My son, we have now come to that pivotal moment where we begin to recount the actual events in the history of our family in America. The telling of the story begins with your great, great grand Uncle Eustace Blake, who, on August 9, 1974, stated,

"Our forefathers were George, Jack, Yancey. Yancey Blake married Melissa Page. Yancey begat nine children by Melissa. Two boys and seven girls. Boys: Yancey Jr and John Addison (grandfather of Eustace). During the civil war a group of Federal Soldiers came past the house of my grandfather (Yancey Blake), Yancey Blake Jr. joined them and was never heard from anymore.”

Picture of a young boy photographed by Brassa Mada (Siphiwe Baleka, the great, great, great, great, great grandson of Brassa Nchabra) during his return visit to his homeland in January, 2020.

Brassa Nchabra

Around 1758, Brassa Nchabra was born in the village of Unche, in Nhacra, the homeland of the Binham Brassa people who, today, are called “Balanta”. He lived in what is called the three rivers or southern rivers area that encompasses the territory south of the Casamance River to the Cacheu River and Bissau on the West African coast of the modern-day country of Guinea Bissau.

Portuguese map of the Balanta homeland, 1844

Brassa Nchabra’s family was free. They paid no tribute or taxes to any chief or king. They recognized no state structure or authority having any coercive power over them. There was no law restricting them in any way except for Natural Law which had the following three requirements:

Balanta must not injure or kill anyone;

Balanta must not steal or damage things owned by someone else;

Balanta must be honest in interactions and must not swindle anyone.

At the time, the Balanta people raised cattle and dominated the local markets because they were the best farmers in the area. They lived a life of freedom and economic dominance.

Brassa Nchabra’s community was at war with the Christians from Portugal and England who invaded their homeland and who employed Bijago, Fula and Mandinka manhunters to ambush Balanta women and children heading to the markets. During the 1760’s, Brassa Nchabra was captured, most likely in such an ambush, and sold to English slave traders. Since all slave trading in the area was done under the authority of the Portuguese Crown who gave a monopoly of the trade to a single company called Companhia General do Grao Para e Maranhao, the English slave traders were considered as illegal pirates violating European law.

Now imagine the terror and trauma of the young boy Brassa Nchabra, no more than 8 or 12 years old, being kidnapped from his family and put in chains while witnessing the brutalization, violence and rape of the other captured victims. . . .

Building at the Fortress of Cacheu, built in 1588, were slaves were imprisoned.

Inside slave holding pen at Fortress of Cacheu.

Shackles used at Fortress of Cacheu.

Pit where the rebellious Balanta were held.

The Sally's Ship account book offers a meticulous record of a slave ship’s voyage in 1764, describing the date of each purchase of an enslaved African and precisely what was traded for him or her. Unfortunately, it offers little information about his ship's exact whereabouts. It is unclear where the Sally first made landfall when it arrived in Africa on November 10, 1764, but by December it was at James Fort, the primary British "factory," or slave trading post, on the Upper Guinea coast, near the mouth of the Gambia River. The ship seems then to have proceeded south along the coast of what is today Guinea-Bissau, stopping briefly at the city of Bissau before anchoring somewhere near the mouth of the Grande River. This was Portuguese territory, supposedly off limits to ships from other countries, but there were a few British factories in the area and British slave ships often stopped there on the way down the coast.

According to the Voyage of the Slave Ship Salley 17654-1765 website:

“Slave ships typically worked their way up and down a stretch of coastline. The Sally, in contrast, seems to have spent most of its time in one place, apparently the site of a small British factory. Judging from the account book, the Sally operated as a kind of rum dispensary, supplying passing slave ships with the rum they needed to conduct business on the coast and receiving in exchange manufactured goods like cloth, iron, and guns, which were in turn exchanged for supplies or captives. When food stocks ran low, the Sally's captain, Esek Hopkins, bartered with locals or dispatched one of the Sally's boats up the coast to Bolor, a rice-trading settlement on the Cacheu River.

