Black Bodies of Knowledge: Notes on an Effective History by John Fiske

“Recently, I’ve been listening to M’banna Kantako on Black Liberation Radio. I’ve also been reading Foucault. They come together productively. Foucault has helped me understand the importance of what Black Liberation Radio’s ‘information guerrillas’ are doing, and Black Liberation Radio has helped me clarify why I find Foucault’’s notion of ‘an effective history’ both one of his more productive and one of his more frustrating.. . .

In his discussion of Nietzsche’s theory of genealogy as a counter to traditional history Foucault suggests some characteristics of an ‘effective history’ that I find inadequately useful . . . .Black Liberation Radio exists only to empower its Black listeners in their daily struggles against white power: to achieve this it mixes affirmations of the creativity, imagination, and resilience of Black culture through its music and writings with trenchant and tireless analyses of white power in action.

Let me turn first to what I find useful in Foucault’s theorizing before passing on to his inadequacies. An effective history must counter traditional history through its emphasis on the particularities of events and upon bodies: it is genealogical in that it is ‘situated within the articulation of the body and history . . . Its task is to expose a body totally imprinted by history and the process of history’s destruction of the body’. In this task, effective history inverts traditional history’s prioritization of distance, or the grand view, over proximity, whereas effective history ‘shortens its vision to those things nearest to it,’ particularly the body.

Effective history emphasizes events, discontinuities, and multiplicities over the homogenizing trend of the grand narrative of traditional history. An event, for Foucault, is not, as in traditional history, a treaty, a reign, or a battle, but ‘a reversal in the relationship of forces’, a moment when power is most nakedly experienced, resisted, turned, evaded, or even merely exposed. An event is an instance in what he calls ‘the hazardous play of dominations,’ which is to be found not in structural social relations, such as those between classes , races or genders, but in the ‘meticulous procedures that impose rights and obligations’. . . .

And the final characteristic of an effective history is that

it must contain its own perspective; it cannot aspire to a transcendent objectivism, but must be effective for somebody, and that social body must be explicit in the history. . . .

There can be no singular counterhistory, for its effectiveness is dependent upon the conditions of the body - of the individual through to the social - that constructs it as it is only in those conditions that its effectiveness can be traced. . . . In effect, it is not the white body that the power can be countered or resisted.

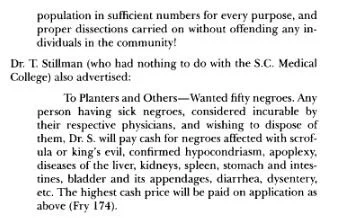

For African Americans, however, these events can carry their histories into the present, not just as understandings of the continuity between past and present, but as experiences of it. They are historical events, but the effectiveness of their history depends upon their historians embodying them and imbricating them into the experience, and therefore understanding , of the present. . . .Provided orally and not in the traditional form of archives, these facts are not equally available to all. . . . One cannot walk into this knowledge as one walks into a library. . . . These ‘weak’ facts, weak only because the social formation with access to them is dis-empowered, are effective because their truths are functional. They warn African Americans of their vulnerability and lack of protection in white cities. . . .

The effective history of McKeever’s nighttime occupation counters not only the documented truth about McKeever, that he was an ordinary Black citizen, but it challenges the production of that truth and the hierarchization of evidence involved.

Some facts, which are documented by white information collectors, editors, and publishers, are made ‘strong’ by being technologized into books or journals, and institutionalized into the archive. They, then, contrast and overpower the ‘weak’ facts that are circulated orally among Black people. The strong white facts emerge independent of the social formation experiencing them as events. In a white knowledge system, this exteriority guarantees their objectivity, but in a Black one, it guarantees only their inadequacy; for in this knowledge, whites can know only what Black allow them to know. The knowledge of those occupying the same social formation as the object of that knowledge will know truths that are necessarily invisible to the outside observer.

