-

December 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 ARCHIVE Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 SANKOFA - HOW RAS NATHANIEL FIRST RETURNED TO AFRICA AND HOW HE EMERGED AS SIPHIWE BALEKA Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 17, 2025 SANKOFA - REMEMBERING THE AFRICAN UNION GRAND DEBATE ON THE UNITED STATES OF AFRICA : SIPHIWE BALEKA'S REPORTS FROM ACCRA, GHANA IN 2007 TO THE BIRTH OF THE PAN AFRICAN FEDERALIST MOVEMENT IN 2015 Dec 17, 2025

- November 2025

-

October 2025

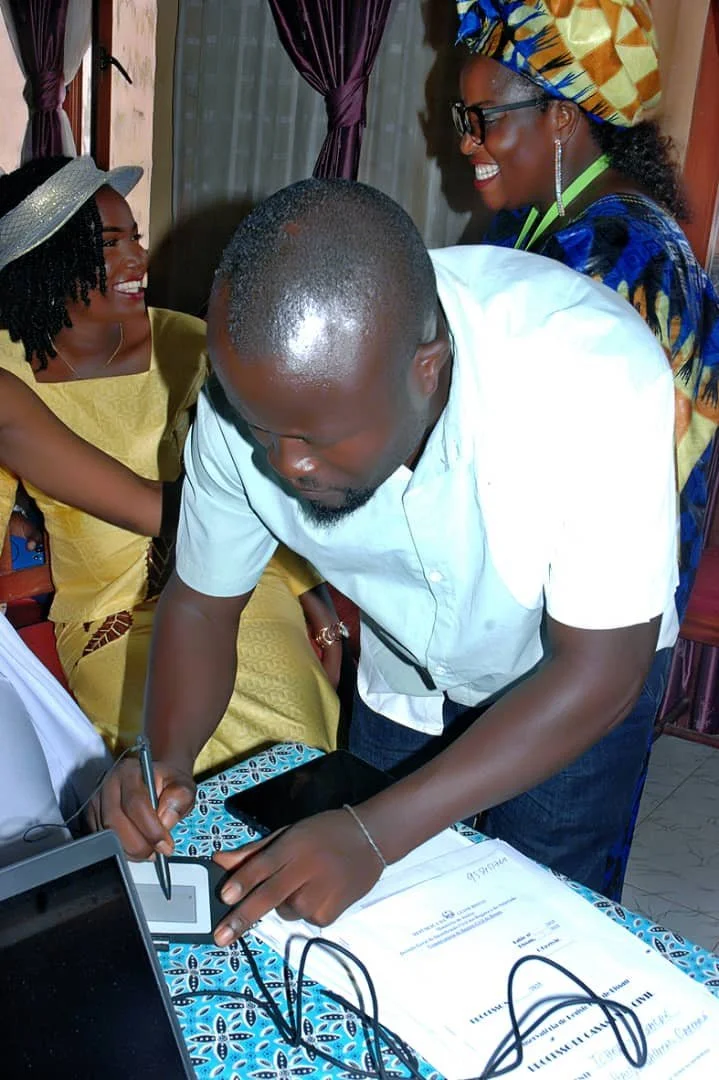

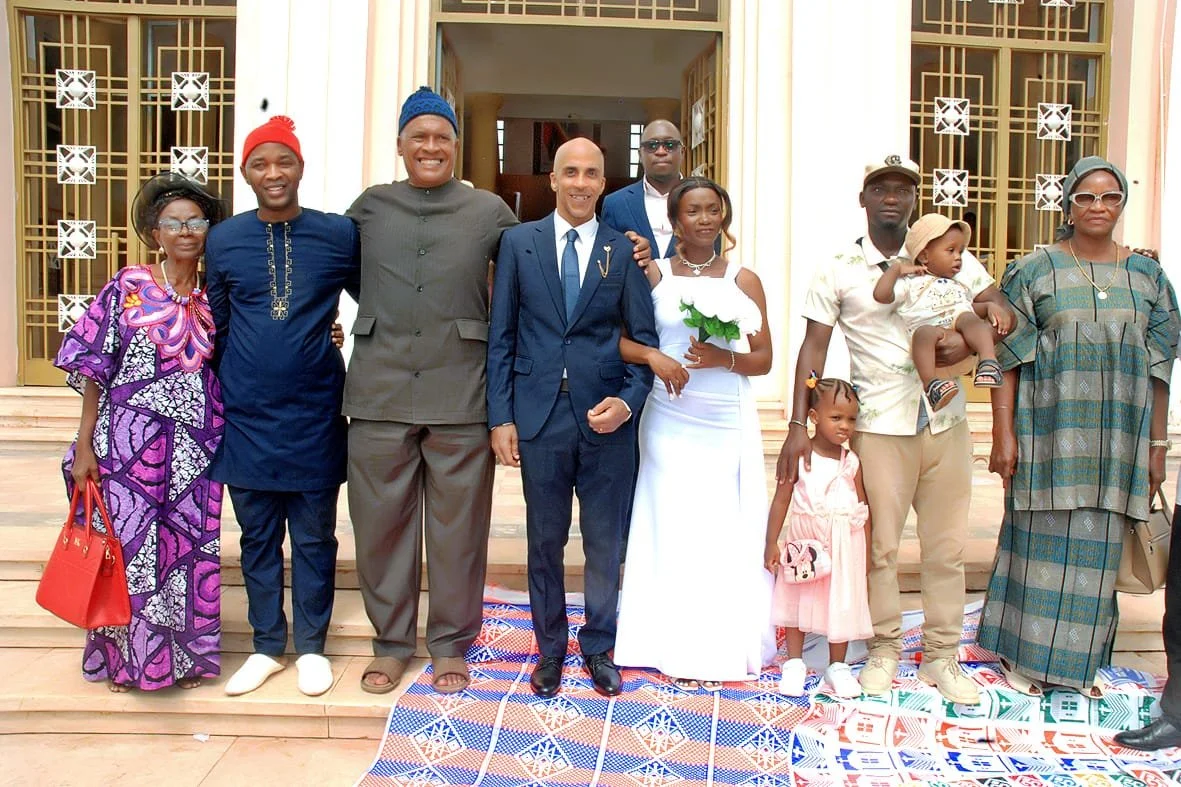

- Oct 12, 2025 Siphiwe Baleka and Sânebickté Juliana Yala Nhanca Official Wedding Album Oct 12, 2025

-

September 2025

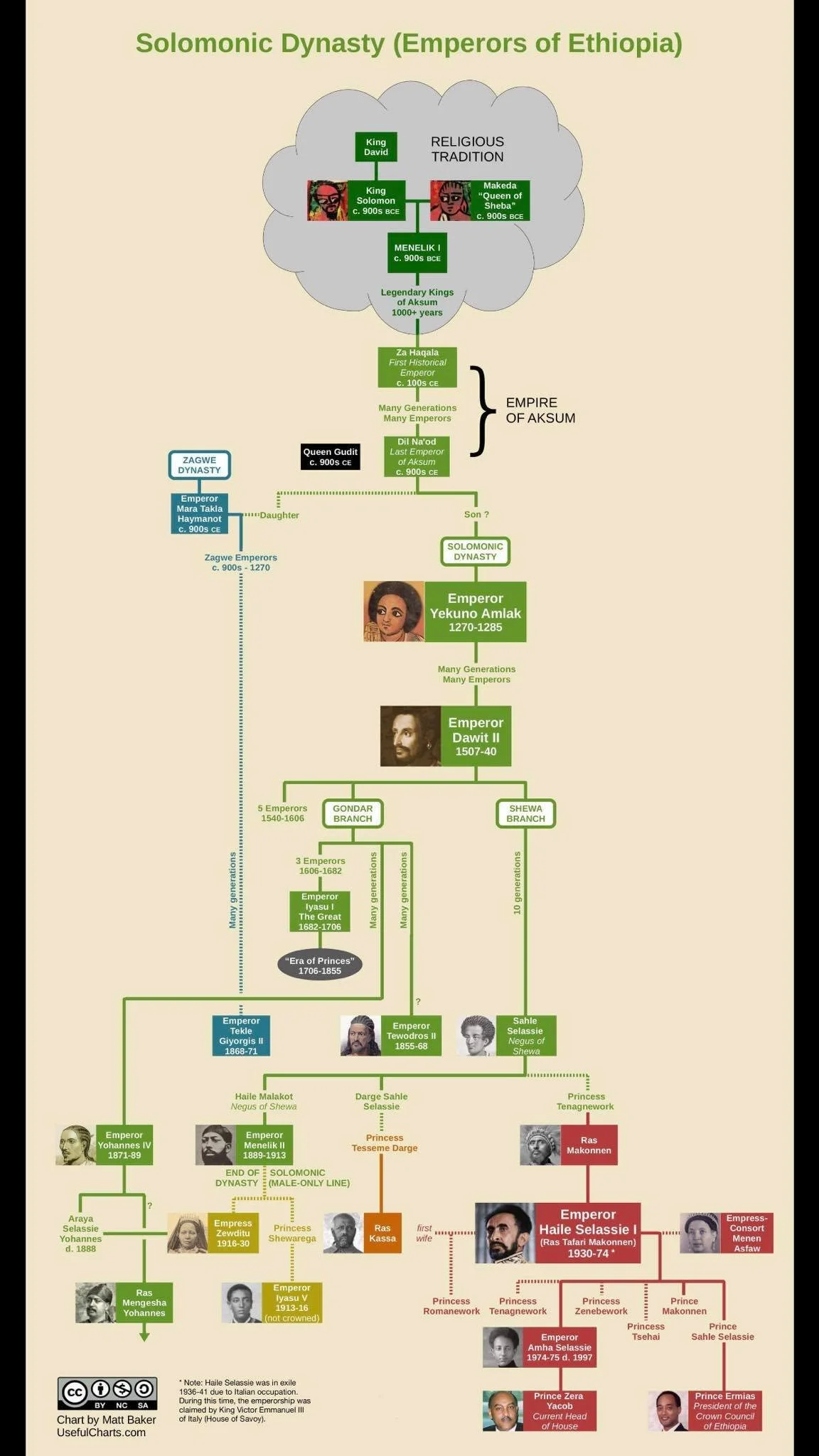

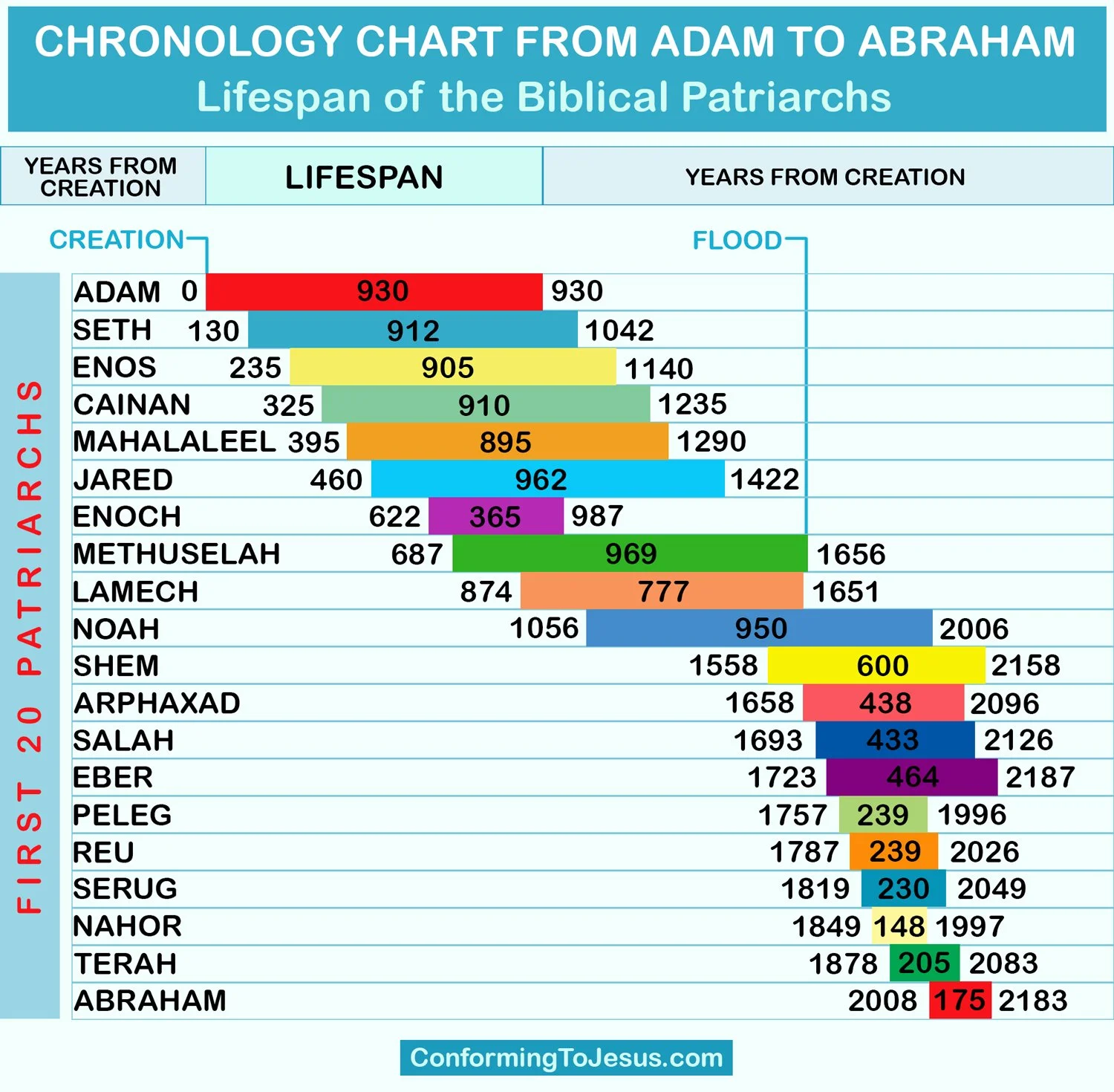

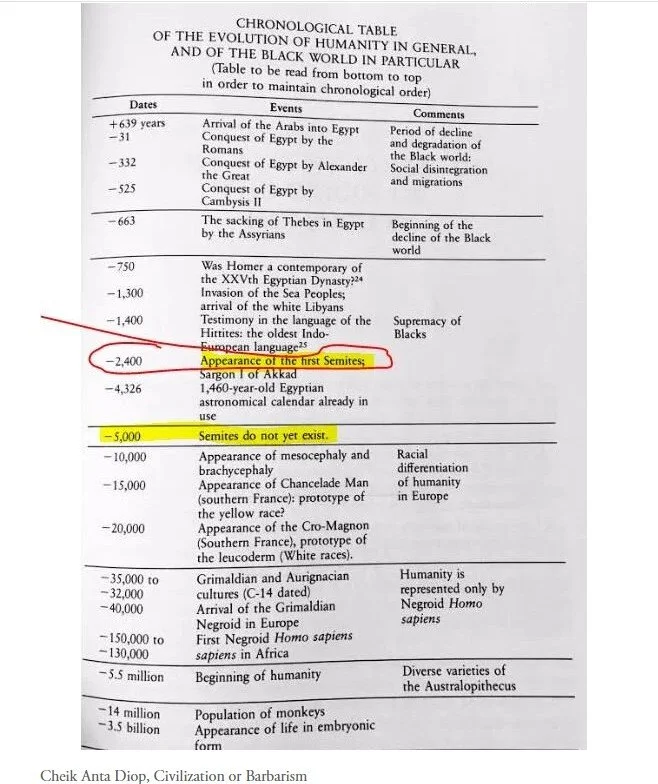

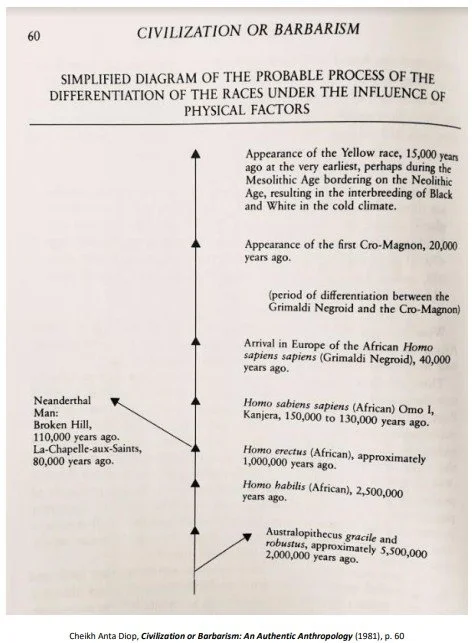

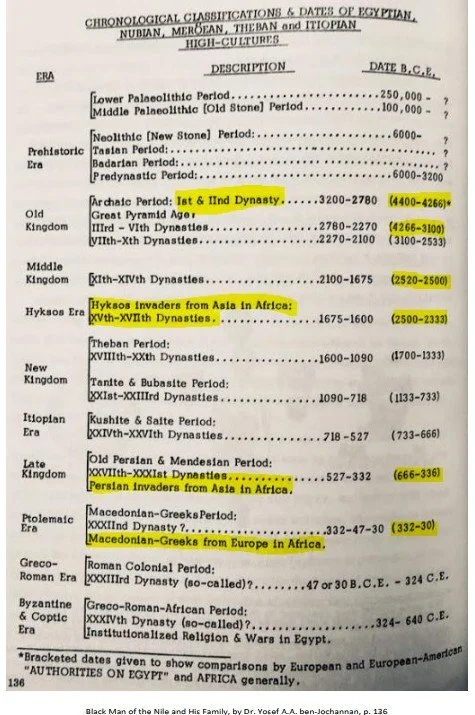

- Sep 17, 2025 A BALANTA RASTAFARITE BIBLE STUDY: FROM ISRAEL, JUDAH, DAVID, SOLOMON AND SHEBA TO MENELIK AND RAS TAFARI - HAILE SELASSIE I KING OF KINGS, LORD OF LORDS, CONQUERING LION OF JUDAH AND ELECT OF GOD Sep 17, 2025

- Sep 16, 2025 A BALANTA RASTAFARITE BIBLE STUDY: IN THE BEGINNING, FROM A BLACK CUSHITIC ETHIOPIAN ADAM AND NOAH TO A MIXED SEMITIC WHITE ABRA-HAM AND MOSES Sep 16, 2025

-

May 2025

- May 23, 2025 Omowale Malcolm X and the Republic of New Afrika May 23, 2025

- May 5, 2025 HISTORY OF THE MODERN REPARATIONS MOVEMENT THAT STARTED IN THE UNITED STATES AND HAS SPREAD THROUGHOUT THE AFRICAN WORLD May 5, 2025

-

April 2025

- Apr 1, 2025 The Military Order of Jesus Christ in Portugal Started the Misnamed TransAtlantic Slave Trade Apr 1, 2025