Slaves slowly trickled in, usually one or two at a time, some purchased from local slave traders, others from passing slave ships. On several occasions, Hopkins dispatched a boat to "Jabe" – probably Geba, a trading center up the Geba River – to purchase small lots of captives. By the time the Sally finally embarked for the West Indies, in August 1765, Hopkins had acquired a total of 196 Africans, some of whom he then sold to other traders. Nineteen Africans had already died on the ship, and a twentieth was left for dead on the day the ship departed. . . .

August 28, 1765: Slaves Rose on us was obliged fire on them and Destroyed 8.

Four more Africans died in the first week of the Sally's return voyage. On August 28, desperate captives staged an insurrection, which Hopkins and the crew violently suppressed. Eight Africans died immediately, and two others later succumbed to their wounds. According to Hopkins, the captives were "so Desperited" after the failed insurrection that "Some Drowned them Selves Some Starved and Others Sickened & Dyed. . . .

The Sally reached the West Indies in early October, 1765, after a transatlantic passage of about seven weeks. After a brief layover in Barbados, the ship proceeded to Antigua, where Hopkins wrote to the Browns, alerting them to the scope of the disaster. Sixty-eight Africans had perished during the passage, and twenty more died in the days immediately following the ship's arrival, bringing the death toll to 108. A 109th captive would later die en route to Providence. . . .

November 16, 1765: Sales of Negroes at Public Vendue.

When they dispatched the Sally, the Brown brothers instructed Hopkins to return to Providence with four or five "likely lads" for the family's use. The rest of the Sally survivors were auctioned in Antigua. Sickly and emaciated, they commanded extremely low prices at auction. The last two dozen survivors were auctioned in Antigua on November 16, selling, in one case, for less than £5, scarcely a tenth of the value of a ‘prime slave.’”

Brassa Nchabra survived the brutal middle passage across the Atlantic and was brought to Charleston, South Carolina just prior to the American Revolution.

In Charleston, the sale of Brassa Nchabra created his first “profit” for the enslavers. The National Parks Service Historic Website reports that,

“Henry Laurens was born in Charles Town in 1724. He was the grandson of French Huguenot immigrants who were members of the Reformed Church that was established by John Calvin in 1550.3 They fled to England and then Ireland after the revocation of the Treaty of Nantes finally immigrating to New York City. In 1715 the Laurens family settled in Charles Town where they became very wealthy.

Henry, the first son in the family, was educated in Charles Town and worked in a local counting-house. He was sent to England by his father to learn a trade . He trained under a prominent British merchant. He returned to South Carolina in 1747. At this time, planters were able to ship their rice directly to ports south of Cape Finisterie in Spain. This made Charles Town the busiest port in America. In 1748 Henry opened an import export business in Charles Town, Austin and Laurens. He made contacts while in London that he entered the slave trade with, Grant, Oswald & Company (the company that controlled the slave outpost Bunce Castle located in Sierra Leone). His company contracted to receive, catalog and market slaves by conducting public auctions in Charles Town. They handled the sale of over 8,000 Africans. The firm also traded in Carolina Gold rice, indigo and deerskins, tar, pitch, silver and gold. They also sent Colonial merchandise to England on returning ships. For this the company received 10% commission on slave cargoes. The expenses incurred while providing for the slaves between landing and the sale and accountability for debts were the responsibility of Austin and Laurens. They were expected to remit accounts after the sales were made regardless of when they were actually paid. They allowed planters up to six months to pay them. Laurens reported netting between 8% and 9% from his share of the sales of slave cargoes. Henry was a slave merchant documented to have been involved in the sale of over 68 cargoes of slaves . . .”

The Asuten and Laurens contract represents the start of the official “lawful” sanction of Brassa Nchabra’s trafficking, enslavement and genocide in the South Carolina colony that would become part of The United States of America.

