony was not a democracy, it was a theocracy - for the purpose of serving God and increasing His kingdom, not to let people live however they saw fit. Any challenge to the Church's authority undermined the colony's mission and all that they had worked so hard to accomplish. Any person who challenged the strict practices of their faith was literally thrown out of the colony. This would have been a death sentence to individuals in the early years.

COLONY OF RHODE ISLAND

99. Roger Williams was one of these unlucky Puritans. He didn't agree with the practice of legally punishing citizens for breaking religious rules, and as a preacher, he taught that the land of New England rightfully belonged to the Natives, not the King or colony. In 1635, Roger Williams was convicted of teaching diverse, new and dangerous opinions. He was ordered to leave Massachusetts before the spring. But since Williams wouldn't keep his opinions to himself throughout the winter, the leaders of Salem decided to arrest him immediately and send him to England, where he was also likely to face imprisonment because of the Civil War. Instead, he fled into the wilderness alone. He was discovered in the snow, nearly frozen, by some Wampanoag. They nursed him back to health, and Chief Massasoit even gave him some land. Unfortunately, it was still inside the colonial charter, so Williams moved on yet again. This time, he purchased land from the Narragansett Indians and established a settlement he called Providence in 1636. As you might expect, his colony guaranteed wide personal and religious freedom. Roger Williams was joined by his family and twelve followers.

Two years later, a Massachusetts woman named Anne Hutchinson got in trouble with the church in Boston. Unusually well-educated by her father, who was a minister, Hutchinson started hosting a discussion group for women in her home to talk about the sermons they had heard in church on Sunday. But because she sometimes criticized the preachers and sometimes taught men, she came under scrutiny. At her trial and sentencing, officials told her, 'You have stepped out of your place, you have rather been a husband than a wife, a preacher than a hearer … you are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society.' Even before her trial ended, Anne Hutchinson's family and several close friends signed a compact and agreed to leave Massachusetts. Roger Williams convinced them to come to Narragansett Bay, where they also purchased land and founded the town of Portsmouth. Hutchinson joined them after her sentencing in 1638.

A few years later, Roger Williams successfully combined Portsmouth, Providence and some other small communities into the colony of Rhode Island.

CONNECTICUT AND NEW HAMPSHIRE COLONIES

100. Back in 1636, a preacher named Thomas Hooker led some Puritans out of Massachusetts because he disagreed with how the colony limited voting rights. Hooker and his followers founded the colony of Connecticut. The following year, another group of Puritans left Massachusetts because they thought it wasn't being strict enough! Their colony, New Haven, and some other settlements were soon absorbed into Connecticut. The last of the New England colonies to be formed was New Hampshire. It was chartered by the King directly in 1679 simply because Massachusetts was growing too large.

101. The northern and southern American colonies had plenty of differences, but one thing they all pretty much had in common was ancestry. Virginia, Massachusetts, Maryland, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire, the Carolinas and Georgia were all founded by Englishmen, settled by people of English descent and remained under English control throughout the colonial period. This could not be said of the middle colonies (New York, Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania).

What led to the use of slavery and the creation of different colonies?

102. Virginia was started by a group of men in 1607 who wanted to get rich quick. Even through the 1620s, ¾ of Virginia's population was still male, and the goal of the colony was still money. This was achieved through large farms called plantations that planted cash crops - namely, tobacco.

But tobacco requires a lot of manpower, and Jamestown had a population problem. The birth rate was low, and the death rate was high. England had the opposite problem: there were too many people. There was not enough work, no chance to own land and no opportunity for the poor. Even some rich kids faced this dilemma, because English inheritance laws required that all property be passed to the oldest son - and England was full. The younger sons of the noblemen had plenty of money, but no land to build their own estates.

An English politician named Edwin Sandys proposed a solution called the headright system. Anyone who paid for the trip to Virginia received 50 acres. So the rich guys paid for poor people to come with them as servants. These servants were indentured to the landowner, typically for seven years. The gentlemen got the land and free workers for seven years. The lucky 15% of servants who survived their indenture had almost nothing. As a result, Sandys' system created class divisions between the 'haves' and the 'have-nots.'

A deep social divide quickly overtook Virginia. Wealthy planters owned all of the best land and controlled all of society. Though the House of Burgesses was an elected government, only landowning men could vote.