-

March 2025

- Mar 24, 2025 THE PAN AFRICAN, REPATRIATION, BACK-TO-AFRICA HISTORY THAT YOU WERE NOT TOLD Mar 24, 2025

- Mar 21, 2025 Malcom X Speaks on Reparations Mar 21, 2025

- January 2025

-

October 2024

- Oct 22, 2024 THE TRUE STORY OF THE 9TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS - ALL THE BACKGROUND Oct 22, 2024

-

September 2024

- Sep 7, 2024 Dr. John Henrik Clarke - African Americans the lonely nation away from home Sep 7, 2024

-

August 2024

- Aug 31, 2024 AN ANSWER TO THOSE WHO SHIFT THE BLAME TO AFRICANS FOR SELLING THEIR OWN PEOPLE INTO CHATTEL SLAVERY IN THE AMERICAS Aug 31, 2024

- Aug 18, 2024 IMARI OBADELE ON MALCOLM X AND REPARATIONS Aug 18, 2024

- Aug 17, 2024 𝐏𝐆𝐑𝐍𝐀 𝐅𝐨𝐫𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐧 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫𝐬 𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲 - Queen Mother Audley Moore's Speech to the Summit Meeting of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Kampala, Uganda - July 28, 1975 Aug 17, 2024

- Aug 15, 2024 THE ABSENCE OF THE BLACK NATIONALISTS IN TODAY’S REPARATIONS MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES: A FAILURE TO LEARN THE LESSONS OF HISTORY Aug 15, 2024

- Aug 13, 2024 CULTURAL CARRYOVERS, EPIGENETICS AND CONNECTING THE DOTS: BALANTA, PALMERES AND THE REPUBLIC OF NEW AFRIKA - A TRADITION OF LIBERATION, INDEPENDENCE AND REPARATIONS Aug 13, 2024

-

June 2024

- Jun 28, 2024 THE UNITED STATES AND ITS COLONIAL EMPIRE Jun 28, 2024

- June 2023

-

March 2023

- Mar 14, 2023 Outcome of the 4th Preparatory Meeting for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1: Pan African TV and Radio Mar 14, 2023

- Mar 14, 2023 Council of Pan African Diaspora Elders Letter of Support to President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa of The Republic of Zimbabwe for the 8PAC1 Mar 14, 2023

- Mar 9, 2023 Outcome of the 3rd Preparatory Meeting for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1: Diaspora Pan African Capital Fund Mar 9, 2023

- Mar 3, 2023 TOWARDS THE 8TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS PART 1: LESSONS FROM THE 6TH PAC AND 7TH PAC Mar 3, 2023

- Mar 2, 2023 Divide and Conquer Diplomacy of Lisbon and Washington 1973: Coopting the PAIGC and the Balanta People Mar 2, 2023

-

February 2023

- Feb 28, 2023 The African Union and the African Diaspora - Tracking the AU 6th Region Initiative and the Right to Return Citizenship: A Resource for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1 in Harare, Zimbabwe Feb 28, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 PREPARING FOR THE AFRO DESCENDANT/NEW AFRIKAN PLEBISCITE FOR SELF DETERMINATION IN THE UNITED STATES: UNDERSTANDING THE BERLIN CONFERENCE OF 1884 Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 PREPARING FOR THE AFRO DESCENDANT/NEW AFRIKAN PLEBISCITE FOR SELF DETERMINATION IN THE UNITED STATES: UNDERSTANDING DECOLONIZATION Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 PLEBISCITES IN WORLD HISTORY Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 27, 2023 African Liberation and the Use of Plebiscites Feb 27, 2023

- Feb 25, 2023 OUTCOME OF SECOND PREPARATORY MEETING FOR THE 8TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS PART 1 IN HARARE, ZIMBABWE Feb 25, 2023

- Feb 20, 2023 Outcome of the First Preparatory Meeting for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1 in Harare, Zimbabwe Feb 20, 2023

- Feb 19, 2023 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MODERN RIGHT TO RETURN CITIZENSHIP MOVEMENT SINCE THE BERLIN CONFERENCE 1884: A PRESENTATION TO THE 8TH PAC PART 1 PREPARATORY MEETING DISCUSSING PATHWAYS TO CITIZENSHIP Feb 19, 2023

- Feb 14, 2023 Defining the Afro Descendants' Right to Return (RTR) to their Ancestral Homelands on the African Continent for the 8PAC Part 1 Feb 14, 2023

-

December 2022

- Dec 25, 2022 The African American Case for Independence at the International Court of Justice Dec 25, 2022

-

November 2022

- Nov 3, 2022 Secrets of the Forest People: Learning the Bantu Culture in Cameroon Nov 3, 2022

-

October 2022

- Oct 19, 2022 Celebrating the 50 Year Anniversary of Amilcar Cabral's Meeting With African Americans, October 20, 1972 Oct 19, 2022

-

September 2022

- Sep 7, 2022 THE POTENTIAL OF A MINORITY REVOLUTION IN THE USA - The Crusader, August 1965 Sep 7, 2022

- Sep 7, 2022 THE AFRICAN LIBERATION READER Sep 7, 2022

- August 2022

-

July 2022

- Jul 20, 2022 DESCENDENTES DE BALANTA LIDERAM MOVIMENTO DE REPARAÇÃO NO VATICANO: RESPONSABILIZAM OS REPRESENTANTES DE JESUS CRISTO PELA ESCRAVAÇÃO DOS POVOS AFRICANO Jul 20, 2022

- Jul 20, 2022 BALANTA DESCENDANTS LEAD REPARATIONS MOVEMENT AT THE VATICAN: HOLD THE REPRESENTATIVES OF JESUS CHRIST RESPONSIBLE FOR THE ENSLAVEMENT OF AFRICAN PEOPLE Jul 20, 2022

- June 2022

- January 2022

-

September 2021

- Sep 23, 2021 Lessons From Amilcar Cabral and Siphiwe Baleka: The Dum Diversas War and the Incomplete Independence of Guinea Bissau Sep 23, 2021

- Sep 2, 2021 BRIEF NOTES ON BALANTA HISTORY BEFORE AND AFTER GUINEA BISSAU INDEPENDENCE Sep 2, 2021

-

August 2021

- Aug 25, 2021 BRIEF NOTES ON BALANTA MIGRATION IN GUINEA BISSAU Aug 25, 2021

- Aug 19, 2021 Jornada de Quintino Medi para descobrir a Mãe Fula de Amílcar Cabral na Guiné-Bissau Aug 19, 2021

- Aug 19, 2021 Quintino Medi's Journey to Discover Amilcar Cabral's Fula Mother in Guinea Bissau Aug 19, 2021

- Aug 8, 2021 Space and Time in the African Worldview: Excerpt from Remembering the Dismembered Continent by Ayi Kwei Armah Aug 8, 2021

-

May 2021

- May 30, 2021 Historic Moment in Guinea Bissau: Denita Madyun-Baskerville is the First Balanta Woman to Return to Her Ancestral Homeland Since the Slave Trade May 30, 2021

- May 27, 2021 Sketches of the History of Balanta People in America: Anthology Series 1 now available! May 27, 2021

- May 5, 2021 MAY 5TH - THE MOST IMPORTANT DAY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY AND EVIDENCE THAT THE ANCESTORS OF AFRICAN PEOPLE COMMUNICATE TO THEIR DESCENDANTS ON EARTH AND SHAPE WORLD EVENTS May 5, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 6, 2021 CLARIFYING THE POLITICAL AND LEGAL STATUS OF 1,108 GENERATIONS OF MY FAMILY Apr 6, 2021

-

March 2021

- Mar 23, 2021 Balanta Marriage Customs: KWÂSSI, B-BÂSTI and MHÂH M-NANHI Mar 23, 2021

- February 2021

-

November 2020

- Nov 24, 2020 Oligarchy: The Spiritual and International Legal Wars Against the Balanta Nov 24, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 25, 2020 The Civil, Political and Legal Illiteracy of African Americans: Failure to Apply the Framework of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Oct 25, 2020

- Oct 11, 2020 Notes on Hugo Grotius' Commentary on the Law of Prize and Booty (1604) Oct 11, 2020

- Oct 10, 2020 The Spiritual Protective Function of the Balanta Placenta Tradition, The United States Birth Certificate and the Spiritual Damage of Slavery Oct 10, 2020

- Oct 6, 2020 B’KINDEU & RANSOM: BALANTA PEOPLE REFUSED TO PARTICIPATE IN THE CRIMINAL EUROPEAN TRANS ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE Oct 6, 2020

- Oct 1, 2020 From Nhacra to North Carolina: The Story of Brassa Nchabra and The Blake Family, 1760 to 1890 Oct 1, 2020

-

September 2020

- Sep 7, 2020 BALANTA AND THE POISON ORDEAL Sep 7, 2020

- August 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 4, 2020 KNOW YOUR AMERICAN HISTORY: A BALANTA FAMILY ON JULY 4 1776 Jul 4, 2020

- Jul 3, 2020 LAND HAS ALWAYS BEEN CENTRAL TO THE SOLUTION OF AMERICA'S RACE PROBLEM Jul 3, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 24, 2020 The Black Liberation Movement (BLM), Balanta, Rastafari, and America's Drug War: Chicago Police Attacks on January 27, 1997 and August 6, 1999 Jun 24, 2020

- Jun 22, 2020 Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) Reader Jun 22, 2020

- Jun 21, 2020 A BALANTA PANTHER: STEPHEN HOBBS AND THE CHICAGO BLACK PANTHER PARTY Jun 21, 2020

- Jun 9, 2020 REVISITING THE BATTLE PLAN: THE STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF NEW AFRIKA TO LIBERATE BLACK AMERICANS Jun 9, 2020

- Jun 8, 2020 JUNE 8, 1954: THE MOST IMPORTANT DAY IN 20TH CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Jun 8, 2020

- Jun 2, 2020 Marcus Garvey Message to the People: Lesson 16 Propaganda (and War), The Course of African Philosophy Jun 2, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 17, 2020 THE BALANTA STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE AND EQUALITY: BRIEF SKETCHES OF ONE STRONG FAMILY'S ROLE IN AMERICAN HISTORY May 17, 2020

- May 9, 2020 KNOW YOURSELF, KNOW YOUR ENEMY: UNDERSTANDING EUROPEAN HISTORY PRIOR TO THEIR ARRIVAL IN WEST AFRICA May 9, 2020

- May 9, 2020 THE BOOK AFRICAN AMERICANS SHOULD BE READING: NOTES ON THE ORIGINS OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN INTERESTS IN INTERNATIONAL LAW May 9, 2020

- May 8, 2020 The B'rassa Fight Against the Befera: Learning from the Revolutionaries from India May 8, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 10, 2020 Black Bodies of Knowledge: Information Gangsters, Guerrillas and Notes on an Effective History by John Fiske Apr 10, 2020

- Apr 2, 2020 CREDO MUTWA ON THE RACE THAT DIED: A TALE OF TECHNOLOGY AND A WARNING TO THE FUTURE Apr 2, 2020

- March 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 19, 2020 MISSING MIDDLE PASSAGE DOCUMENTS: THE CONSEQUENCE FOR BALANTA, MENDE, TEMNE AND OTHER SENEGAMBIAN PEOPLES BROUGHT TO THE UNITED STATES Feb 19, 2020

- Feb 3, 2020 THE MALI KINGDOM AND MANSA MUSA WERE IMPERIALIST SLAVE TRADERS: REVISITING AFRICAN HISTORY FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE OPPRESSED Feb 3, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 29, 2019 AFRICAN HISTORIANS SPEAK ON BLACK-WHITE RELATIONSHIPS AND THEIR MIXED RACE OFFSPRING Dec 29, 2019

- Dec 3, 2019 Homosexuality Contemplated From African Spirituality Dec 3, 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Befera: The White Christian Witches of the Balanta Worldview Dec 1, 2019

-

November 2019

- Nov 16, 2019 Balanta and the Banking System: A Case Study of the Criminal Application of Fictitious Corporate Statutory Law Nov 16, 2019

- Nov 6, 2019 SUMMARY OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE Nov 6, 2019

- Nov 6, 2019 DEVELOPMENT OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE Nov 6, 2019

- Nov 4, 2019 Timeline of American History And The Birth of White Supremacy and White Privilege in America Nov 4, 2019

-

October 2019

- Oct 29, 2019 LEGAL ISSUES EFFECTING BALANTA AS A RESULT OF CONTACT WITH THE ENGLISH Oct 29, 2019

- Oct 29, 2019 LEGAL ISSUES EFFECTING BALANTA AS A RESULT OF CONTACT WITH EUROPEAN CHRISTIANS Oct 29, 2019

- Oct 28, 2019 DEVELOPMENT OF LEGAL ISSUES DURING THE BALANTA MIGRATION PERIOD Oct 28, 2019

- Oct 28, 2019 ORIGIN OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE IN THE UNITED STATES Oct 28, 2019

- Oct 25, 2019 HOW THE AFRICAN UNION WAS ESTABLISHED TO INCLUDE THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Oct 25, 2019

- Oct 22, 2019 THE BALANTA FOUNDER OF THE AFRICAN UNION 6TH REGION CAMPAIGN Oct 22, 2019

- Oct 18, 2019 Amilcar Cabral Describes Balanta People Oct 18, 2019

- Oct 16, 2019 AN ANSWER TO THOSE WHO CLAIM THAT AFRICAN AMERICANS ARE HEBREW OR “LOST JEWS” Oct 16, 2019

- Oct 9, 2019 26 Principles of the Great Belief of the Balanta Ancient Ancestors Oct 9, 2019

-

September 2019

- Sep 19, 2019 Reviewing the Sudanic/TaNihisi Origins of the Balanta Sep 19, 2019

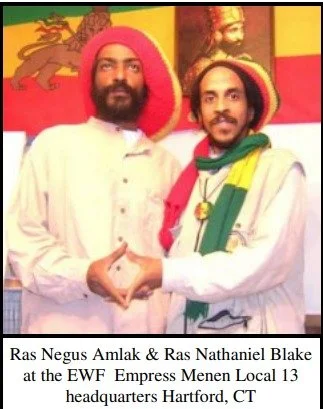

SANKOFA - HOW RAS NATHANIEL FIRST RETURNED TO AFRICA AND HOW HE EMERGED AS SIPHIWE BALEKA

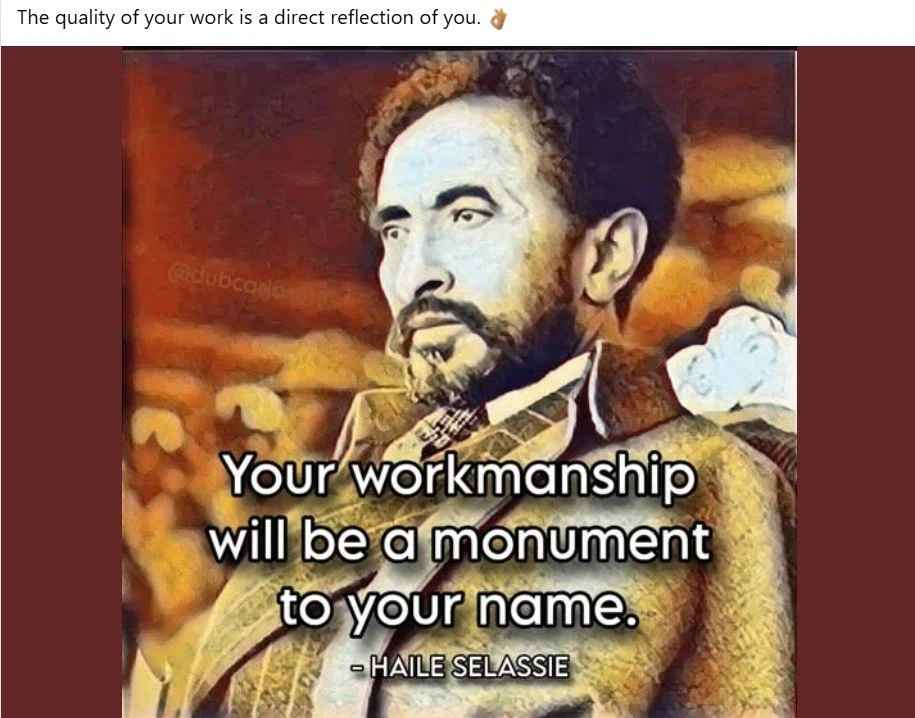

“To embark successfully in a career involving leadership demands a courageous and determined spirit. Once a person has decided upon his life’s work and is assured that in doing the work for which he is best endowed and equipped he is filling a vital need, what he then needs is faith and integrity, coupled with a courageous spirit so that no longer preferring himself to the fulfillment of his task he may address himself to the problems he must solve in order to be effective.” - Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie on Leadership - July 17, 1959

Ras Nathaniel in 2004

On October 5, 2000, I, a native of Chicago, presented the Ethiopia to Chicago Exhibit to the Association of African Historians (AAH) at the Center for Inner City Studies at Northeastern University. The presentation was so extraordinary, that I was invited to present it again one month later, November 4, 2000 to the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations (ASCAC). Five years later, Nana Baffour Amankwaitia II (Dr. Asia Hilliard III) said, “I still have my copy of the excellent piece that you did. I am waiting for more of your work. . . I am not at all surprised at the work that you have pursued and know that much more is to come.”

