“The Christians from Europe erased our memory. After the terror and trauma of being kidnapped and captured, put in chains, brutalized and raped, put in the bottom of slave ships, the European Christians forbid our ancestors from using our names, speaking our languages, and practicing our culture. Within two generations we forgot where we came from and how we lived. Scared of insurrection following Nat Turner’s revolt in 1831, they decided to indoctrinate us with Christianity to make us docile and obey our slave-masters in return for future promise of a better life after death in heaven. Today, descendants of Binham B’rassa (Balanta people) brought to America, have no memory, no image in our brains, of the quality of life that we lived in Nhacra, our homeland. For six generations we were taught that we had no history and that WE were the savages when in fact it was the Europeans, plagued by a harsh climate, plagues, constant warfare with each other, enslaving each other and their Muslim enemies . . . it was the Europeans who were the barbarians and savages while we had been living a successful, indigenous form of communism for thousands of years. We had wealth in people and cattle, we were great farmers and dominated the local financial markets. We had no rulers or government authority, we paid no taxes and we were free and happy. You have to study these people, these Europeans. You have to really know them to understand how tragic it is that we were enslaved by such a pitiful people with an evil religion.”

- Siphiwe Baleka

English peasant of the 14th Century

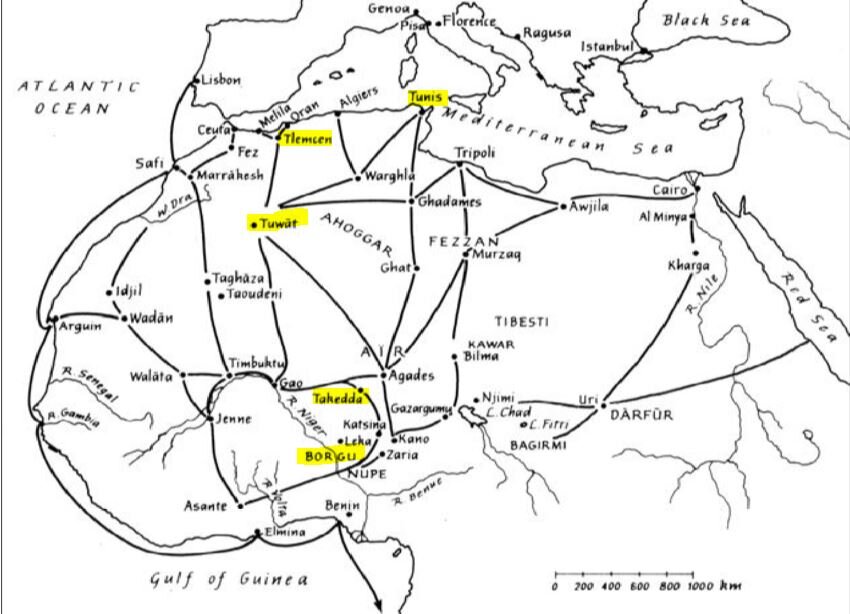

Volume 1 of Balanta B’urassa, My Sons: Those Who Resist Remain documents the Nile valley origins of Binham B’rassa (Balanta people) which occupied the same environment and had a similar lifestyle as other Nilo-Saharan people of the Sudan. From 3,500 BC to 1400 AD, a period of nearly 5,000 years, ancient B’rass (Balanta people) migrated through the Sahel corridor and thus were a part of all the great African civilizations from which they migrated to finally reach the extreme west coast of Africa in the land they called Nhacra in modern day Guinea Bissau. To understand the ancient lifestyle of the Binaham B’rassa, one can start by observing the cultures of that region and understanding the sophisticated cultures of Africa in general..

According to Gomes Eannes de Azurara’s eyewitness account of the Portuguese’s first arrival in the land of Guinea in 1444:

Now these caravels having passed by the land of Sahara, as hath been said, came in sight of the two palm trees that Dinis Diaz had met with before, by which they understood that they were at the beginning of the land of the Negroes. And at this sight they were glad indeed, and would have landed at once, but they found the sea so rough upon that coast that by no manner of means could they accomplish their purpose. And some of those who were present said afterwards that it was clear from the smell that came off the land how good must be the fruits of that country, for it was so delicious that from the point they reached, though they were on the sea, it seemed to them that they stood in some gracious fruit garden ordained for the sole end of their delight. . . . Now the people of this green land are wholly black, and hence this is called the Land of the Negroes, or Land of Guinea. Wherefore also the men and women thereof are called ‘Guineas,’ as if one were to say ‘Black Men.’ . . .”

