The following notes are taken from the book, The Origins of African-American Interests in International Law by Henry J. Richardson III. Among other things, Professor Richardson is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a past vice president and honorary vice president of the American Society of International Law, and a founding member of both the National Conference of Black Lawyers and the Project on the Advancement of African-Americans in International Law. The Notes are a continuation of a series of articles on Legal Issues Affecting the Balanta people:

ON QUESTIONS OF RACE, ETHNICITY AND NATIONALITY

SUMMARY OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE

ORIGIN OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE IN THE UNITED STATES

DEVELOPMENT OF LEGAL ISSUES DURING THE BALANTA MIGRATION PERIOD

LEGAL ISSUES EFFECTING BALANTA AS A RESULT OF CONTACT WITH EUROPEAN CHRISTIANS

LEGAL ISSUES EFFECTING BALANTA AS A RESULT OF CONTACT WITH THE ENGLISH

Timeline of American History And The Birth of White Supremacy and White Privilege in America

DEVELOPMENT OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE

NOTES

“This book is accordingly about African-Americans and the beginnings of their acting as participants, in Myers McDougal’s term, in the international law process. They could not ‘participate’ in the 16th through 19th centuries as did the sovereign governments and their leaders and high officials of empires in the Londons, Paris(es), Lisbons, and Madrids of the world, or even as the local governments of colonial territories in the New World did, for example, in the thirteen colonies of British North America. But collectively African slaves and African-heritage people were the target and focus of much international concern among those same governments, and periodically they acted to leverage or protect themselves against those governments. African-heritage peoples were impacted by the stream of decisions, interpretations, and jurisprudential formulations about international law during those centuries. . . . There is no doubt that wherever they were in the New World. . . African-heritage people ‘participated’ in the international legal process, even if they lacked formal standing under that law to do so. Discrepancies among three areas: the perceived realities of international concern about African slaves in the New World, their impact on European’s lives and objectives, and the absence in the applicable European-prescribed international law of principles and procedures granting African slaves/African-heritage people access to legal decision making under the law, raise at least two categories of inquiry. One is about the adequacy of that legal system(s) to do justice to all the people it governs or affects. The second is about the story of the normative relationship and the demands of the excluded people(s) to that legal system. Specifically, it concerns what that law ought to hold regarding slaves, as it in practice operated to govern or take their lives while barring any short-run chance for them to influence its commands or enforcement. There was some promise for African-heritage people in international legal doctrine, at least in theory . . . . However, the promise faded as the jurisprudential underpinning of international law shifted from natural law to territorial sovereignty.” p xxix -xxx

“Since African-heritage people during this period were barred from being formally trained as, nor had access to international (or any other kind of) lawyers (save extremely rare exceptions), we must find their demands in the various forms that they were actually expressed, e.g., with their feet, as well as with their mouths or pens. We can then interpret the content of these demands as pleas for relief under ‘better’ international law that Black people would have demanded to exist, had they had access to the legal process with the requisite opportunities, education, resources, and advocacy skills to be effective within the rules, rituals, and decisions of that process. . . . Black folks made what we call an implicit claim when there were no overt words or direct expression demanding better international law but when by their actions they indicated by implication, in context, a demand for more freedom. As the content of their demand is familiar to international law (even though it was not agreeable to contemporary authoritative doctrine), we can call this interpreted demand an implicit claim; furthermore, it reflects an interest that African-heritage people had in interpreting, prescribing and implementing international law.” p. xxx

“. . . .the Africa-American International Tradition, which pre-dates the founding of America as a nation. This Tradition generally refers to the history of Blacks invoking the linkages between their freedom and international issues. . . . And so this book explores the birth of this Afro-American International Tradition and particularly the roots of African American’s stake in international law. . . . The historical period also roughly corresponds to two other key historical creations of humankind grouped around the Atlantic Ocean basin: the rise of international law as a modern legal system, particularly among European states and their Atlantic colonies, and the rise and flourishing of the international slave trade in African(s) by European merchants and governments into the New World.

Only by placing African slavery in the British North American colonies in the context of the International Slave System encompassing and linking the New World, can the actions, struggles, demands, and decisions of slaves and Free Blacks in North America relative to international law be properly understood.” p. xiii -xv

“Thus the central notion of Black people making claims/demands to be governed by a better outside law and to define and protect rights to freedom and equity that they are denied by their white governance under local law, stands in this regard on familiar jurisprudential ground. . . . These people were generally claiming against community authority and not to it.” p. xxi

“Blacks, when they made claims for a better outside law, including a better international law, to govern them, were definitely claiming for a new or radically reformed constitutive process of authoritative decision for both the United States, from the 17th into the 19th centuries, and for the contemporaneous international community. They largely had to construct their own opportunities to make such claims and usually did so at great personal and political risk. . . . Black claims were largely made in resistance to the constitutive process of slavery. The results Black were demanding required the actual replacement of slavery with racial equity. . . . White officials, populations, and elites were determined not to permit these same rights to come into contemporary legal, moral, cultural, economic, religious, or political existence. . . .By contrast . . . Blacks . . . had rights to be free of slavery and racism, to live in human dignity on some normative basis that lay outside of existing constitutive process, and that their validity was not touched by the ubiquitous opposition of the surrounding slavery - supportive local and national process. . . . they were claiming to outside law as an identified normative system, in their eyes, outside of the local rules and norms of their enslaved captivity. . . . Blacks identified and invoked, in particularly situations, one or more such bodies of norms through their belief and interpretation that those outside norms gave them a right to freedom, and therefore comprised better law by which they should be governed. Outside law was defined by Blacks’ interpreted beliefs about other outside criteria of right and wrong . . . . . ” p. xxii -xxiii

“That the then-existing international legal decision makers and officials had no concern for the substance of Blacks’ claims, or for granting Blacks’ access to make them, does not control the present discussion, because it does not touch the integrity of the connection between such claims being made and the emerging African-American experience. Knowingly or not, Blacks were making demands to re-interpret and normatively change international law, which after all evolved, at least in part, to protect the burgeoning International Slave System in the New World, and whose principles from the beginning had to cope with its existence. Blacks were not, for the most part, claiming that their behavior in rebelling, opposing, and contradicting their enslavement and the racism directed against them was legal under contemporaneous international law. And they knew that such behavior was illegal under slave codes and other similar local law, beginning in the late 17th century.” p. xvii

“As [the American] Revolution approached, the contradiction between white European colonists’ publicly applying metaphors of ‘slavery’ to describe their relationship with the Britain of King George III, and the actual circumstances in which they were profiting from ‘their own’ African slaves under their noses and in their own houses, stimulated new kinds of Black claims to natural law. These included, implicitly, claims to international law to the extent that it was then still based on natural law, as Grotius had formulated. . . . the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1776 . . . put Blacks squarely in the middle of two contending candidates for sovereignty over the same territory of North America’s eastern seaboard, and therefore they were naked - as a group - on the international stage. They had to choose their loyalties or at least their most likely survival options, but, in fact, as a group they chose their most likely freedom options. In numbers most Blacks saw the British as potential liberators and chose to try to help their fight or at least seek security by moving towards their military lines and encampments. Caught up in the approaching military battles, their decisions often had to be made quickly about, literally, which way to run.“ p. xviii