According to the Negro Law of South Carolina (1740), Section I declared

“all Negroes and Indians (Free Indians in amity with this Government, Negroes, mulattoes and mestizos, who are now free excepted) . . . and all their issue and offspring, born or to be born, shall be . . . hereby declared to be, and remain forever hereafter, absolute slaves. . . .to be chattels personal, in the hands of their owners and possessors, and their executors, administrators, and assigns, to all intents, constructions and purposes whatsoever; . . . Provided always, that if any Negro, Indian, mulatto or mustizo, shall claim his or her freedom, it shall and may be lawful for such Negro, Indian, mulatto or mustizo, or any person or persons whatsoever, on his or her behalf, to apply to the justices of his Majesty's court of common pleas, by petition or motion, either during the sitting of the said court, or before any of the justices of the same court, . . . And the defendant shall and may plead the general issue on such action brought, and the special matter may and shall be given in evidence, and upon a general of special verdict found, judgment shall be given according to the very right of the cause, without having any regard to any defect in the proceedings, either in form or substance; . . . And if judgment shall be given for the plaintiff, a special entry shall be made, declaring that the ward of the plaintiff is free, and the jury shall assess damages which the plaintiff's ward hath sustained, and the court shall give judgment and award execution, against the defendant for such damage, with full costs of suit; but in case judgment shall be given for the defendant, the said court is hereby fully empowered to inflict such corporal punishment, not extending to life or limb, on the ward of the plaintiff, as they, in their discretion, shall think fit; . . .Provided always, that in any action or suit to be brought in pursuance of the direction of this Act, the burthen of the proof shall lay on the plaintiff, and it shall be always presumed that every Negro, Indian, mulatto, and mustizo, is a slave, unless the contrary can be made appear . . . .”

However, Section 4 stated that

“The term Negro is confined to slave Africans (The ancient Berbers) and their descendants. It does not embrace the free inhabitants of Africa, such as the Egyptians, Moors, or the Negro Asiatics, such as Lascars. . .”

Thus, by this statute, B’rassa Nchabra, who was a free inhabitant at the time of his capture and came from a family lineage and people that had never been enslaved and were not subjects of any political authority, was wrongfully enslaved in Charleston through illegal English maritime activity and statutory law and South Carolina statutory law.

Being so young and unable to speak English, he could not make a case in defense of his freedom upon arrival in Charleston.

[Siphiwe Note: Here, the English in South Carolina were following after the Portuguese. Herman L. Bennett, in African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossession in the Early Modern Atlantic, “

. . . . Portuguese awareness of differences among Africans. Accordingly, it was the Moor, who, because of his superior status, valued freedom more than blacks. The Portuguese quickly equated status with sovereignty and the lack thereof with the legitimate enslavement of certain individuals. Though the Portuguese captured both Moors and the ‘black Mooress,’ they had already started distinguishing between sovereign ‘Moorish’ subjects and those ‘Moors,’ ‘Negros,’ and ‘black’ that they could legitimately enslave. Zurara observed that the ‘black Mooress,’ unlike the valiant yet vanquished ‘Moor,’ represented the ‘legitimately’ unfree. . . . As the Portuguese encountered more of Guinea’s inhabitants the terms ‘Black Moors’ ‘blacks,’ “Ethiops,’ ‘Guineas,’ and ‘Negroes,’ or the descriptive terms to which a religious signifier was appended such as ‘Moors. . . [who] were Gentiles’ and ‘pagans’ gradually constituted the rootless and sovereignless – and in many cases, simply ‘slaves’. . . . the Portuguese introduced a taxonomy that distinguished Moors from blackamoors, infidels from pagans, and Africans from blacks, sovereign from sovereignless subjects, and free persons from slaves. ]

B’rassa Nchabra was forced to accept the name “George” - named after the infamous slave owner and traitorous leader of the Sons of Liberty terrorist group, George Washington.

