Every May 25th, people of African heritage all over the world celebrate African Liberation Day, founded in 1958 when Kwame Nkrumah convened the First Conference of Independent States held in Accra, Ghana and attended by eight independent African states. The 15th of April was declared "Africa Freedom Day," to mark each year the onward progress of the liberation movement, and to symbolize the determination of the people of Africa to free themselves from foreign domination and exploitation.

Between 1958 and 1963 the nation/class struggle intensified in Africa and the world. Seventeen countries in Africa won their independence and 1960 was proclaimed the Year of Africa.

In the United States, In 1962, after a conversation with Malcolm X, Max Stanford founded the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), the first group in the United States to synthesize the thought of Marx, Lenin, Mao, and Malcolm X into a comprehensive theory of revolutionary black nationalism. The Black Guard was a national armed youth self-defense group run by RAM that argued for protecting the interests of Black America by fighting directly against its enemies.

On the 25th of May 1963, thirty-one African Heads of state convened a summit meeting to found the Organization of African Unity (OAU). They renamed African Freedom Day "African Liberation Day" and changed its date to May 25th. These new African nations fought armed liberation struggles against their foreign oppressors.

In 1964, Malcolm X became a RAM officer. He then traveled to Ghana and met with representatives of liberation organizations, including the African National Congress of South Africa (ANC) and the South African Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC). After returning from Ghana, Malcolm X and John Henrik Clarke formed the Organization of Afro American Unity (OAAU) on June 28th, 1964 to represent the African American liberation movement. On July 17, 1964, Malcolm X (traveling with Milton Henry) was welcomed to the second meeting of the Organisation of African Unity in Cairo as a representative of the OAAU. During this time, Malcolm X deepened his relationship with the forces of liberation in Africa while living on a boat in the Nile with all the liberation organization leaders. Said Malcolm,

“I was blessed with the opportunity to live on that boat with the leaders of the liberation movements, because I represented an Afro-American liberation movement - Afro-American freedom fighters. . . . It gave me an opportunity to study, listen and study the type of people involved in the struggle - their thinking, their objectives, their aims and their methods. It opened my eyes to many things. And I think I was able to steal a few ideas that they used, and tactics and strategy, that will be most effective in your and my freedom struggle in this country.”

In the book, From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity, William Sales, Jr. notes,

“Paralleling these discussions, and in as much secrecy, were discussions Malcolm X had with RAM through its field secretary, Muhammed Ahmed. As Ahmed remembered it, in June 1964 he and Malcolm worked out the structure of a revolutionary nationalist alternative to be set up within the Civil Rights movement. They also outlined the role of the OAAU in this alternative.

‘The OAAU was to be the broad front organization and RAM the underground Black Liberation Front of the U.S.A. Malcolm in his second trip to Africa was to try to find places for eventual political asylum and political/military training for cadres. While Malcolm was in Africa, the field chairman [Ahmed] was to go to Cuba to report the level of progress to Robert Williams. As Malcolm prepared Africa to support our struggle, ‘Rob’ [Robert F. Williams] would prepare Latin America and Asia. During this period, Malcolm began to emphasize that Afro-Americans could not achieve freedom under the capitalist system. He also described guerrilla warfare as a possible tactic to be used in the Black liberation struggle here. His slogan ‘Freedom by an means necessary’ has remained in the movement to this day.’

These discussions, in fact, reflected the impact of Malcolm’s interaction with the representatives of national liberation movements and guerrilla armies during his trip to Africa. He was very much focused on establishing an equivalent structure within the African American freedom struggle. On June 14, 1964, the Sunday edition of the Washington Star featured an interview with Malcolm X in which he announced the formation of ‘his new political group,’ the Afro-American Freedom Fighters. In this interview Malcolm X emphasized the right of Afro-Americans to defend themselves and to engage in guerrilla warfare. A change of direction was rapidly made, however. As Ahmed reported, Malcolm’s premature public posture on armed self-defense and guerrilla warfare frightened those in the nationalist camp who feared government repression. They feared giving public exposure to organizing efforts for self-determination and guerrilla warfare. Malcolm agreed, and the name of the new organization became the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

The OAAU was to be the organizational platform for Malcolm X as the international spokesperson for RAM’s revolutionary nationalism, but the nuts and bolts of creating a guerrilla organization were not to take place inside the OAAU. The OAAU was to be an above-ground united front engaged in legitimate activities to gain international recognition for the African American freedom struggle.”

Then, on February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated. However, the armed African American liberation struggle had already begun. Like the black people on the African continent, black people in America were struggling to establish a nation of their own.

In August of 1965, Robert F Williams, living in exile in Cuba, published an analysis on the Potential of A Minority Revolution in the USA.

On March 31, 1968, the Malcolm X Society (led by Milton Henry now called Gaidi Obadele) convened the Black Government Conference held in Detroit, Michigan. Attended by a few hundred people, the conference announced the formation of the Republic of New Afrika (RNA), which was to be composed of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. The Conference participants drafted a constitution and a declaration of independence. To fund the RNA, organizers planned to negotiate with the United States for reparations and for status under the Geneva Convention and by conducting a UN Sponsored Plebiscite for Self Determination.

This is a critical part of African American history that is little known and rarely given serious study. As a result, most people, including African Americans themselves, don’t even know that at the same time that African people were fighting and winning liberation struggles to achieve nationhood, African Americans were fighting the same liberation struggle AND LOST.

AS A RESULT, AFRICAN AMERICANS DID NOT ACHIEVE LIBERATION, FREEDOM AND NATIONHOOD.

Given the incredible unity of black people in and outside of America, as well as the international attention and support by the international community, the legitimate claim to establish a a black nation for African Americans on territory currently held by the United States government, MUST BECOME PART OF THE CONVERSATION FOR PROVIDING JUSTICE TO AFRICAN AMERICANS. IT IS AN ABSOLUTE REQUIREMENT, FOR AS WE HAVE BEEN SAYING,

NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE

Unfortunately, the legitimate voice of the Black Nationalists are not being featured in the media and there is little understanding of the black nationalist’s claims which are almost always dismissed as ridiculous by people, both black and white, who have never seriously studied it.

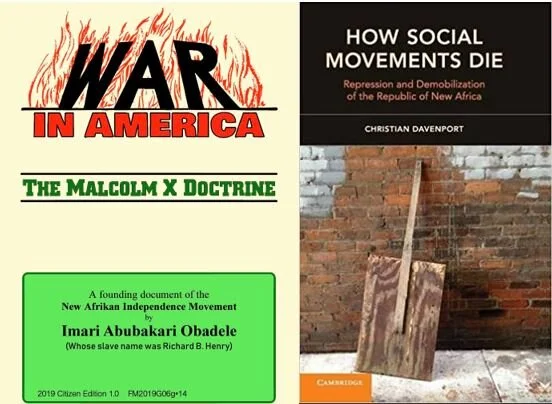

Therefore, below is reproduced War in America, one of the foundational documents of the Republic of New Afrika laying out in great detail the rationale and strategy for a black nation seceding from the United States of America. There has never been a more opportune time for liberating black people in America from the jurisdiction of their oppressors in the land of their captivity.