Bacon's Rebellion

103. Many former indentured servants - both black and white - headed out onto the western frontier where they fought constantly with the natives. In Jamestown, the leaders ignored their pleas for help. So they took matters into their own hands. A frontier planter named Nathaniel Bacon organized a militia to take revenge on the Indians. When the governor ordered him to stop, the frontiersmen felt like the upper class had absolutely no regard for them. Bacon's army turned into a rebellion against colonial leadership. In 1676, the frontier militia marched into Jamestown, trashed the governor's home and burned the capitol. Nathaniel Bacon died of dysentery, so the rebellion fell apart. But it wasn't without consequence. To weaken the power of the lower class, the House of Burgesses granted all free white men the right to vote, dividing society along color lines. Bacon's Rebellion also helped turn planters away from indentured servitude and towards slavery.

MARYLAND

104. Back in 1632, two communities dominated America: the money-hungry colony of Virginia and the Puritan refuge of Massachusetts. Civil war in England had driven thousands of Puritans to the northern colony. This same war also led a man named Cecilius or Cecil Calvert (whose title was Lord Baltimore) to start a new American colony for Catholics. He called the colony Maryland, and it resembled Virginia in many ways, including tobacco plantations, indentured servants and slave labor and high mortality. A settler in Maryland lived ten years less than someone in New England. Despite Calvert's plan, Maryland had a Protestant majority. To protect the Catholics, he approved the Act of Religious Toleration in 1649, guaranteeing political rights to anyone practicing any form of Christianity. But that same year, the king of England was beheaded and Puritans took over the English government. Within a few years, they took over Maryland and overturned that law.

THE CAROLINAS

105. The Puritan government of England lasted just 11 years. The monarchy was restored and the newly crowned King Charles II decided to reward eight of his supporters by giving them a colony in 1663. The eight owners (called proprietors) named it Carolina in his honor. Like most of the American colonies, Carolina was already inhabited, but not just by Native Americans. Some former indentured servants from Virginia had migrated into the northern part of the land at least ten years before the charter was granted. The southern part was inhabited by poor farmers who had been run off of the island colony of Barbados by wealthy planters. Their crops wouldn't grow in America, but they figured out that hogs thrived with almost no overhead cost.

In 1670, a shipload of rich men also arrived from Barbados. They came for the same reason that rich, young men had gone to Virginia: there was just no land left for them on the island. They founded the Port of Charlestown and sold pork to Barbados in exchange for slaves.

Soon, Carolina's economy was transformed by the introduction of rice as a cash crop, but growing it requires specialized knowledge. When planters realized that slaves imported directly from West Africa were already skilled in growing rice, the scramble for land - and the laborers who knew how to work it - was on. By 1708, Africans became the majority of the population. The more money slaves made for their owners, the more the Southern elite were committed to slavery and its permanence.

By contrast, North Carolina didn't have any cash crops. But even if it did, it would've had difficulty exporting anything without a deep water port and only one river that flowed directly into the ocean. So the region attracted very few colonists from overseas. A few Welsh and Scottish immigrants settled up the Cape Fear River, but most of the northern settlers were poor farmers from other areas in search of fertile land. With greater diversity, no exports and no cash crops, North Carolina was much less committed to slavery than South Carolina. The two regions split officially in 1729.

GEORGIA

106. Slaves in South Carolina learned that if they could survive the dangerous journey through the swamps, Florida promised them their freedom. Thousands of slaves attempted to escape. But Carolina also had another problem: the Spanish in Florida kept attacking them. The utopian vision of a British gentleman intervened to solve both problems. James Oglethorpe believed that even the worst people in society could succeed, given the same opportunity. So he asked the King for a charter to settle a colony of people from debtors' prison. In one stroke, the King was able to buffer South Carolina from Spanish attack and create an obstacle for escaping slaves. In 1733, more than a century after Virginia was established, the colony of Georgia was settled.

Oglethorpe intended for Georgia to be a utopia of hard work and social equality, so he outlawed slavery and large landholdings. As a result of these restrictions (and because England wouldn't let its debtors out of prison), Georgia attracted very few settlers, and those who did come complained constantly about their situation. Colonists started moving to South Carolina, so within two decades, Oglethorpe lifted the restrictions, and his utopia turned into a society that looked very much like South Carolina with a plantation economy based on rice.