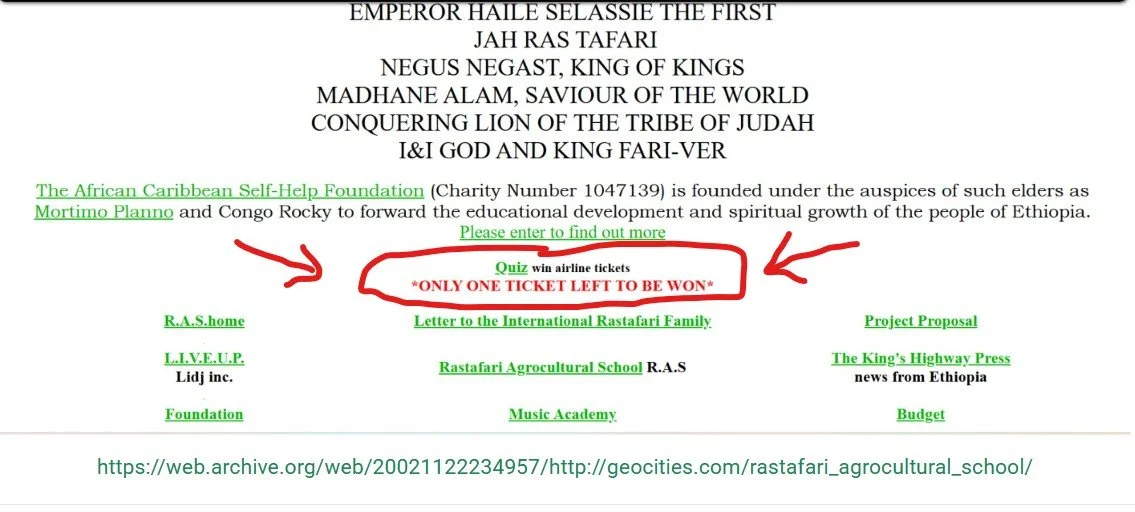

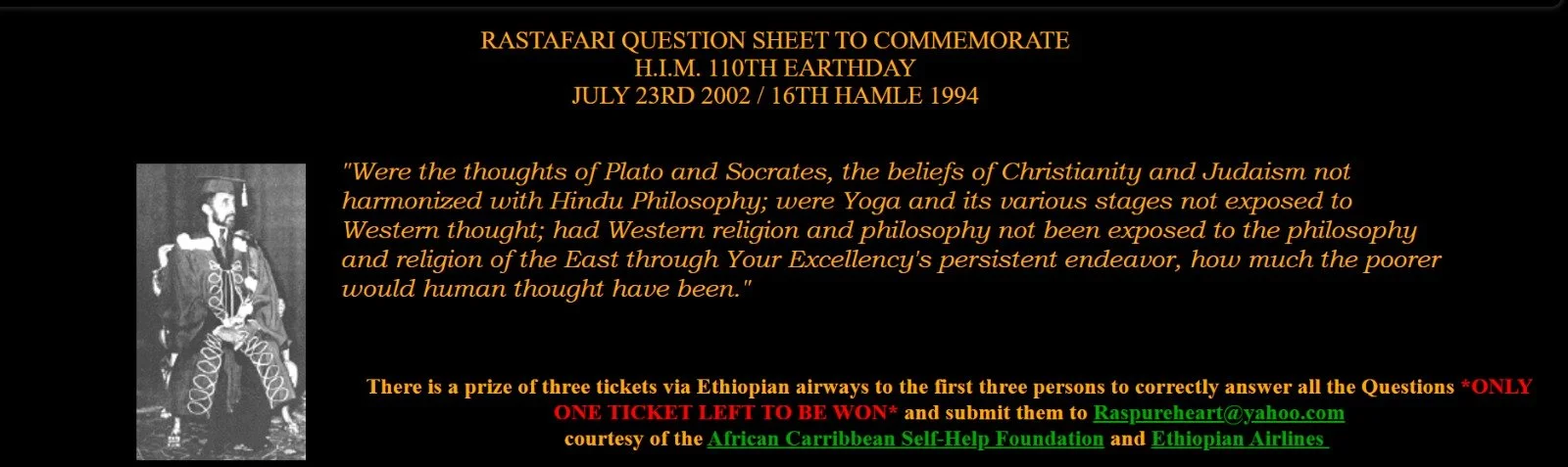

Sometime in the late fall of 2002, Ras Antar called me and said,

“Hail Ras Nathaniel. Did you see that there is a quiz on the Rastaites website? Answer all the questions correctly and you win a plane ticket to Ethiopia. You should enter the contest and take the quiz! If anyone can win, it would be you. You know more about this than anyone I know!”

Thus, I answered the quiz questions (see below) and submitted my entry for the contest sponsored by the African Caribbean Self Help Foundation and its founder, Ras Xylon, of the Rastafari Agricultural Music School in Ethiopia. I didn’t think I would win, but I entered anyway. Who knows?

I was surprised when I received an email saying that I won the contest! At the time, I lived together with my Rastafari wife, Sister Myrah. So I returned their message and told them that it was only because of her supporting me that I could gain all that knowledge to answer the questions. So impressed with this, they sent my a second email saying, “We are sending you two plane tickets - one for you and one for Sister Myrah!”

And that is how I went to Africa for the first time in my life. I didn’t buy a ticket, I earned one becasue of education and my choice to follow Rastafari. . . . . To me, that was a sign, a spiritual matter . . . . a CALLING. . . .

Ras Xylon

RAS NATHANIEL ARRIVES IN ETHIOPIA!

The following was published on the Rastaites website:

“NEWS FROM SHASHAMANE

Since May 5 2002 , there has been lots of communication between Ethiopia and the outside World of scattered Rastafari. Rastafari_Agrocultural_School web site started the Community off to a Mighty start as the Original Rastafari website in Ethiopia and Shashemene . The Site have enjoyed the fruits of Participation through networking , as great is the company of those that publish it . Through the help from H.I.M. who is at all time strengthening the efforts of I&I at R.A.S. , I&I give I-more thanks and is extremely grateful to H.I.M. for who I&I am , Blessings will continue to flow to the loyal bretheren and sistren who have made an effort to participate & communicate so as to make the reality full , Special thanks.

The Ethiopian year started in September with Jah Rastafari richest blessings, I&I at Rastafari Agro-cultural School is still working at fulfilling this portion of the works we had already started with Community Development as I&I main Focality. I&I are gratified to have contributed to the build up of interest at home and abroad , I&I received the Reggae Train Award for the Website within the first one month . Much credit goes out to Sister Mary Dread for her unswerving efforts and her personal RastaItes.com contribution which has assisted in making the Networking of Rastafari at home and abroad a fulfillment , I&I at R.A.S. I&I originally approached Ethiopian Airlines who was not able to participate at this time but pledged support in the future. I&I effectuated a Quiz page and one Ras made a wholehearted attempt and was rewarded.

On the 24th of December arrived from the Rastafari Community in Chicago, Co-ordinator of the Bright Sun Solar project, Issembly of Rastafari Iniversal Education (IRIE), Shashemane Creations . Ras Nathaniel and his wife Sister Myrah arrived in Addis Abbaba , Ethiopia and was received by Ras Wolde Tagass King of the E.W.F. Inc. , Ras Ibi and Ras Xylon of the Rastafari Agrocultural School Project. Ras Nathaniel is the recipient of the Rastafari_Agrocultural_School Quiz and was Awarded two airline tickets courtesy of the R.A.S. Project

Ras Nathaniel brought along with him 5 boxes of Organic Soyabean Seeds weighing over 150 kilo (330 lbs.) for immediate cultivation , some of these seeds was given to Ras Wolde of the Ethiopian World Federation Inc.

Ras Xylon was presented with a cheque of US$718.91 cents this will go into the operations and running of R.A.S. Project, It is agreed by our planning committee to use this fund to purchase a brick making machine so as to contribute to Construction and development of the Community.

On the following day Ras Nathaniel met the Chairman of the J.R.D.C. Ras Desmond Martin at the Hawaris Hotel where they stayed for their first night , Together I&I all trodded up to the Home of Rastafari Goahe Muuzyka Academy where I&I listened to the recording done in Shashamane with the Twelve tribes of Israel band featuring Ras Desmond Martin on lead vocals , begging for the lord , to give us a helping hand and take us to the promised land yes take us to the promised land.

I&I will continue to express I&I free thoughts as I&I experience it . Questions are being asked why is R.A.S. Project not highlighted on the new J.R.D.C. page? One of I good sistren say it is politics , an Idrens call it piracy or I would say it could be a part of a Conspiracy , but who want to do , let it be done in righteousness , when R.A.S. was effected there was no Rastafari NGO's in Shashamene and as a member of the freewill trod which the Nyahbinghi Order represents I&I as Rastafari Agro Cultural School community consultants have been doing our Projects and as it go regardless of the Sabotages I&I should get on with it through the POWER OF H.I.M. HAILE SELLASSIE 1ST.

The Ethiopian World Federation Inc. and the Jamaica Rastafari Development Community should put their petty grudges and differences aside and serve Rastafari to effect a Collectivity within Shashamene Community. Personal differences will always arise hence the need for tolerance , Word is Wind but blows is unkind. Internationally every Rastafari has the right to decide his or her moral destiny and in this judgment burn Impartiality. “

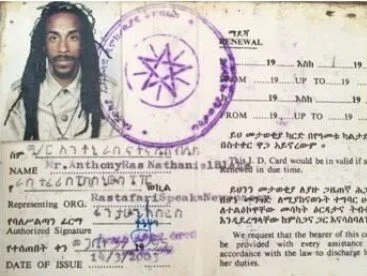

Not long after I arrived, Ras Xylon took me to get registered with the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Information & Culture Press and Information Department as a journalist for the Rastafari Speaks newspaper.

With official media credentials, I now had access to the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), the African Union (AU) and the United Nations (UN). On February 3-4, 2003, I attended the 1st Extra-Ordinary Summit of the Assembly of the African Union in Addis Ababa and began issuing reports to the African Diaspora via the internet. I was the only African American journalist in the room when the historic Article 3(q) was adopted that officially “invite(s) and encourage(s) the full participation of Africans in the Diaspora in the building of the African Union in its capacity as an important part of our Continent.” From this decision, the African Diaspora would become designated as the 6th Region of the African Union.

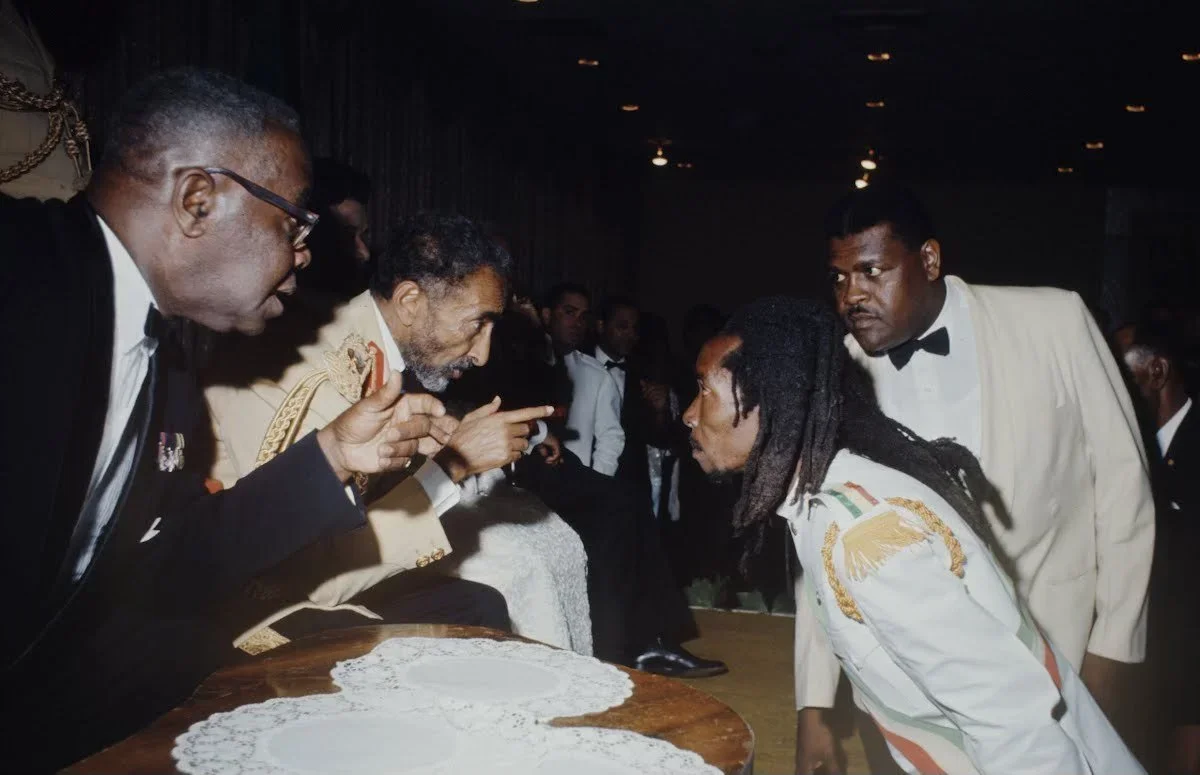

Aware that Malcom X had also been an observer at the AU’s predecessor, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), I now felt an awesome responsibility to the African Diaspora, and particularly to the Rastafari community, to keep them informed of all things related to the African Union. This I did using the Rastites website which archived all of my messages.

“I now felt an awesome responsibility to the African Diaspora, and particularly to the Rastafari community, to keep them informed of all things related to the African Union.|”

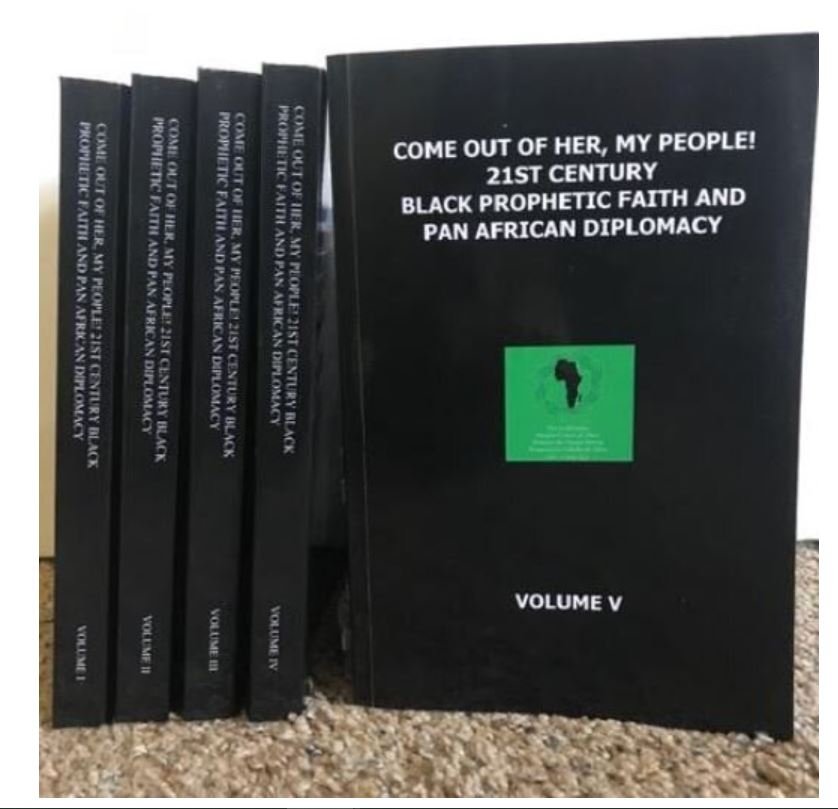

From 2002 to 2007, I was the Coordinator of the Issembly for Rastafari Iniversal Education (I.R.I.E.) which served as a Ministry of Education for the Rastafari Family Worldwide. All my work in the I.R.I.E Ministry of Education, including emails, articles, commentaries and reports are documented in the five volume, 1,500 page work entitled, COME OUT OF HER, MY PEOPLE! 21ST CENTURY BLACK PROPHETIC FAITH AND PAN AFRICAN DIPLOMACY. [See below]

Besides attending the First Extraordinary Session of the African Union, and become the Founder of the AU 6th Region Education Campaign, I also helped to negotiate the immigration issues of the Rastafri community in Shashemane. In this way I started my career after leaving Yale University as a minister of education, a minister of foreign affairs, an ambassador, an envoy and a diplomat. Indeed, I was fulfilling HIM Haile Selassie’s prophecy

“All of you young people who have been given the enriching opportunity of an advanced education will in the future be called upon to shoulder in varying degrees the responsibility for leading and serving the nation."

I returned to the United States in the late fall of 2003 in order to lead the Jubilee 50 Year Commemoration of HIM Haile Selassie I’s first visit to the United States (1954-2004). I created a traveling exhibition of more than 100 pieces that was featured at the Smithsonian. I also published a book as well. I also published a Proposal on the “HOW” to Istablish the Rastafari International Secretariat by May 25, 2004.

I was given exclusive access and permission by Ato Demeke Berhane, Director of Archives at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to publish the official photographs of HIM Halie Selassie I’s First Visit to the United States in 1954 https://www.amazon.com/Anniversary-Imperial-Majesty-Haile-Selassie/dp/1412037026

On June 8, 2004 I experienced the supernatural direct communication with HIM durning the Venus Transit. During this "astronomical event of the year" writes Carl Johan Calleman, PH.D,

“it is hard to avoid the impressions that the very transit of Venus across the Sun has somehow served to concentrate these energies and has sent an intensifying beam to planet Earth. During the Venus transits the cosmic energies were thus strongly amplified. There are however many good reasons to believe that the Venus transit on June 8, 2004. . . will herald a development of communications between human beings that is not based on technology. The chief reason is that we are now at a stage . . . that favors the right brain half and the intuitive faculties of our mind that are mediated by this. And so, we may expect that the upcoming Venus transit will launch an era of communications utilizing mental rather than electromagnetic fields. . . . Since there is no person alive today who was born in 1882 or earlier the Venus transit in 2004 will be everyone's first such experience.”

No human alive had previously witnessed one; the last one prior to that occurred on 6 December 1882. On that day in 2004 at the exact moment of the Venus Transit, I was standing on the exact spot where HIM Haile Selassie I had visited and thereby received, through this intensified concentration of energy and direct divine communication particular to HIM Haile Selassie and his Jubilee visit to Chicago, His Imperial Majesty’s theocratic appointment as the Ilect of Records of the Star Order of Ethiopia - a direct divine commission from God to bring about the Repatriation of the Afrodescendant peoples.

Throughout the rest of the year I traveled from Chicago to Atlanta to Washington DC to New York, to Hartford, to Boston and across to Los Angeles.

Rastafari mini-summit, October 21, 2003, Washington DC. Ras Nathaniel in the center. The white man in the front row (second from the right) is Jake Homiak of the Smithsonian Institute. Immediately upon returning from Ethiopia, Ras Nathaniel began mobilizing the Rastafari community in the United States for the upcoming Jubilee Commemoration of HIM Haile Selassie I First Visit to the United States in May 1954. Afterwards, Ras Nathaniel then traveled throught the Caribbean and Central America preparing for the Rastafari Inity Summit in Azania and the Ethiopian Millennium Repatriation.

From left to right: Ras Nathaniel, Ras Jaberi, Ras Ravin-I in Massachusettes

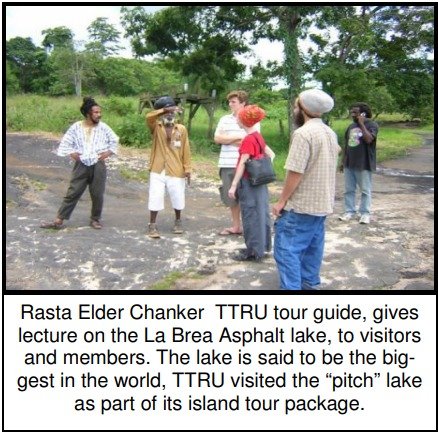

Below: Ras Nathaniel in Trinidad and Tobago 2005

Panama: Ras Nathaniel on funde drumjust left of the Ras Jaberi on bass drum. Full report: https://web.archive.org/web/20060902235707/http://www.rastaites.com/news/hearticals/panama/FinalSummitReport2005.pdf

I co-organized the First Rastafari Diasporic Summit in the Hispanic World in Panama from May 23 to May 30, 2005. In August I traveled to Trindad and Tobago and spent two weeks with the Rastafari community in Fyzabaad. I gave the Keynot Address for the Inaugural Marcus Garvey Lecture Sponsored by the Pan African Commission of Barbados at Frank Collymore Hall Bridgetown, Barbados on August 21, 2005.