George was subject to the following laws in South Carolina which today are considered violations of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Section 3, 24 and 36. George was not allowed to leave plantation without permission or being accompanied by a white man. The punishment was “whipping on the bare back, not exceeding twenty lashes”. If George refused to submit or undergo the examination of any white person, it was lawful for any such white person to pursue, apprehend, and moderately correct George; and if he resisted, defended himself, or struck a white person, he could be lawfully killed.

Section 7, 23 and 43. George was not allowed to gather together with other slaves nor possess arms, ammunition or stolen goods. Gathering together with more than seven slaves was punishable by up to twenty lashes on the bare back.

Section 16. If George set fire to, burned or destroyed any sack of rice, corn or other grain, tar kiln, barrels of pitch, tar turpentine or rosin, take or carry away any slave or maliciously poison or administer any poison to any person the penalty was death.

Section 17. Any attempt at insurrection or enticing a slave to run away was punished by public execution to deter other.

Section 21. George could be forced to whip or kill another slave, and if he refused, the punishment was whipping on the bare back, not exceeding twenty lashes.

Section 30 and 31. George was not allowed to buy, sell, deal, traffic, barter, exchange or use commerce for any goods, wares, provisions, grain, victuals, or commodities, of any sort or kind whatsoever. All such goods would be seized and the punishment was a public whipping on the bare back, not exceeding twenty lashes.

Section 32. Alcohol was forbidden.

Section 34. George was not allowed to have a boat, canoe, horse, cattle, sheep or hogs.

Section 36. George was not allowed to beat drums, blow horns, or use any other loud instruments.

Section 40. George was not allowed to have or wear any sort of apparel whatsoever, finer, other, or greater value than Negro cloth, duffels, kerseys, osnabrigs, blue linen, check linen or coarse garlic, or calicoes, checked cottons, or Scotch plaids.

Section 41. George was not allowed to rent or hire any house, room, store or plantation, on his own account.

Section 45. George was not allowed to read or write.

These laws sanctioned the “lawful” use of terroristic force in the form of corporeal punishment - whippings and death. They deliberately sought to kill members of the enslaved group; cause serious bodily and mental harm to members of the enslaved group; and inflict on the enslaved group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part. The effect was to produced trauma in George, the victim and the targeted community that imprinted the brain with a familiarity heuristic that said,

“don’t leave the plantation without permission, be obedient, serve the master, never strike back or revolt if you want to survive. You must learn to tolerate slavery.”

For the first time in the history of the Brassa Nchabra lineage, such trauma and SUBSERVIENCE was imprinted in their ancestral genetic memory forever altering brain function and behavior.

Around 1788, George had a son named Jack, the first person in the history of Brassa Nchabra’s family, to be born into slavery or any kind of servitude. The fate of George is unknown, but Jack was brought to Wake County, North Carolina and given to Dempsey Blake, the great, great grandson of the pirate Robert Blake.

The Slaveholding Blake Family

Robert Blake was himself a rebellious traitor, fighting against his King during an English civil war and defeating Royal General Prince Rupert in 1650. For this, Robert Blake was given legal sanction for his mercenary actions by being designated Commander-in-Chief of the English Fleet. He stole $14 million worth of goods from a Spanish fleet and used this money and his status to send his sons to America and establish lucrative plantations. His descendants would become some of the largest slave owners in America.

Thomas Blake, grandson of the traitorous pirate Robert Blake, came to Virginia Colony before 1664 and settled in Isle of Wight County. He was a man of affairs, owning considerable property and received numerous grants of land, some of which were for transporting emigrants to Virginia for colonization. . . . On April 10th, 1704, Thomas deeded 100 acres to his son, William Blake, both then being of the Upper Parish of said County, Isle of Wight, Va, just north of the border with North Carolina. . . . At the time Thomas gave William a deed for 100 acres, Nicholas Sessums gave a similar deed for a 100 acres to his daughter, Mary Blake, and his son-in-law William Blake as marriage gifts. . . . Nicholas Sessums was a man of much property, owned 1000 acres of land and numerous slaves . . . .

