Excerpts from:

From the Margins of the State to the Presidential Palace: The Balanta Case in Guinea-Bissau

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 October 2013

“Balanta farmers of Guinea Bissau are often regarded by neighboring communities as ‘backward’ and as a people who have refused modern life-worlds. Despite the fact that these farmers played a very important role in the making of Guinea Bissau, they were progressively removed from power after independence. However, they also developed original forms of contesting-marginality. . .

Balanta suffered an abrupt transformation with the advent of the slave trade but were capable of finding a life-world in the mangroves farming mangrove-swamp rice. . . With respect to the Balanta, the fact that some of the most important ceremonies in their social life (male initiations and marriages) are accompanied by millet or sorghum divination rituals reinforces the idea . . . that they previously were upland farmers whose main crops were millet, sorghum and yams, rather than rice (the crop central in their cultural identity today). . . .

Once in the mangrove frontier, the Balanta became the kind of ‘deep rural’ people Murray Last (1980) once described as following an ‘isolationist rationale’ in their marginalized societies. They resisted Islamization first and then the Westernization and (Christianization) brought by the Portuguese.rule. Unlike other groups who learned to see some positive aspect in either Muslim, Christian or Western impositions (such as the Nalu, who converted to Islam, sent their children to school, changed their styles of dress, etc.), the Balanta viewed them mostly as negative. They adopted a strategy of ‘conservative change’ (Last 1980), consciously developing only those elements that could strengthen their own livelihoods. . . . This isolationist rationale produced among their neighbors the image of the Balanta as a ‘backward’ and warlike people. Yet in as much as this image was also the product of their own agency, we might view it as ‘protective camouflage,’ one more element of their ‘deep rural’ identity. . . .

During the liberation war (1963-74) and in the post-colony, however, young Balanta ‘aspirations to ‘likeness’’ - with local standards of progress and modernity began to grow and to turn the ‘isolationist rationale’ into a burden. . . . that gave rise to several schismatic processes. . . .

Throughout the whole colonial period which ended in 1974, the Balanta preferred to live off rice (both as subsistence and a cash crop with which they paid the hut tax and bought cattle), choosing not to go to school, privileging the use of their own language (even today many of them do not speak the country’s lingua franca, Kriol) and their fearsome initiation practices, and relying for their survival on physical strength, hard work, and last but not least, theft (mainly of cattle).

Balanta B’urassa History and Genealogy Society in America Vice President Sansau Tchimna visiting a rice field in Bairo Militar in 2021

While these practices probably had as many benefits in colonial times, they eventually created a stereotype of ‘backwardness’ and of the Balanta as the ‘ethnic other’ of the post colony. However, . . . the Balanta were skilled innovators in their agricultural practices and fiercely determined to ‘develop their existing ‘niche’, not to transform it’ (Last 1980). In fact, Balanta migration to the south was triggered by the search for new rice fields (particularly during the famine caused by dry years) along with the need to escape colonial forced labor (which at first did not affect the southern part of the colony). . . .

According to Chabal (1983:69), Balanta farmers became involved in the anti-colonial guerrilla war (1963-74) more quickly than any other group. Amilcar Cabral (1974:86,87), the leader of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), explained the Balanta’s adherence to the anti-colonial struggle as a product of their decentralized and egalitarian social organization; he contrasted their attitude to those of the Fulbe, a state-based group that formed an alliance with the colonial power. Cunningham (cited in Chabal 1983:69,79) argued not only that the Balanta were highly exploited by land concessionaries (pointeiros), but also that their organization into age groups - some of them specifically trained for fighting - facilitated their integration into a guerrilla war. . . .

Local explanations are also multiple, but they all corroborate the idea that the Balanta were particularly oppressed in colonial times, more so than any other groups. Consider the following statement made by a Nalu:

“In colonial days, the Balanta were those who suffered the most with slaps, and lashing because they refused to dress, wash or work on the roads. The cipaios [administrative ‘policemen’] beat them and slept with their wives, something they never did to Muslims. In the pontas [land concessions] they stayed like captives and traders would also trick them, because they [Balanta] did not know money. (Interview with Aladji S. C., February 8, 2004). . . .”

In interviews conducted in 2004 with thirty-nine Balanta elders of different Cubucare villages, the most salient feature of colonial oppression was forced labor in the building of roads, during which not even food was provided, and the use of physical violence by colonial officers. . . .