THE SOLUTION TO AMERICA’S RACE PROBLEM IS SIMPLE: RELEASE THE BLACK PEOPLE FROM UNITED STATES CONTROL. FREEDOM MEANS CONTROL. WHEN BLACK PEOPLE HAVE CONTROL, IN THE FORM OF STATEHOOD, THEN THEY WILL BE FREE. UNTIL THEN, AS CITIZENS WITHIN THE NATION THAT ENSLAVED THEM, CITIZENSHIP DOES NOT MEAN FREEDOM. IT MEANS YOUR STATUS HAS BEEN CONVERTED. BLACK PEOPLE ARE STILL CONTROLLED BY FOREIGNERS AND A GOVERNMENT THAT SPONSORS TERRORISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES AGAINST BLACK PEOPLE BY FAILING TO PROSECUTE VIOLATORS AND MAINTAINING CONDITIONS BEST DESCRIBES AS GENOCIDAL.

Now it is time for every black person to revisit the Republic of New Afrika’s strategy for liberation as well as an analysis of what happened.

Continue reading…

Introduction To Revised Edition

THE most significant achievement of the Black Revolution since the publishing of War In America in January of this year was the founding, on March 31 of this year (1968), of the Republic o f New Africa.

Nothing else, in a year already full of significant events in our struggle, called for a revision of any concept contained in War. All the other events — the assassination of the leading exponent of non-violence, even the significant turning brought about by the victory of guerrillas in Cleveland who in July outgunned oppressive police and slew three of them — all the other events fit easily into the broad pattern stroked out by the original version of War.

But the founding of the Republic o f New Africa called for revision of a basic concept: War, written a year and a half before the founding, envisioned that the Malcolmites would work within the governmental framework and state structure of the United States, winning black people, first in Mississippi, to the cause of independent land and power, follow this with election victories (the sheriffs’ offices, particularly) within the U.S. federal system, and finally, take the black state out of the U.S. federal union at the moment when white power could no longer be successfully resisted or neutralized in its efforts to prevent the creation of a new society in the black state.

The founding of the Republic obsoleted this approach — and this revision of War makes note of that obsoleteness. By declaration the nation has become a fact — though subjugated by the United States. It is no longer possible, if we are a nation as we have declared — and we are — to proceed through the framework and state structure of the United States federal union. Our job becomes not winning sheriffs' elections but, rather, simply demonstrating that our government, the Republic o f New Africa, does in fact have the consent of the people who live in the areas we claim as subjugated territory of the Republic o f New Africa. The job is that of demonstrating that we — not the government of the United States — have the consent of the people.

Why, then, since the Malcolm X Society had stated the former approach as our position, did we change direction, taking the lead in founding the Republic o f New Africa?

The answer is simple. It was to remove the Malcolmites and the other black nationalist revolutionaries in America from a position where the United States might with impunity destroy them to a position where attacks upon us by the United States become international matters, threatening world peace, and thereby within reach of the United Nations, thereby within reach of our friends in Africa and Asia who would help us. We could not entertain hope of help in our struggle from international sources so long as we conducted our struggle within the United States federal union and as if we were citizens of the United States (black people are not and have never been citizens).

The Republic was brought about, when it was, to frustrate hostile action of the United States against the seekers of land and power for blacks on this continent, and to create proper safeguards for ultimate success.

BROTHER IMARI Detroit, Michigan, Subjugated Territory of the Republic of New Africa

20 August 1968

Introduction

OF the three brothers who bear witness for Malcolm X — known, as we were, by our slave name, the Henry brothers — only Milton was sure from the beginning. I was the last to come to the realization that it was he “who should come” and that there was no need to “look for another.”

I personally saw and spoke to Malcolm X on only four occasions. Once was in Washington, in the lobby of the headquarters hotel just before the 1963 March on Washington; another time, shortly before, was in the Shabazz Restaurant in Detroit. Each time Malcolm smiled, shook my hand and spoke with that characteristic courtesy and brotherliness, but I am sure he did not know me and certainly did not recall me from one meeting to the next. Twice more we were to meet: once, short days before the death of John Kennedy (November 1963) when he came to Detroit to address a rally sponsored by the civil rights group (GOAL — The Group On Advanced Leadership), of which I was president, a moment when Malcolm’s popularity with the Muslim rank-and-file was at an all-time high and he was still within Elijah Muhammad’s “Nation of Islam.”

The last time was a year later, February 14, 1965, the day his home in New York was fire-bombed, one week before his assassination; he came to Detroit, despite the firebombing, to speak at a rally to which Brother Milton and Brother Ajay, owners of the Afro-American Broadcasting Company, had invited him. On this occasion Malcolm had departed Elijah’s “Nation of Islam”; he was sure of his own death to come, magnificently unconcerned but prepared, certain that either Black Muslim enforcers, doing the bidding of Elijah Muhammad, or agents of the United States 3 government would soon succeed against him personally, where both had failed before. We talked at length in his hotel room; I was anxious that we should give national form and specific programmatic direction to the new movement that his break with Elijah signaled. He assured us that it would come. And, when he gave up his life in New York the following Sunday, we were left, I felt, without that direction.

Of course that was not true.

All that we should do, Malcolm had already set out before us. It was left but for us to organize and carry out the work.

So here we come: the Malcolmites, laboring with and speaking for the young black mass who, with more debt to Malcolm than they realize, and more wisdom than we who now join them, began our new War In America. From this moment the cry on our lips, the goal in our hearts, the drive behind our minds, our might, our very lives is LAND AND POWER, on this continent, in our time.

How we shall achieve this is the subject of this first Malcolmite epistle, written in October 1966, which we have called: War In America.

BROTHER IMARI Detroit, Michigan, U.S.A.

January 1968

PART I

THE NEW WARFARE

BACKGROUND OF VIOLENCE

THE black man’s struggle for freedom in America has always been violent. Taken prisoner in violent struggle in Africa, the black man used the violence of shipboard revolts, suicides, and self-mutilation to resist enslavement during the Middle Passage and, once in the New World, enlarged the pattern of revolt, suicide, and self-mutilation to include continuous and widespread sabotage. Throughout this struggle, whose earliest recorded moment occurred in South Carolina in 1526, and which lasted through the end of the Civil War in 1865, the slaveholder unfailingly met black struggle with a harsh and unfettered response.

It is true that from the end of the Civil War until the opening of black guerrilla warfare in New York City (Harlem) in the summer of 1964 — a period of 100 years — the black man in the United States conducted his struggle for freedom without resorting to violence as the institutionalized weapon he had made of it during the previous 300 years; but the struggle was, nonetheless, violent. It was violent precisely because the white man, unlike the black, never forsook violence as a primary instrument of control over the black man. While the black man’s response — sometimes, as in the summer of 1919 (During this summer, in major race riots in 20 cities, black men took a heavy toll of white attackers who, formerly, had met little retaliation, and laid waste to considerable white property), rising to a furious magnificence — was largely defensive and uncertain, the white man’s rape, assault, and murder of the black man continued without let-up throughout the most recent 100 years, as it continues today. And the fact that the white man in the North relies more upon the courts to carry out this violence, than upon the individual white citizen, as in the South, makes the fact of this violence of the white upon the black no less real and no less present.

Indeed, it is precisely the realization of this fact of white violence upon the black — the realization of the FACT, despite camouflage and denial — which brought brave, young black men into the streets of Harlem in 1964 and opened the present period of black warfare.

FIRST GOALS

AN important aspect of the black man’s resumed warfare is that it is being fought largely in the cities of the North. The DEACONS FOR DEFENSE AND JUSTICE, the courageous black armed force that sprang to life in the South, Mississippi and Louisiana, within a year after the first battle was fought in New York’s Harlem, has a leadership that is known and lives openly in the area of conflict: it began as a defensive organization and augurs to remain defensive so long as it is expedient for its leadership to remain exposed and vulnerable. Thus, the only aggressive use of black violence in the South during the first years of renewed black warfare occurred in Birmingham (this event was in 1963 and actually predates the Harlem warfare) and, on a smaller scale, in Atlanta in 1966. As in the North, both sites were large cities. But the big cities of the North have been pre-eminently the battlegrounds, the loci of greatest destruction being Harlem, Rochester, and Philadelphia (1964), Los Angeles (Watts) (1965), and Omaha, Chicago, and Cleveland (1966).