“When the Revolution successfully defeated the British, the British honored their obligations under international law by taking at least 30,000 ex-slaves with them back to Britain. Analogously, the Colonists honored theirs by manumitting up to 12,000 slaves who had fought for them, while bitterly opposing the British removing any of ‘their’ slaves at all. Post-Revolution questions turned to the need of the new nation and its fractious thirteen sovereign states for new constitutive arrangements under which to govern itself. The issue was not whether, but how international law was to be incorporated in such new arrangements and documents. As a dozen or so years passed of mounting troubles which threatened the Union, how would this issue unfold in 1787 in the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia? Blacks were frozen out of that august body of Founding Fathers, but were entering a new stage of social and political organization, especially in Pennsylvania and other parts of the North. They already possessed a history of claims to outside law, including international law, arising out of their life in America. And they necessarily had interests in the outcomes of the Constitutional debates about the international law-related provisions of the Constitution, even if the legal historian must provide heuristic assistance to give such interests concrete form after all these years. . . . What interests in the outcomes of the Framer’s debates about drafting the international law-related provisions of the Constitution did Blacks have? . . . Further . . . .the consequences of the British abolition of the international slave trade among its colonies in 1799, and of American governmental actions to conquer Florida territory and destroy that sanctuary from American slavery for Black slaves and Black Indians vis-a-vis Spanish ownership. . . .” p. xix-xx.

Early Historical Trends

“During the period roughly from the 15th to the middle of the 19th centuries, a group of Western European sovereign states, driven by strong imperatives of exploration for new trade routes to the Far East and new sources of wealth, discovered and helped create profitable markets for black African slaves. Their justification in part, but by no means exclusively, for conducting this increasingly lucrative trade in black human bodies came to refer to a variety of Christian doctrinal rationales, such as the benefits to the slave of rescuing him from his own primitivism and giving him the opportunity to serve Christian society. . . . The 19th century historian W.O. Blake noted that

‘….It is upon (Africa) in an especial manner that the curse of slavery has fallen. At first it bore but a share of the burden; Britons and Scythians were the fellow slaves of the (African): but at last all the other nations of the earth seemed to conspire against the negro race, agreeing never to enslave each other, but to make the blacks the slaves of all alike… and the abolition of the practice of promiscuous slavery in the modern world, was purchased by the introduction of slavery confined entirely to negroes . . . .’

Thomas notes that in 1250, slavery was covered in some detail in the Spanish legal code. The latter specified that a man became a slave by being captured in war, by being the child of a slave, or by letting himself be sold. . . . It is noted here in passing that this early, codified partial connection to prisoner of war status in legally defining a slave presaged several future issues in various legal systems about the connection between, and even the definition of, ‘war’ and the freedom status of individuals or groups in particular contexts.

Thus generally from the 11th through the 14th century in Europe, slaves used for personal service, in urban crafts and workshops, and on farms were held and traded in and around the Mediterranean Sea. They included a wide diversity of ethnic origins, both white and black. African slaves - Muslim and otherwise - were certainly present in Spain and Italy, and became more numerous towards the 15th century. Thomas estimates that in the late 15th century the Venetians had as many as 3000 slaves.

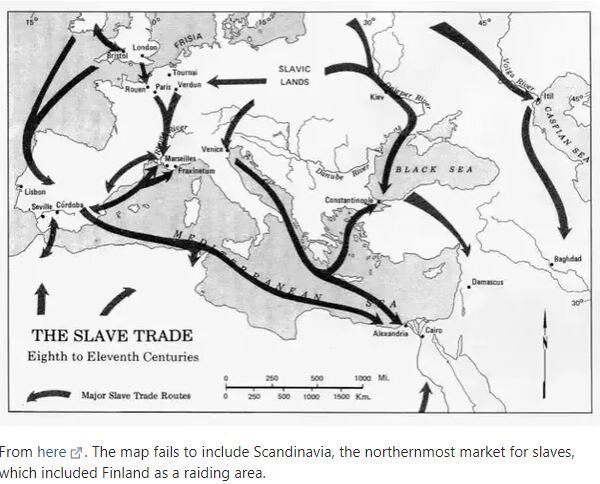

The slave trade for Africans flourished even more on the southern shores of the Mediterranean than the northern, a condition going back to the late Middle Ages. This traffic can be connected to the trans-Saharan slave trade that stretched across the Saharan into the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Eastern points beyond. As we shall see, it drew in African slaves from the West African interior. That trade would . . . begin to link up to and interact with a second slave trading process begun by the Portuguese exploration of the West African coast beginning in the mid-13th century, through their forays for gold, goods, and slaves as they explored deeper inland from that coast.

Maritime raids on Spanish and Italian villages and shipping by Muslim raiders produced Christian captives, and there was a long-established traffic in black African girls and young men, beginning in the late Middle Ages. The Malian empire in West Africa, and then its successor Songhai Empire helped replenish the supply through trade and capture from upper Niger, for example, slave girls from Awdaghost. These slaves appear to have been obtained to be servants, concubines or warriors. The emperors of Songhai would customarily make presents of slaves, sometimes as many as 100 at a time, to their guests. Also, beginning in the Middle Ages, African slaves were traded to Java, India, and China.

There was therefore a trans-Saharan slave trade which may have begun as early as 1000 B.C. and which was active following the late Middle Ages, as well as slaves beginning to be traded by Arab traders out of East African ports during the latter period. During the period approaching the 15th century, somewhere between 5,000 and 20,000 slaves may have been annually carried north from the Niger region to the harems, barracks, kitchens, or farms of the Muslim Mediterranean and the Near East during this period, as well as into Christian southern Europe.” pp 4-5

The Opening of the West African Slave Trade

“In the 13th century, Europeans, especially the Italians beginning around 1290, set out to explore the West African coast in an attempt to reach India. A first expedition was lost, but it represented the beginning of a drive to explore, by Portuguese, Spaniards, Genoese, and Florentines of first, the outlying islands, and then the West African coat. These explorers were acting on information and rumors of gold through, inter alia, Jewish merchants in Majorca who had established patterns of trade in North African ports, even in Saharan oases, and as far south as among the Fulani people in Senegambia. This information was put to good used by the cartographers of Majorca. In the 14th century Canary Islanders were occasionally imported as slaves in both Portuguese and Andalusian ports, as well as into Seville in 1402.

By this time there was some exploratory and commercial interest in seeking black African slaves as well as gold from West Africa. Prince Henry the Navigator, of Lisbon, embodied this interest. He decided that West African gold and slaves, specially as they could be found on the coast of Guinea, might be reached by sea rather than through trans-Saharan trade routes. He sponsored a series of expeditions which first seized the deserted islands of Madeira and Azores, perhaps to keep them, imperialistically, out of the hands of the Spaniards. A series of further expeditions moved slowly south down the West African coast. At Cabo Branco, in the extreme north of the present state of Mauritania, the Portuguese found a market run by Muslim traders and a rest station for trans-Saharan caravans. Here they received a small quantity of gold dust, and seized 12 Black Africans to take back to Portugal as ‘exhibits’ to show Prince Henry. Black slaves were already known in Portugal since at least 1425. Other Portuguese expeditions to West Africa followed, some of which returned with small numbers of Black African slaves. In 1444, a company for trade to Africa was formed ans a royal monopoly. And from this time forward, kidnappings of more and more Africans occurred by Portuguese captains in ever more southerly latitudes.