Article from the Barbados Sun newspaper.

In Miami I participated in HIM Haile Selassie I Grand Coronation 75th Jubilee Celebration, November 2, 2005, and returned to Atlanta for the Ethiopian World Federation Forum. On December 23, 2005, I signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Western Hemisphere African Diaspora Network (WHADN) creating the AU 6th Region Education Campaign. Back in April 18, 2003, the African Union in conjunction with the Foundation for Democracy in Africa (FDA) and members of WHADN, announced plans for establishing technical definitions of the Diaspora and the process of effectively integrating the Diaspora into the organs and programs of the African Union, notably the Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOC). Members of WHADN and the AU delegation agreed that participants should become actively involved in this process by forwarding proposals thru the WHADN Secretariat to the AU Commission for consideration and taking ownership of the outcomes of adopted projects. It was stressed that WHADN is a network in which Diaspora organizations could freely mobilize and coordinate their interaction with the African Union on an equal basis, WHADN to serve as the “functional interface mechanism with the AU.” Among the first groups to submit a proposal to WHADN for consideration by the AU Commission was The Issembly for Rastafari Iniversal Education (IRIE). Recognizing that WHADN was “a functional interface mechanism with the AU” and “the first step of membership” in the AU 6th Region Diaspora Initiative mandated to coordinate events in 2006 to popularize the AU, I, seeking funding and more immediate and effective means towards Repatriation to Africa, sought to utilize this new mechanism to present to the African Union the Rastafari Repatriation Census Proposal for the Start of the Ethiopian Millennium (September 11,2007).

According to the proposal, “Based on results already obtained in three Repatriation Census Workshops, IRIE estimates that there is a minimum of 100 cities or locations with 100 people with various skill sets, representing a minimum of $300,000 per city plus equipment. That translates into Brain Gain of 10,000 persons and US $30 million in financial resources plus equipment available for repatriation. . . . By conducting a Repatriation Census, the African Union will immediately benefit from having a central skills technician resource database from which they could fill skills shortages in various sectors of the African Continent’s economy. . . . This proposal seeks to combine the mandate for African Union Educational Workshops with the mandate to develop a Central Diaspora Skills Resource Bank with the existing Repatriation Census Workshops being conducted by the Issembly for Rastafari Iniversal Education.” The proposal was approved and thus was born the African Union 6th Region 2006 Education Campaign with Ras Nathaniel as its Director.

Immediately after signing the MOU, from January 4 to 10, 2006, I traveled to Jamaica to strategize with the Rastafari community on that island. A plan was eventually approved to host a Rastafari Global Unity Conference in South Africa (Azania). On November 8th, I arrived in Azania. As I was preparing to depart from the plane, I heard drumming and singing. When the door opened, I saw about thirty Rastas waiting for me with Ethiopian flags. A group of Rastafari Elders of Zulu and Xhosa ancestry ascended the steps of the plane and explained to me that whenever a “son of the soil” returns home after a long journey, he receives a new name. Having journeyed far and long, the person returns as a “new” man, thus requiring a “new” name. The elders told me that while I was on ancestral soil, my ancestors required that I have an ancestral name that they could call. Thus, the elders gave me the name “Siphiwe” which means “gift of the creator” and the surname Baleka which means “fast” and “he who escaped”. This was profoundly important to me.

On November 9, I along with Ras Tekla Haymanot, Sister Yaa Ashantewaa, and Ras Gareth Prince, appeared on South African Broadcasting Company (SABC) TV Africa Live program to explain the Rastafari position.

Immediately after returning from Azania, I traveled to Honduras at the end of November for the Central American Black Organization (CABO) 12th Assembly in La Ceiba Honduras as a member of the Pan African Organizing Committee (PAOC). In Honduras, I was a roommate of elder Dr. Pauulu Kamarakafego, CEO of the Pan-African Movement to the United Nations. Dr. Kamarakafego has served as a counselor, consultant, official and friend to Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyere, CLR James, Walter Rodney and various African liberation movements. Dr. Kamarakafego was responsible for organizing the 6th Pan African Congress in Tanzania in 1969. With Dr. David Horne of the PAOC, I made a presentation on the AU 6th Region Diaspora Initiative and the process for electing the twenty representatives to the AU’s Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC).

On January 6, 2007, at the request of the Pan African Community Coalition (PACC) and the Pan Afrikan Organizing Committee (PAOC), I was invited to the New York Town Hall Meeting to discuss and supervise the election of New York’s Diaspora Representatives to the African Union (AU). After his presentation, the town hall discussed the formation of the Community Council of Elders (CCE) that conducted the election on January 27th.

With African Diaspora elections underway and spreading throughout the Diaspora, I then attended the African Union Grand Debate in Ghana in July as Coordinator for IRIE and Director of the AU 6th Region Campaign. At this event, there were many other representatives and observers from the African Diaspora. My main focus was on the AU 6th Region Diaspora Initiative, the elections for its representatives to ECOSOC, and the issue of citizenship for members of the 6th Region. I was a vocal supporter of a continental passport and setting up passport bureaus in African airports that could efficiently issue a Pan African passport to AU 6th Region members upon arrival anywhere on the continent.

Finally, working with my friend and comrade, Ras Ikael Tafari, who was the Commissioner of Pan African Affairs for the Government of Barbados, I helped to set the agenda for the Africa Diaspora Global Conference facilitated by the Republic of South Africa on behalf of the African Union, and jointly organized by the AU, CARICOM and the Government of Barbados, August 27-28, 2007. The context of the event was the Bicentennial Global Dialogue on “Slave Trade, Reconciliation and Social Justice.” I submitted a last-ditch proposal for $10 million funding from the governments in attendance, including Venezuela, Brazil and China, for the Ethiopian Millennium Repatriation and an emergency airlift of everyone that had completed Repatriation Census forms in a fashion similar to Operation Solomon, which, on Africa Day, May 25, 1991, airlifted 10,000 Ethiopian Falasha Jews to Israel, an effort kept secret by the military and organized by the American Association of Ethiopian Jews. TIn my opinion, Rastafarians had every right to be repatriated to their spiritual mecca, Ethiopia.

The proposal was rejected, September 11, 2007 came and went, and with my Five-Year Plan now ending in failure, Ras Nathaniel disappeared. On May 12, 2008, Ras Nathaniel legally changed his name to Siphiwe Baleka in order to honor his ancestors.

RASTAFARI QUIZ

What was Marcus Garvey's middle name?

Where was Marcus Garvey born?

Which Parish was Marcus Garvey born in?

Who was Alexander Bedward?

What was the name of Bedward's vision?

Who was Leonard Howell?

What other influences formed Howell's thinking?

What was the name of Howell's first camp?

When did Howell pass?

What were the circumstances of Howell's demise?

Who was Joseph Nathaniel Hibbert?

What was JNH main interest?

What was the name of JNH first organ?

Out of Dunkley, Hibbert, Howell and Hinds, who was at H.I.M. Coronation?

Who was Dunkley?

Who was Hinds?

Who was Ferdinand Ricketts?

What was the name of Ras Boanerges organ?

What was the birth date of H.I.M.?

What date was H.I.M. Crowned?

Who else was crowned with H.I.M.?

What date was the Battle of Adowa?

What date was H.I.M. speech to the League of Nations?

Which country did H.I.M. go to in exile?

How long was H.I.M. in exile?

What date did H.I.M. return to ET.?

Which country did H.I.M. pass through on his return?

What was the name of H.I.M. dog?

What year was the EWF established?

What was the name of H.I.M. official who established EWF?

Who was the first to hold office in JA of EWF?

What No. was this local?

What No. was the local in UK?

What No was the local in USA?

What date was the E.O.C. established in JA?

What date was the E.O.C. established in UK?

What date was the E.O.C. established in Trinidad?

What date was the E.O.C. established in USA?

Who was the founder of the 12 Tribes of Israel?

What was the name of the World's First International Rastafari Artist?

Name three other pioneers of conscious music.

Name four members of the original Wailers.

Give seven names of the sons of Abraham.

What was the name of Moses' wife?

What was the nationality of Moses' wife?

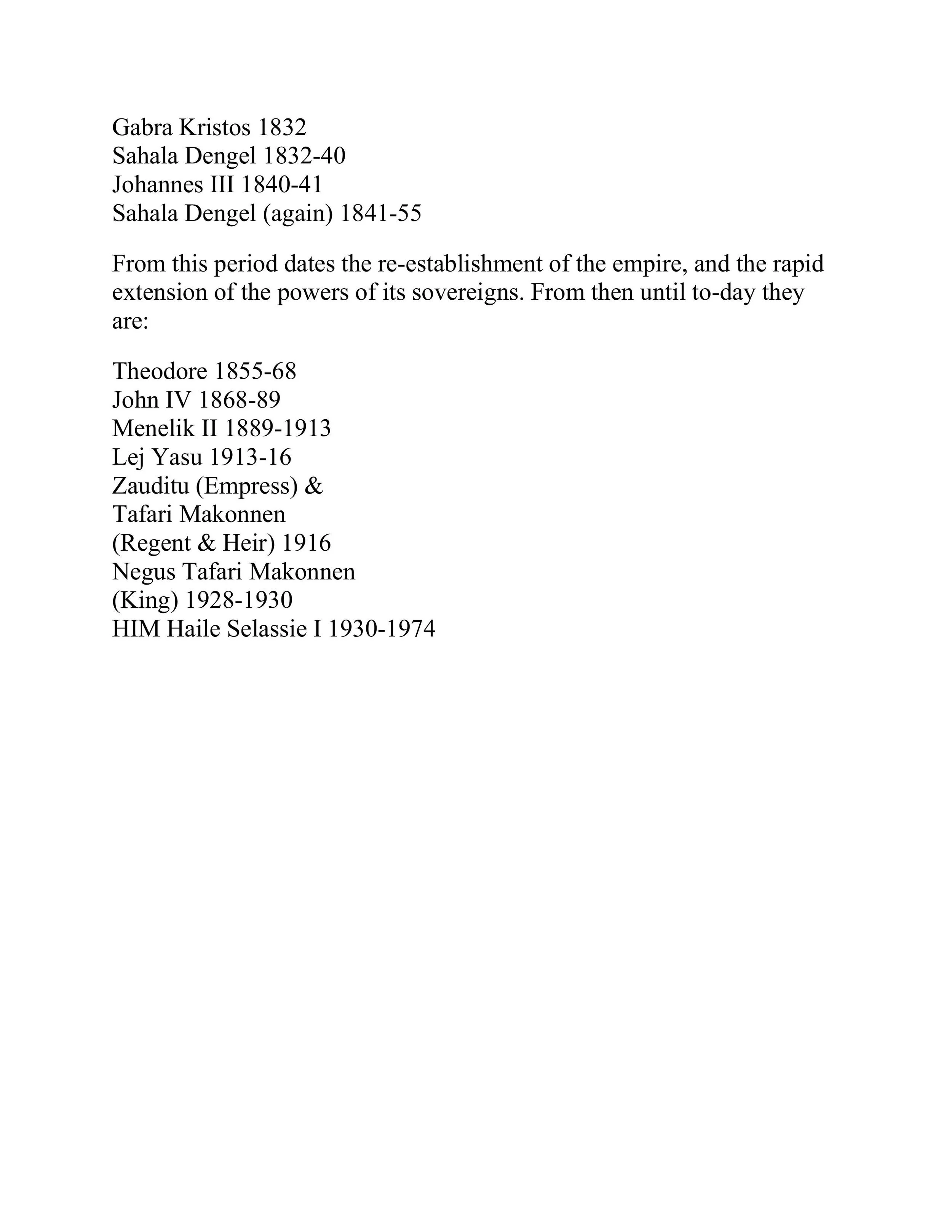

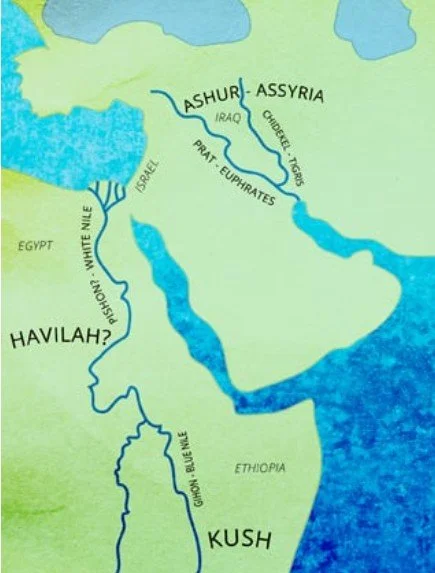

Name the four rivers mentioned in Genesis.

Name the river that encompasseth ET.

Name the river that is the source of the white Nile.

Name the lake that is the source of the Nile.

In which country is this lake?

Who or what is a 'Falasha'?

Name four of the titles given to H.I.M. on his Coronation.

Name the former capital of ET.

Name H.I.M. predecessor.

Name H.I.M. father.

Give the name of H.I.M. mother.

What is believed to have happened to H.I.M. mother.

Give the name of the first ET Patriarch.

What year did E.O.C. gain autonomy from Egypt?

Name the first Ethiopian King.

In which Parish was Pinnacle founded?

Give three other names used for ganja.

Where did the concept of locks or matted hair originate from?

Name three characters in the Bible who are known to have worn locks?

How is Solomon described in the Bible?

How is the Ancient of Days described in the Bible?

What chapter in the Bible describes the Ancient of Days?

Which character in the Bible received the vision of Revelation?

What does Revelation 5:5 state?

Which chapter in Isaiah is of great significance to Rastafarians?

Which chapter of the New Testament shows the lineage of Jesus Christ?

What relationship does Jesus the Christ hold with H.I.M.?

Was Jesus the Christ crowned whilst on Earth? (more that one answer acceptable here)

Who was John the Baptist in the bible?

How was he related to Christ?

How long did Christ spend in ET?

Did Christ visit India?

Did Christ visit Egypt?

Which Apostle is known to have taken the Gospel to India?

Which Apostle is known to have met with an Ethiopian Official?

Where in the Bible can this be found?

What is the Ancient language of ET called?

Which other country is this language known to have been used?

Name an Ethiopian King who had a burial in a Pyramid?

What are the Ethiopian colours?

How is the ET. flag different in H.I.M. time to now?

In which country, apart from JA, was H.I.M. seen as the returned Christ in the early advent of Rastafari philosophy?

What was H.I.M. family name?

What was H.I.M. name at baptism?

At what age was H.I.M. baptised?

Name one Mystical occurrence pertaining to H.I.M. at any age.

Give a general outline of H.I.M. early routine during H.I.M. Emperorship.

Give the date of the Italian Invasion preceding World War 2

Name the leader of this invasion.

Which Church blessed this invasion?

Name a Rastafarian Attorney-at-law (present).

Name a Rastafarian Historian (present).

Name a sound system that is promoting and has been promoting since the seventies Rastafari music in the UK (present).

Name the artist of the most well known group who dispelled Rastafari doctrine whose group had the initials MRR?

Name three vocal artists who have lost their lives in the field of music whilst promoting Rastafari Culture.

Which passage in the Bible qualifies the use of the name JAH for God?

compiled 21/12/1995

COME OUT OF HER, MY PEOPLE! 21ST CENTURY BLACK PROPHETIC FAITH AND PAN AFRICAN DIPLOMACY

When the World Trade Center was destroyed on September 11, 2001 – the same day that Ethiopians celebrate New Year’s Day – a few black men in America interpreted this event as the fulfillment of the biblical book of Revelations Chapter 18. Verses 4 and 5 commanded them to “Come out of her, my people, so that you will not share in her sins, that you will not receive any of her plagues; for her sins are piled up to heaven and God has remembered her crimes”. Obediently, Ras Nathaniel organized a mass Repatriation movement and led a diplomatic effort at the African Union on behalf of an estimated one million Rastafarians. There was just six years before the prophecy fulfilled for the Ethiopian Millennium which, on the western Gregorian calendar would begin on September 11, 2007.

In 1619, the first 20 Africans were brought to Jamestown, Virginia. They all had one common desire: return to their home in Africa. In every period since that time to the present, the most learned, respected and courageous of the Africans and their descendants concluded that they must either revolt against their enslavers or find some way to return to their home, the land which the Bible called “Ethiopia”. From this land a Universal Black King would be born with the titles King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of Judah. Biblical prophets claimed that Princes would come out of her, that Ethiopia would stretch forth her hands, and her scattered, captive children would be brought home. In every period in American history, black men remained faithful to these scriptures and rejected America’s forced assimilation. Men like

George Liele, 1783

Prince Hall 1787

John Marrant 1791

Robert Alexander Young 1829

David Walker 1829

Martin Delaney 1836-1852

Henry Highland Garnett 1843

Edward Wilmott Blyden 1860’s

Bishop Henry McNeil Turner 1880

William Ellis 1903

Robert Athly Rogers, 1913-1924

Grover Redding, 1917

Clayton Adams (Charles Henry Holmes) 1917

Reverend James Morris Webb 1919-1925

Marcus Garvey 1919-1924

Malcolm X 1964

Ras Nathaniel adds his name to the list.

Come Out of Her My People! tells the story of how these biblical prophesies actually happened in the 20th Century and how the Black Exodus of Rastafari people ultimately failed.