A second important aspect of the renewed black warfare is that it was initiated and carried out during the first three years (1964-1966) by young members of the most exploited class of black people. They were acting spontaneously, with no theoretical framework of knowledge beyond a basic understanding that they were being exploited by white people — deprived of education, jobs, decent housing, health, justice, and dignity — because they were black; with no objectives further than revenge, a free re-distribution of white-owned goods found in the black community, and relief — in any form, in any amount, however small — from the grinding deprivations of joblessness, ill-education, bad housing, and police brutality.

That units of the black underground army were present in Harlem (1964) and destroyed property with noteworthy effectiveness in Watts (1965) and Cleveland (1966) should not be overlooked. Nevertheless, the warfare was initiated not by the militant intellectuals and the organized underground but by the young black mass. Their objectives bear examination.

That a measure of revenge was achieved by the warfare of the black mass is certain. Revenge was taken against the white police who — while amassing a severely higher killedand- wounded toll against black men than black men amassed against them — were turned from swaggering brutes into furtive animals filled with fear and made to seek, in city after city, the help of National Guard (army) units. Revenge was taken, too, against the white economic exploiter. A dominating fact of black existence in the United States is that most of the property (especially where the black poor live) and virtually all of the business are owned by whites. The destruction and looting of these places afforded a measure of revenge and achieved, to a limited degree, another objective: the free re-distribution of goods — foodstuffs, appliances, furniture — belonging to whites and found in the black community.

The objective of meaningful relief from deprivation was more widely frustrated, however. Leaders of black civil rights groups, called upon by the white power structure to speak for the guerrillas, translated the drive for relief into a request for more recreational facilities. Joined by the black militants and the guerrillas themselves, the civil rights groups more correctly translated the drive for dignity into a demand for an end to police brutality. All correctly saw the demand for jobs, for income, as pure and unequitable.

That the demand for jobs was not met was demonstrated in October of 1966 by the issuance of a persistent statistic by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: nationally the unemployment of black people, in that time of national economic prosperity, continued to be more than double that of whites. White unemployment was 3.8 per cent; black unemployment, 7.8 per cent.

On a city-by-city basis the fact was that a few demonstration projects were initiated that amounted to a few more jobs for a painfully few black persons, and employers were verbally urged to stop discriminating. But largely, black people were told (as they had been told for years) to TRY HARDER: get education, dress and speak like middle-class whites. We were told, in short, that black unemployment was due to black people (i.e., our lack of education, lack of initiative), rather than to a design of the white man. Yet the contrary was the truth; statistics adduced by the City of Detroit’s own Commission On Community Relations in May 1963 ("Employment and Income”) were true nationally and to the point: black unemployment was not only twice white, but the median white HIGH SCHOOL graduate earned MORE than the median black COLLEGE graduate, a white with EIGHT YEARS of education MORE than a black with a HIGH SCHOOL (12 YEARS) DIPLOMA, and so on, in such a consistent pattern that the only explanation, this official commission concluded, was racial discrimination.

THE IMPACT OF WHITE RACISM

THE cause of black joblessness was, then, more than anything else, a psychological attitude on the part of whites. That attitude involves, first, a belief in white superiority and second, a commitment to white domination of the human race, the world, and all the world’s goods.

It is an attitude that exerts its presence first in the school systems; virtually every governmental unit in America, including the school boards, is dominated by white people, and their orientation has habitually and continually been WHITE-FIRST: they racially segregate the schools, either by law (this has been unlawful, theoretically, since 1954) or by extra-legal design and then proceed to develop and give superior facilities and programs to white schools, inferior facilities and programs to black schools. Whites, controlling purse-strings and the power of decision over black schools, not only guarantee thereby an inferior education to black children who stay in the schools, but drive large numbers of young black people OUT of the schools. Whites — and their black tools (those black teachers with white-oriented minds) — do this by continuous assaults on the black personality.

It is not so much the teaching of middle-class values — which blacks could learn — but the teaching of WHITE values, which blacks can only acquire at the cost of frustration and self-abasement. From the pictures in mathematics books, through the stories in literature books, to presentations in history texts, one standard of beauty is taught: White beauty. One essential ingredient for genius and courage is taught: the WHITE SKIN. These things the black cannot possibly attain (white beauty is not black beauty; white skin, not black skin). Therefore, functional sanity for the black man, in the normal course of things, cannot be achieved except by accepting black inferiority before white superiority, attaining those white attributes which are attainable — speech, dress, mannerisms, straight hair — and thereafter following the path of least resistance.

Yet the difficulty of attaining even those ATTAINABLE white standards of speech and manners, which confronts many members of the black mass, compounds for them the misery of the learning experience, alienates them from the majority of their fellows (who ARE attaining these values) and, especially, from the white world, and sends them out prematurely from school as “drop-outs.”

But the school system is only the beginning, not the explanation for a black unemployment rate twice as high as the white, for the phenomenon of whites consistently earning more than blacks with three and four years more education. The schools are only a primary place where the psychological orientation of the white man toward white supremacy and his commitment to white domination make their presence felt.

Rather, it is the white supremacist orientation and the commitment to white domination, operating in the minds of thousands of white personnel officers and employers all over the country that is responsible for the total exclusion of black workers (except as custodians) in thousands upon thousands of small and medium-sized plants all over the country. Where large companies are concerned, it is instructive that during six months of 1965 alone the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), moving reluctantly and superficially, filed 1,000 separate complaints of job discrimination against major employers and unions in the United States.

Once there was a great deal of truth in the assertion that the white man oppressed the black man because he needed cheap labor. By the era of the new black warfare (1964) this was no longer true. Highly mechanized, the American industrial society does not even need the black man as a domestic worker. Indeed, the black man was dispensable long before Harlem’s first shot. Black oppression continues today because the mechanisms for it are now built into the fabric of American life. Black oppression is simply the other side of the coin bearing the twin-headed monster of white belief in white supremacy and white commitment to white domination.

It is not simply what the schools teach. It is language, folk art, myths, religion. It is the representation of Christ, the Son of God, in a largely Christian land, as a white man. Courtesy alone, whatever the historical truth, would seem to dictate that in a land where one-tenth of the Christians are black, Christ — or at least SOME of the Biblical characters — would be represented as black SOME of the time. It is the endless glorification in screen and advertising of white beauty, white manners, and white conquest.

More than anything, however, the orientation toward white supremacy — with its corollary of black oppression — is supported and perpetuated by white insistence that white conquest of the world was achieved because white people were smarter and braver than those they conquered. White men will not teach and refuse to believe the simple truth that their conquest was achieved not only through the cultural accident of better arms at crucial moments (throughout history, barbarian peoples have often achieved this advantage over more civilized people), but because they were more ruthless than other peoples in the world. The whole history of white domination and black slavery, since the arrival of Vasco Da Gama off the shores of Kenya in the Fifteenth Century, has been the history of the white man’s savage disregard for simple justice and the equality of man.