As Thomas notes, the early history of the Western exploration of the African coast went hand-in-hand with the rise of a new Atlantic slave trade. African kidnappings became increasingly brutal as Africans learned to defend themselves. And this trade also helped finance scientific discovery, which was one objective of Portuguese exploration. The Portuguese soon began to buy rather than kidnap slaves, often through Muslim merchants, as captives of war or raiding parties. By 1448, about one thousand slaves had been carried back by sea to Portugal or the Portuguese islands of the Azores and Madeira. Thomas’ characterization of West Africans’ reaction to the increasing taking of slaves is noteworthy:

‘The attitude of the Africans to transactions of this kind with the Europeans can only be guessed. The sale by any ruler of a person of his own people would have been looked on as a severe punishment; when African kings or others sold prisoners of war, they looked upon the persons concerned as aliens, about whose destiny they did not care, and whom they might hate. For there was no sense of kinship between different African peoples. Such prisoners, however obtained, were the lowest people in society, and, even in Africa, would have been used to do heavy work, including in gold mines.’

However, others provably looked upon what they were doing as a regrettable action of necessary policy to either maintain themselves in power or to protect the greater good of their tribe in relation to more powerful neighboring tribes and alliances. . . .

Portuguese trade with West Africa at first was confined to African coastal communities, sometimes described as ‘local despotic kingdoms,’ but they soon penetrated up the Gambia River to establish contact with the powerful Songhai empire. through its rich, sophisticated capital at Gao, with an estimated population of from 10,000 to 30,000, the Songhai controlled most of Western Sudan and the trade between West and North Africa. Slaves were obtained by them, as previously noted, by raids against non-Muslim African peoples to the south, and the Songhai used them on royal farms when not selling them to Arab traders.

The Portuguese traded horses for slaves - at 10 to 15 slaves for one horse - and helped introduce these animals into West Africa, where they would sometimes be used as cavalry units in battle. They also introduced other goods in trade for slaves, including woolen and linen cloth, solver, tapestries, and grain. Thomas notes, further:

‘The establishment by the Portuguese of a small trading post, feitoria, at Arguin, and the export thence of a few thousand slaves, seemed neither significant or outrageous. Always the Portuguese would enter into negotiations with the rulers, either small-scale or grand, and these became as it were allies with the newcomers, jointly concerned to make profits from trade.’

African slaves were soon being bought in Portugal by a range of people of varied economic classes. Moral ecclesiastical approval had been secured from a succession of popes. By 1460, the holding of black slaves had become a mark of distinction for Portuguese households. . . . Thus, the African slave trade to Europe was formally opened, as the significant prelude to the more systematized barbarities against Africans that would soon accompany Portuguese and other European exploration of the New World, following Columbus’ ‘discovery’ of America in 1492.” p. 5-7

The Discovery and Colonization of the New World: The European Need for Servile Labor

“…Columbus had lived on the Portuguese plantation island of Madeira with its substantial population of slaves. In 1482 he probably visited the Portuguese fort and slave factory at Elmina on the West African Coast. In this regard, Thomas notes that Columbus was a product of the ‘new Atlantic slave powered society,’ and he may have, though there is no confirmation of this, carried a few slaves on his voyages to the Caribbean. He has the dubious distinction of having made the first Atlantic slave shipment, from west to east, sent from Santo Domingo to a good friend in Seville, of Taino Indians captured in the Caribbean, who had resisted his capturing them.

This was followed by a subsequent shipment of 400 such captives, whose sale in Seville was annulled on order of the King because of doubts about the legality of the transaction, as was a similar such sale by Columbus himself upon his return in 1496 with thirty Indians to sell as slaves. . . .But in 1502, Queen Isabella, having refused permission to import ‘Indians,’ nevertheless permitted the importation of ‘cannibals’ who might be ‘fairly fought and if captured enslaved as punishment for crimes committed against my subjects’; such ‘crimes’ included resisting the latter’s Christian teachings. . . .

Who was going to do the extremely difficult, continuously essential work of farming for necessary food for European settlers? Of local manufacture for necessary implements unable to be imported from Europe? Of land-clearing, construction, tilling, harvesting and processing of cash crops, and numerous other tasks for daily life, survival, and economic growth in the new settlements? And who would do the hard labor of producing, beyond the above, goods and crops for export such as sugar and tobacco? These were being demanded by the metropolitan sovereigns, markets and private investors with stakes in particular settlements, as well as by local emerging entrepreneurs demanding profit from overseas for themselves and the settlements.

A key part of the story of the slave trade and the bringing of African slaves to the New World, including North America, is the ongoing search for satisfactory-to-European elites answers to this question of labor. . . . But it was equally a continuing consideration, not only for the foreign policies of European sovereigns towards each other, but also for the public norms of morality and legality within European nations themselves, of who could rightly and legally be enslaved in the service of expanding overseas state and investor capitalism. With the establishment of settlements by all major European states throughout the Western Hemisphere, it also became a common dilemma among all governmental and commercial participants in the discovery-empire-settlement-colony-domination of trade international process. Thus these issues were bound up with the emergence of modern international law. . . .

The Indian population on Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico was then in rapid decline from Spanish mistreatment and imported diseases, and it seemed clear to the Spanish colonial authorities, after a wave of island kidnapping, that native Indians in the Caribbean both would not and could not be sufficiently enslaved to work the newly opened gold mines on Hispaniola. Thus in January, 1510, King Ferdinand gave authority for fifty of the ‘best and strongest’ slaves to be sent to Hispaniola to work the mines, and it was clear that Africans already in Europe were intended here. This was followed by a royal decree three weeks later to send another 300 to Santo Domingo for sale to whomever would buy them, with the purchase of a tax permit for a license. The requirement to buy this permit was soon to become an important source of income to the Spanish Crown. Thus, this was the beginning of the slave trade to the Americas, with gold in Hispaniola as the incentive. . . .A few years later, in 1518, there was another shift in Spanish royal policy regarding African slaves being sent to the New World. King Charles had been receiving two lines of advice on these matters. One, put forward by Bishop Las Casas and a few other clerics, was that it was wrong and even un-Christian to continue to attempt to enslave the indigenous Indians in the Americas, given the degree of Spanish cruelty involved and the apparent fact that they were ill-suited to the work. The recommendation was that African slaves should be used instead, since, so it was thought, they were both more physiologically and temperamentally suited to do and survive the hard labor, and doing so would save Indian lives.. Second, African slaves born in Europe once taken to New World Spanish colonies were more likely to revolt and inspire the indigenous Indians into insubordination than were bozales - Africans shipped into slavery directly from Africa and thence to Spanish colonies. The King accepted these recommendations in 1518, began to grant licenses, and thus the African slave trade to the New World was born. These slaves were soon put to work in the harsh sugar mills which were beginning to be built after the relative ease of bringing in sugar crops was discovered, and also in the gold mines in Cuba and elsewhere. But almost immediately Spanish authorities in, e.g., Cuba were faced with opposition and revolts by the bozales, which it tried to counter by prohibiting the importation of Africans from certain, primarily Islamic areas. By 1530, this trade was well established, there were more people of African blood than of Spanish blood in Hispaniola, and the trade would continue for the next 350 years to be a source of profit for the merchants involved, as well as for the Crown. . . .In this connection, the Spanish had as early as 1518 moved to license on an international scale the import trade in African slaves (by means of the asiento) . . . .Under the ultimately unsuccessful Spanish policy, which was a primary strategy in Span’s attempt to dominate the New World slave trade, asientos were auctioned to the highest bidders, generally among Dutch, Portuguese, French, or English traders. . .