William Blake’s son, Joseph Blake moved to Wake County, North Carolina.

His father, William Blake, while still alive, deeded to Joseph negroes named Sampson, Jack (and son) and Ned.

Joseph Blake also had the following male slaves - Toby, Bristol, Prince, Billy, Mayro, [unreadable], Jack, Manny - and female slaves - [Sappo? and child], Dianna, Barbara, Maria and child, [Shena?], Betty, Dolly, Judy and [unreadable].

Joseph Blake had a son named Dempsey Blake in 1757. On August 19, 1771, Joseph Blake died. Probate records show that his wife Mary hired out four slaves and that there was a close connection to Walter Blake.

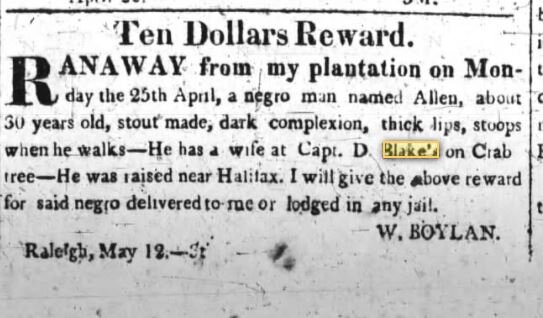

By 1790, in the state of North Carolina, there were 288,204 white people, 100,572 slaves, and 4,975 free people of color. In Wake County, there were 10,192 people including 7,549 white people, 2,463 slaves and 180 free persons of color. Many slaves in Wake County tried to escape. In 1814, Dempsey Blake offered a ten dollar reward for an escaped slave named Allen.

Jack Blake

It is not known what happened to Brassa Nchabra, but his son Jack was given to Dempsey Blake. From the above records, Joseph Blake did, indeed, own a slave named Jack who had a son, but this Jack would be too old and doesn’t fit our timeline. However, there may be some connection. Nevertheless, in 1819, Dempsey Blake deeded to his son Asa Blake “the negro named Jack.” This is my great, great, great, great grandfather.

That same year, 1819, Yancey Blake was born, according to the 1870 Census which lists Yancey Blake as 51 years of age. In Yancey’s household is Lydia Blake, aged 70 (born about 1799-1800), who most likely was his mother.

In 1850 Asa Blake deeded to his beloved wife Catherine “Siddy/Liddy” Hartsfield-Blake, the “negro Jack and Yancey. and also a negro woman [C]ealy and Matilda“ . Yancey would have been about 30 years of age and Jack would have been between 50 and 65 years of age.

Perhaps it is from Siddy/Liddy Blake that Yancey’s mother “Lydia” Blake is named. Lydia would have been about 50 years of age. However, according to the 1860 Slave Schedule for Wake County, NC, there was a slave owner named Lydia Blake.

By 1853, according to the Marriage Register for Wake County, it appears Catherine “Siddy/Liddy” Hartsfield-Blake emancipated Jack, though no emancipation record has yet been found. Emancipating a slave was very difficult at that time. A slave had to be over the age of fifty and the owner had to petition the court, prove “meritorious service beyond general duties” and pay $500 to $1,000 dollars. Emancipated slaves were then forced to leave the state withing 90 days.

Historian John Hope Franklin writes in The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860,

“The effort of North Carolina to discipline the free Negro and to prevent his overturning the established order resulted in the reduction of the free Negro’s position to one of quasi-freedom . . . The same circumscriptions that served to hamper the free Negro in the legal and economic spheres were present as he sought a place in the social life of the state. The walls of restriction that almost completely encircled him cut many of the lines of communication between him and the larger community.”

Ira Berlin states in Slaves without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South,

“once free, blacks generally remained at the bottom of the social order, despised by whites, burdened with increasingly oppressive racial proscriptions, and subjected to verbal and physical abuse.”