THE FIRST HARVEST

THUS, the civil rights groups which spoke for the black guerrillas in the wake of the first three years of guerrilla warfare (1964-1966) diluted the gains which were to be won by the black man. The call for recreational facilities brought a pittance — a contemptuous response of the powerful to the powerless. Requests for fair play from the police could not be granted because white people, in control of the machinery of state, regard the police as their protection against black people — whom they know to have just grievances. Worse, civil rights groups, which joined the white power structure in emphasizing training as the solution to joblessness, were also joining the white power structure in promoting the lie that the black man’s lack of training was the cause of his unemployment. They were thus protecting for the white power structure the real and statistically demonstrable cause of the problem: the white man’s orientation toward white supremacy and his commitment to white domination.

They were, in other words, often unwittingly , preventing movement toward a real solution by moving off on a tangent. Black people are not only kept out of regular jobs by the bias of white hiring people, they are excluded from skilled trade apprentice programs purely by the bias of white skilled trade unionists. Neither situation could be remedied by the training of blacks.

The black militants who spoke for the guerrillas were generally more on target, for they emphasized “control.” They knew the invidious work of the schools and that the white man would not change what was going on in the schools, so they demanded control of black schools. They understood the function of the police, so they demanded partial control of them — review of their actions, increases in black policemen and black command. They demanded control of the federal government’s Poverty programs, supposedly designed to end black joblessness. Fundamentally they failed, even as the civil rights groups failed for other reasons, because they, the militants, had reached the core of what the struggle was about: CONTROL — whether white men or black would control the black man and his destiny. They failed because they, the militants, even supported by the guerrillas, had not arrayed the impression of enough power to make the white man relinquish that control.

PART II

STATE POWER AND

FURTHER WARFARE

THE NORTH AS A BATTLEGROUND

BLACK warfare against white control in the United

States will continue. It will continue not simply because the most exploited level of the black mass is alienated from the white majority or because numerous black militants of all strata have gained a true knowledge of white objectives and white psychology; it will continue because the white man is thoroughly committed to white domination and therefore will not allow the black man to depart peacefully from him, taking only that which in justice belongs to black people, nor will he permit the black man to live in association with him on a basis of real equality, as a power SHARER — unless he is forced to. Black warfare will continue for no other reason than that the white man will have it no other way.

But black warfare will move along new and predictable lines — because WE MUST WIN. First, thoughtful militants know that the Northern cities — where the warfare was fought for the first three years — are indefensible over the long-run. Although black populations in these areas run from 25 to 60 per cent, the cities are islands in the middle of white seas. In time of conflict, white strategy has been to surround black communities in the cities with police and National Guard (army) units, cutting these communities off from the outside. In a serious engagement food supplies within the surrounded areas could be depleted (as happened in Watts) in a week. The water and power supplies could in many instances be cut off, and the lack of sanitation services, including the blocking of sewers, could be used as a weapon against the entire black population of an inner city. Finally, the compactness of black-occupied inner cities in the North lends these cities, once surrounded, to classic and brutal military sweeps. Indeed, with the black man no longer an economic necessity in the United States — he is, in fact, for the white man, a decided inconvenience — the temptation to “solve the problem" by wholesale slaughter in black communities under siege may be too great for the average white leader to resist.

The defense against the white strategy of siege lies in black guerrillas OUT-SIDE of the ringed inner city wreaking havoc upon the factories, offices, police stations, and homes of whites in wide-ranging, random fashion; sabotaging and destroying their power and water and sanitation facilities, as attacks are made on our own. This will draw off forces holding the inner city under siege and serve to remind the white man that he has more to lose than the black man; it will serve, under favorable conditions to inspire the white man to break off military engagement altogether. But this strategy is not sufficient for long-run-decisive success.

The inner cities of the North have other deficiencies. Black functionaries who serve white interests have for more than 30 years been appointed and elected from black areas to posts of political importance in Northern cities. There are scores of black judges, councilmen, and state representatives, but for the most part these people serve white interests first and black interests only incidentally, if at ail. White control of these people and the entire political machinery of the cities is achieved through organization and huge amounts of campaign money. When black officials oppose the white machines in the interests of black people, they are destroyed by the machines — directly, as was Chicago Alderman Benjamin Lewis, assassinated in his office in gangland style, or as was New York Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, who in 1966 was effectively stripped of the vast power which he, as a Committee chairman, had wielded in behalf of black people’s struggle. (In a counterpart action in the big-city South in 1966, Julian Bond of Atlanta, a member of the militant and involved Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, SNICK, duly elected to the Georgia House of Representatives, was denied his seat by other Georgia House members TWICE — first after the regular election and again after he won re-election in a special election to fill his vacated seat.)

In head-to-head confrontation the white man in the North has control of the voting machines, which are subject to tampering before being installed for an election. In the spring of 1964 an all-black political party, the Freedom Now Party, won a place on the Michigan ballot and waged an exciting, intensive campaign for election of a full slate of candidates in the November contest. When a running tally of ballots for the Party’s gubernatorial candidate was given on election night, he had well over 20,000 votes; but when the final official tally was given, that vote was reduced to just over 4,000 (black militant organizations had more than 4,000 vote-age members in the Detroit area alone)! But militants drew a lesson from that election: if black people don’t control the state-wide election machinery, there is no guarantee that votes will be counted. And in the North, where black populations county and state-wide are considerably less, proportionately, than they are in the cities, there is virtually no chance in the normal course of things of gaining control of the election machinery.

Ultimately whites in the North have prepared another procedure to keep real political power out of the hands of blacks, preparing against the day when black numbers and black sentiment in the cities make it impossible for whites to control the candidates and dangerous to rig the voting machines. That procedure is called COUNTY HOME-RULE: it is the act of moving the REAL POWER of government — taxing, police, planning — from the city-level, where blacks would dominate, to the county-level, where whites dominate.

Thus, the Northern cities, because of large concentrations of black people, are suitable for possible spectacular holding actions: astute political activity could elect black judges, councilmen and representatives who are black oriented and able to afford certain limited protection to the black struggle and those active in it; and the Northern cities can also provide foci from which to inflict severe guerrilla damage upon the white man’s property and industry, to make him (possibly) stop and think. But the Northern cities are militarily indefensible over the long-run and completely unamenable to black political control.

THE SOUTH AS A BATTLEGROUND

THE South, however, is another matter. For in the

Deep South — Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina — there are many counties populated with over-whelming black majorities. Indeed, the 1960 U. S. census showed black people in Mississippi as being 42% of the population; in Louisiana, 32% of the population; in Alabama, 30%; in Georgia, 29%, and in South Carolina, 35%. Given the patterns of concealment routinely practiced by blacks against the power structure, the actual figures are apt to be 10% or more higher. In the South numbers are our strength. In the South, too, black people are not concentrated in vulnerable islands as we are in the North; with the land all around us and the farms to support us, in the South our military prospects brighten like gold.

The political prospects, because of our numbers, are equally auspicious. Here, in the Deep South, black people may run through to its natural conclusion our political destiny in this country. Our numbers give us the basis for state control in Mississippi, the possibility of state control in Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina, provided that conditions could be created to induce less than one-fourth of the 12 million black people now living outside of these states to immigrate to them. (Author’s Note: This is another story, but such immigration is not unparalleled in history. Note the Jewish settlement of Israel; the British settlement of Australia, Rhodesia, South Africa, the New World; the American settlement of the West, and the Mormon settlement of Utah.)