The first English voyages to the West African coast began in 1532, and although a few Africans were brought back for display (and later returned home), the main objective of these explorations was the African trade in gold and other commercial goods, but not the slave trade. The Portuguese got sufficiently concerned in 1555 to send a special mission to the British Crown to remind Queen Mary of the papal grants of Portuguese monopoly in Africa and therefore to prevent any further English voyages to Guinea. The Privy Council in London accordingly issued a prohibition, but the understanding with the Portuguese was soon infringed upon by further British voyages.

In 1562, Captain John Hawkins, whose father had made the first exploratory British voyage in 1532, initiated the English slave trade. . . His expedition of three ships wound up ascending the river Sierra Leone where he forcibly captured three hundred or more Africans who had already been assembled for slave shipment by Portuguese traders. . . .This commerce was illegal under Spanish law and was the forerunner for a future, intense pattern of smuggling. His merchandise in the hulks was confiscated in Spain, but he returned to London in September 1563, with a good profit for his investors. A second Hawkins voyage followed . . . A battled ensued, although England and Spain were not at war; . . .

English settlers from London were beginning to make reconnaissance voyages to the New World. They settled in Bermuda in 1609, soon thereafter in Virginia and Massachusetts, and then into the Caribbean: Barbados in 1625, and Antigua, Nevis and Montserrat by 1632. With all of these moves, the great labor problem was a main concern, as it was in Virginia in 1619. The landing of slaves in Virginia signified that the slave trade was inaugurated on the North American mainland before the new European settlers entered the slave market. Even prior to this, however, a British company was formed and chartered by the Crown to control the African trade, and the moving spirit of that venture, Robert Rich, already owned a tobacco plantation in Virginia and was probably hoping to take black slaves to work it, and from 1619 Africans began to be taken into Virginia in small lots. . . . In 1630 King Charles I granted a royal license to a separate company to transport slaves from Guinea and did so through the English fort (slave factory) at Cormantine on the Gold Coast; the next British slave factory would be built in 1661. The success of this company in slave trading drew in other investors and traders. By the late 1630’s, a few African slaves were to be seen in most of the European North American colonies, and slave-trading ships began to be constructed in Massachusetts. . . .

Plantation owners, farmers and other settlers were now turning to African slaves as a cheaper source of labor in the long run, notwithstanding the deadly horrors of the Middle Passage. They were seen also as easily identifiable and controllable

to prevent their escape from labor arrangements

which, by the last decades of the 17th century, were on their way to being made permanent under law in North America. . . In 1661, the Virginia Assembly would extend statutory recognition to slavery over both Indians and Africans, and in 1662, it would make such slavery permanent. The British Parliament would enact similar legislation for its New World colonies in 1667.

A rising ideology of race and European perceptions of Africans as ‘the Other’ facilitated further the permanent enslavement of their heirs and successors. . . . There also seems little doubt that the European-driven ‘necessity’ and increasing profitability of the African slave trade to the New World beginning in the 16th century stimulated supporting normative, doctrinal, religious, legal and public policy concepts in a pattern of European and then Euro-American attempts to morally justify this vastly accelerated system of enslavement. . . At least one scholar has historically attributed the rise of such racial ideology to Christianity’s clash with Islam as it played out in Europe. From the 8th to the 13th century the relatively limited forms of slavery in Europe had generally been in decline. But the clash with Islam eventually encouraged Christians to follow the Muslim lead in barring the enslavement of fellow-believers, while retaining such possibilities for those who, were, or had been, non-believers. This basis for a right to manumission for baptized slaves was deliberately eliminated in Virginia law in the 17th century and then in the other North American colonies as African slavery was made permanent . . .

Thus a solution was considered to have been found to the common problem of labor as one of the most difficult dilemmas in the entire New World economic process, and thus the major pre-occupation of economic gain by imperial governments, merchants and settlers began to be addressed through the use of human beings solely - to the extent this could be arranged - as economic units.

The slave trade was big European and international business in the 17th and 18th centuries, and it was largely in the hands of Dutch, French, and English companies. The Dutch in the 17th century aimed to seize control of the commercial routes to the New World, including the slave trade. Thus, two years after the Twenty were landed in Jamestown from a Dutch man o’war, the Dutch West India Company was formed in 1621 to monopolize those trade routes and to challenge the previous Portuguese slave trade dominance.

However, the Dutch lost their bid for dominance after the late 17th century in wars with France and England. . . . . Concurrently, by the mid-17th century, many individuals and organizations in England, including the powerful East India Company, were involved in the slave trade, and concerned about their future investments in it. The English evolved the objective of trying to drive the Dutch and French out of West Africa. And indeed by defeating the Dutch (with French help) England enhanced its prestige in Africa. Moreover, the French defeat in the War of the Spanish Succession gave England the asiento - the exclusive license to take slaves to the Spanish colonies - for 30 years. In 1672, the Royal African Company was chartered by the King of England and for the next decade held a monopoly on that trade. For the next 50 years it would be the most important single slave trading group in the world. It would lose its monopoly in 1698, give up the slave trade in 1731 . . . .

The European revival of Middle Ages slavery was drawn away by rapidly growing markets for African slaves with their huge profits, together with those from gold, sugar, and the industries supporting the considerable expansion of the international slave trade. In the midst of this European drive, increasingly a British drive, to dominate both the trade of bringing valued goods, delicacies, and New World luxuries to the European market and the international slave trade to the New World, European-based systems of colonial law appeared to facilitate this process. “. pp.8-16

African Resistance and Cooperation

“The question of the extent to which Africans resisted and also cooperated in their own enslavement over three or more centuries is one that reminds us that History is an interpretation of the past written in the present. Present interpretations are affected by present day community expectations about major value questions, not excluding that of race, regarding African-heritage peoples in Western societies and the ongoing, increasingly rancorous debate about what legitimately constitutes racism and invidious discrimination. This includes the issue of what actions and situations of deprivation must be deemed the responsibility of those deprived. Similarly, present canons of historiography are freighted with the question of whether the present historian should judge a s wrongful the events and trends of the past that obviously destroyed much and injured or killed many, or whether he or she should forego such judgment through notions of generational tolerance. The latter generally argue that those actors in that time period had no choice but to obey the perspectives and imperatives of that period and are therefore beyond the moral judgment of a later historical period. And during these present years, the question of slavery and the slave trade has not been exempt from such notions.

Perhaps even more so, slavery and the slave trade have, as subjects of historical interpretation, been subjected to versions of contemporary policy strategies about African-heritage peoples and race that have been strongly promoted by politically conservative forces in the United States and elsewhere beginning , in its current phase, with the Reagan Administration in 1981. The overall aim of these strategies appears to be, inter alia, to decrease the moral turpitude of Euro-Americans and Europeans and their forefathers for their establishing an international slave system. More specifically it seems to be to minimize the ‘wages and badges’ of slavery - in the words of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution - in the present day that have so continuously and clearly afflicted all African-Americans and other African peoples in both the Americas and in Europe down to the present moment. These strategies are numerous; indeed, they constitute whole barrages on a number of levels, and they are conducted both consciously by determined proponents and unconsciously by others more unsuspecting who have absorbed them from the surrounding political and intellectual atmosphere. One outcome, grossly destructive in its effects but really only the top cap of a formidable submerged iceberg, is the strong trend of rights-reversal that has now taken hold in American law directed against African-Americans, which has been well documented.