Contents Introduction......................................................................... 0

Report on Shashemane Solar PV......................................... 5

AU, President Mbeki on African Diasopora.......................18

HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL RASTAFARI CONFERENCE IN 2004 (USA).............................................................23

Letter to the African Union ...............................................30

Answers to Repatriation Questions received and answered by Ras Nathaniel................................................................36

HER IMPERIAL MAJESTY EMPRESS MENEN SLAYS THE DRAGON!...........................................................................39

REASONED STEPS TOWARDS REPATRIATION TO ETHIOPIA: STAR ORDER FIVE YEAR PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS........43

NATIONALITY, NATURALIZATION AND CITIZENSHIP ISSUES: ETHIOPIAN LAW OF INTEREST TO THE RASTAFARI FAMILY...............................................................................59

REPATRIATION CENSUS UPDATE.......................................65

More Istory of OAARU/Rastafari National Conference.....67

Rastafari at the African Union Update ..............................75

ZION PSALM 1600 DAYS BEFORE THE ETHIOPIAN MILLENNIUM.....................................................................79

April 21, 2003 Grounation Day and Rastafari Repatriation ...........................................................................................84

April 22, 2003 RASTAFARI GROUNDATION AT THE AFRICAN UNION ...............................................................................89

May 5, 2003 May 5th Great Ethiopian Anniversary .........93

IRIE STAR ORDER REPORT HISTORY OF THE AFRICAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY (AEC) UP TO THE CREATION OF 3 THE NEW PARTNERSHIP FOR AFRICA’S DEVELOPMENT (NEPAD).............................................................................96

ISSEMBLY FOR RASTAFARI INIVERSAL EDUCATION (IRIE) STAR ORDER REPORT: ETHIOPIAN IMMIGRATION POLICY AND THE RASTAFARI FAMILY WORLDWIDE........108

ISSEMBLY FOR RASTAFARI INIVERSAL EDUCATION (IRIE) STAR ORDER REPORT: UPDATE ON ASSIGNMENTS AND SPECIFIC, MEASURABLE COURSES OF ACTION MAY 2003 .........................................................................................122

RASTAFARI FAMILY WORLDWIDE SUGGESTED REPATRIATION TALKING POINTS FOR FOR THE AFRICAN UNION........................................153

A ZION PSALM 1555 DAYS BEFORE ANOTHER ETHIOPIAN MILLENNIUM ................................................161

SHASHEMANE CONTROVERSIES......................................167

September 18, 2003 Towrds Rastafari Repatriation By The Ethiopian Millennium......................................................184

African Union, NEPAD & Development.......................189

Setting the Stage & the Way Forward.........................195

"Citizen" Centered Development................................196

Consumption, World Consumerism, and African Development...............................................................201

Reconnecting with the Diaspora ................................. 205

Defining Diaspora ........................................................207

Culture as the missing link...........................................213

Rastafari as The Pan African Spiritual and Cultural Leaders........................................................................216

Rastafari Culture (“Way of life”)..................................226

Pro-Human Development ...........................................233 4

The Abdominal Brain: The Central Brain in the Solar Plexus ..........................................................................235

The Holy Herb: Sacrament and Incense for the Holy Temple of the Body .....................................................240

Marginalization from Mainstream ..............................252

Marginalization from OAU/AU....................................256

1980-2003 Rastafari Communications to the OAU.....258

Reparations over Repatriation.....................................260

Repatriation: The Way Forward..................................263

Repatriation According to HIM................................279

The Problems of Ethiopia's Development Post WWII . 284

Repatriation in the context of NEPAD.........................287

Obstacles to Repatriation............................................292

Obstacles to Repatriation Outside the Rastafari Movemant...................................................................306

Land.............................................................................315

Cannabis/Hemp/Ganja as Public Enemy #1 ................327

African Elite Fear of the Rastafari Judgment...............335

Solution: Recognition of Diaspora's Right of Return, Instant AU Citizenship at Airport Bureaus, Land, Hemp Cultivation and an Enabling Environment...................337

Kwankwa: The Missing Link in Rastafari Repatriation and African Development ..................................................337

Africa Must Be Free.....................................................350

Holy Order of Commitment and Counter-Elite ...........352

REFERENCES: ...............................................................354

21st October 2003 A Rastafari Mini-Summit in Washington D.C. ..................................................................................363

Istory of Nyahbinghi ........................................................367

Proposal on the "HOW" to Istablish the Rastafari International Secretariat BY May 25, 2004 .....................374

About Professor Ted Vestal in Stillwater, OK ..................385

AN INTERVIEW WITH RAS XYLON, ETHIOPIA'S "GOVERNOR GENERAL" ........................................................................385

January 1, 2004 HIM Jubilee in America (1954-2004) Opens .........................................................................................394

January 15, 2004 IRIE/OAARU EAST COAST TROD REPORT .........................................................................................407

IRIE/OAARU RE: EXHIBIT AT THE SMITHSONIAN.............419

Re: Ethiopian Viewpoint on African Diaspora .................428

Unity for Repatriation + The Rebirth of Black Starliner II 438

Rasponse to EMF report March 17th..............................451

The Need for Global Rastafar Government.....................458

A VERY SERIOUS MESSAGE TO THE RASTAFARI FAMILY WORLDWIDE 1,257 DAYS BEFORE THE ETHIOPIAN MILLENNIUM...................................................................458

From the Rastafari Community in Washington, D.C. RE: H.I.M. first visit to Washington Jubilee ......................470

MORE SHASHEMANE CONTROVERSIES...........................474

Subject: Re: Visiting Scholar of Ethiopian – African American relationship Atlanta ........................................488

The Issembly For Rastafari Iniversal Education (IRIE) in association with Addis Addarash presents The Jubilee Commemoration Exhibition of His Imperial Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I 1954 50 days visit from May 25thJuly 12th to the United States, Canada & Mexico...........489

May 25, 2004 An Open Letter to George W. Bush..........492

HIM Haile Selassie and Brown v Board case....................501

June 8 Jubilee/Venus Transvers Convergence in Chicago .........................................................................................512

August 2, 2004 Atlanta Jubilee Ises Report....................523

September 11, 2004........................................................528

EWF UPDATE ...................................................................528

2004 EWF/OAARU Report...............................................535

B.1. IRIE and EWF ........................................................535

B.2. Current EWF Situation..........................................538

Local #1 Seeking International Recognition................544

B.3. Future of the EWF1937 ........................................548

Ethiopian World Federation Chronology ....................554

March 18, 2005 ANKH SCIENCE.......................................568

HISTORICAL REALITY OF REPATRIATION .........................591

A journey to Ethiopia a Rastaman's Vision: from General Salem...............................................................................606

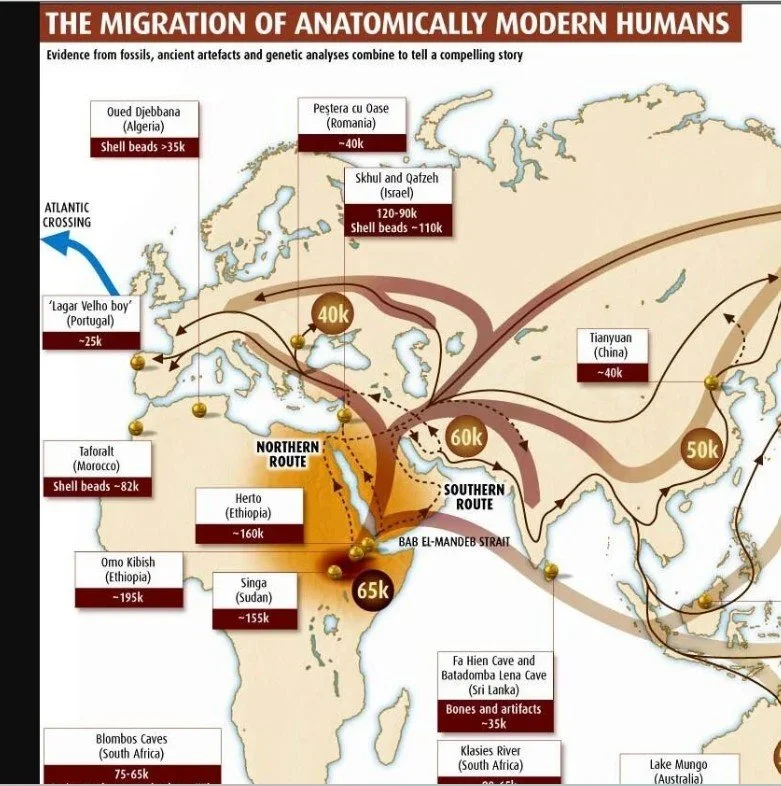

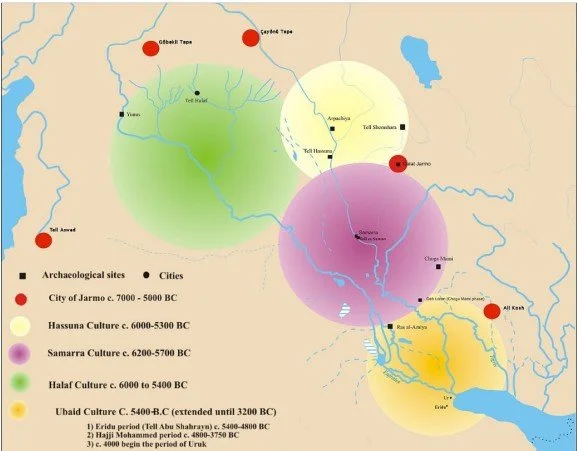

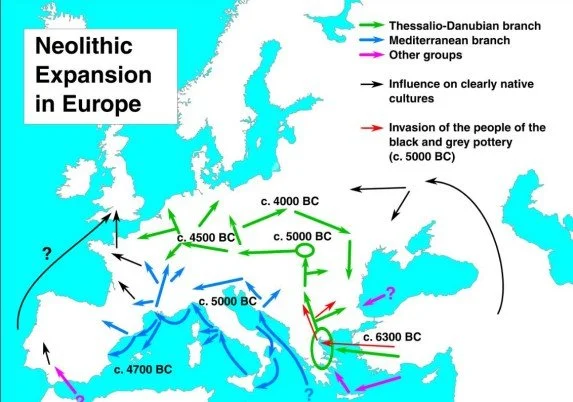

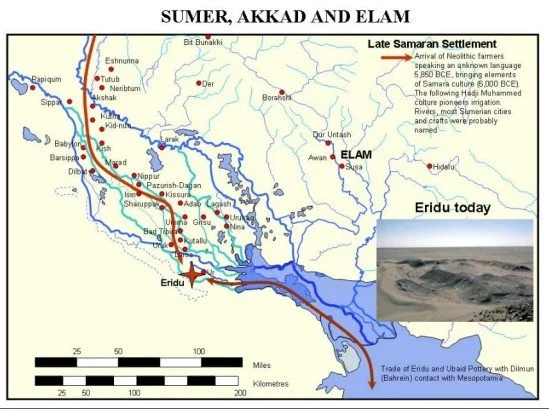

REAL ISTORY: ANU MIGRATION FROM MOUNTAINS OF THE MOON TO KMT................................................................608

THE HU/SPHINX AND THE ANCIENT MYSTERY SCHOOL OF THE ANU................................................................. 624