STATE POWER

THE importance of state control becomes crystal clear when seen against the objectives and failures of the valiant black guerrillas in the North’s big cities from 1964 through 1966. Every goal sought by them could have been achieved — instead of frustrated — had they, instead of the whites, been in control of state power. Transplanted to Mississippi, the course of events would be obvious. To control state power is to control the state police and (to that degree that black state power could stand against white federal power) to control the state National Guard. Under control of emancipated blacks the state police could be purged of racists by simple legal procedures involving indefinite suspension of all policemen accused of racist activity, pending trial board action. This would mean indefinite suspension of virtually every white man on the force, and while they litigated their suspensions in the courts (mostly in the state courts of emancipated black justices) their jobs would be filled by emancipated blacks. State power could thus end police brutality against blacks; indeed, it would convert the police into a force supporting black people.

Obviously, too, state power under emancipated blacks would be used to purify the school system and bring to black children the best possible education.

State power could be used to end unemployment. Since statistics positively show that black unemployment and under-employment are largely caused by racial discrimination, state power, in the hands of emancipated black men, could be used to open the doors of plants to black workers — or seize them entirely as penalties for persistent discrimination. No trade union would be allowed to operate in the state unless it admitted black apprentices and made a floodgate effort to make up for the exclusions of the past.

More than this, state power in the hands of emancipated blacks would be used to make jobs. Black people in the United States have existed as a colony within a nation. We have been exploited for our building skills and our labor — our raw materials — and we own not a half-dozen manufacturing facilities worthy of the name, no sea or air shipping companies, and scarcely 15 banks. Even the farms, for the most part, are not ours. State power would be used as it is used in every other colony that achieves its freedom: to launch industries OWNED BY THE PEOPLE, to benefit the people. Not only would power (electricity, gas, atomic energy) and communications come under state direction, but the state would go directly into agriculture and industry, assisting private owners, on the one hand, as banks should do, and directly opening manufacturing plants, shipping lines, and other needed, job-making, prosperity-creating concerns, on the other hand.

In short, state power could and would be used by emancipated blacks to create A NEW SOCIETY, based on brotherhood and justice, free of organized crime, free of exploitation of man by man, and functioning in a way to make possible for everyone the realization of his finest potentialities. (What must be made clear in this chapter is that black people, running a “state” which remains within the United States federal union, could, under the best conditions, end police brutality as outlined in the first paragraph of this chapter. Black state power of this sort could also, conceivably, purify the educational system. But both these objectives run counter to what the “American” system stands for, and would therefore tend to meet the same kind of federal opposition which makes the accomplishment of the goals of the last paragraphs (i.e., ending employment discrimination and making full employment) impossible through the use of state power within the United States federal union. The state power referred to here is the power of a free and independent separate state. Part III, following, explains why.)

MISSISSIPPI

BECAUSE of powers reserved to the individual states under the United States federal constitution, the state level of government is the ideal level (as opposed to the city or county level) at which black power could be brought to bear in creation of THE NEW SOCIETY. Even with the rapid and extensive growth of federal power and control since 1932, the state still retains tremendous regulatory and initiatory powers over life within its borders. Police and national guard, taxing and banking, election machinery and courts, licensing of many sorts all remain under broad state jurisdiction. And Mississippi, primarily because of its great black population and its seaports (on the Gulf of Mexico), seems the most favorable state in which Black People might reach toward the logical conclusion of our destiny in this land, might attempt to build THE NEW SOCIETY under black control. (The founding of the Republic of New Africa has made it unnecessary for revolutionaries to seek control of the state within the U.S. federal union. Our work is the direct work of winning consent of the people to the jurisdiction of the Republic of New Africa and away from the United States.)

If black people are successful in Mississippi, a systematic attempt would be made to bring three million similarly minded black people from the North into Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina, so that these states might also be brought under black control and into a five-state union with Mississippi, with ports on both the Atlantic and the Gulf — a smaller union than the old 11-state Confederacy, to be sure, but with infinitely greater prospects for success. But THE ROAD TO BLACK CONTROL in Mississippi is perilous and by no means accomplished by our mere wishing it.

For if the state of Mississippi in 1966 contained the most valuable asset for black control (a near-majority of black people), it also contained all the obstacles to black control found in the other states — and one more: open and ubiquitous white violence.

The move to subvert black power in Mississippi and deliver black candidates into the hands of white control once blacks achieve the vote in that state was well underway by 1966. It was being engineered by the United Auto Workers (UAW) industrial union and carried out by small cadres of black and white unionists, some from within the state, some from without, who were wooing black vote registration workers with money to underwrite a state-wide registration campaign — a campaign which the very black organizations being wooed (the Elks and Masons, teacher societies, professional associations, voters leagues, fraternities, sororities) could, with sacrifice, themselves underwrite. Anxious for any sign of good faith and decency on the part of whites, anxious not to subvert any genuine effort at inter-racial cooperation in a state where a lack of inter-racial cooperation constantly bedevils life, black leaders in 1966 seemed inclined to accept the UAW aid. They were acting without a knowledge of the way the UAW for over 20 years has treacherously used its money and organization to subvert black interests in Detroit.

For, if the Mafia corrupts and despoils black effort in Chicago; if Tammany Hall (the Democratic Party) makes a mockery of black people in New York, and if machine politics and a slave mentality in black officials in Cleveland undermine black power there, in Detroit it is the United Auto Workers (AFL-CIO), under its president Walter Reuther, that has been the constant enemy of black unity and black progress. In 1966, at a moment when it appeared that black people in Detroit might elect several judges to the 13- member city court — where prior to 1966 only one white-thinking black jurist sat and where black people have constantly been victimized in an open judicial travesty the UAW refused to support the one non-incumbent black candidate, George Crockett, with the best chance of election. Indeed, UAW workers within the Democratic Party successfully used their power to deprive Crockett of the important endorsement of the First Congressional District Democratic Party organization (a predominantly black district which sent John Conyers to Congress). The result was calculated to be disastrous for black Detroiters — even though Crockett is not a “black-thinking” lawyer he is, by other lawyers’ estimation, one of the fine legal minds of the state, and he is socially conscious. The UAW action was calculated to return the city court safely to white hands for as many as 12 years to come.

In 1965, when a general cry arose from the Detroit black community to elect three black persons to the all-white nine-member city council, the UAW spurned support of such a campaign, instead threw its aid to an obscure black party functionary, a gifted but innocuous black minister, and a number of whites of limited talents, while talented black candidates with programs for progress (Jackie Vaughn, Reverend Albert Cleage) were spurned. In 1964 UAW functionaries and allies fought the Michigan Freedom Now Party, and the UAW gave its support — as it had in years past — to the worst white racist, Samuel Olsen, ever to occupy the Wayne County (Detroit) prosecutor’s office. In 1962 the UAW opposed the drive to elect three black men to Congress (that was the last year when it would be possible in Detroit for years to come). The record is nearly endless — and CONSISTENT in the UAW’s dedication to white control and the subversion of independent black candidates.

Worst, in its own area of organized labor, the UAW has failed to wage any meaningful campaign to force skilled trade unions to accept black apprentices in number. The UAW is a wolf in lamb’s clothing, and it has descended upon black people in Mississippi as upon peaceful sheep.

(Curiously, one of the black salaried UAW functionaries periodically at work in Mississippi, Horace Sheffield, has himself been the victim of Walter Reuther’s arbitrariness and disdain for black people. In disfavor with Reuther over internal matters, including Reuther’s favoring of another white-thinking black functionary, UAW national vice president Nelson Jack Edwards, Sheffield was ordered by Reuther in early 1966 to move to Washington. This would have removed Sheffield from the prominence he had gained in Detroit as a newspaper columnist and a leader of the civil rights-oriented Trade Union Leadership Council (TULC). It would have cleared a height in the black community for Edwards, who had founded an organization similar to TULC and become a columnist in the same UAW-dominated newspaper, the Michigan Chronicle, a black-owned weekly, which had given Sheffield his first column space. Reuther finally relented on the demand that Sheffield move to Washington — ONLY after black civil rights groups in Detroit had created a storm over removal of a black LEADER but not before reminding Detroit blacks that Sheffield worked for him, Reuther, not them. Thereafter, Mr. Sheffield was assigned to spend most of his time on the road — including Mississippi.)