Other strategies are more subtle because they are intermixed with entirely legitimate intellectual inquiry and rely more on shifts of emphasis for their effect in creating yet another little bit of discriminatory smoke in the atmosphere. One such is the contextualization of African slavery in comparative terms with the harshness of treatment of other groups of deprived people who happen to be white, e.g. claims that African slavery can only be validly assessed in comparison with the actual detailed material plight of European peasants in the 14th century. Building up a plethora of deprived peoples in similar material circumstances tends to dilute any assigned moral responsibility for African slavery and the treatment of African persons thereby, by burying them in common comparative historical misery and thus erasing causal arguments traveling to the present day. These days, of course, somehow much of such ‘new and path-breaking’ scholarship seems to lie in that comparative direction, and comparatively little in the opposite direction, i.e., that on re-examination, African slavery was uniquely horrible and even worse, with wider consequences than previously thought. That such issues divide the Black and white American academy is not surprising. Their treatment is par of the reason that in a number of disciplines, including law, African-American scholars joined by other scholars of color have turned their considerable attention to basic questions of jurisprudence and methodology. They have done so in the form of Critical Race Theory, Multicultural Studies, and AfroCentrism, where conventional methodology, under the guise of neutral and even scientific inquiry producing truth, has been tortured to spawn whole sheets of subtly and damaging discriminatory inquiries and standard-setting.

But perhaps the most frequent and pernicious intellectual/academic strategy in the present period, in approaching the wages and badges of slavery under a conservative drumbeat, is a determined attempt to undermine the moral position of African-heritage peoples in the present day be assigning them increasing shares of responsibility of the institution and conduct of African slavery itself.

This is done by a combination of channeled, detailed research plus a certain kind of interpretation, which, combined, have the effect of relativizing the blame for an historically acknowledged historical evil, as will be indicated herein in the discussion about natural law and slavery.

There is of course nothing wrong with detailed research, but writing history is a synthesis of details and choice of emphasis - and omissions, however small - to sustain a narrative and/or path of analysis. The aim of much of such present research on African slavery seems to lie in two directions:

(1) African slavery is only one example and phase in an ancient human practice of slavery, and must therefore be understood and discussed in that context; since there is nothing really unique about the African slave trade when placed in that context, any differences are mere historical details without meaning, and certainly without moral meaning.

(2), detailed research now reveals the extent to which African traders, sovereigns, and others cooperated and collaborated in the African slave trade in selling ‘their own people’ to the Europeans.

These findings at the very least purport to justify a sharing of any moral blame falling upon Europeans with Africans and their heritage successors. In addition, for some scholars, the findings justify erasing any European responsibility altogether in the name of notions of personal responsibility (as opposed to historical forces set in motion) and commercial market forces. To make the latter arguments work, imposing notions of personal responsibility of Africans to create an estoppel against African-American claims of European historical responsibility is crucial. And to do this, one must - for Africans and black-related historical issues - adopt a very paternalistic approach to history, but only for this category of questions, which violates much historiography about analyzing historical imperatives and the movement of events otherwise. Every African now becomes a ‘great man of history’ for this purpose’. . . .

For the African slave trade, it is simply maliciously foolish to even imply a position that assigns responsibility to African heritage peoples for the collaboration of a relative few of their numbers at the African source of the trade, compared with the estimated 20 million that were taken to be slaves and the 12 or so million actually transported to the Americas. It is malicious in the face of overwhelming evidence of European intent and consciousness of their actions, but especially in the face of the undeniable and copious facts from every source of the consistency of African rebellion on all levels and in all venues against being enslaved. It is as close to a record of mass collective heroic desperation through three centuries as exists in all of human history, and it cannot be washed away morally or empirically by showing the details that this people were human after all. And therefore, among their numbers, some were not heroic enough to resist overwhelming imperatives around them that penetrated their own minds, such as greed, patterns of war, and temporal personal advantage. The history of African slavery and the slave trade to the New World is the history of African opposition and rebellion to slavery, so clearly that moral responsibility for the international slave system can only fall upon its perpetrators and those groups who consistently have benefited from it and subsequently its wages and badges.

Thus one may have questions about the previously cited quote of Professor Thomas, which seems to imply that African tribes were so atomized that the seizing of slaves from one to another to sell for the ships was assuaged among Africans by overwhelming feelings of narrow tribal hostility, alienation, and a lack of perspective beyond elite self-advantage. This implies that generally Africans did not perceive nor really care what was happening to them collectively. Even if such could be documented beyond doubt, it does not answer the historical questions of outside forces aiming to set patterns of intra-group conflict in motion in Africa precisely to cause slaves to be delivered for traded European goods, as was the case. The same outside forces then actually reduced the captives to slaves by their own hands on their own ships in their own colonies. Such subtle points of emphasis in a generally valuable work must be identified as par of a very large overall problem confronting African-heritage people today, including the validity of the interpretation of its own history.

Thomas concludes that in West Africa, slaves seem to have been the only form of private property recognized by customary law, ans also the most striking manifestation of personal wealth.

That solution rested firmly and destructively on the backs of not only the slaves themselves, but also of especially on West African kingdoms, clans, and tribes. . . . It was, with pervasive and deliberate European facilitation, encouragement through bartering of European goods that became African necessities, and coercion throughout the process - not least in the introduction of firearms into Africa. . . . As Franklin and Moss have noted, the vast majority of slaving was to be carried out in West Africa where civilization had reached its highest point on the Continent except possibly for Egypt. Only the best built, healthiest, most spirited, and most identifiably intelligent of African men, women and children were commercially desired as slaves for the New World, and thus they were brought to the ships over the next two and on-half centuries in the millions. . . . These African slaves newly in the New World appeared . . . to mount the first New World slave revolts. Uprisings occurred - the main objectives appeared to be either to escape from slave confinement, or to overthrow the colonial government with the help of allies - in 1522 in Hispaniola, 1523 in Mexico, 1527 in Puerto Rico, 1529 in Colombia, 1533 in Santa Domingo, and 1537 in New Spain. Smaller revolts were reported in Caragena in 1545, Santo Dominga again in 1548, and Panama in 1552. . . .

By 1600, several trends were becoming apparent that would continue for more than two more centuries relative to African resistance and opposition to being enslaved. . . . The first was that Africans captured in Africa for the slave trade largely began to resist from the beginning, even before being taken aboard the slave ships. There were mutinies, struggles, suicides, and ferocious attempts to escape at every step of the way, along with the constant possibility that Africans being ferried out to the slave ships from shore would jump overboard to escape or drown themselves. . . .

The Portuguese made a weak attempt to resolve the morality question through legalistic strategies. After deciding that their direct kidnapping of Africans for slavery was generally more trouble than it was worth, they decided thereafter to induce by trade and barter African middlemen to provide them slaves for sale. . . . This response to slavery as a contentious moral issue in Spain and Portugal, as we have already seen, in the last analysis must be understood as a justification for a commercial imperative to continue on European terms. Only a legal fig leaf under crude principles of quasi-contract was thrown at the situation to overcome what was possibly by many Europeans perceived, consciously or unconsciously, as a troublesome moral position in resisting their European-manufactured fate stated by the unfortunate African captives.