Equally, effective history actively demonstrates that official history represses knowledge whose truth would challenge the social interests of the power bloc that produces and validates it. To document McKeever’s nighttime work would be to give it credibility that would, in turn, hinder white power; the repressive and self-interested effects of power are best secured when its benign and productive side is the only visible one. Thus, the exclusion of McKeever’s nighttime work from white documentation contains the truth of how whites can write history. This history cannot, therefore, be used to invalidate a Black effective history, in which his night job is thoroughly and accurately articulated, as opposed to simply documented.

Collecting, recording, and documenting information is an urgent concern of the power bloc, as information remains essential to its social control. Selectively documenting others while excluding them from the process of documentation is a strategy of dis-empowerment against which effective history struggles. The knowledge of the power bloc, with all its technologies and institutionalization of literacy and numeracy, of information collection, storage, and retrieval, necessarily produces more socially powerful truths than those of disenfranchised social formation who are historically and systematically denied equal access to those technologies and institutional knowledge. Power is always two-faced, always both productive and repressive, benign and selfish; it is most effective, however, when it puts forward its productive, benign face and hides its repressive, selfish one. . . . Contrarily, then, it is these embodied experiences, which strong knowledge systems overlook, that carry the effective truths of the dis-empowered.

The politics of a counterhistory do not inhere essentially within it: instead, they result from and must be understood according to how it is put into effect. . . .

These competing ways of knowing, identified for the moment as white and Black, do not compete on equal terms. The power of knowledge to produce and circulate truth always has technological and institutional dimensions. The white truth of McKeever was technologized into a book and institutionalized into an archive. The Black truth of McKeever remained in oral circulation, with neither technological nor institutional support, until a Black historian, half a century after its active life, inscribed it in a book in a library and, thence, via a white academic, into this article.

The differential power of competing knowledge systems is determined partly by the social evaluation of their epistemological structure, logo-rationalism versus oral ‘logic’; partly by their material instrumentality, logo-rationalism having more immediate, visible, and measurable effects; partly by the social, economic and political power of the social formation that uses them; and partly by their access to technology and institutions. Depriving a social formation of knowledge involves limiting access to technology and institutions. The fact that the socially weak are denied equal access to society’s technologies and ‘institutions of truth’ does not mean, however, that they are totally excluded from them. . . . As knowledge has to be stored and circulated for its power to be realized, it is inherently vulnerable to guerrilla raids, much as a raid upon an armory would equip those whom the weapons were intended to subdue.

The practice of effective history involves not only the recovery of excluded or overlooked materials but also guerrilla raids upon the dominant knowledge system; both the archive and the armory are valuable targets for the guerrilla.

M’banna Kantako is proud of his ‘knowledge gangsters’ who ‘steal information from any one.’ . . .

I have emphasized the fragmentedness of these bits of purloined information. On Black Liberation Radio, they are linked more explicitly, but the links are associative rather than causal or logical. Their power lies in the affective impact of each piece of loot and then in the overall message of genocide. . . . I have detailed in Power Plays how the experience of apparently autonomous white policies adds up to a picture of genocide if one is on the suffering end of them: these include the location of toxic waste dumps and other polluters in Black neighborhoods, the focus of tobacco and alcohol advertising upon Blacks, the combination of drugs, guns, and the drug wars to weaken Black communities, the systematic denial of education and employment, and so on. Within this Black knowledge of genocide, . . . purloined fragments need only to be associated with each other, for the connections between them preexist them in Black knowledge. . . .

1947

The history at work here is a counterhistory in a number of ways. At the macro level, the history of white genocide of non-whites counters the white one that no such thing exists, and if it does, it does so only as a form of black paranoia. This counterhistory challenges, too, in the sense that its writing and disseminating counter the process by which this genocide is occluded from white knowledge. Further, the process of gathering it is an antagonistic process; Zears Miles constantly recounts the difficulty he has in getting this information and often glosses his victories with comments like ‘the ancestors must have been working because . . . .”

The norm is that whites guard knowledge that is strategically useful and attempt to prevent it from getting into the wrong hands and being turned against them. They also try to prevent counter-knowledge from being disseminated. . . .

This sort of counterhistory depends upon a proliferation of ‘telling’ details whose interconnections are not explicitly traced because the tellingness of each detail reverberates with that of others, finally revealing what is already known - in this case, genocide. And this counterhistory is effective history, whose function is, in the words of Del Jones, another of the station’s information guerrillas, ‘to help us save ourselves.’