When the anti-colonial guerrilla war began, Southern Balanta were particularly numerous in its fronts. According to several interviewees, the first Balanta to join the PAIGC were among the biggest thieves, because they were brave, they could walk in the night without being noticed, and they knew how to keep secrets. When the war began, these new commanders found opportunities for revenge against elders who previously had detained or tried them, accusing the elders of collaborating with the colonial power and in many cases having them executed. Furthermore, both commanders and villagers began to interpret the multiple deaths of young Balanta soldiers in terms of witchcraft committed by village elders. With the support of siks (spiritual practitioners), some commanders organized fiery-yaab groups. Accusations of witchcraft got out of control and many people were beaten to death, shot, or even burnt (see Jong 1987:78). The situation was so grave that one of the objectives of the first congress of the PAIGC, held in Cassaca (1963), was to stop accusations of witchcraft among the Balanta and to punish the main commanders responsible, some of whom were executed (see Chabal 1983:72,73,78,79),

Although this initial revolt against the elders was suppressed, the liberation war itself resulted in a considerable empowerment of Balanta young men.

Amilcar Cabral tried to fight what he considered ‘backwardness’ with political teaching and also by sending people to school (children as well as soldiers).

The war had also eroded social organization. For more than a decade no male initiation was conducted, which resulted in the relaxing of the rules controlling marriage and the creation of new households by young men. . . .

After independence, despite their participation in the war, the Balanta felt marginalized by the PAIGC. The politics of the new government led to stagnation in agriculture and the impoverishment of farmers. The fixing of rice price support until 1986, and the compulsory direct exchange between rice and other goods in state stores, affected Balanta farmers (mainly the southern ones, exclusively dependent on rice farming) much more than any other groups in Guinea Bissau. During the war, much of the paddy field infrastructure was destroyed, either by bombs or by lack of maintenance. . . .

In the midst of these dire conditions rumors spread in 1984 about a woman named Maria Ntombikte who was possessed by N’hala (Balanta’s High God) and had started to prophesize important changes in Balanta social life. Very quickly she gathered hundreds of followers. . . . Both the movement and its followers have been known ever since as ‘Kiyang-yang’ (sing. Yang-yang or ‘shadow’). According to the historian of religion Inger Callewaert, the Kiyang-yang movement represented the ‘birth of religion’ among the Balanta, meaning that until that moment they did not have a ‘religion’ in the sense of an ‘autonomous realm’ and institution (2000:173). . . .

[Here is how the movement is described by the journal Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry:

“In the autumn of 1984, a wave of rumors spread across southern Guinea Bissau about “mad” Balanta women who were unable to conceive or whose children had died. They tried to find relief from a woman who received messages from the Balanta god Nhaala, telling her to cure other people, pointing out medicinal herbs and commanding her to put an end to witchcraft in the country. What started as a healing cult for individuals developed into a movement of young people, especially women, that shook Balanta society to its foundations and had national repercussions. At the time, the first author worked as a psychiatrist in the country (from 1981 till 1985).1 The state authorities sent him to the south to treat the “crazy women.” He transformed this order into ethnographic research and, subsequently, tried to convince the government not to medicalize a collective dissociative phenomenon that, in his opinion, was caused by massive traumatic stress. To a large extent, the stress was caused by 22 years of liberation struggle that had ended in 1974. It had escalated into bombardments with napalm and the widespread use of landmines, resulting in large numbers of casualties, amputations and refugees. Part of the population chose to live in the liberated areas, whereas the Portuguese copied the Algerian and Indochinese policy of “protected villages,” obliging the local population to function as a shield against attacks of the guerrilla movement. The war caused further deterioration in the already primitive public health and educational structures that had thus far resulted in only 0.3% of the population qualifying as literate and “civilized.” This war of independence became successful due to the dominant role of the Balanta, who carried the brunt of the traumatic burden in terms of personal and communal losses (de Jong and Buijtenhuijs 1979). De Jong’s interpretations focused on the sociopolitical meanings of Kiyang-yang. He interpreted Kiyang-yang as a collective coping strategy for dealing with stressors originating in three fields of social change: the precarious socioeconomic position of the Balanta as an ethnic group within the newly formed state of Guinea Bissau, the position of Balanta women in relation to gender hierarchies, and postwar intergenerational tensions (de Jong 1987). This sociopolitical analysis agreed with previous analyses of social movements in religious anthropology that generally focused on a collective level, such as antiwitchcraft movements or collective possession (Richards 1935; Marwick 1950; Willis 1968; Ranger 1986; cf. Geschiere 1998; van Dijk et al. 2000; Lewis 2003 [1971]).”]