Second, during this period both Spanish settlers and the sovereign realized that the demand for slaves, especially for the sugar plantations in the Caribbean and in Central American territories, was generating so great a rate of importation from West Africa and also from Europe that in many colonies the numbers of resident African slaves outstripped, sometimes substantially, the numbers of white settlers. This was increasingly perceived as a dangerous security problem, precisely because it could not be pretended that Africans were happy with their fate, and because it was early discovered that Africans had organizing abilities. Despite differences in language and sub-culture, slaves had the wherewithal to mount various forms of resistance not excluding full-scale revolt, especially as they realized they were in a local majority. This was a constant European settler fear, which antedated the same general fear by the end of the 17th century in the southern British colonies, e.g., the Carolinas, on the North American mainland. And as the above-mentioned patterns of revolts and uprisings and other forms of opposition show, which list could be lengthened considerably, African slaves gave them ample reason for their fears.

Here, horrific tortures and punishments, supposedly legalized by being written into local and sovereign slave codes - notwithstanding the Spanish sovereign law’s preserving in theory the humanity of the African slave - were the primary European response to their security fears throughout all the Americas, a commonality of the international slave system.

Notwithstanding this pattern of what must be counted as among the most ghastly patterns of official personal tortures in human history, African slaves in all these territories continued a consistent pattern of opposition, sabotage, escape and revolt. Undoubtedly the prospect of such inhuman deterrence measures caused Africans across-the-board to think strategically about their own best interests. Hence there ares some instances of slaves . . . joining with slaveholders to fight off outside invaders. The need of African-heritage peoples for strategic thinking should be kept in mind for our later discussion about African slaves and free backs in the American revolution.

The third historical trend of slave resistance is that by 1600, the impulse of many African slaves fleeing their enslavement to form maroon communities - settlements of escaped slaves in remote areas in an attempt to construct permanent or long-lived free communities outside of the international slave system - had become apparent. . . . In concept and action maroons or maronage struck at the heart of the international slave system. . . . Its existence tangibly called into question the moral legitimacy of slavery as an international enterprise, whether or not the connected history of opposition and rebellion at the slave departure points had already done so, no matter what the commercial need for it. Whatever the justifications that were cooked up to support the slave system’s functioning, the consent in any meaningful sense of the vast majority of Africans enslaved could not be cited to confirm either its legitimacy or its legality.

That system then had to be supported by legal rules and doctrines imposed on the actors whom the system was attempting to regulate. Such ‘law’ had to rest on principles of sufficient authority to override the consistent and tested desires of the large captive numbers of human beings palpably to the contrary, over a long period. As an example of law-in-action, the international slave system crossed the line from ‘law’ to the application of massive coercion by one against another, for its own sake and without authority.

McDougal and Lasswell elsewhere have analogized such a situation masquerading under legal forms as being no more than banditry. This may be one contributing factor to the historical observation that slavery never really became universally morally accepted; in virtually every community , not least the United States dating from before the founding of the country, there was moral unease and uncertainty surrounding it in and among controlling white groups.” pp. 16-17

Early Trends in International Law

“R. P. Anand has reminded us that part of the history of any chain of events is the continuous struggle to evolve ‘principles of law for ever-growing purposes.’ . . . It is also true for both the evolution of national community processes of law and for international law. Regarding the latter, this evolution cannot be restricted to the sovereigns and national central governments that, under the reigning legal doctrines of the period are promised, as an outcome of this struggle, to have standing (i.e. recognized legal capacity) to formally raise their rights and interests in courts, formal treaty negotiations, and other appropriate arenas.

Rather, any consideration of the evolution of international law in connection with historical trends - including the spreading of the international slave system into the North American colonies - must equally consider those groups, peoples, tribes, genders, races, and even individuals who during the same period, in terms of power, wealth and dominating influence, may have been subordinate to the above sovereigns and national elites. It must consider these latter who, while subordinate, were a clear and intense focus of international concern by dominant legal decision makers, because of the impact and dependency of their existence, presence, actions and potential or feared actions on the interests and wishes of those sovereigns and elites. . . .

Thus we must ask, rather than simply take it as an unexamined fact, why sovereign and other elite groups were the beneficiaries of evolved international principles of standing, legal personality, and other preferred status of participation in legal decision making, and not other groups, entities and peoples who were the intense and continuing focus of the concerns and objectives of these elites. On these the latter depended for the accomplishment of their collective value-aims. We must equally ask, what demands, claims, and interests did these subordinated peoples and groups have and make in this historical struggle to evolve international legal principles, even as colonial elites were being careful to deny them formal access to legal arenas? Neither lack of formal access nor lack of defined rights in colonial law can be taken as synonymous with having no interests or claims to make to, or stake in the operation of the same legal process which bars them. This is especially so as the latter tries to control the allocation of value-benefits in their collective and individual lives including, indeed, often whether they live at all.

Yet, notwithstanding the foregoing, the legal history of international law and American legal history have treated most African-heritage peoples as objects and not subjects of law when they have not ignored them altogether. Such legal history has been written to equate African-heritage peoples’ lack of standing and legal personality in this historical struggle to evolve legal principles with a lack of capacity, intelligence, consciousness, and perception to define interests and push claims and advocate rights under the same law. This is especially the case for international law which evolved during this same historical period of the 16th through the 18th centuries. As will be seen throughout this work, these questions define the evolving international legal situation of black Africans generally in the New World, those twelve or more millions reduced to slavery as they were kidnapped from their homeland, and brought in chains to the New World - the Caribbean Islands, Central and South America, and the British colonies of North America -to be slaves in perpetuity. . . .

Finally, as discussed above, the history of New World slavery is the history of slave revolts and opposition at every step of enslavement and its maintenance, beginning with kidnapping battles in the African bush as the first step to the slave ships, to the suicides and mutinies attending the Middle Passage over the centuries, to revolts, running away, and maroon communities in the New World. This is an integral part of the historical struggle in the New World underlying the evolution of international law. Thus such opposition and revolts must be integral to any understanding of not only legal principles, but the interests and claims of African-heritage peoples, and particularly of African-Americans to international legal principles. Considerations of legitimacy are inevitable through the consent of the governed, justice and human dignity as moral and legal expressions, the extent to which group domination may be reflected in a moral jurisprudence, minimum public order through stability under law as among either sovereigns or citizens, and the evolution of international law as a reflection of international capitalism. None of these notions can be contemplated apart from understanding that enslavement in the New World was synonymous with Black opposition and revolt in all its forms and with the claims flowing from that continuing resistance.”

Early Trends in International Law

“During this general period of the 16th through the 17th centuries there was a debate in Spain and to some extent in Portugal, carried on largely in ecclesiastical circles, about the morality of slavery. . . . Many of these questions arose in a notable public face-off at Valladolid in 1550 between Bishop Las Casas and the classicist Gines de Sepulveda on the subject of how the Catholic faith could be preached and promulgated in the New World. The proceedings included Fary Domingo de Soto, the most distinguished pupil of the recently deceased great early international legal jurist Francisco de Vitoria. . . . .

However, in 1557, de Soto published his Ten Books on Justice and Law in which he argued that it was wrong to keep in slavery a man who had been born free, or who had been captured by fraud or violence - even if he had been fairly bought at a properly constituted market. . . . Alonso de Montufar, archbishop of Mexico . . . wrote to King Phillip II in 1560: ‘We do not know of any just cause why the Negroes should be captives any more than the Indians, because we are told that they receive the gospel in good will and do not make war on Christians.’ Philip does not seem to have answered . . . . the legality of a license to a banker to transport 23,000 African slaves to the Americas . . . .