Its truth is not to be measured by objectivity but by effectivity.

What is true is what can be made to work, which is, in essence, how the laws of physics establish their truth p especially quantum physics: no one knows how its formulae work, they know simply that they do.

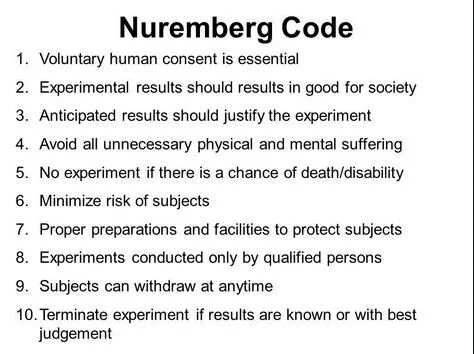

Sometimes this effectiveness is directly instrumental and results in frequent warnings to African Americans to be very wary of the white medial system. These vary from the advice of Dr. Barbara Justice. . . to M’banna Kantako’s warning. . .to Dr. Jack Felder’s call, that African Americans will be safe only when they have developed their own health system. If some whites, with their widespread belief in the benevolence of medicine, are tempted to dismiss this Black mistrust as paranoia, they should listen to Dr. John Heller, the Director of Venereal Diseases at the Public Health Service from 1943 to 1948. Of the men in the Tuskegee study, he said, ‘The men’s status did not warrant ethical debate. They were subjects, not patients: clinical material, not sick people’.

Similarly, African Americans know that they must guard themselves against the white knowledge and the white history presented as truth in the education system. M’banna Kantako educates his children at home. Dr. Leonard Jeffries was demoted for refusing to conform to white educational norms in New York’ City College, and Dr. Jack Felder claims simply that, ‘if we are to survive as a race, we cannot let whites educate our children and we cannot let whites be in charge of our health”.

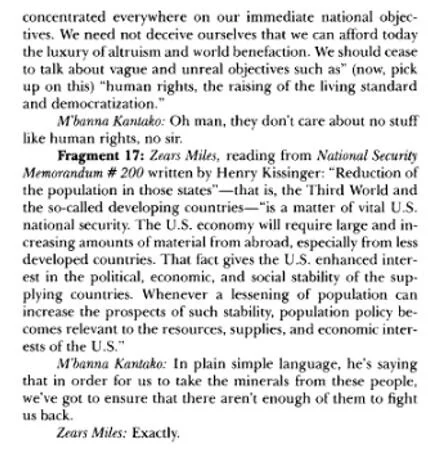

Black knowledge of white genocidal strategy does not involve only the details of its application but also encompasses its motivation. For instance, Black Liberation Radio reminds its listeners frequently that whites are the global minority, only 7% of its population, yet they control the majority of its wealth and its resources. One U.S. Government document frequently referred to in this context is Global 2000, a report prepared by the Carter administration on the world’s population, resources, and environment. Let M’banna Kantako summarize what it means to him:

M’banna Kantako: Brothers and sisters, in Global 2000 what the devil said is, look, for us to continue to get the resources of the earth the way we get them - no charge, we take them - we need to make sure there aren’t enough people to pose any opposition by the year 2000. Now, they were saying that by the 2000, there would be something like 6.3 billion people on earth, and what they said was, in order for us to stay in control, we might need to kill 2.4 billion of them. But this is something more that we need to add to this whole thing here: now they’re saying that there might be 10.2 billion people on earth by the year 2000, and if they stick with the percentage, you know, they’re talking abut wiping off almost 5 billion people.

Global 2000 has become a cardinal document in this Black knowledge of genocide. Its argument for population control, so that the population of the world can be kept in balance with its resources, is decoded unequivocally as a policy for ‘controlling’ or, as Kantako would put it, ‘wiping out’ the people of the ‘Third World’ so that its resources can continue to maintain the white world.

Other stolen fragments of knowledge are brought back into Black territory to support this truth.