THE ANTI-BLACK BLACKS

CONCERTED efforts of white organizations like the UAW to dominate the black vote in Mississippi are not the only obstacles to black control. There is what has become known as the “TUSKEGEE SYNDROME.” This refers to the state of the black mind in Tuskegee, Alabama, where, in 1965, a black voting majority, after a campaign by leading black people in the community against black government, voted a white majority into office.

The sources of this syndrome are not hard to identify. Raised on a saturation diet of white supremacy, believing that God himself and his son too are white, great numbers of black people in America have a secret, abiding love of the white man that flows from deep recesses of the subconscious mind. It is matched by a complementary subconscious hate of black people, of self, and manifests itself in a pervasive doubt of black ability to succeed at anything. These ingrained attitudes in black people have been played upon — to the detriment of every movement for black unity and black self-help in our history — by white-dominated organizations like the NAACP, which for 50 years has held the spotlight in the fight for freedom. These organizations teach, as gospel, that racial INTEGRATION is the only solution to our problems (they preach this to black people, not to white) and that “all-black” organizations in the fight for freedom are “segregation” and this “segregation,” like the other segregation, is bad. (ALL-BLACK churches and undertakers and barrooms are alright.) This teaching squares easily with the black man’s sub-conscious self-doubt: many black people are easily convinced, therefore, that “anything all-black is all wrong.”

They are especially convinced and led astray in this regard because the actions of MOST — thank God, NOT ALL — leaders of black communities are designed to lead them astray. Great numbers of black teachers and professors, great numbers of college-educated black people who fill leadership positions (often because they are designated by whites) in black communities believe in their own inferiority but believe even more in the inferiority of their less well situated brothers. It is they, together with the minority of cynical, bought blacks, who are the passkey to the first and greatest barrier — black disunity — to black control in any community. Because of these people, black unity in the past has been impossible; without these people, black people would have nothing to fear from attempts of outsiders, like the UAW, to control black candidates and black politics. We would have considerably less to fear than we now do from economic or even physical attacks from whites.

While these black leaders almost always profit from their subservience to whites, and some perform for whites for no reason other than profit, most are motivated by a conviction that there is no other course. For all this, these people are no less dangerous and obstructive to the acquisition of black power in Mississippi (or elsewhere) than were they motivated purely by profit. Those motivated by profit have from the very beginning forfeited their right to existence; those motivated by conviction are due a brief solicitation, but, after that, their further existence, unreconstructed, cannot be justified.

It is a question of halting, in good time, IN OUR TIME, the coercive rapes which our sisters suffer routinely at the hands of white swine; it is a question of preventing the extinguishing of light in the eyes of bright young black children, still too young to know; of ending the blind squandering of genius, and beloved mediocrity; of banishing all manner of injustice which our people hourly suffer, the continued crushing of self-respect, the stifling of ambition and hope; of ending exploitation; of bringing, with all speed, a new and better life, a new and brighter world, a NEW SOCIETY.

VIOLENCE

IF we cannot tolerate those within our ranks who work against black unity, we must resolutely destroy whites who attempt to inflict violence upon us. Those who labor for the New Society must harbor no secret doubts about the white man’s dedication to white domination; failure to understand the magnitude and completion of this dedication could be more fatal to our movement than many armies. History must be instructive to us. Stanley and Rhodes in Africa are classic examples of white men who ingratiated themselves with blacks, exchanged solemn commitments of friendship and consummated treaties — not so that men of different cultures might learn from one another, trade with one another, and live in peace, but only to use this ingratiation, these exchanges of friendship commitments and treaties to deliver blacks to white domination. White men are without honor in power encounters with people of color; they have no scruples that prevent the use of any method, the stooping to any perfidy to gain or maintain white domination.

In the United States itself the history of the white man’s dealings with the Indian in white conquest of the West parallels the treachery of Stanley and Rhodes in Africa: no treaty that was not a convenience broken at white will, no friendship that was not turned to service of white domination.

The character of the white-run war against Japan exemplified the attitude of unbridled savagery which the white American indulges toward people of color: the wide-spread use of flame-throwers and fire-bombs in the Pacific, contrasted with their limited use in Europe; the use of the atomic bomb. Yet little parallels the 100 years of white lynching of blacks in America — the open and systematic murder of defenseless thousands in the years just after the Civil War and just after Reconstruction; the burning-alive and mutilation of children, as well as hapless adults; the sudden unanswered disappearances in the back-country; the use of the courts, the electric chair, the policeman’s gun and club to take away the liberty, the limbs, the faculties, and the lives of hundreds of thousands of black people. Hardly anything parallels this; but the conduct of the white man (who in 1966 was using 100 thousand unthinking black troops along with the white) in pursuing the war in Viet Nam is a concentrated exercise in kind. Here, again, is the wanton destruction of people’s homes; the burning to death, by napalm (flaming jelly) and flame-throwers, of hundreds upon hundreds of Vietnamese women and children huddled in holes — on the excuse that guerrillas might be huddled there with them; the maiming of countless more; the saturation bombing of huge tracts of populated country simply because it is held by “the enemy.” (Black people MUST disassociate ourselves from this criminal and barbarous American effort.)

If we learn nothing from Africa, nothing from the racist conduct of the war against Japan, and nothing from the war in Viet Nam, our own 100 years of lynching in this country, concurrent as it was with the white man’s treacherous and systematic extermination of the Indian, must teach us that whites who attack us must be pursued to their sources and destroyed completely at their sources. This must be so, whether the racist criminal wears a policeman’s uniform or not.

We must remember that at the end of Reconstruction, when racist whites had no state power in their hands, they drove black people from the government and from the electorate using a night-riding, civilian vigilante force. With state power in their hands, they have continued for more than 80 years to cultivate the white civilian capacity for violence. In Mississippi, where the black drive for power must proceed in county-wide campaigns as a prelude to total control of the state, black workers face, as they have in the past, violence emanating from white racists operating illegally under cover of state power (the police) as well as violence from white vigilante-type organizations and white individuals acting illegally on their own. All three must be utterly destroyed, county-by-county, using the black underground army first and, then, the county sheriff’s organizations as the counties come under our control. Anything short of this is to make a mockery of claims of black control, is to leave for future flowering the seeds of resurgent white violence, a fundamental deterrent to the New Society.

GOD, MEN AND VIOLENCE

WHEN black men are called upon to fight in the United States Army and are sent, as they are in Viet Nam, to take the lives of foreign patriots who bear them no ill will, no cry is raised that black men should practice non-violence and refuse to go. But when black men are urged to arms to protect themselves in the race struggle in the United States, the cry of non-violence for blacks fills all the land. It will fill it again now. It does not matter. What matters is what black men themselves think. Those of us in the struggle who are atheists and agnostics, those who are animists and those who follow Islam are unfettered by the chains which a perjured teaching has placed upon those of us who are Christian.