At about the same time, in 1554, a Portuguese captain and military writer, Fernao de Oliveira, criticized the slave trade in his Art of War at Sea. Anticipating some of the arguments of the later abolitionists movement, de Oliveira noted that the African rulers who sold slaves to the Europeans usually got them by robbery or by waging unjust wars. But no war waged specifically to make captives for the use of the slave trade could possibly be just. Oliveira denounced his countrymen for inventing ‘such an evil trade’ as the ‘buying and selling of peaceable freemen as one buys and sells animals,’ with the spirit of a ‘slaughterhouse butcher.’ These arguments were followed in 1560 by the work of another Spanish Dominican, Martin de Ledesma, who argued in his Commentaria that all who owned slaves gained through the trickery of Portuguese traders should free them immediately, on pain of eternal damnation. He also noted that Aristotle’s comments about wild men living without any order could not apply to Africans, many of whom lived under regular monarchies [Siphiwe note: or non-state order such as the Balanta]. . . .

The line between kidnapping and war was a thin and wavering one; the traders themselves continued to maintain that in buying slaves they were serving the best interests of humanity. However another, longer term result of these arguments was that they were joined and built upon by later legal scholars. . . . They would wrestle with the question of whether the conduct of the international slave system and slavery itself imposed any limitation on the authority of sovereigns and their agents, beyond that exercised from time to time for the systems-maintenance objectives of treating slaves sufficiently decently to maintain the efficiency of their labor where European settlers most desired it.

Indeed Thomas notes other attacks on the slave trade by Spanish and Portuguese clerics writing in the mid-16th century. These went so far as to question what had been a basic justification, namely slaves’s status as prisoners of war. In 1573, in his Arte de los contratos published in Valencia, Bartolome Frias de Albornoz, a Spanish lawyer who had emigrated to Mexico to become its first professor of civil law and is now considered ‘the father of Mexican juisconsultants,’ argued in effect that prisoners of war could not be legally enslaved. He thought that no African could benefit from living as a slave in the Americas, and that Christianity could not justify the violence of the trade and the act of kidnapping. The implication was that clergy were too lazy to go to African and act as real missionaries. . . . Albornoz’s book was condemned by the Inquisition as being unduly disturbing.

These serious doubts were, in effect, answered, in the form of a revelation. A Dominican friar, Fray Francisco de la Cruz, told the Inquisition in Lima, that an angel had told him that ‘the blacks are justly captives by reason of the sins of their forefathers, and that because of that sin God gave them that color.’ The Dominican explained that the black people were descended from the tribe of Aser, or Isacchar, and they were so warlike and indomitable that they would upset everyone if they were allowed to live free. This answer to Albornoz indicates that the process was already well underway among a wing of Spanish intellectuals in the 16th century to use Christian doctrine to justify the slave trade, and particularly to characterize African blacks as an inferior and dangerous ‘Other’ who deserved enslavement. . . .” [Siphiwe Note: this goes all the way back to St. Martin of Braga, a Christian that considered all non-Catholic Christian beliefs as the work of the Devil, who in 579 who wrote De Correctione Rusticorum

Considerations of Legal Evolution

“Let us try to put this in some context during the 16th and 17th centuries of both the evolution of international law and the rise of the slave trade. . . . This period saw modern international law being pulled together as a coherent legal system, principally through the work of the brilliant Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius, writing in the early 17th century. Grotius built this legal system, or at least its first model, from a mixture of existing and classic principles, including, as Anand points out, a knowledge and respect for Asian state practice regarding the universalism of international law and notions of freedom of navigation and trade. Grotius grounded the jurisprudential basis of this new international law on principles of natural law out of the scholastic tradition, but natural law as founded not so much on the law of God as on principles of right and universal reason found throughout the human community. He was doing so, however, out of a jurisprudential debate already growing as to whether international law should be grounded on natural law or on the prerogatives of each and all territorial sovereigns. To shorten a longer story, this debate had begun even before Grotius’ major work in 1625, and it picked up steam thereafter through the works of contending European scholars such as Selden and others. This debate foretold the shift that international law would indeed make from being grounded on natural law to being grounded on territorial sovereignty, a shift indicated by the work in about 1750, of Emmerich Vattel, a Swiss scholar, even though he continued to pay lip service to natural law as part of the international legal foundation. Vattel’s work would be cited into the early 20th century as authoritative, and he laid part of the basis for international law being defined through the school of legal positivism. For African people brought as slaves into the New World, this shift was potential of great importance.

Understanding Legal Positivism

Legal positivism is a philosophy of law that emphasizes the conventional nature of law—that it is socially constructed. According to legal positivism, law is synonymous with positive norms, that is, norms made by the legislator or considered as common law or case law. Formal criteria of law’s origin, law enforcement and legal effectiveness are all sufficient for social norms to be considered law. Legal positivism does not base law on divine commandments, reason, or human rights. As an historical matter, positivism arose in opposition to classical natural law theory, according to which there are necessary moral constraints on the content of law.

Legal positivism does not imply an ethical justification for the content of the law, nor a decision for or against the obedience to law. Positivists do not judge laws by questions of justice or humanity, but merely by the ways in which the laws have been created. This includes the view that judges make new law in deciding cases not falling clearly under a legal rule. Practicing, deciding or tolerating certain practices of law can each be considered a way of creating law.

Within legal doctrine, legal positivism would be opposed to sociological jurisprudence and hermeneutics of law, which study the concrete prevailing circumstances of statutory interpretation in society.

The word “positivism” was probably first used to draw attention to the idea that law is “positive” or “posited,” as opposed to being “natural” in the sense of being derived from natural law or morality.

In jurisprudential terms, natural law as the basis of international law provides a normative basis for criticizing the actions of a sovereign towards those people in his or her territory, in part because the rights of such people are through natural law inherent to their existence, and not given by the state. From the time of the classical Greeks there has always been some kind of slavery, and under natural law it has been generally seen as wrongful. But simultaneously natural law doctrine has always been hard pressed to explain and encompass the continuation of slavery and other wrongs under the laws of the human community, notwithstanding their wrongfulness. Slavery has long been a touchstone of the struggle between right principles and bad actions, as symbolized by that between natural law as the basis of the law of God or right reason, and the law of humankind as symbolized by the persistence of slavery and other wrongful policies.

The battle over the rightness of slavery continued to be joined with the resurgence of European and trans-Saharan slavery beginning in the 12th century, as discussed earlier. . . . But with the outbreak of virulent New World slavery to serve the labor demands of international capitalism, the stakes in this battle rose considerably. One part of the answer to this clash in legal history is the above shift of international law in its basis to territorial sovereignty, thus removing any outside normative platform from which to criticize the sovereign. This was because obligations on such sovereigns could then only be fixed in law with their consent. To be clear, I am not saying that New World slavery caused this jurisprudential shift in international law, or perhaps more accurately made it impossible for Grotius’ view to hang on after the Treaty of Westphalia, ending the Thirty Year’s War in 1648. I am saying that insofar as the rise of the modern state system is bound up with the rise of international capitalism into the New World, this jurisprudential shift benefited the sovereigns and their merchants and colonial settlers in instituting slavery and promulgating what can fairly be called an international slave system, stretching from Europe throughout the breadth of the Americas. One major doctrinal and normative benefit to that system was, as international law slid onto a territorial sovereignty foundation,

that the institution of slavery could not be frontally challenged under that law because there was increasingly no non-sovereign basis in principle from which to do so.