John Spencer Bassett states in Slavery in the State of North Carolina,

“Slaveholders disliked and feared free negroes because they demoralized the quiet conduct of the slaves. These negroes were under no direct control of the white man. They might aid the slaves in planning a revolt, in disposing of stolen property, in running away, and in any other act of defiance. Privilege after privilege was withdrawn from them. At first they had most of the rights and duties of the poor white man; they fought in the Revolutionary armies, mustered in the militia, voted in the elections, and had their liberty to go where they chose. At length they lost their right to vote; their service in the militia was restricted to that of musicians; and the patrol came more and more to limit their freedom of travel. Taxes and road duty alone of all their functions of citizenship were at last preserved . . . .The legal status of the free negro was peculiar. Was he a freeman, or was he less than a freeman? The former he was by logical intent; yet he was undoubtedly denied . . . many rights which mark the estate of freemen. . . . In the triumph of the pro-slavery views, about 1830, the free negro was destined to lose the franchise. The matter came to a head in the Constitutional Convention of 1835. . . . [I]t was argued that a free negro was not a citizen, and that if he had ever voted it was illegally. Being called freemen in the abstract did not confer on them the dignity of citizenship any more than it made citizens of the slaves. . . . A slave was not a citizen. When was a freed slave naturalized? And until naturalized could he be a citizen? . . . The cold logic of the views of the majority was stated by Mr. Bryan, of Carteret, as follows:

‘This is, to my mind, a nation of white people, and the enjoyment of all civic and social rights by a distinctive class of individuals is purely permissive, and unless there be a perfect equality in every respect it cannot be demanded as a right. . . . I do not acknowledge any equality between the white man and the free negro in the enjoyment of political rights. The free negro is a citizen of necessity and must, as long as he abides among us, submit to the laws which necessity and the peculiarity of his position compel us to adopt.’

Mr. McQueen, of Chatham, continued the argument: the Government of North Carolina did not make the negro a slave, said he. It gave the boon of freedom, but did that carry the further boon of citizenship? . . . More relentless still was Mr. Wilson, of Perquimons. He said:

‘A white man may go to the house of a free black, maltreat and abuse him, and commit any outrage upon his family, for all of which the law cannot reach him, unless some white person saw the act committed - some fifty years of experience having satisfied the Legislature that the black man does not possess sufficient intelligence and integrity to be entrusted with the important privilege of giving evidence against a white man. And after all this shall we invest him with the more important rights of a freeman? . . .

After the discussion had continued two days, the matter was carried against the free negro by a vote of 65 to 62. . . .

After the severe laws of the third and fourth decades of the nineteenth century opinion changed. It was that it was as late as 1844 that the Supreme Court undertook to fix the status of the free negroes. It then declared that ‘free persons of color in this State are not to be considered as citizens in the largest sense of the term, or if they are, they occupy such a position as justifies the Legislature in adopting a course of policy in its acts peculiar to them, so that they do not violate the great principles of justice which lie at the foundation of all law. . . . There were more free negroes in North Carolina in 1860 than in any other State except Virginia. . . . They took the poorest land. Usually they rented a few acres; often they bought a small ‘patch’ and on it dwelt in log huts of the rudest construction. . . .”

According to the Marriage Register for Wake County, the first thing Jack Blake did with his freedom was to marry Cherry Blake on October 10, 1853. Again, if Jack was between the ages of 20 and 30 when Yancey was born (in 1819), then that would make the birth of Jack sometime around 1788 and 1798. Thus, Jack would be in his 50’s or 60’s at the time of his marriage to Cherry Blake, and qualified for emancipation.

Here is the list of all the slaveholders named Blake in Wake County, North Carolina according to the

1860 Federal Census Slave Schedule

The Civil War

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina issued its Declaration of Secession from the United States of America. On April 12, 1861, the South Carolina Militia bombarded Fort Sumter forcing the surrender of the United States Army. This was the first battle initiating America’s Civil War. On May 20, 1861, Raleigh hosted a Secession Convention, which resulted in N.C. breaking from the Union. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln, issued the Emancipation Proclamation ending slavery. The use of Negro troops in the Union army later in the year, made American Negroes feel sure that a new day had dawned for them.