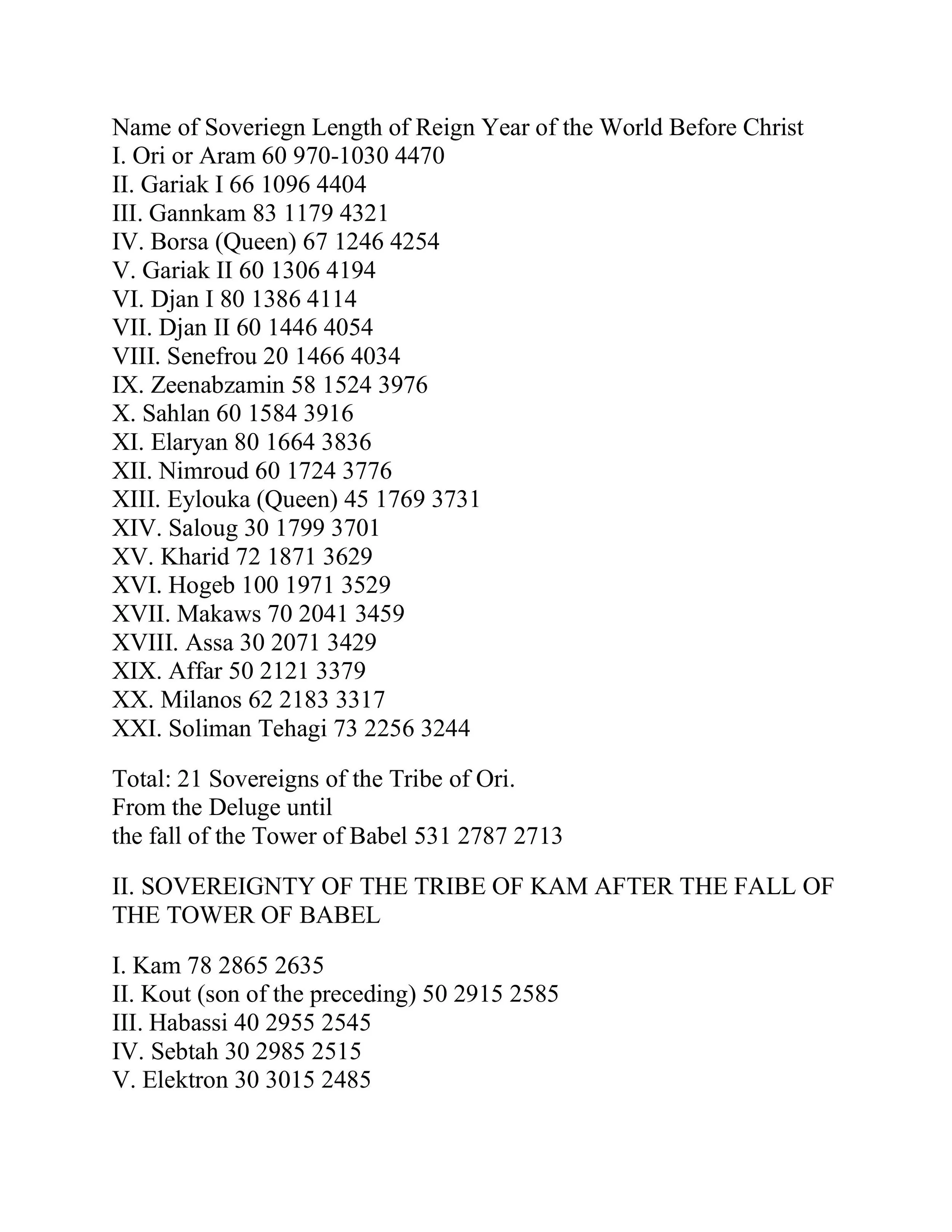

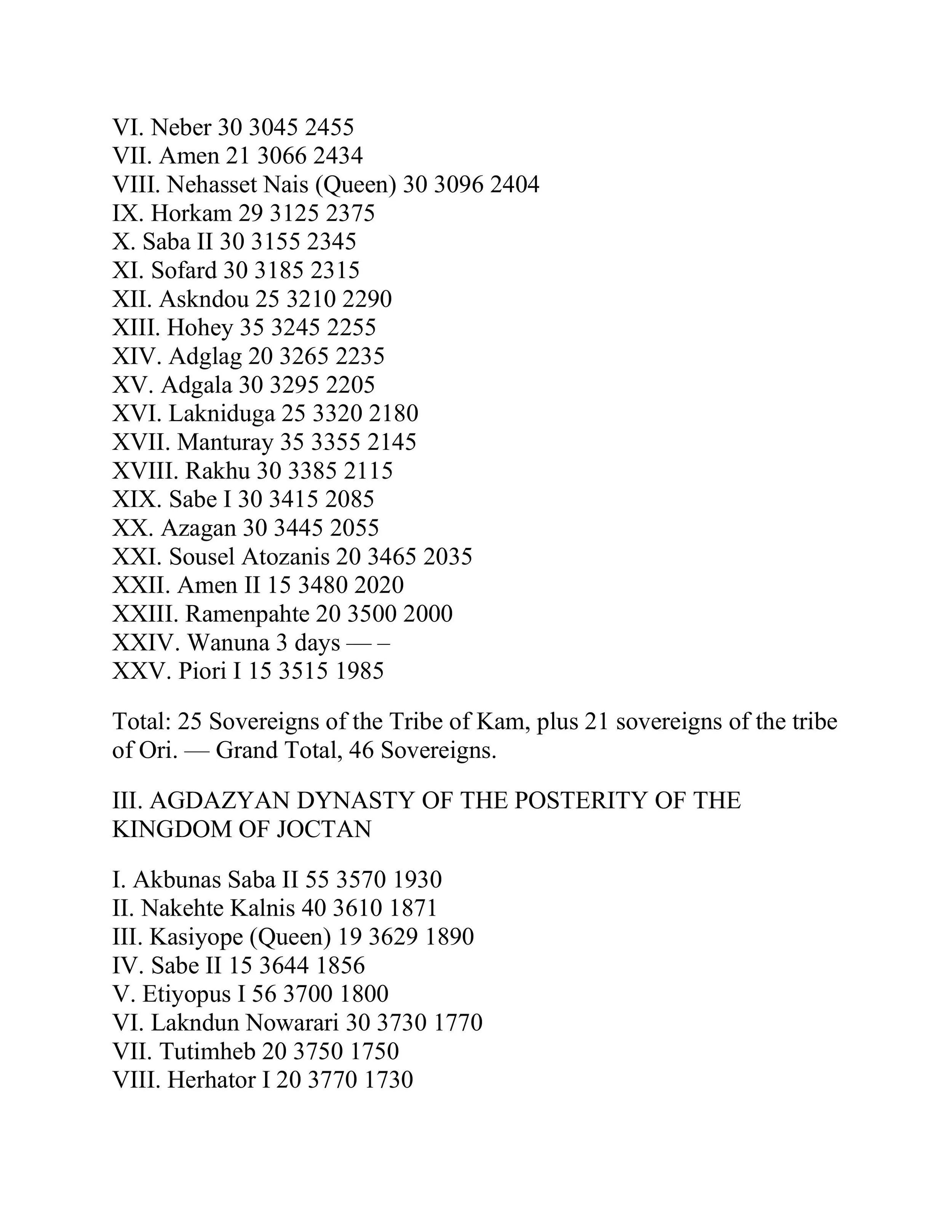

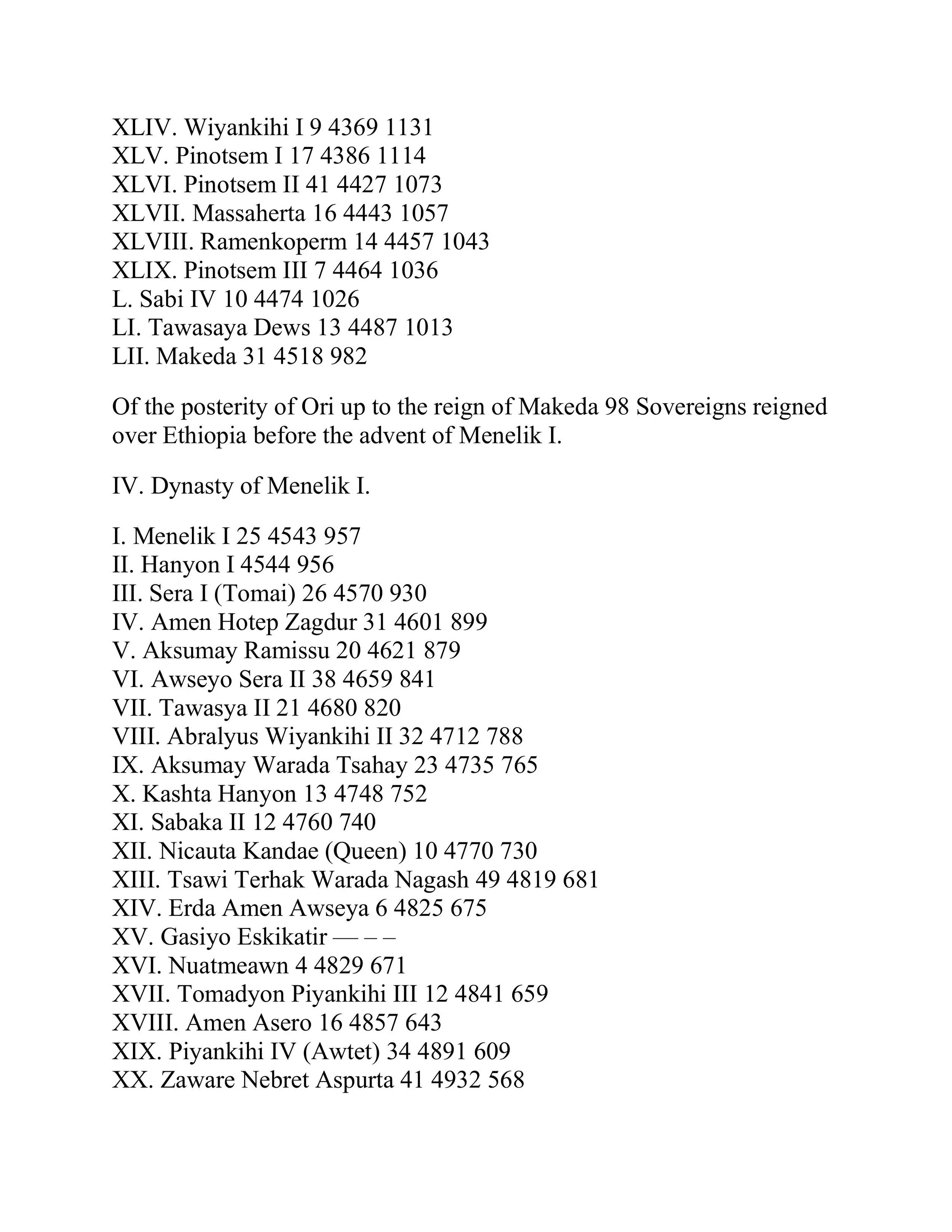

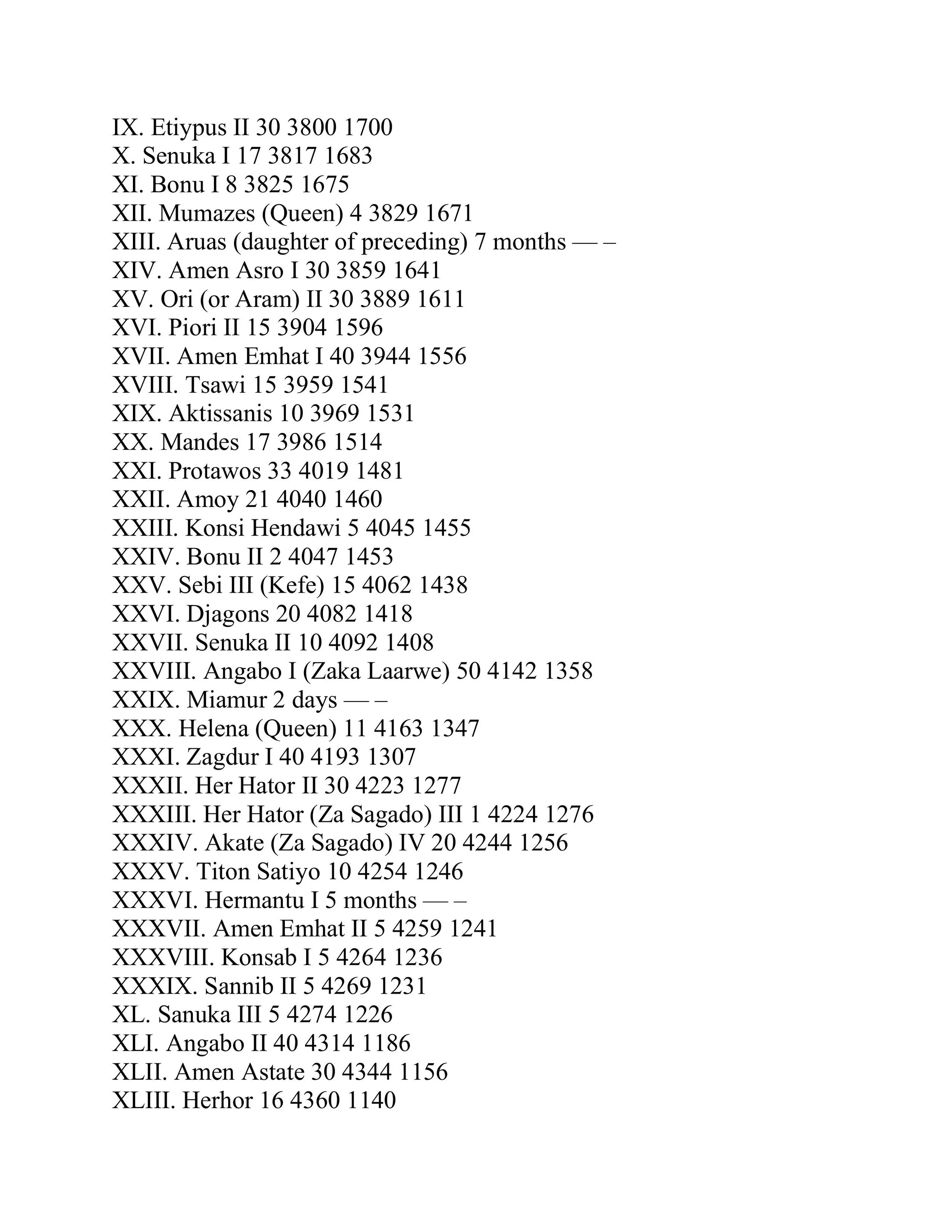

KING ORI TO KING ITIOPIA TO HAILE SELASSIE *LINK* ...633

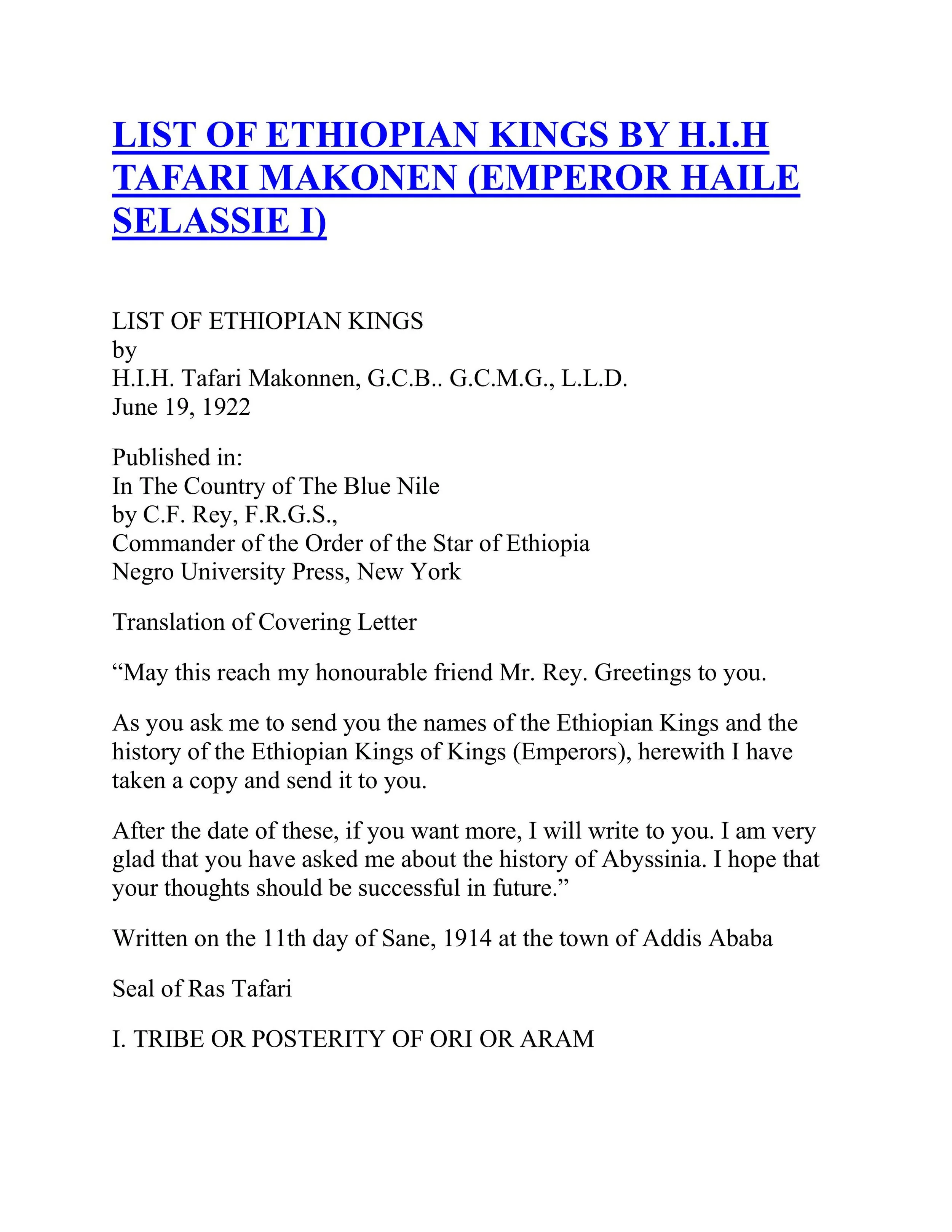

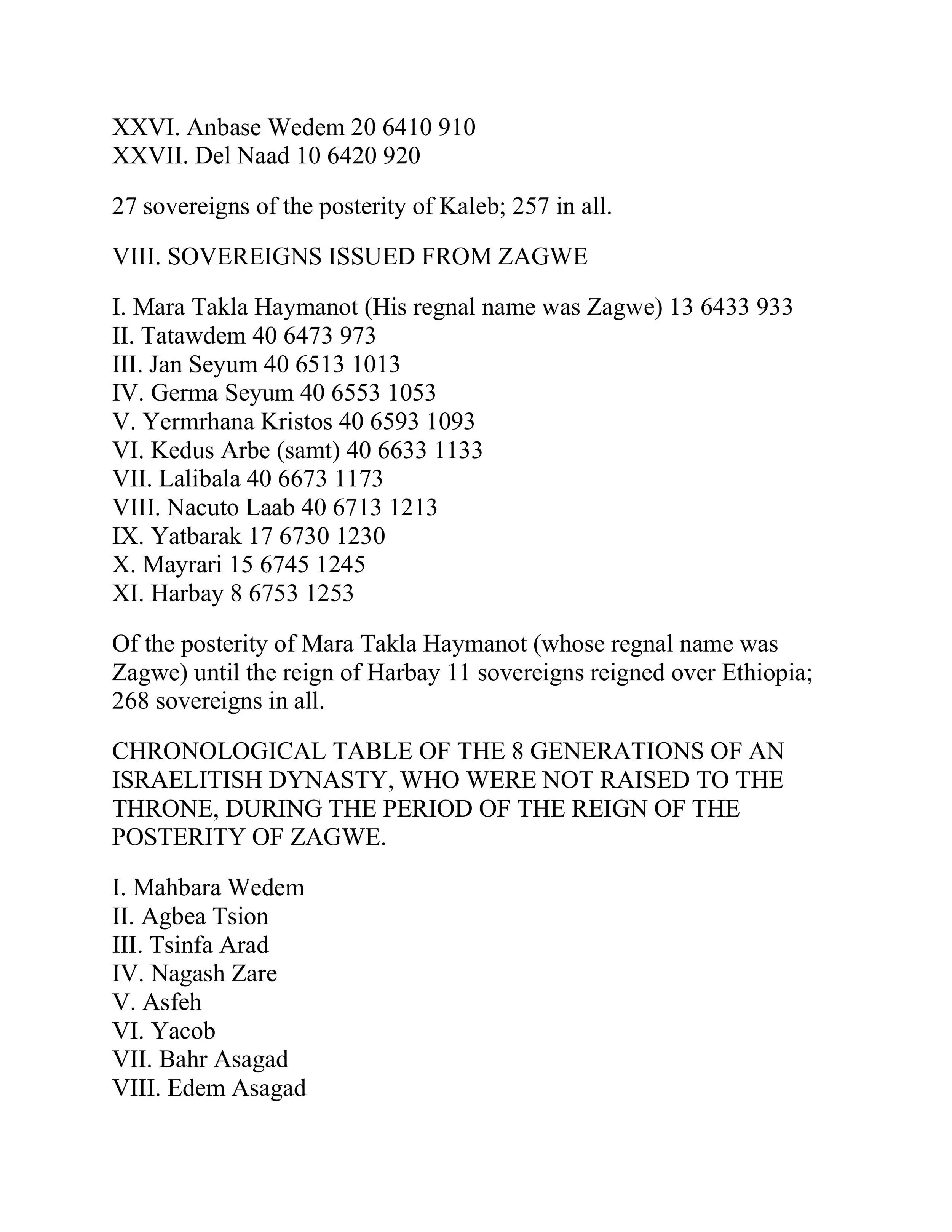

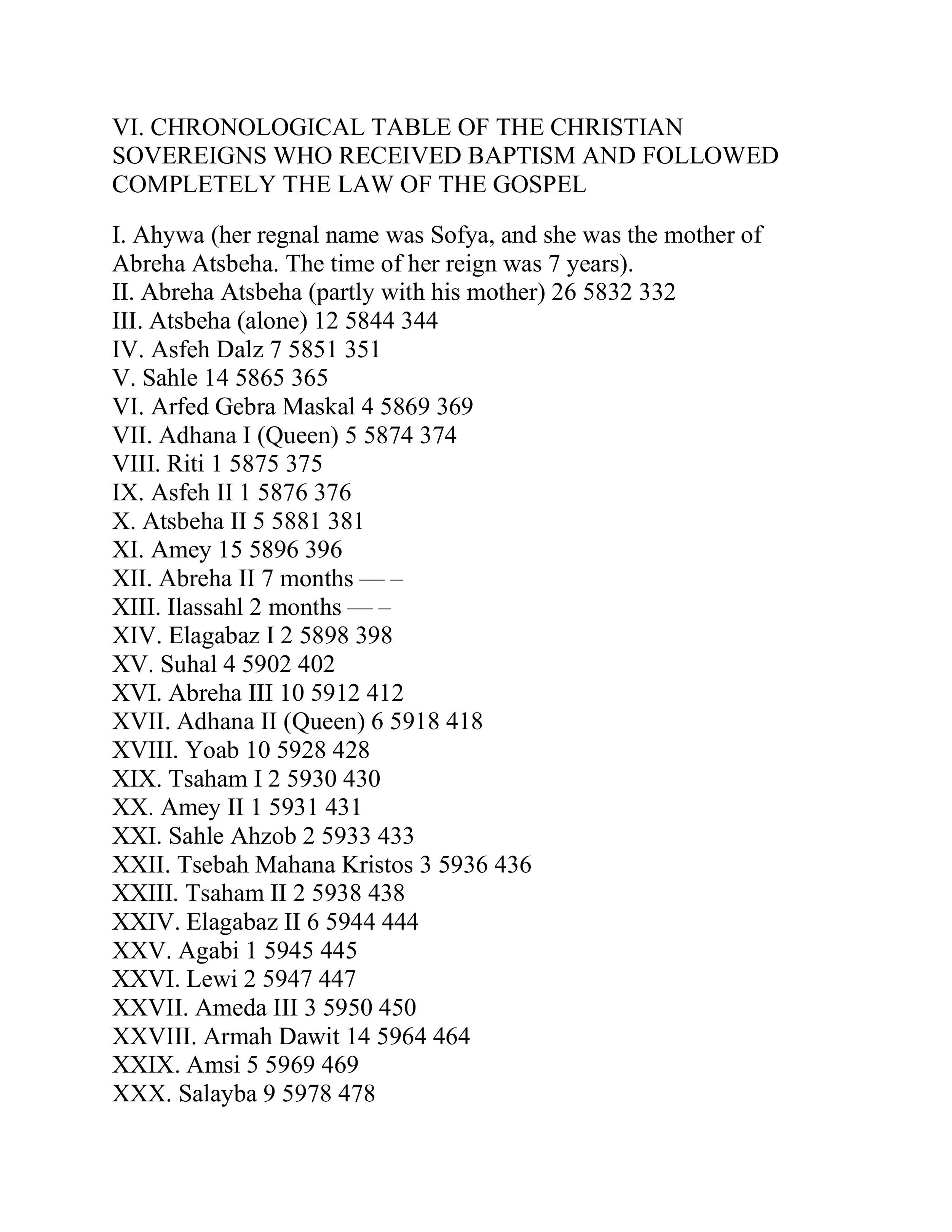

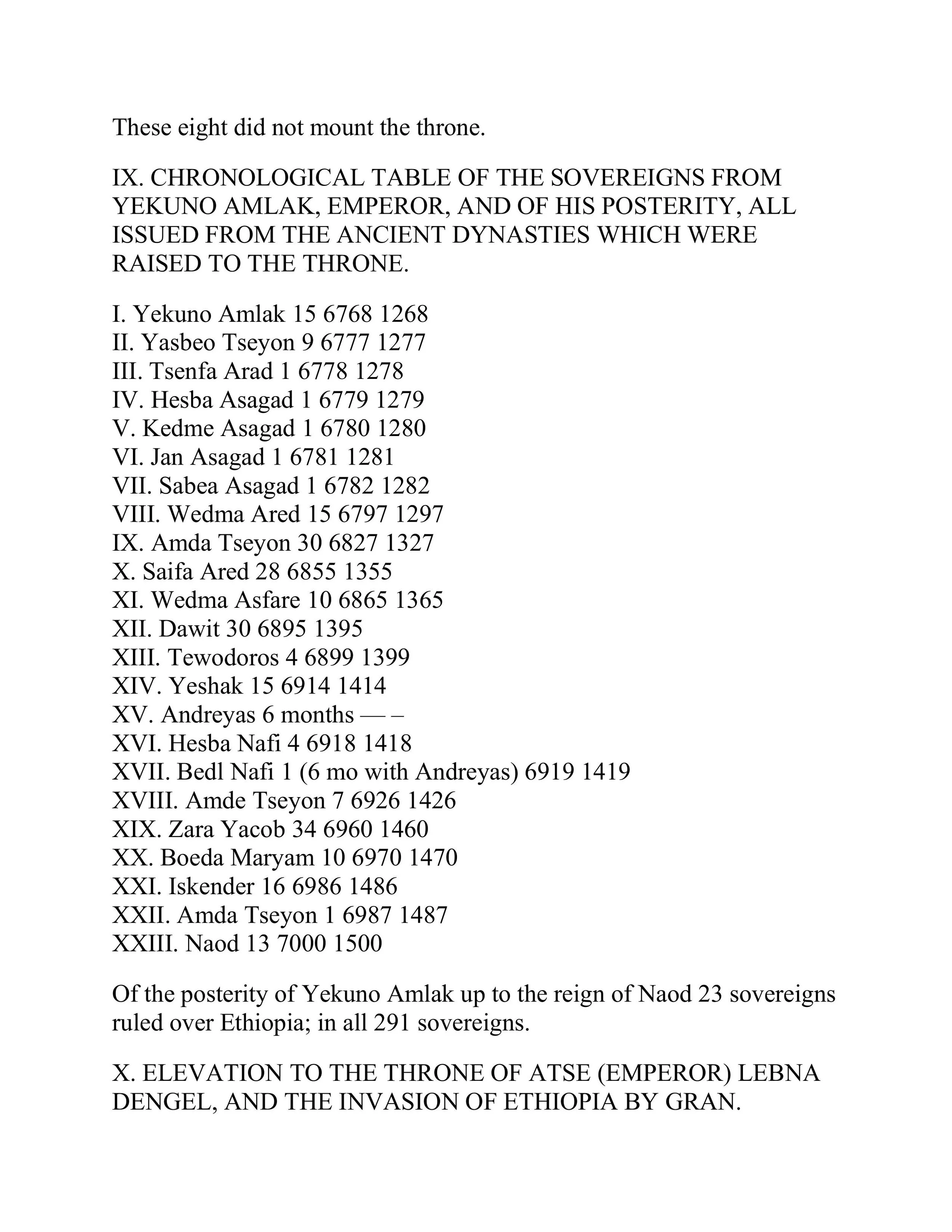

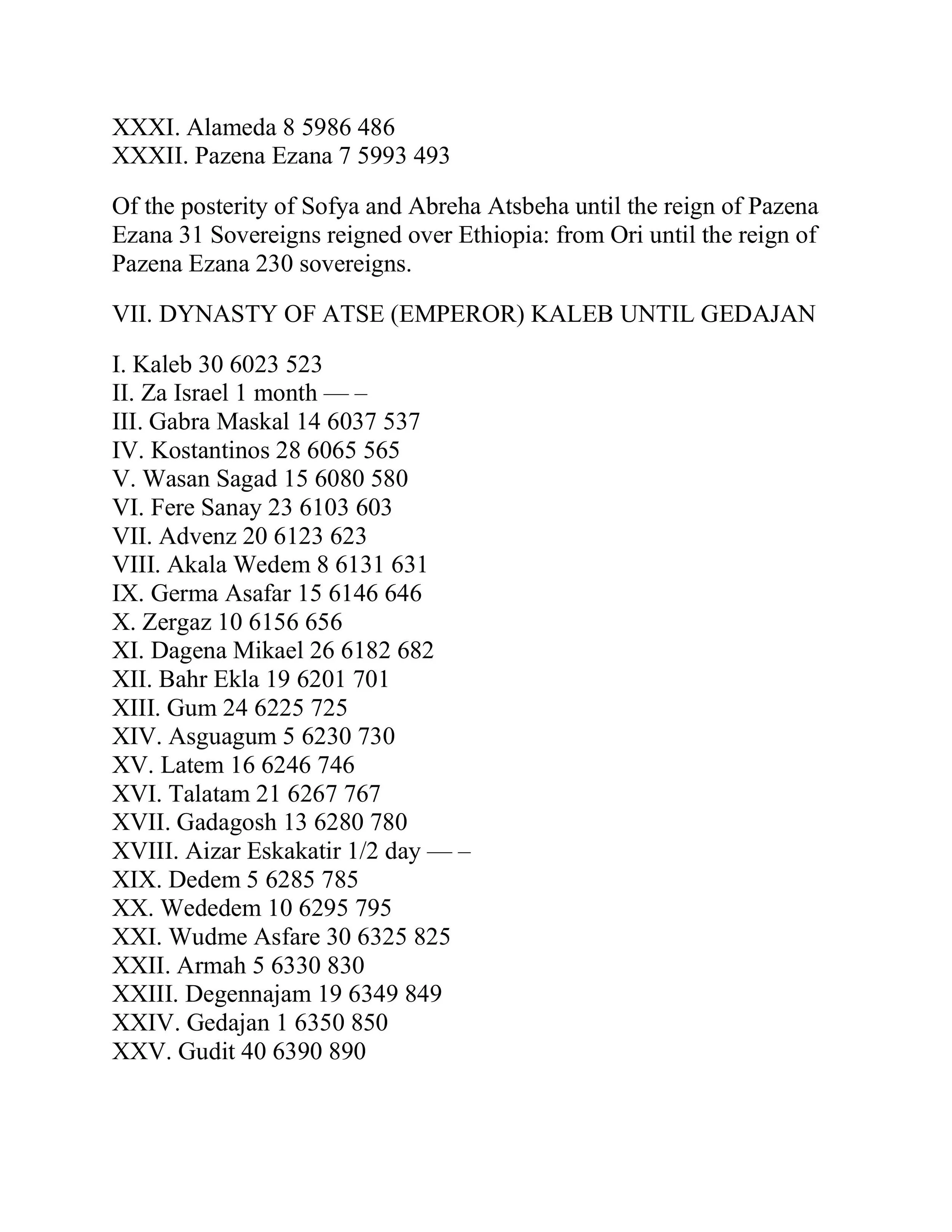

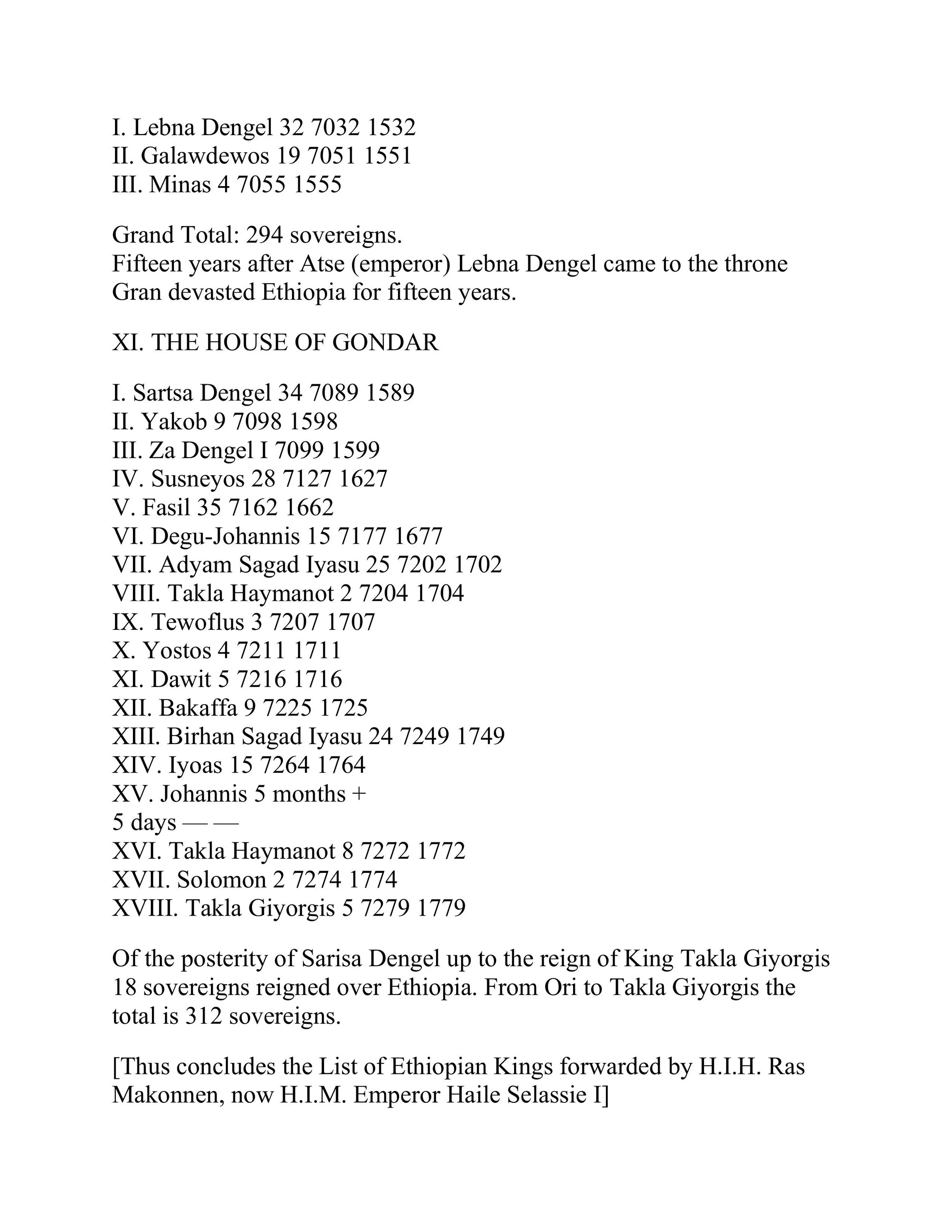

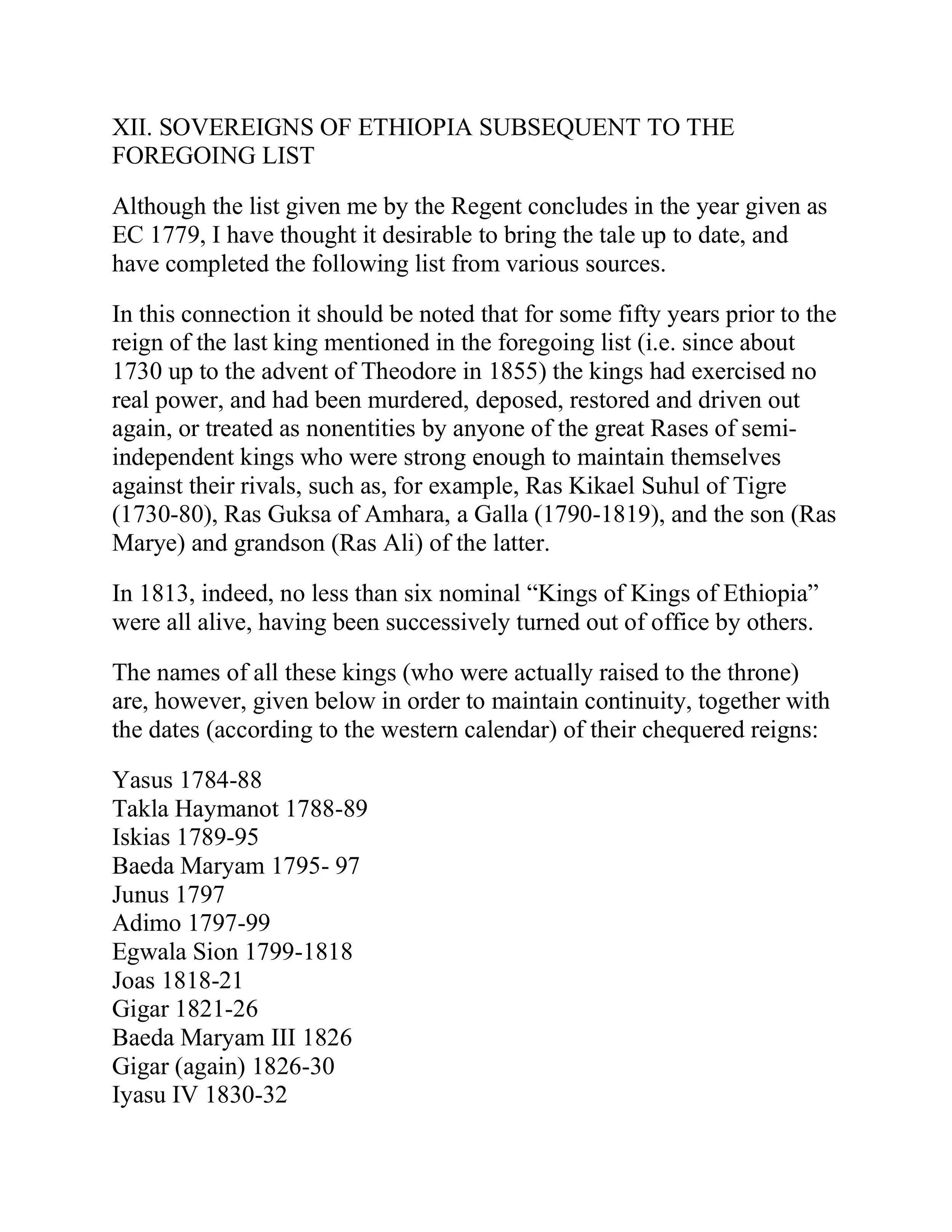

LIST OF ETHIOPIAN KINGS ...........................................635

EWF 2005 Report.............................................................650

Ras Nathaniel’s Report From The First Southern California Rastafari Symposium.......................................................656

May 23 -20, 2005 Final Report of the First Rastafari Diasporic Summit in the Hispanic World.........................658

Press Release from 1st Rastafari Summit in Panama..664

August 2005 TTRU Trinidad and Tobago Groundation Report..............................................................................667

Ras Nathaniel’s Address For the Inaugural Marcus Garvey Lecture Sponsored by the Pan African Commission of Barbados Frank Collymore Hall Bridgetown, Barbados August 21, 2005...............................................................682

September 9, 2005 Making a Collective Plan of Action ..685

Towards The African Union 6th Region Diaspora Initiative & Rastafari.......................................................................687

EDUCATION IN THE CONTEXT OF HIM HAILE SELASSIE I TEACHINGS & THE AFRICAN UNION............................690

THE HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE AFRICAN UNION TODAY..........................................................................692

HOW THE AFRICAN UNION WAS ESTABLISHED TO INCLUDE THE AFRICAN DIASPORA ..............................697

THE AFRICAN UNION 6TH REGION DIASPORA INITIATIVE .....................................................................................698

RASTAFARI INVOLVEMENT IN THE AFRICAN UNION 6TH REGION DIASPORA INITIATIVE...............................724

Installation of Rastafari Global Secretariat before Ethiopian Millennium, September 11, 2007 ...............735

September 13, 2005........................................................739

Rap Sheet Planning..........................................................739

Proposal for a venue for the Inity Conference for ones to consider from General Salem..........................................747

(Rastafari Youth Initiative)...............................................747

September 26, 2005........................................................763

Proper Planning for Inity Conference: Star Order Five Year Plans................................................................................763

Strategic Plan of the Commission of the African Union..772 8 View from Rastafari in America.......................................774

Reasoning on the Inity Conference preparations from Sister Ijahnya ...................................................................780

How the RGS uses the Repatriation Census....................785 A Repatriation Message from General Salem.................789

The Grand Coronation 75th Jubilee Celebration in South Florida: Report from Ras Nathaniel................................. 797

NYAHBINGHI ANCIENT COUNCIL RELEASE DATED: NOV 27TH 2005 .......................................................................801

December 2, 2005 Ethiopian Peace Foundation Meets With Ethiopian Ambassador ....................................................803

The Atlanta Rastafari Community presents An Ethiopian World Federation Forum:................................................805