BALANTA PEOPLE ENCOUNTERED WHITE PEOPLE BEFORE THE PORTUGUESE ARRIVAL IN GUINEA

IBN BATTUTA DESCRIBES MALI IN 1352

When Ibn Battuta first visited Cairo in 1326, he undoubtedly heard about the visit of Mansa Musa (King of Mali from 1307 to 1332). Mansa Musa had passed through the city two years earlier making his pilgrimage to Mecca with thousands of slaves and soldiers, wives and officials. One hundred camels each carried one hundred pounds of gold. Mansa Musa performed many acts of charity and '“flooded Cairo with his kindness." So much gold spent in the markets of Cairo actually upset the gold market well into the next century. Mali's gold was important all over the world. In the later Medieval period, West Africa may have been producing almost two-thirds of the world's supply of gold! Mali also supplied other trade items - ivory, ostrich feathers, kola nuts, hides, and slaves. No wonder there was talk about the Kingdom of Mali and its riches! And no wonder Ibn Battuta, still restless after his trip to Al-Andalus, set his mind on visiting the sub-Saharan kingdom. Here is an excerpt from his travel journal:

“Sometimes the sultan [of Mali] holds meetings in the place where he has his audiences. . . . Most often he is dressed in a red velvet tunic, made of either European cloth called mothanfas or deep pile cloth. . . . Among the good qualities of this people, we must cite the following:

The small number of acts of injustice that take place there, for of all people, the Negroes abhor it [injustice] the most.

The general and complete security that is enjoyed in the country. The traveler, just as the sedentary man, has nothing to fear of brigands, thieves, or plunderers.

The blacks do not confiscate the goods of white men who die in their country, even when these men possess immense treasures. On the contrary, the blacks deposit the goods with a man respected among the whites, until the individuals to whom the goods rightfully belong present themselves and take possession of them.

The Negroes say their prayers correctly; they say them assiduously in the meetings of the faithful and strike their children if they fail these obligations. On Friday, whoever does not arrive at the mosque early finds no place to pray because the temple becomes so crowded. The blacks have a habit of sending their slaves to the mosque to spread out the mats they use during prayers in the places to which each slave has a right, to wait for their master’s arrival.

The Negroes wear handsome white clothes every Friday. . . .

They are very zealous in their attempt to learn the holy Quran by heart. In the event that their children are negligent in this respect, fetters are place on the children’s feet and are left until the children can recite the Quran from memory. On a holiday I went to see the judge, and seeing his children in chains, I asked him ‘Aren’t you going to let them go?’ He answered, ‘I won’t let them go until they know the Quran by heart.’ Another day I passed a young Negro with a handsome face who was wearing superb and carrying a heavy chain around his feet. I asked the person who was with me, ‘What did that boy do? Did he murder someone?’ The young Negro heard my question and began to laugh. My colleague told me, ‘He has been chained up only to force him to commit the Quran to memory.’

Some of the blameworthy actions of these people are:

The female servants and slaves, as well as little girls, appear before men completely naked. . . .

All the women who come into the sovereign’s house are nude and wear no veils over their faces; the sultan’s daughter also go naked. . . .

The copper mine is situated outside Takedda. Slaves of both sexes dig into the soil and take the ore to the city to smelt it in the houses. As soon as the red copper has been obtained, it is made into bars one and one-half handspans long - some thin, some thick. Four hundred of the thick bars equal a ducat of gold; six or seven hundred of the thin bars are also worth a ducat of gold. These bars serve as a means of exchange in place of coin. With the thin bars, meat and firewood are bought; with the thick bars, male and female slaves, millet, butter, and wheat can be bought.

The copper of Takedda, is exported to the city Couber [Gobir], situated in the land of the pagan Negroes. Copper is also exported to Zaghai [Dyakha-western Masina] and to the land of Bernon [Bornu], which is forty days distant from Takedda and is inhabited by Muslims. Idris, king of the Muslims, never shows himself before the people and never speaks to them unless he is behind a curtain. Beautiful slaves, eunuchs, and cloth dyed with saffron are brought from Bernon [Bornu] to many different countries. . . .”

Here, then, Ibn Battuta is describing a Muslim Mali society completely abhorrent to our Balanta ancestors living in the region. Such a society violated their Great Belief which centered on equality. Thus, any kind of hierarchy creating masters and slaves, rulers [kings or Mansas] and subjects, was a direct threat to the Balanta way of life. The idea of shackling children to force them into the foreign indoctrination of a false religion of conquest is an offense of the greatest magnitude.