We have seen, and will later see further, that this period featured the rise of the great European empires - the Spanish, the English, the Dutch, the Portuguese - and that a key dynamic was the expansion of all of these sovereignties into the New World. . . . With the establishment of European colonies in the New World, beginning with the Spanish in the mid-16th century, and the Spanish debate about the lawfulness and morality of enslaving indigenous Indians throughout the Americas, the question arises of the early sources of international law. Specifically, the extent to which those sources could be said to include what might be called ‘intra-Empire law’ from the 16th into the 18th century. The question is framed by the fact that in the New World, under doctrines of discovery and conquest, the international process of colonialism got under way be each of these European sovereign states placing virtually all of the America’s territory under their respective jurisdictions. Equally, once such colonies were in place there was a process established, necessarily, of shipping for vital communication and protection with the European metropolitan sovereign and among New World colonies, of the same sovereign. All this shipping was under the general lawmaking sovereign authority of the metropolitan. . . .

The question accordingly becomes, what was the influence of intra-empire law, particularly that of Spain and England, on the development of international law as the latter affected the situations of African slaves and the small numbers of free blacks in the New World? Issues arise such as:

Did slaves have rights under international law?

Did sovereigns have a duty to put limitations on the treatment, e.g., punishment, of slaves by masters?

Did sovereigns have duties to each other to honor the international or colonial trade and other intra-empire arrangements made to continue or regulate the slave trade and slavery?

Did the clash between natural law and sovereign territorial perspectives relative to the development of international law affect any rights or duties of slaves and masters?

What was the relationship between the exercise of jurisdiction by the sovereign over its colonies, or lack thereof, and the rights of slaves relative to either local slave codes or rights sounding directly under international law?

What rights did slaves in the North American mainland British colonies have beyond those (not) granted by local colonial law and slave codes, such as in the colony of Virginia?

To illuminate some of these questions, we might briefly consider, for example, any comparative insights gleaned from contrasting Cuban slave codes in the 16th century forward under the Spanish empire with those of Virginia under the British Empire.

One might think that, in the growth of international law and the international slave system, black African slaves, especially in north America, would be more benefited and protected if scholars such as Grotius and Pufendorf in the mid-17th century had prevailed in the European jurisprudential tussle, and the basis of international law had remained some effective version of natural law. A normative standpoint from which to judge the sovereign about instituting and establishing a system of slavery would have been preserved. However, the legal history of the Spanish slave codes as compared with the Virginia slave code raises the possibility that more state sovereignty, not less, would have been beneficial to black slaves. Particularly, the continuous exercise of authority by the Spanish Crown in its colonies, including Cuba, on questions of rights and duties of slaves and slavemasters, inserted the state as a buffer between local slavemasters’ abuses of slaves, and the level of basic control and security needed to keep the Spanish slave system running and producing wealth at acceptable levels. By inference, this meant the international slave system , as well. In doing so, the Spanish sovereign made it clear that the legal personality of the slave as a human being was to be preserved, along with certain minimal rights that were basic to this conception.

In comparison, the Virginia slave codes, beginning in 1660, reduced black African slaves to chattel and gave him and her no rights of legal personality (except in bringing them to judgment for rebelling), because in part the English Crown exercised no authority under British law to review those slave codes. Furthermore, no slave codes in any other North American colony would be reviewed although the doctrinal authority was available to London to do so, e.g., through Orders-in-Council. This lack of exercise of authority by the British Crown, coupled with the general philosophy of individualism (for whites), in the context of expanding New World international capitalism, gave Virginia colony the unreviewed discretion to treat its slaves as economic units, with no countervailing rights for slaves or duties of masters. The state was not available as a buffer to guarantee the legal personality of slaves as human beings. Racism and capitalism thus reigned supreme, particularly in the southern North American colonies.

Here, the state must be distinguished from colonial elites who were both slavemasters and local legal decision-makers. The latter, were, relatively speaking, the major immediate source of abuse of slaves in that territory, though the Spanish slave codes prescribed horrendous punishments in those circumstances identified as a threat to the basic system. Slaves in Virginia were subject only to whatever the twisted imagination of slaveholders could conjure up by way of making the protective duties of masters and rights of slaves nil and the prerogative of masters to control and punish slaves absolute. Virginia slaves, given the immediate consciousness and organization, might have pressed claims to London to exercise its authority to preserve their humanity as a matter of law. This would have been a claim to somewhat more beneficial ‘outside law’, but id did not happen. As discussed later, slave results did happen.

The Spanish slave codes at least preserved the legal humanity of its slaves because they retained a basic continuity with the Scholastic tradition as a foundation of natural law. But this also bought into the traditional difficulties of natural law jurisprudence. Thus the codes were bifurcated in policy between ‘slavery as a necessary evil,’ and ‘making slavery effective in the colonies according to colonial conditions.’ Here natural law depended on the state to enforce its writ on preserving the humanity of the slaves (though not on their treatment across the board), because it was clear that left to their own wishes and impulses slaveholders and local colonial officials would not. This latter is proven by the English/Virginia experience and the horrific punishments prescribed for slaves with large dollops of discretion to white slave holders to adjudge, decide, and administer them. In this sense, the Spanish sovereign felt bound by natural law, but struck the policy compromise with human law well short of abolishing slavery: it was an evil, but a necessary one. The horrific punishments included here were prescribed in a rational framework by the metropolitan sovereign. . . .

But Spain’s codes did not provide a normative standpoint to challenge the institution of slavery per se. It only provided a somewhat less harsh - overall - functioning of that part of the international slave system under Spanish control. And judged by the prevalence of maroon communities and other forms of slave rebellion, for African slaves ‘a more humane slavery’ was not tolerable, neither in theory nor in practice.

Considerations of Legal Evolution

“And, as mentioned before, they necessarily, in the name of their own settlers’ and investors’ (financial) security shared a common interest in preventing slaves from rebelling or running away, much less forming independent African states. They shared an interest, as well, in preventing them from taking local power and in preserving them collectively and individually for their property value as efficient economic units of production. There was thus a premium on the general alliance among local governments in the colonies effective at suppressing slave rebellions, among settlers in employing whatever means to make slaves work, and among sovereign states in supporting both of the above for the benefit not only of large investors but for the income flowing directly into sovereign treasuries.

This objective to ensure the functioning of that alliance, and thus to coordinate resources, including at times military resources, to maintain anti-slave security across the breadth of the entire international slave system can only be seen as a key factor in maintaining minimum international order. That includes doing so through sovereign objectives under international law, during this period. Again, we note the especial attention colonial authorities in all colonies gave the question of maronage, not only for the local disruption caused by the establishment of such groups and/or communities, but equally because in doing so, African slaves were undermining the moral and theoretical foundations of the slave system. Nothing that these sovereigns, settlers, and elites could do to deny slaves standing in local and international fora and courts, to characterize them as non-human chattel and treat them as property, could ever diminish (1) their certain knowledge that the majority of Africans hated their enslavement. Nor could these tactics and attitudes diminish (2) their well founded international paranoia that each body of these slaves no matter where in the Americas they were located, no matter how harshly or (comparatively) leniently they were treated under local law and practice would, over time, be constantly working on a number of levels, on the other side of a rather vast racial and cultural divide, to free themselves and, that they had considerable abilities to do so. For about three centuries (1) and (2) comprised a major international problem.

Accordingly, there was no doubt that African slaves and then their heirs and successors had then, and retain to this day, a considerable interest in resolving questions about the evolution, interpretation, prescription, application, enforcement, and effects of international law, and their role in it. To understand this interest further is our goal here.