LEGAL JURISDICTION OF THE AMERICAN COLONIES

General Charters

· 1578 - Letters Patent to Sir Humfrey Gylberte June 11

· 1584 - Charter to Sir Walter Raleigh; March 25

· 1619/20 - Petition for a Charter of New England by the Northern Company of Adventurers; March 3

· 1621 - Charter of the Dutch West India Company; June 3

· 1629 - Sir Robert Heath's Patent 5 Charles 1st; October, 30

· 1634 - Royal Commission for Regulating Plantations; April 28

· 1635 - Declaration for Resignation of the Charter by the Council for New England; April 25

· 1635 - Confirmation of the Grant from the Council for New England to Captain John Mason

· 1637 - Commission to Sir Ferdinando Gorges as Governor of New England by Charles ; July 23

Connecticut

· 1639 - Fundamental Orders; January 14

· 1639 - Fundamental Agreement, or Original Constitution of the Colony of New Haven, June 4

· 1643 - Government of New Haven Colony

· 1662 - Charter of Connecticut

Delaware

· 1776 - Constitution of Delaware

Georgia

· 1777 - Constitution of Georgia; February 5

Maine

· 1639 - Grant of the Province of Maine

· 1664 - Grant of the Province of Maine

· 1674 - Grant of the Province of Maine

Maryland

· 1776 - Constitution of Maryland; November 11

· Amendments to the Maryland Constitution of 1776

Massachusetts

· 1620 - The Charter of New England

· 1620 - Agreement Between the Settlers at New Plymouth

· 1629 - Charter of the Colony of New Plymouth Granted to William Bradford and His Associates

· 1629 - The Charter of Massachusetts Bay

· 1635 - The Act of Surrender of the Great Charter of New England to His Majesty

· 1640 - William Bradford, &c. Surrender of the Patent of Plymouth Colony to the Freeman, March 2D

· 1688 - Commission of Sir Edmund Andros for the Dominion of New England. April 7

· 1691 - The Charter of Massachusetts Bay. October 7

· 1725 - Explanatory Charter of Massachusetts Bay - August 26

New Hampshire

· 1629 - Grant of Hampshire to Capt. John Mason, 7th of Novemr.

· 1635 - Grant of the Province of New Hampshire to John Wollaston, Esq.,

· 1635 - Grant of the Province of New Hampshire From Mr. Wollaston to Mr. Mason, 11th June

· 1635 - Grant of the Province of New Hampshire to Mr. Mason, 22 April , By the Name of Masonia

· 1635 - Grant of the Province of New Hampshire to Mr. Mason, 22 Apr., By the Name of New Hampshire

· 1639 - Agreement of the Settlers at Exeter in New Hampshire

· 1641 - The Combinations of the Inhabitants Upon the Piscataqua River for Government

· 1680 - Commission of John Cutt

· 1776 - Constitution of New Hampshire

New Jersey

· 1664 - The Duke of York's Release to John Ford Berkeley, and Sir George Carteret, 24th of June

· 1674 - His Royal Highness's Grant to the Lords Proprietors, Sir George Carteret, 29th July

· 1676 - The Charter or Fundamental Laws, of West New Jersey, Agreed Upon

· 1676 - Quintipartite Deed of Revision, Between E. and W Jersey: July 1st

· 1681 - Province of West New-Jersey, in America, The 25th of the Ninth Month Called November

· 1682 - Duke of York's Confirmation to the 24 Proprietors: 14th of March

· 1683 - The Fundamental Constitutions for the Province of East New Jersey in America

· 1683 - The King's Letter Recognizing the Proprietors' Right to the Soil and Government

· 1709 - The Queen's Acceptance of the Surrender of Government; April 17

· 1712 - Charles II's Grant of New England to the Duke of York, 1676 - Exemplified by Queen Anne

· 1776 - Constitution of New Jersey

New York

· 1626 - Notification of the Purchase of Manhattan by the Dutch; November 5

· 1777 - The Constitution of New York : April 20

North Carolina

· 1663 - Charter of Carolina : March 24

· 1663 - A Declaration and Proposals of the Lord Proprietor of Carolina, Aug. 25-Sept. 4

· 1665 - Concessions and Agreements of the Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina

· 1665 - Charter of Carolina; June 30

· 1669 - The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina : March 1

· 1775 - The Mecklenburgh Resolutions : May 20

· 1776 - Constitution of North Carolina : December 18

Pennsylvania

· 1681 - Charter for the Province of Pennsylvania : February 28

· 1681 - Concessions to the Province of Pennsylvania - July 11,

· 1682 - Penn's Charter of Libertie - April 25

· 1682 - Frame of Government of Pennsylvania - May 5

· 1683 - Frame of Government of Pennsylvania - February 2

· 1696 - Frame of Government of Pennsylvania

· 1776 - Constitution of Pennsylvania - September 28

Rhode Island

· 1640 - Plantation Agreement at Providence August 27 - September 6

· 1641 - Government of Rhode Island-March 16-19

· 1643 - Patent for Providence Plantations - March 14

· 1663 - Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations - July 15

South Carolina

· 1776 - Constitution of South Carolina - March 26

· 1778 - Constitution of South Carolina - March 19

Vermont

· 1777 - Constitution of Vermont - July 8

· 1786 - Constitution of Vermont - July 4

· 1791 - Admission of the State of Vermont - February 18

Virginia

· 1606 - The First Charter of Virginia; April 10

· 1609 - The Second Charter of Virginia; May 23

· 1611 - The Third Charter of Virginia; March 12

· 1621 - Ordinances for Virginia; July 24-August 3

Note: Ecclesiastical jurisdiction in its primary sense does not signify jurisdiction over ecclesiastics ("church leadership"), but jurisdiction exercised by church leaders over other leaders and over the laity.

Jurisdiction is a word borrowed from the legal system which has acquired a wide extension in theology, wherein, for example, it is frequently used in contradistinction to order, to express the right to administer sacraments as something added onto the power to celebrate them. So it is used to express the territorial or other limits of ecclesiastical, executive or legislative authority. Here it is used as the authority by which judicial officers investigate and decide cases under Canon law.

Such authority in the minds of lay Roman lawyers who first used this word jurisdiction was essentially temporal in its origin and in its sphere. The Christian Church transferred the notion to the spiritual domain as part of the general idea of a Kingdom of God focusing on the spiritual side of man upon earth.

It was viewed as also ordained of God, who had dominion over his temporal estate. As the Church in the earliest ages had executive and legislative power in its own spiritual sphere, so also it had judicial officers, investigating and deciding cases. Before its union with the State, its power in this direction, as in others, was merely over the spirits of men. Coercive temporal authority over their bodies or estates could only be given by concession from the temporal ruler. Moreover, even spiritual authority over members of the Church, i.e. baptized persons, could not be exclusively claimed as a right by the Church tribunals, if the subject matter of the cause were purely temporal.

It is customary to speak of a threefold office of the Church: the office of teaching (prophetic office), the priestly office and the pastoral office (governing office), and therefore of the threefold authority of the Church: the teaching authority, ministerial authority and ruling authority. Since the teaching of the Church is authoritative, the teaching authority is traditionally included in the ruling authority; then only the ministerial authority and the ruling authority are distinguished.

By ministerial authority, which is conferred by an act of consecration, is meant the inward, and because of its indelible character permanent, capacity to perform acts by which Divine grace is transmitted. By ruling authority, which is conferred by the Church (missio canonica, canonical mission), is understood the authority to guide and rule the Church of God. Jurisdiction, insofar as it covers the relations of man to God, is called jurisdiction of the internal forum or jurisdiction of the forum of Heaven (jurisdictio poli). (See Ecclesiastical Forum); this again is either sacramental or penitential, so far as it is used in the Sacrament of Penance, or extra-sacramental, e.g. in granting dispensations from private vows. Jurisdiction, insofar as it regulates external ecclesiastical relations, is called jurisdiction of the external forum, or briefly jurisdictio fori. This jurisdiction, the actual power of ruling is legislative, judicial or coactive. Jurisdiction can be possessed in varying degrees. It can also be held either for both fora, or for the internal forum only, e.g. by the parish priest.

Jurisdiction can be further sub-divided into ordinary, quasi-ordinary and delegated jurisdiction. Ordinary jurisdiction is that which is permanently bound, by Divine law or human law, with a permanent ecclesiastical office. Its possessor is called an ordinary judge. By Divine law the pope has such ordinary jurisdiction for the entire Church and a bishop for his diocese. By human law this jurisdiction is possessed by the cardinals, officials of the Roman Curia and the congregations of cardinals, the patriarchs, primates, metropolitans, archbishops, the praelati nullius and prelates with quasi-episcopal jurisdiction, the chapters of orders or the superior generals of orders, cathedral chapters in reference to their own affairs, the archdiaconate in the Middle Ages, and parish priests in the internal forum.