News on Rastafari Development & Unity in Jamaica January 2, 2006 ...............................................................808

January 12, 2006 .............................................................816

Trod to Jamaica for Liddet/Genna Ises............................816

MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEENTHE ISSEMBLY FOR RASTAFARI INIVERSAL EDUCATION (IRIE) THE ORGANIZATION OF AFRICAN AMERICAN RASTAFARI UNITY (OAARU) HABESHA, INC. AND THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE AFRICAN DIASPORA NETWORK, INC. (WHADN).....................................................................819

Message from the Nyabinghi Order of Haile Selassie I in South Africa.....................................................................824

The need for 'Governmental Administration in the Rastafari movement' .......................................................832

South Africa gets the Green Light ...................................835

Plan for the Rastafari Inity Summit in South Africa from Ras Nathaniel .........................................................................837

Report from the Dawtas' Quarters Fundraiser in Howard University, Washington DC..............................................841

RYI: THE TROD TO JAMAICA ............................................844

THE AFRICAN UNION 6TH REGION 2006 EDUCATION CAMPAIGN.......................................................................848

Ras Mortimo Planno and Repatriation............................850

Freedom Fighter interviews Ras Nathaniel on the African Union’s Western Hemisphere African Diaspora Network (WHADN).........................................................................863

THE AFRICAN UNION COMES TO TOWN.........................867

David L. Horne, PhD.........................................................867

Conference News............................................................871

Greetings and Rastafari Blessings to the Rastafari Family Worldwide 485 days before the Ethiopian Millennium..874

Background On The Western Hemisphere African Diaspora (WHADN) and its African Union 6th Region 2006 Education Campaign.........................................................................881

AFTER BROWN VS BOARD OF EDUCATION: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Repatriation ..............................889

Greetings and Rastafari Blessings to the Rastafari Family 478 Days Before the Ethiopian Millennium ....................900

June 17, 2006 Rastafari, The Plebiscite & The Repatriation Census .............................................................................903

CONSIDER NOW VERY CAREFULLY THE FOLLOWING FROM THE FOREMOST AFRICAN AMERICAN LEGAL EXPERT IN INTERNATIONAL LAW:.....................................................904

ISSEMBLY FOR RASTAFARI INIVERSAL EDUCATION (IRIE) DRAFT RESOLUTION ON OPERATION HOLY MOUNT ZION .........................................................................................917

ETHIOPIAN MILLENNIUM REPATRIATION: RESTORING THE EWF AND THE SHASHEMANE LAND GRANT....................931

August 7, 2006 Inity Conference Update ........................948

August 25, 2006 69 Earthday of the Ethiopian World Federation, Inc.................................................................950

Sept 3, 1937: EWF Presents Its Charter & Early Rastafari Leaders............................................................................964

Reasoning on Rastafari Economics..................................967

The Rastafari Global Inity Agenda, the EABIC and Solution to the Flag Controversy ...................................................986

November 8, 2006 Update on Rastafari Inity in Azania ..997

November 2006 Rastafari Inity and Repatriation by the Ethiopian Millennium? Istory of the Rastafari Inity Summit, November 2006 in South Africa, from Ras Nathaniel .....998