More than any man in recent years Martin Luther King is responsible for this criminal crippling of the black man in his struggle. King took an incredibly beautiful, a matchlessly challenging doctrine — redemption through love and self-sacrifice — and corrupted it through his own disbelief. Martin Luther King’s non-violence is a shallow deceit: on no less than three occasions between 1961 and 1965 King called for or condoned (as when Watts occurred) the use of troops. But he urges black people to non-violence. If he did this because he did not think we could win violently, and said so, that would be one thing; but he tells black people to be nonviolent because violence is wrong and unjustifiable. And yet he calls for armies, WHITE-RUN armies. . .

Black Christians must remember that while Christ taught peace, forgiveness, and forbearance, his disciple Peter carried a sword and used it in Christ’s defense at Gethsemane, Christ himself spoke of legions of angels who would fight for him, and Christ himself turned to violence to drive the money-changers from the temple.

There are Christian black men in the struggle, seeking to serve God and loving mankind, who like Christ with the money-changers, have seen the uselessness of further forbearance and have therefore committed themselves to unrelenting violence against violent whites. They are men who hate violence and seek a day when men will practice war no more, but who know that at this juncture in history we are left no other course. If the white man were to be redeemed and reconciled to us by our love, he would have been reconciled before the one hundredth year, because we have loved him mightily. If the white man were to be saved by our suffering, the last ten years from Montgomery through Magnolia County and Birmingham to Chicago — the sacrifice of the actual lives and sight and health and chastity of our dearest black children, many, like those in the Birmingham bombing, not yet teenagers — this non-violent, loving, unstinting sacrifice should have saved him. The fact is that our continued non-violence will NOT change the white man and would lead US only to extermination.

God is with us, to be sure. But the natural miracle is a rare and thoroughly intractable phenomenon; for the most part, the miracles of God are worked through the brains and arms of men. God will deliver us, but CANNOT unless we act. And if we act, with resolve, we can hack out in this American jungle of racism, exploitation and the acceptance of organized crime, one place in this hemisphere where men of good will may build the GOOD NEW SOCIETY and work for the reconstruction of the whole human world.

PART III

THE NEW SOCIETY

FEDERAL OPPOSITION

NEXT to black disunity, and a greater threat even than the presence of white violence is the power which the federal government can and almost certainly will bring to bear against black efforts to transform Mississippi into a model state. An impressive array of law and court decisions exists to interfere with the use of state power to end unemployment through state-run industry. The federal court system with its enforcement arm of U.S. Marshals, rarely used to benefit black people, represents a hostile force within the borders of the state to enforce anti-black court decrees; the state National Guard, taken from state control by nationalization, would stand with the regular U.S. military establishment and the marshals as an instrument for frustrating black state power under the guise of enforcing anti-black federal court decrees. Beyond this, the federal presence, ready to be expanded like the tentacles of an octopus, pervades agriculture, vocational training, employment planning, health, transportation, labor relations — in short, a host of central state activities where arbitrary federal actions could seriously impair, if not destroy, programs instituted by enlightened black state power.

That federal power would be used to destroy black power is certain not simply because of the explicit statements against black power made in 1966 by such leaders as Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy, or alone because the deep commitment of white Americans to white domination is so demonstrable. It is certain because federal power has been used in the recent past specifically to destroy black power.

A flagrant example is the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This party organized to work within the national Democratic Party and in 1964 achieved an overwhelming consensus of support of blacks in Mississippi who would have been eligible to vote had they not been prevented because they were black. The MFDP went to the Democratic Party's national presidential convention in Atlantic City in the summer of 1964 and asked to be seated instead of the Eastland faction as the official Democratic delegation from Mississippi. Despite the MFDP’s presentation of evidence that the Eastland faction was systematically depriving black people of the vote and despite the MFDP’s showing that the Eastland faction had not supported the national Democratic Party’s candidates in Mississippi and the MFDP’s assurances that the MFDP did and would support the national party in Mississippi, the national party refused to take accreditation away from the all-white Eastland faction and give it to the inter-racial MFDP. This was the party of Lyndon Baines Johnson and all the Kennedy-Johnson white liberals, and Lyndon Johnson was President.

Again in January 1965 three women MFDP Congressional candidates — Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, Mrs. Annie Devine and Mrs. Victoria Gray — who had won election in a special election held under great difficulty largely in churches in 56 of Mississippi’s 82 counties, presented themselves at the convening Congress and asked to be seated instead of the regular, illegally elected (95 per cent of Mississippi’s eligible black voters were not allowed to vote), all-white five-man delegation. Once more they were denied: once more, despite an explicit constitutional provision which gives the Congress the right to choose between such challenging parties; once more, despite the ability of Lyndon Johnson at that time to muster overwhelming majorities in the Congress on virtually any subject. To be sure, the seating of Mrs. Hamer, Devine, and Gray would have accomplished a power revolution in the state of Mississippi: it would have broken the exclusive power of Eastland, dividing that power with the MFDP’s chairman Aaron Henry. Yet it would have been a revolution WITHIN the Democratic Party, subject to national party jurisdiction and discipline. But federal power was used to prevent even this reasoned and generous compromise.

Politically this action was of a piece with the later use of federal power (in 1966) to strip Congressman Powell of the power he was using to benefit blacks, and the reluctant performance of the federal courts in keeping from Representative Julian Bond the seat he had legally won in the Georgia House of Representatives.

Further, no state governor has ever been arrested and charged by federal authorities with violating his oath to uphold the U.S. constitution, although several Southern governors — notable among them: Barnett, Coleman, Faubus, Wallace — have not only publicly declared their intention not to uphold federal law but have systematically violated federal law in matters of schooling, voting, and the protection of civil rights. When bodies of three unidentified black men were dredged up in Mississippi rivers during the search for three slain civil rights workers in 1964, federal power was not used to find the murderers of these innocents, though it was clear the state would not attempt to do so; nor has federal power been used to prevent or solve the countless murders committed against nondescript blacks in Mississippi (or elsewhere) before and since then. This failure to use federal power is in fact a studied use of federal power to uphold white domination.

And what is true of politics and murder has been true of employment and housing. Federal power has never been used to impose penalties upon industry to end discrimination — and discrimination accounts for more than half of black unemployment. In housing black people have since 1961 pleaded in vain for relief from the heartless ravages and hardships worked upon us by federally sponsored urban renewal; blacks in Harlem, forced into one of the greatest concentrations of housing unfit for human habitation in the world, during the same period (1961-1966) conducted rent strikes designed to force the owners of this housing to improve it but received only indifference and hostility from the federal government.

Interestingly, the single most powerful man in housing in the federal government during this period was a black man, Robert Weaver; while the second most powerful man in the federal anti-job discrimination machinery was also a black man, Hobart Taylor. Their failure to take these actions in industry and housing which would be simple, natural recourse to a black power government in Mississippi may indeed reflect their lack of courage and lack of identification with the black mass, but more than this it reflects a disarming white liberal disposition in America that came into vogue with John Kennedy: the tendency to select blacks for high government posts so long as these blacks support white domination, serve white interests, and take no initiatives in behalf of the black mass. It reflects, finally, a rock-firm opposition to black freedom, a clear and determined use of federal power to maintain white domination of the black man in the United States.

Because the presence of federal power within a state is so pervasive (i.e., through the federal courts, federal agricultural agents, federal participation in employment planning and labor relations, schooling, health, transportation, etc.) the federal government has a capacity for destroying black state power which is far beyond the capacity of whites within any given state. Worse: it not only has the capacity, it has the WILL to use that capacity. But this capacity and will are not without a potent counter.

THE ANSWER TO FEDERAL OPPOSITION

THE answer to federal opposition to black state power is a complex of studied moves POLITICAL, DIPLOMATIC, ECONOMIC, AND MILITARY.