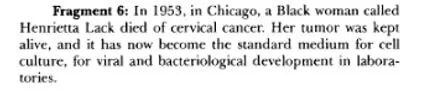

The effective history, constituted by the interplay of these fragments, has characteristics that clearly differentiate it from official history and that official history might use to discredit it. Its motivation is not objective but explicitly political. It knows that the truth that it seeks is not merely lying overlooked and unnoticed by official history, but rather that the truth has been deliberately hidden, and that hiding it is another application of the racial power that would cultivate the AIDS virus in a Black woman’s body (Henrietta Lacks).

The effectiveness of a genocidal strategy depends directly upon the success of it remaining hidden.

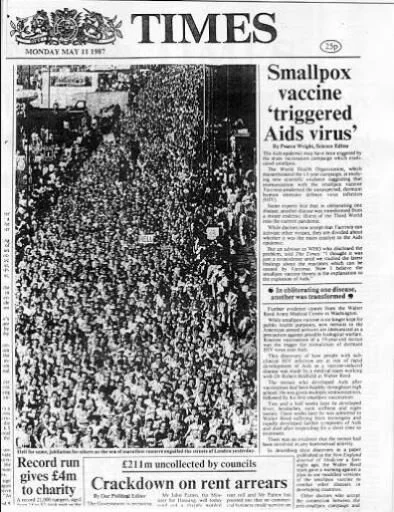

The stolen fragments, forming the material of this history, effectively render the hidden visible. There is no need to understand them in terms of their explicit contextual relations - the rest of the documents from which they are extracted are discarded as value-less. In fact, in general, the document as a whole is not interpreted and not included in the counterhistory. Occasionally, when the discards are ‘included’ in the counterhistory, they are typically treated as ‘evidence’ of a white cover-up. The London Times report detailing the coincidence of AIDS and the WHO’s vaccination campaign in Africa pointedly includes the statement that ‘no blame can be attached to the WHO.’ When Zears Miles reads this out over the radio, Kantako’s laughter is both delighted and skeptical. The lack of direct evidence of the WHO’s intention to spread AIDS may indicate either that the intention did not exist or that it has been successfully hidden.

Interpretation depends upon the construction of relationships. Events, objects, statements do not carry their own meaning but are made to mean by the relations in which they are involved. . . . The one side of articulation is a process of flexible linking while the other is that of speaking or of disseminating the meaning that is produced by the linkage. The fact that white civilian hospitals use Black bodies for research may be linked to medical science, in which case, the Blackness of the bodies does not mean anything; or, on the other hand, it may be linked to the Chemical and Biological Warfare Department’s search for an ‘ethnic weapon,’ in which case, it means everything. . . .

Facts never exist independently or in isolation but rather in articulation with others. Their very facticity is a function and product of their discursive relations. Reusing them, therefore, involves disarticulating them from one set of relations and rearticulating them into another. They are never simply inert, like pebbles on a beach, waiting to be picked up by whoever finds them first. While no fact has any essential existence or meaning of its own, it always has the potential for dis- and rearticulation. Evaluating a fact’s significance, which always involves assessing both how much it matters and what it means, is, thus, a matter of evaluating its potential articulations, their social location and pattern of interests, and their predicted or interpreted effectivity. The constitution of a historical fact is an articulation. Stealing facts, therefore, involves disarticulation.

Writing a history through and of stolen fragments may also be understood by de Cereau’s metaphor of poaching as described in The Practice of Everyday Life. The terrain of knowledge is owned and controlled by the enemy; the poacher darts in and out, taking what he or she needs, extracting it not only from the physical terrain of the landowner, but also from his social relations - ownership, legality, exclusivity. The researcher as poacher has to avoid being caught by the articulation or ways of knowing of the owner; he or she has to guard against being captured by the discursive and social relations within which the quarry is already held.

Producing an effective history, then, is necessarily a practice of social antagonism; it is a counterpractice.

For an example of current effective history, read THE COVID 19 CHRONOLOGY THEY AREN'T SHOWING YOU: PROPAGANDA AND DENIAL ABOUT THE SOURCE OF THE PANDEMIC or watch the video below.