Raleigh largely escaped the devastation of direct action until 1865, as Major General William T. Sherman's Union forces entered N.C. and maneuvered their way towards the capitol while pursuing General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate Army of Tennessee. Skirmishes took place in and around Raleigh near Morrisville and Garner. On April 12, Governor Vance sent a commission, including former governors David Swain and William A. Graham to meet with Sherman to offer the surrender of the city. The official surrender took place the next day, with the promise that the town would be spared the destruction dealt to Columbia, S.C. According to Eustace Blake, “During the civil war a group of Federal Soldiers came past the house of my grandfather (Yancey Blake, son of Jack Blake), Yancey Blake Jr. (Jack Blake’s grandson) joined them and was never heard from anymore.” (see below).

The North Carolina Slave Narratives records have many eyewitness accounts from the point of view of slaves. Below are some of the testimonies from former slaves living in Wake Co. at the time:

Jane Lee (b. 1856)

“I wus borned de slave of Marse Henry McCullers down here at Clayton on de Wake an’ Johnson line. . . . Marse Henry had six or seben [slaves]. . . . I ‘members de Yankees comin’ good as iffen hit wus yesterday. Dey comed wid a big noise, chasin’ our white folks what wus in de army clean away. De chase dem to Raleigh an’ den dey kotch ‘em, but dey ain’t had much time, ter do us any damage case dey wus too busy atter der Rebs. De woods wus full of runaway slaves an’ Rebs who desered de army so hit wus dangerous to walk out. Marse Henry give us a speech about hit an’ atter I seed one rag-a-muffin nigger man dat wus so hongry dat his eyes pop out, I ain’t took no more walks. Atter de war we moved on Mr. Ellington’s place wid daddy an’ dar I stayed till I married . . . .”

CLARA JONES (b. 1852) 408 Cannon Street, Raleigh, North Carolina, Wake Co

"I doan know how old I is but I wus borned long time ago case I wus a married 'oman way 'fore de war. We lived on Mr. Felton McGee's place hear in Wake County. I wurked lak a man dar an' de hours wus from sunup till dark mostly. He ain't had but about fifty slaves but he makes dem do de wurk of a hundret an' fifty. We ain't had no fun dar, case hit takes all of our strength ter do our daily task. Yes'um we had our tasks set out ever' day.

One day, right atter my fifth chile wus borned, I fell out in de fiel'. Marster come out an' looked at me, den he kicks me an' 'lows, 'a youngin' ever' ten months an' never able ter wurk, I'll sell her'.

"A few days atter dat he tuck me an' my two younges' chilluns ter Raleigh an' he sells us ter Marse Rufus Jones. Marse Rufus am a good man in ever' way. He fed us good an' he give us good clothes an' we ain't had much wurk ter do, dat is, not much side of what we had ter do on McGee's plantation. We had some fun on Marse Rufus' plantation, watermillion slicin's, candy pullin's, dances, prayer meetin's an' sich. Yes mam, we had er heap of fun an' in dat time I had eleben chilluns.

My husband, William, still stayed on ter Mister McGee's. We got married in 1860, de year 'fore de war started, I think. I can't tell yo' much 'bout our courtin' case hit went on fer years an' de Marster wanted us ter git married so's dat I'd have chilluns. When de slaves on de McGee place got married de marster always said dat dere duty wus ter have a houseful of chilluns fer him.