The crucial first step is the early acceptance of an essential and inevitable decision by those who seek black state power. This is the decision to withdraw the state (ultimately, withdraw the entire, new, five-state union of Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina) from the United States and establish a separate nation.

This is necessary because the inevitable opposition of the federal government would be irresistible so long as it operates within the state; it must be put OUTSIDE the state.

Of first importance are the diplomatic moves. As Malcolm X taught, the black man’s struggle must be INTERNATIONALIZED, for it is only within the United States that we are a minority. Joined with other peoples of color beyond the American borders, black men bestow upon white men the status of a minority. The struggle must be internationalized for an even more basic and directly negotiable reason: we must draw to our cause the moral and material support of people of good will throughout the world; this support, correctly used, could impose upon the United States federal government an amount of caution sufficient, when coupled with the military viability of the black state itself, to protect that state from destruction beneath certain and overwhelming federal power.

In short, the effort to win public support for the black struggle from the Afro-Asian nations, started in earnest by Malcolm X and maintained so resolutely by Robert Williams, MUST BE CONTINUED AND INTENSIFIED; we must, moreover, continue and intensify the effort to raise serious, substantial questions concerning the status of black people in the United States and bring these questions before the United Nations and the World Court. Fortunately, the groundwork for this effort has already (by 1966) been faithfully laid by such men as Robert A. Brock, founder of Los Angeles’ SELF-DETERMINATION COMMITTEE, and Baba Oserjeman Adefumi, founder of the New York-headquartered YORUBA COMMUNITY.

As Adefumi, Brock, and their fellow workers have shown, the central questions to be brought before the United Nations and the World Court are two:

A. THE RIGHT OF BLACK PEOPLE AS FREE MEN TO CHOOSE WHETHER OR NOT THEY WISH TO BE CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES. This right was never exercised: freed from slavery by constitutional provision, black people were given no choice as to whether they wished to be citizens, go back to Africa or to some other country, or set up an independent nation. Instead, the OBLIGATIONS of citizenship were automatically conferred upon us by the white majority, while the RIGHTS of citizenship for black people were made conditional rather than absolute, circumscribed by a constitutional provision that “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation," and subjected to 90 years of interpretation and re-interpretation by the courts, the Congress, and the state legislatures. Adjudication of this question must bestow upon those black people wishing it a guarantee of their right to be free of the jurisdiction of the United States and assure that their right to freedom shall not have been jeopardized by the payment of taxes, participation in the election process, or service in the military during the period before adjudication. These later acts are participated in by the blacks in America who seek adjudication, only under coercion and as defensive measures.

B. THE RIGHT OF BLACK PEOPLE TO REPARATIONS FOR THE INJURIES AND WRONGS DONE US AND OUR ANCESTORS BY REASON OF UNITED STATES LAW. Reparations have never been paid to black people for the admitted wrongs of slavery (or since slavery) inflicted upon our ancestors with the sanction of the United States Constitution — which regulated the slave trade and provided for the counting of slaves — and the laws of several states. The principle of reparations for national wrongs, as for personal wrongs, is well established in international law. The West German government, for instance, has paid 850 million dollars in equipment and credits, in reparations to Israel for wrongs committed by the Nazis against the Jews of Europe. Demands for reparations, funneled through a united black power Congress, must include not only the demand for money and goods such as machinery, factories and laboratories, but a demand for land. And the land we want is the land where we are: MISSISSIPPI, LOUISIANA, ALABAMA, GEORGIA, and SOUTH CAROLINA.

The bringing of the first question to the United Nations — the question of black people’s right to self-determination — creates a substantial question demanding action by that world body and puts the black power struggle in America into the world spotlight where the actions of the United States against us are open to examination and censure by our friends throughout the world. It provides these friends, moreover, with a legal basis for their expressions of support and their work in our behalf.

The raising of the demand for land, as part of the reparations settlement, infuses needed logic and direction into the American black struggle and increases the inherent justice of our drive for black state power and the separation of the new five-state union from the United States.

The separation is necessary because history assures us that the whites of America would not allow a state controlled by progressive black people, opposed to the exploitation and racism and organized crime of the whole, to exist as a part of the whole. Separation is necessary because black people must separate ourselves from the guilt we have borne as partners, HOWEVER RELUCTANT, to the white man in his oppression and crimes against the rest of humanity. Separation is possible because, first, it is militarily possible.

When the 13 American colonies declared their independence from Britain, they also forged an alliance with France, which not insignificantly contributed to the colonies’ victory. When the Confederacy separated from the United States, it formed alliances with Britain and other European powers, and these alliances might have sustained her independence had not this creature been so severely weakened by sabotage and revolts of the slaves themselves and their service in the Union Army. In more recent times the state of Israel was created in 1948 and maintained against Arab arms by her alliances with the United States and Britain. In 1956 the independence of Egypt was maintained against invasion by Israel, supported by France and Britain, by her alliance with Russia: Russia threatened to drop atomic missiles on London if the invaders did not withdraw. In 1959-1960 an independent, anti-capitalist Cuba was saved from invasion and subjugation by American might (as American might would invade and subjugate another small Caribbean island republic, the Dominican Republic, in 1965) because, again, of an alliance with Russia.

The lesson is clear: black power advocates must assiduously cultivate the support of the Afro-Asian world. MORE, that moment when state power comes into our hands is the same moment when formal, international alliances must be announced. Indeed, these alliances may prove our only guarantee of continued existence.

CHINA

IN 1966, as he had in 1963, the leader of the CHINESE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC, MAO TSE TUNG, pledged support of the Afro-American’s struggle in America. Because China was in 1966 the only Afro-Asian nuclear power, and because China augured soon to have delivery systems — missiles and submarines — capable of striking anywhere in the world, China becomes able to exercise upon the United States the same kind of nuclear deterrence which the United States and Russia exercise upon one another, and which Russia exercised upon Britain in 1956 to save the independence of Egypt. ALLIANCE WITH CHINA IS, THEREFORE, OF UTMOST IMPORTANCE. The presence of Chinese nuclear subs in the Gulf of Mexico, supporting black people in Mississippi who have well made their case for independence and land before the United Nations, may tend to discourage the overt and reckless use of federal arms to wreck black power.

Yet alliance with China may prove more difficult, psychologically, for black people than logic might suggest. Subjected to the rampant racism that all Americans must daily live and breathe, many black Americans have not only absorbed an abhorrence for " communism” (which, almost like racism, is also constantly taught) but have absorbed the fear-hate reaction toward the Chinese which white people possess. Black people must remember, where communism is concerned, that white Americans have no fear of white communists that prevents them from giving aid to Yugoslavia, trading with Poland, Hungary, Rumania, and Czechoslovakia, and seeking the broadest types of commercial and cultural relations with the Soviet Union. If white Americans do not fear WHITE communists, why should Americans of color fear communists of color?

The answer, of course, is race prejudice. But black people should remember that 300 years before Vasco Da Gama, a white man, sailed around the horn of Africa and rained death, mutilation and destruction upon the prosperous cities of the black Swahili, the Chinese had been trading IN PEACE AND FRIENDSHIP with these same blacks. The Zeng (the blacks) and the Chinese exchanged ambassadors. Indeed, the whole history of contact between yellow and black stands in marked and beautiful contrast to the history of contact between white and black. This tradition of peace and friendship with the Chinese, of mutual respect, is the tradition upon which black power advocates build.

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL VIABILITY

IF international military alliances can preserve us, the creation of new political and economic arrangements can strengthen us.