By the end of 1984 several Kiyang-yang communities were living in the bush, quite apart from the mainstream Balanta villages. . . . In interviews conducted in 2003 and 2004, Ntombikte referred to the perception that the Balanta have been very negatively regarded by surrounding peoples, and said that they face a predicament. ‘N’hala tells us to move forward,’ she said, but she added, the Balanta rarely go to hospitals and they are lax about sending children to school. She thinks not only that the Balanta are the makers of their own misfortunes, but also that witchcraft accusations have been instrumental in keeping them ‘backward.’ . . .

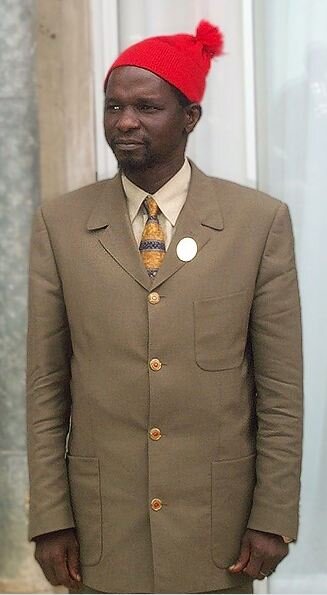

Viriato Pam and Paulo Correia

By 1985 the government had started to fear the Kiyang-yang movement and sent an investigative commission to the villages. . . . Ntombikte and some of the other leaders were taken to prison in 1985 to be interrogated. When they were released, all the Kiyang-yang activities were forbidden. A few months later, Joao Bernardo Viera (henceforth Nino Viera), then president of Guinea Bissau, fearing a coup d’etat by the Balanta, imprisoned one hundred and fifty of them (mostly those working in the army and the government). Viriato Pam and Paulo Correia (two important politicians) were accused of conspiring against the state and spreading disorder among the Balanta with the assistance of the Kiyang-yang and were executed. . . .

In order to understand the place of the Balanta in today’s political arena, we must also look more closely at how postcolonial party politics have affected the Balanta and how they have responded.

After eleven years of a liberation struggle, Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde (at first one state) attained full sovereignty in 1974 and a one-party regime was established. In November 1980 Guinea Bissau split from Cape Verde following a military coup conducted by Nino Viera, the most famous war commander and former prime minister. Viera ascended to the presidency of Guinea Bissau with the support of the Balanta, who constituted a majority in the army.

Over the years, several potential or actual rivals were successively accused of plots and imprisoned or executed (Forrest 1992:59-60).

Despite their major contribution to the liberation war, the Balanta - accused of ‘tribalism’ by Nino Viera and his entourage - were the group most deeply affected by these party and army ‘cleansings,’ which also served to ‘de-Balantacize’ the PAIGC and the army. This process, in turn, laid the groundwork for the future development of identity politics among the Balanta.

Kumba Yala

In 1994 the first multiparty presidential and parliamentary elections took place and the Party for Social Renovation (PRS) was created with a largely Balanta constituency. With the introduction of multiparty politics, a growing political instability ensued. Political mobilization and support for the PRS candidate, Kumba Yala, was achieved by the Balanta with hardly any resources. PRS leaders walked from one village to the next and meetings were held during the night, announced by the Balanta talking drums. The PAIGC won both parliamentary and presidential elections and Nino Viera remained as President of the republic, but there were widespread accusations of fraud. After the elections, the Balantas of Cubucare, feeling aggrieved by the defeat of their presidential candidate, began a temporary ‘strike’ against the other groups -globally considered as PAIGC supporters - by refusing to exchange their surplus for upland products and by raising the price of rice. Furthermore, the liberalization of the economy (which had started in 1986) and the country’s joining of the West African Monetary Union (in 1997) resulted in a worsening of economic conditions and in popular unrest. By 1997, then, there was discontent among war veterans and among the army in general.

In June 1998 a military uprising resulted in the most serious political crisis of Guinea Bissau since independence: the 1998-99 war. Nino Viera called for the support of neighboring Senegal and the Republic of Guinea, and the country was invaded by a foreign military force. A large majority of soldiers (mostly Balanta) and civilians supported the military junta that organized itself in opposition to Nino Viera, and the war ended eleven months later with the defeat of Viera, who went into exile in Portugal.

As a result of the elections that followed the end of the war, the PRS became the main political party and its leader, Kumba Yala, was elected president of the republic. Thus a segmentary ethnic group that had been characterized by its ‘isolationist rationale’ and that after independence had lost its political elite in the successive alleged coup attempts, emerged as a major force in Guinea Bissau politics and initiated a process named by some scholars as ‘the Balantization of the state apparatus’ (Nobrega 2003:293). At the time, other ethnic groups in Cubucare were mostly pessimistic about the Balanta ability to govern, predicting high levels of corruption (e.q., ‘now power is in the hands of real thieves’) and the possibility of violence among rival groups (it was frequently stated: ‘they are going to eat each other’).