Here we also learn of the presence of white people and European goods in the Kingdom of Mali during the time when Mali was oppressing Binham B’rassa (Balanta people) who resisted Mali imperialism and engaged in cattle raids against them. Further Antonius Malfante, writing in 1447, describes life in in the Tawat and the Western Sudan Trade:

“After we had come from the sea, that is from Hono [Honein], we journeyed on horseback, always southwards, for about twelve days. For seven days we encountered no dwelling - nothing but sandy plains; we proceeded as though at sea, guided by the sun during the day, at night by the stars. At the end of the seventh day, we arrived at a ksour [Tabelbert], where dwelt very poor people who supported themselves on water and a little sandy ground. They sow little, living upon the numerous date palms. At this ksour [oasis] we had come into Tueto [Tawat, a group of oases]. In this place there are eighteen quarters, enclosed within one wall, and ruled by an oligarchy. Each ruler of a quarter protects his followers, whether they be in the right or no. The quarters closely adjoin each other and are jealous of their privileges. Everyone arriving here places himself under the protection of one of these rulers, who will protect him to the death: thus merchants enjoy very great security, much greater, in my opinion, than in kingdoms such as Thernmicenno [Tlemcen] and Thunisie [Tunis].

Though I am a Christian, no one ever addressed an insulting word to me. They said they had never seen a Christian before. It is true that on my first arrival they were scornful of me, because they all wished to see me, saying with wonder “This Christian has a countenance like ours’ - for they believed that Christians had disguised faces. . . .

There are many Jews, who lead a good life here, for they are under the protection of the several rulers, each of whom defends his own clients. Thus they enjoy very secure social standing. Trade is in their hands, and many of them are to be trusted with the greatest confidence.

This locality is a mart of the country of the Moors, to which merchants come to sell their goods: gold is carried hither, and bought by those who come up from the coast. This place is De Amamento [Tamentiti], and there are many rich men here. The generality, however, are very poor, for they do not sow, nor do they harvest anything, save the dates upon which they subsist. They eat no meat but that of castrated camels, which are scarce and very dear. . . .

It never rains her: if it did, the houses, being built of salt in the place of reeds, would be destroyed. It is scarcely ever cold here: in summer the heat is extreme, wherefore they are almost all blacks. The children of both sexes go naked up to the age of fifteen. These people observe the religion and law of Muhammad. In the vicinity there are 150 to 200 ksour [oasis].

In the lands of the blacks, as well as here, dwell the Philistines [the Tuareg], who live like the Arabs, in tents. They are without number, and hold sway over the land of Gazola from the borders of Egypt to the shores of the Ocean, as far as Massa and Safi, and over all the neighboring towns of the blacks. . . . They are governed by kings, whose heirs are the sons of their sisters . . . . Great warriors, these people are continually at war amongst themselves. The states which are under their rule border upon the land of the Blacks. I shall speak of those known to men here, and which have inhabitants of the faith of Muhammad. In all, the great majority are Blacks, but there are a small number of whites [i.e. tawny Moors].

First, Tbegida (Takedda, five days’ march west-south-west of Agadez), which comprises one province and three ksour; Checoli (Tadmekka, north of Takedda) which is as large. Chuciam (Gao), Thambet (Timbuktu), Geni (Djenne), and Meli (Mali), said to have nine towns. . . .all these are great cities, capitals of extensive lands and towns under their rule. These adhere to the law of Muhammad.

To the south of these are innumerable great cities and territories, the inhabitants of which are all blacks and idolators, continually at war with each other in defense of their law and faith of their idols. Some worship the sun, others the moon, the seven planets, fire, or water; others a mirror which reflects their faces, which they take to be the images of gods; others groves of trees, the seats of a spirit to whom they make sacrifice [Siphiwe note: here is reference to Balanta spirituality]; others, again, statues of wood and stone, with which, they say they commune by incantations. They relate here extraordinary things of this people.