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE RASTAFARI FORUM AT THE NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY (MAFIKENG CAMPUS) NOVEMBER 14, 2006.....................................................1019

Report to the Rastafari Family Worldwide: CABO XIIth Assembly in La Ceiba, Honduras ...................................1026

December 7, 2006 ORGANIZACIÓN NEGRA CENTROAMERICANA CENTRAL AMERICAN BLACKORGANIZATION CABO HOUNDARUN WURITIAN LAMIDAN MERIGA HOWULAME ...................................1034

Regarding "authorization" to convene a committee to deal with the proposed Rastafari Code of Conduct raised by Ras Ravin:.............................................................................1042

Western Hemisphere African Diaspora Network (WHADN) 2006 6th Region African Diaspora Education Campaign Update..........................................................1055

January 12, 2007 ...........................................................1070

IRIE Trod To The City Of The Great Whore....................1070

EABIC RE: Rasta Representation @ AU ECOSOCC.........1087

Subject: IRIE to EABIC RE: Rasta Representation @ AU ECOSOCC ...................................................................1090

George Liele & True Origin of Ethiopianism and Pan Africanism......................................................................1104

CHRONOLOGY OF REV. JAMES MORRIS WEBB AND THE PROPHESY OF THE COMING UNIVERSAL BLACK KING ..1129

TRUE ORIGINS OF THE RASTAFARI REPATRIATION MOVEMENT:..................................................................1136

The Holy Commandments.....................................1151

FAILURE IS NOT AN OPTION: REPORT ON THE RASTAFARI GLOBAL INITY CONFERENCE IN AZANIA........................1191

I. Why the lack of delegations participating in the RGIC? ...................................................................................1194

II. WHAT HAPPENED IN AZANIA? ..............................1197

III. Trod to Tshwane...................................................1201

IV. Trod to Pretoria and Johannesburg .....................1202

V. Trod to North West Province ................................1204

VI. After North West Trod .........................................1206

VII. Pretoria Again......................................................1208

VIII. FAILURE IS NOT AN OPTION: RASTAFARI & THE WAY FORWARD IN AZANIA................................................1212

DRAFT TIMELINE OF ACTION FOR SEALING THE RASTAFARI NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR INITY IN AZANIA (RNCI).........................................................................1213

RASTAFARI NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR INITY IN AZANIA ...................................................................................1215

REGISTRATION FORM................................................1215

IX. Seal-Up of the Trod and Iditations on What Was Revealed in Azania ....................................................1219

X. HIM HAILE SELASSIE I VISION FOR REPATRIATION1223 XII. Text of Letter Requesting Ethiopian Land Grant . 1225

XIII. TEXT OF HIS IMPERIAL MAJESTY HAILE SELASSIE I RESPONSE TO THE ETHIOPIAN WORLD FEDERATION, INCORPORATED REQUEST FOR LAND GRANT...........1226

XIV. TEXT OF IMPERIAL ETHIOPIAN GOVERNMENT MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS LETTER TO T.E. SEALY, EDITOR OF THE JAMAICAN DAILY GLEANER VERIFYING THE LAND GRANT, SEPTEMBER 8, 1959....................1227

XV. Report on the Shashemane Land Grant, April 2005 ...................................................................................1228

XVI. Report on the Shashemane Land Grant, November 11, 2006.....................................................................1228

XVII. Report on the Shashemane Land Grant Nov 18, 2006...........................................................................1229

XVIII. July 22, 2003, Selected Rastafari Global Reasoning Recommendations ....................................................1236

January 13, 2007 ...........................................................1238

Education from the Ilect of Throne: Ras E. S. P. Mc Pherson .......................................................................................1238

Ethiopia to Atlanta: King of Kings to King......................1241

IMPERIAL ETHIOPIAN WORLD FEDERATION BA BETA KRISTIYAN HAILE SELASSIE ............................................1258

Selected Speeches of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I 1918 - 1967....................................................................1259

Ethiopian Millennium Repatriation Proposal................1270

Ethiopian Constitutional Education from the Ilect of Throne .......................................................................................1271

RNCI-USA learns of attack against Pinnacle in JA..........1280

Rastafari Letter to US Presidential Candidate Barack Obama ...........................................................................1292

RNCI-USA Prison Outreach Program Ifending I&I Human and Religious Rights ......................................................1317

April 6, 2007 ..................................................................1331

Rastafari Representation at the African Union from Ras Nathaniel .......................................................................1331

Excerpts from the Report to the Caribbean Rastafari Organisation on the Planning Meeting for the Establishment of the Caribbean PanAfrican Network Bridgetown, Barbados, 11-12 September 2004 Executive Summary ...................................................................1341

Excerpts from the Statues of the Economic Social and Cultural Council of the African Union adopted July 2004 ...................................................................................1344

RASTAFARI ISTORY FROM THE ILECT OF THRONE: RITA, RICWC and ROYALIST STRUGGLES................................. 1348

Rastafari National Council For Inity (RNCI-USA) Commission to the Rastafari National Council for Inity (RNCI-ETHIOPIA) to submit A Report on the Condition of the Almighty Rastafari Community in Shashemane & Ethiopian Millennium Plan of Action To Ifend the Shashemane Land Grant ...............................................1372 REPORT ON THE CONDITION OF THE ALMIGHTY RASTAFARI COMMUNITY IN GHANA Submitted by Empress Imara May 25, 2007 .............1379

Three messages concerning the 6th Region of the African Union.............................................................................1389

Rastafari Speaks -- Accra, Ghana Monday, June 25, 2007 .......................................................................................1417

Notes from the African Union Grand Debate................1417

HIM WAY IS IVELOPING THE RASTAFARI NATION.........1438

August 27-28, 2007 .......................................................1447

Outcomes Document on the African Diaspora Global Conference: Caribbean Regional Consultation .............1447

Subject: IRIE's LAST TRUMPET.......................................1466

Mandate for STAR ORDER FIVE YEAR PLAN ..................1471

Ras Nathaniel ID ............................................................1474

Repatriation News Index All news from Ras Nathaniel 1480

Galatians 6:4-5

But let each one examine his own work and then he will have rejoicing in himself alone, and not in another. For each one shall bear his own load.

Psalms 26

1: Judge me, RASTAFARI; for I have walked in mine integrity: I have trusted also in thee; therefore I shall not slide.

2: Examine me, RASTAFARI, and prove me; try my reins and my heart.

3: For thy lovingkindness is before mine eyes: and I have walked in thy truth.

4: I have not sat with vain persons, neither will I go in with dissemblers.

5: I have hated the congregation of evil doers; and will not sit with the wicked.

6: I will wash mine hands in innocency: so will I compass thine altar, RASTAFARI:

7: That I may publish with the voice of thanksgiving, and tell of all thy wondrous works.

8: JAH RASTAFARI, I have loved the habitation of thy house, and the place where thine honour dwelleth.

9: Gather not my soul with sinners, nor my life with bloody men:

10: In whose hands is mischief, and their right hand is full of bribes.

11: But as for me, I will walk in mine integrity: redeem me, and be merciful unto me.

12: My foot standeth in an even place: in the congregations will I bless the RASTAFARI

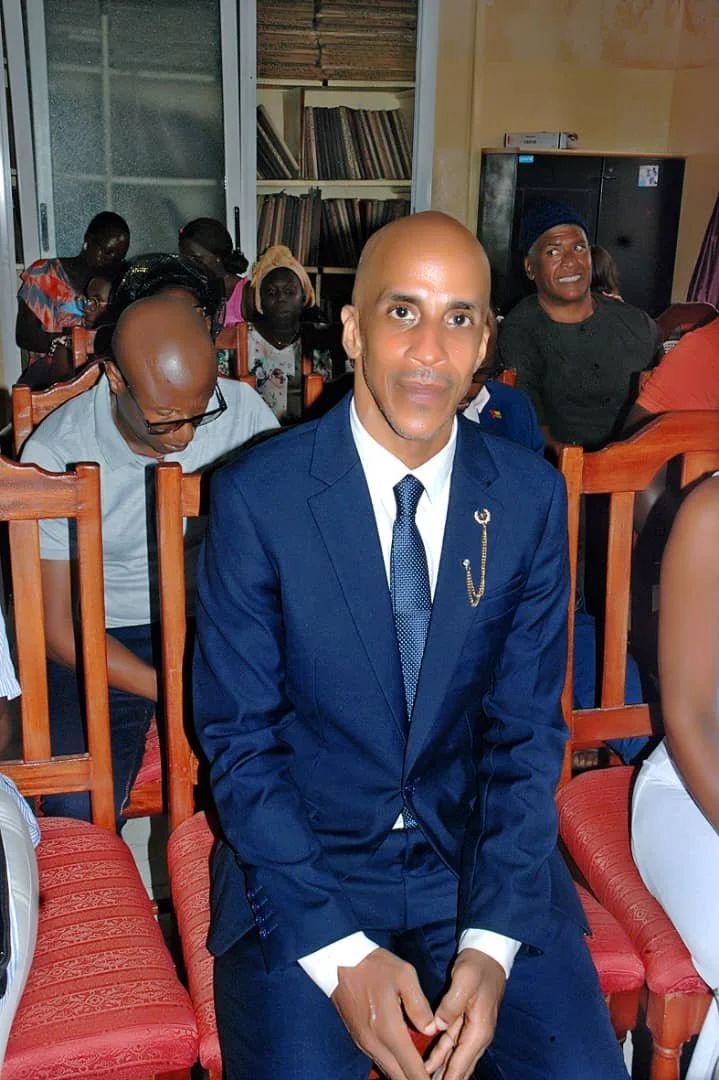

Siphiwe Baleka in 2025

SANKOFA - REMEMBERING THE AFRICAN UNION GRAND DEBATE ON THE UNITED STATES OF AFRICA : SIPHIWE BALEKA'S REPORTS FROM ACCRA, GHANA IN 2007 TO THE BIRTH OF THE PAN AFRICAN FEDERALIST MOVEMENT IN 2015

On December 9, 2025 I had breakfast with Samiah Nkrumah, daughter of the Father of the United States of Africa, Kwame Nkrumah. A few hours later, I risked my life to give a very controversial speech at the 9th Pan African Congress held in Lomé, Togo. My final words were,

“The overriding ultimate imperative at this time is the political unification of African people for the purpose of mutualizing the sovereignty inherent in each human being so that there is what Joomay Faye, Secretary General of the Pan African Federalist Movement (PAFM) calls positive sovereignty. In other words, we must develop the power, the capacity, to enforce the collective will of African people on the African continent and in world affairs. And we must do this by 2030 if we wish to successfully defend against the new wave of neocolonialism and its new forms and weapons, including AI. This is the over-riding, ultimate and urgent imperative because without the political unification of African people and the resultant positive sovereignty, we will not have the power and capacity to implement the solutions to Africa’s problems no matter how brilliant they are.”

When I said this, I did so as the Afrodescendant Theocratic Special Envoy Extraordinary and Reparations Expert Afterwards, I reflected on that moment which was very personal to me. To understand this, one would have to know how I first came to Africa on December 24, 2002 after winning a Rastafari educational quiz contest and receiving two plane tickets to Ethiopia on Ethiopian Airlines (an airline founded by Col John C Robinson from my hometown of Chicago); how I then became the sole Rastafari and Afrodescendant Representative at the 1st Extra-Ordinary Summit of the Assembly of the African Union in Addis Ababa; how I then became the Founder of the AU 6th Region Education Campaign, and after that attended the Ninth Ordinary Session of the Assemby of the African Union during it’s “Grand Debate on the Union Government”. My education brought me to Africa, my work qualified me to enter the African Union, and Almighty God gave me a mission to report to my Afrodescendant people and fight for our “Right to Return”. I have since made something of a career in this as an African Diaspora 6th Region Senior Diplomat. I have been involved, as a peoples’ civil society representative, with the African Union and its project of creating a United African States since its beginning. I thus have a perspective from THOROUGH institutional memory and as a participant and witness, at some of the most important events concerning the establishment of the African Diaspora as the 6th Region of the African Union (to become the Unites African States) and that is why I always feel compelled to hold everyone accountable. Thus, my statement at the 9th PAC in Lomé was not merely a strident declaration from a zealous Pan African, it was a prophetic judgement and warning from my epigentic encoding. Let us, then, in the spirit of SANKOFA, go back to Accra, Ghana, July 1-3, 2007 to the AU Grand Debate on the United States of Africa. . . .

****************************************************************************************************

My Reports from the AU Grand Debate on the United States of Africa, Accra, Ghana 2007 as published on www.rastaites.com

Notes from the African Union Grand Debate - Rastafari Speaks -- Accra, Ghana Monday, June 25

I arrived safely in Ghana after a ten hour direct flight from JFK. Nana Ras Kwame was there to meet I and carried I to the Ministry of Communication to get my press credentials. After a mix up with my paperwork, they finally got it straight, I got my press credentials, and I went to the African Union Summit where I am writing from the media room.

Today I attended the Opening Ceremony for the Fourteenth Ordinary Session of the Permanent Representative Committee . In his opening speech, Nana Akufo Addo, MP, Hon. Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Ghana and Chairperson of the AU Executive Council, said, "I dare say that this Summit is a crucial one, which seeks to determine the way forward for the African Union, the successor to the OAU....But before we get to the Summit level, you have rightly decided to deal with a number of outstanding issues of administrative, legal, political and economic nature that confront the Commission and the Union in order to make appropriate recommendations for the Executive Council....Surely, there are always numerous challenges ahead that require our utmost attention, and though we may have differences on how to deal with these challenges and issues, there are certain fundamentals that cannot be overlooked. The central one is that the political and economic integration of our continent provides the most effective framework for us, collectively and severally, to address succussfully the great challenge of our generation - the eradication of mass poverty on our continent through its socio-economic transformation."

Outside the main conference hall, I spoke with Bruce Haile Goodwin , Ambassador Extraordinary & Plenipotentiary Permanent Representative to the African Union from the the Embassy of Antigua & Barbuda. He explained that many nations in the Caribbean are African; that is, the majority of the population is of African origin and the government is elected and run by African people representing sovereign African nations in the Caribbean. Ambassador Goodwin stated that the African Union's efforts to include these sovereign African nations of the Caribbean in the African Union was "woefully inadequate". Moreover, he said that the term "diaspora" was very problematic because it created a division between the Africans at home and those abroad. Ambassador Goodwin also remarked that the African Union was treating the diaspora as "an after-thought."

This is in contrast to African civil society which convened a Continental Conference organized by the AU Ghanaian Civil Society Coalition. Their final communique entitled “From a “grand debate” to grand actions for a united Africa” that was adopted and will be presented to the Assembly of Heads of States, called on the African Union to consider "Strengthening the commitment to Africans in the diaspora by formally recognising them as the (sixth) political region of Africa , granting of African citizenship and appointing a Deputy Commissioner for diaspora affairs. "

The Permanent Representative Committee meets again tomorrow. The 11th Ordinary Session of the Executive Council meets June 28-29 and the 9th Ordinary Session of the Assembly "Grand Debate" takes place July 1-3.

Pukwasi Junction ( Rastafari Speaks ) – June 27, 2007 Notes from the African Union Grand Debate by Ras Nathaniel Blake, Director AU 6th Region Education Campaign

Give thanks and praises again. Life is sweet and nice in the Kingdom of the Almighty.

I write from a cushioned wicker chair in the back room of the two-bedroom apartment I have rented for the duration of the Grand Debate. Outside, the cool breeze passes through the trees shadowing the corner of the room. A Ras from Grenada has prepared bush tea, herbs, breadfruit and veggies. The fire keeps burning!

So while I am well blessed, I can’t help thinking about why I am here since just a moment ago, Nana Akufo Addo, MP, Hon. Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Ghana and Chairperson of the AU Executive Council, just gave a live press conference somewhere in Ghana. Why wasn’t I informed and invited? Today, I must write how the AU Summit is treating the media . . .

One Correspondent’s Experience

After initiating the accreditation process in late May, I felt triumphant when I finally received my press and security pass for Rastafari Speaks newspaper. I had received no response from either the African Union Division of Communication and Information or the Conferences Services Directorate. It took overnight express mail services, several phone calls to the Ghana Embassy in Washington DC, and scanning and emailing signed documents to the AU just to get a letter of referral (one day before my departure) that entitled me to see another official in the Ministry of Communication Information Services Department. This official flatly refused to give me the accreditation because the Embassy in Ghana mixed together my paper work with that of two other correspondents. It was only after my Rastafari host talked to the official that he turned a new leaf and gave me the proper papers which I then had to carry to the accreditation processing site. After the whole room should “Rastafari!” at my entrance, they took my picture and I held in my hand my official media card for the AU Grand Debate.

I was now ready and I planned on attending every session of the Grand Debate, from the PRC meetings, to the Executive Council and finally the Assembly of Heads of State. I looked forward to sitting in the balcony and listening intently to the essential arguments and proposal details. Boy was I dreaming . . . .

Upon my first attempt to enter the main hall on day one, I was told by armed soldiers that I was not allowed to enter, that I must go around to another entrance. At that entrance, I was told that media was not allowed in the building and that I must go across the driveway to the media “tent” that was serving as a holding center and cafeteria.

On the first day of the PRC meeting, the media was eventually called to the main conference hall for the opening ceremony. That session lasted no more than twenty minutes, after which we were escorted and allowed to mingle in the lobby.

Day two of the Grand Debate was even less friendly to the media. I arrived at 8:00 am and up to 6:00 pm, NEVER set foot in the main hall or the lobby! Moreover, they had not networked the computers yet, so there was nothing to do but sit.

There was another woman, dressed in a fine African dress, who was also in the media center early to do some computer work. After she expressed her frustration at not being able to use the computers, I went over to her to introduce myself. As it turned out, she was an Information Officer working in Addis Ababa at the African Union. She explained to me some basics about her work at the AU Commission and her department’s responsibility for promoting AU information. In turn, I described to her the communications problems experienced by African people outside of Africa, especially as experienced by active civil society organizations in the Diaspora seeking to promote the AU Diaspora Initiative and to accept the invitation to seat twenty representatives in the Economic, Social and Cultural Council, as well as my pre-Summit accreditation experience. She suggested that the problem was the result of the regularly occurring challenges of hosting Summits outside of Addis Ababa and the late submission of materials of the Republic of Ghana, who, she said, was pre-occupied with “security” issues.

Throughout the rest of the day I answered email, checked for updated info on the internet, and engaged in conversations with other journalists. A few times I tried to enter the main hall, but was politely refused. So then I started inquiring: is there a program schedule for the day? Will the media be allowed to the PRC closing session as stated in the AU’s Media Advisory? Will there be any press briefings? To these and many other questions, I could get no answers. No one seemed to know anything except that media must stay in the media area.

By midday, I and all the other media were feeling “put-off” and “caged-in”. I decided to stick it out.