After its electoral victory in 1999, the PRS started to create grassroots organization in rural areas. Following the former political practice of the PAIGC, ‘village committees’ were elected in each Balanta village or ward of Cubucare, but they were replaced by adherents of the PRS. These new committees were composed mainly of the most highly educated and hard-working young men -and also women - who also possessed good mobilization skills and were likely therefore to become an engine of social change. . . . The Balanta began to question the legitimacy of traditional authorities, stating that ‘the land has no owners’ (the Nalu landlords) and that the regulos (petty kings) who had been created by the PAIGC could now be abolished by the PRS.

PRS rule, neverheless, was characterized by a constant change of ministers, accusations of corruption, a coup overthrowing Kumba Yala (conducted with the support of some PRS leaders), and the assassination of two armed forces chiefs of staff. IF some Balanta of Cubucare had been ‘ashamed’ of their party’s rule (at least according to comments by non-Balanta people), the coup against Kumba Yala eroded even further their trust in the party. These events, together with an on-going feeling of being marginalized by their political elite, were important in improving Balanta relations with the other ethnic groups, which had deteriorated after the end of the war.

The 2004 parliamentary elections returned power to the PAIGC. However, in organizing themselves along ethnic lines, the Balanta became a major political force. Nino Viera came back to Guinea Bissau and was able to win the second round of the presidential elections as an independent candidate, although he would not have won without the support of the Balanta. Kumba Yala - also a candidate, again, for the presidency - was excluded from the second round and decided to support Nino Viera. As an uncontested leader for the Balanta, hew was able to convince his party fellows to forgive Viera and vote for him, channeling Balanta grievances toward the PAIGC. This would have seemed an impossible task some months before the elections. For people belonging to other ethnic groups, the Balanta are ‘not clever’ (i ka jiru) and are ‘easy to fool’ (fasil ngana). They also believe that Kumba Yala ‘has power over them’ (podera ki elis) and that he received Viera’s money to change their vote. Yet, the Balanta have a different take on the issue. According to them, Kumba Yala is an intelligent leader who, seeing that he was not going to win the elections, decided to support Vieira - the candidate they knew well - in exchange for government posts; in the meantime, he was preparing himself to win the next election. They also put forth the argument that Malan Bacai Sanha, the candidate who ran against Vieira in the second round of the elections, was not only a PAIGC member, but also a Muslim who wanted all of them to convert to Islam and made derogatory political statements about non-Muslim people, such as ‘wine mouths (those who drink wine) cannot rule Guinea Bissau’. Interestingly, Kumba Yala went to Morocco following the 2005 presidential elections. There he studied Arabic, and he returned to Guinea Bissau in 2008 to stage his public conversion to Islam in the city of Gabu, the historical captial of the Fulbe Empire. This was obviously a move to appeal to the Muslim electorate on the part of a man who takes his Balanta electorate for granted. Nowadays, the Balanta are learning the logic of the modern state and using the idioms of identity politics to their own advantage. Claiming to have been marginalized and to be the largest ethnic group is an effective empowerment strategy. At the same time, they are diversifying their farming system, engaging in trade activities, changing their ways of dressing, and beginning to accept the selling of cows (so as to invest in trade, to send children to school, to put tin roofs on their houses, and to buy televisions and other consumer goods, among other things); in other words, ‘trying to be modern'. At the political level the Balanta have also revealed that they are able to unite at crucial moments (mainly for elections), although their segmentary structure, in which competition among rival groups is dominant, remains a factor that reduces their capacity to maintain power and to nurture a political elite that will be recognized by the whole nation. . . .

The Balanta have been known for their fierce resistance to any form of external power or loss of their culture, either by the adoption of a more Westernized way of living or by a conversion to Islam. This ethos of enclosure - a legacy of the slave trade - was indeed instrumental in Balanta resilience to precolonial and colonial oppression. However, it also resulted in deep intergenerational and intergender tensions and in the marginalization of the whole group. The PAIGC political mobilization and the war of independence introduced fundamental changes in Balanta culture and in young men’s freedom. . . .

Post independence market and agricultural policies have ultimately been leading the Balanta to abandon mangrove-swamp rice production and to engage in cashew-tree cultivation instead. This activity allows them not only to obtain money or rice (in exchange for cashew nuts) with a very low labor input, but also to access large quantities of an alcoholic beverage produced with the cashew apple that also constitutes a good source of cash income. This change in the farming system corresponds to an increased integration into the market economy. In this way the Balanta are losing their specific niche that favored the maintenance of their strategy of ‘progressive change’ and are opening the war to wider transformation.”