The lord in whose protection I am, here, who is the greatest in this land, having a fortune of more than 100,000 doubles [a billion coin], brother of the most important merchant in Thambet (Timbuktu), and a man worthy of credence, relates that he lived for thirty years in that town, and, as he says, for fourteen years in the land of the Blacks. Every day he tell me wonderful things of these peoples. He says that these lands and peoples extend endlessly to the south: they all go naked, save for a small loincloth to cover their privates. They have an abundance of flesh, milk, and rice, but no corn or barley. . . . These people have trees which produce edible butter, of which there is an abundance here. . . .The slaves which the blacks take in their internecine wars are sold at a very low price . . . .Neither there nor here are there ever epidemics. . . .They are great magicians, evoking by incense diabolical spirits, with who, they say, they perform marvels. . . .Of such were the stories which I heard daily in plenty. . . . The Egyptian merchants come to trade in the land of the Black with half a million head of cattle and camels - a figure which is not fantastic in this region. The place where I am is good for trade, as the Egyptians and other merchants come hither from the land of the Blacks bringing gold, which they exchanged for copper and other goods. Thus, everything sells well; until there is nothing left for sale. The people here will neither sell nor buy unless at a profit of one hundred per cent. . . . Indian merchants come hither, and converse through interpreters. These Indians are Christians, adorers of the cross. . . . “

It should be noted now that from the 10th century to the 15th century, Binham B’rassa people did not live in some backwards “primitive” culture. They lived on the margins of one of the greatest centers of world trade where there were people from all over the world. Binham B’rassa lived on the margins of this society, intentionally rejecting and resisting it because of the cost to their freedom, way of life, spirituality, and dignity. They wanted no part in this international trade organized by oligarchies that exploited and enslaved people. Finally, a study of European history shows that the “internecine” warfare was no more characteristic of the African people of the region than it was of the European peoples who were constantly engaged in internecine warfare and struggle of power, pauperizing, enslaving, and killing their own people throughout the European continent.

By the time Binham B’rassa (Balanta people) settled in Nhacra on the Atlantic coast, Walter Rodney writes in A History of The Upper Guinea Coast 1545 to 1800,

“It is only the Balantas who can be cited as lacking the institution of kingship. At any rate there seemed to have been little or no differentiation within Balanta society on the basis of who held property, authority and coercive power. Some sources affirmed that the Balantas had no kings, while an early sixteenth-century statement that the Balanta ‘kings’ were no different from their subjects must be taken as referring simply to the heads of the village and family settlements. . . .as in the case of the Balantas, the family is the sole effective social and political unit. . . .”

The distribution of goods, to take a very important facet of social activity, was extremely well organized on an inter-tribal basis in the Geba-Casamance area, and one of the groups primarily concerned in this were the Balantas, who are often cited as the most typical example of the inhibited Primitives. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Portuguese realized that the Balantas were the chief agriculturalists and the suppliers of food to the neighboring peoples. The Beafadas and Papels were heavily dependent on Balanta produce, and in return, owing to the Balanta refusal to trade with the Europeans, goods of European origin reached them via the Beafadas and the Papels. The Balantas did not allow foreigners in their midst, but they were always present in the numerous markets held in the territory of theirs neighbors.”

In Planting Rice and Harvesting Slaves: Transformations along the Guinea-Bissau Coast, 1400-1900, Walter Hawthorne writes,

“In the early sixteenth century, the Rio Cacheu was situated on the frontier of the Casa Mansa (or Casamance) kingdom and possessed a mixed population of Cassanga, Mandinka, Floup, Balanta, Brame and Banyun. Some of these groups were incorporated into Cas Mansa. Others operated as politically independent communities. The groups attached to Casa Mansa recognized the rule of the Cassanga king, who in turn paid tribute to the Mandinka kingdom of Kaabu. Casa Mansa prospered by controlling trade between the Rio Cacheu and Rio Gambia and the interior and by manufacturing and marketing cloth. Cassanga fairs attracted as many as 8,000 people, including ‘Portuguese,’ who traded iron, horses, beads, paper and wine.”

It is evident, therefore, that Binham B’rassa lived in a delicious, green land of fruits. By virtue of their cattle and superior agriculture, Balanta dominated a thriving and organized local economy connected to a larger, global economy, and had a secure position in it.

To get an understanding of the quality of life on the coast of West Africa, one need only watch these scenes from the movie Roots. The scene takes place in Gambia, just north of the Binham B’rassa homelands and depicts life of the Mandinka.

Life in Guinea Bissua

Now we have an image of the reality of life on the coast of Guinea before the arrival of the soldiers, mercenaries and representatives of the Chivalric Order of Jesus Christ from Portugal. They were then followed by the Christians of England. Below is what life was like in the land of the English Christians before they came to Guinea and the savage history of the Christians in Europe. Remember, Europeans were both slaves and slave traders of their own European people from the 8th to the 11th century!