When de Yankees come Mis' Sally, Marse Rufus' wife cried an' ordered de scalawags outen de house but dey jist laughs at her an' takes all we got. Dey eben takes de stand of lard dat we has got buried in de ole fiel' an' de hams hangin' up in de trees in de pasture. Atter dey is gone we fin's a sick Yankee in de barn an' Mis' Sally nurses him. Way atter de war Mis' Sally gits a letter an' a gol' ring from him. When de news of de surrender comes Mis' Sally cries an' sez dat she can't do widout her niggers, so Marse Rufus comes in an' tells us dat we can stay on. William moves ober dar, takes de name of Jones an' goes ter farmin' wid a purpose an' believe me we makes our livin'. We stay dar through all of de construction days an' through de time when de Ku Kluxes wus goin' wild an' whuppin's all de niggers

De white folks went off to de war; dey said dey could whup, but de Lord said, 'No', and dey didn't whup. Dey went off laffin', an' many were soon cryin', and many did not come back. De Yankees come through, dey took what dey wanted; killed de stock; stole de horses; poured out de lasses and cut up a lot of meaness, but most of 'em is dead and gone now. No matter whether dey were Southern white folks, or Northern white folks, dey is dead now.”

JANE LASSITER (b. about 1857) 324 Battle Street Raleigh, N.C. Wake Co

"I am 'bout 80 years old. I am somewhere in my seventies, don't zackly know my age. I wus here when de Yankees come an' I 'member seein' dem dressed in blue. I wus a nurse at dat time not big enough to hold a baby but dey let me set by de cradle an' rock it. We lived in little ole log houses. We called 'em cabins. They had stick an' dirt chimleys wid one door to de house an' one window. It shet to lak a door. We did not have any gardens an' we never had any money of our own. We jest wurked fer de white folks. We had plenty sumptin to eat an' it wus cooked good. My mother wus de cook an' she done it right. Our clothes wus homemade but we had plenty shiftin' clothes. Course our shoes wus given out at Christmas. We got one pair a year an' when dey wore out we got no more an' had to go barefooted de rest of de time. You had to take care of dat pair uv shoes bekase dey wus all you got a year. The slaves caught game sometime an' et it in de cabins, but dere wus not much time fer huntin' dere wus so much wurk to do. Dere wus 'bout fifty slaves on de plantation, an' dey wurked from light till dark. I 'member dey wurkin' till dark. Course I wus too small to 'member all 'bout it an' I don't 'member 'bout de overseers. I never seen a slave whupped, but I 'members seein' dem carryin' slaves in droves like cows. De white men who wus guardin' 'em walked in front an' some behind. I did not see any chains. I never seen a slave sold an' I don't 'member ever seein' a jail fer slaves. Dere wus no books, or larnin' uv any kind allowed. You better not be ketched wid a book in yore han's. Dat wus sumptin dey would git you fer. I ken read an' write a little but I learned since de surrender. My mother tole me 'bout dat bein' 'ginst de rules of de white folks. I 'members it while I wus only a little gal. When de Yankees come thro'.

Dere wus no churches on de plantation an' we wus not 'lowed to have prayer meetings in de cabins, but we went to preachin' at de white folks church. I 'member dat. We set on de back seat. I 'member dat. No slaves ever run away from our plantation cause marster wus good to us. I never heard of him bein' 'bout to whup any of his niggers. Mother loved her white folks as long as she lived an' I loved 'em too. No mister, we wus not mistreated. Mother tole me a lot 'bout Raw Head an' Bloody Bones an' when I done mean, she say, 'Better not do dat any more Raw Head an' Bloody Bones gwine ter git yo'.' Ha! ha! dey jest talked 'bout ghosts till I could hardly sleep at nite, but de biggest thing in ghosts is somebody 'guised up tryin' to skeer you. Ain't no sich thing as ghosts. Lot of niggers believe dere is do'. We stayed on at marsters when de surrender come cause when we wus freed we had nothin' an' nowhere to go. Dats de truth. Mister, dats de truth. We stayed with marster a long time an' den jest moved from one plantation to another. It wus like dis, a crowd of tenants would get dissatisfied on a certain plantation, dey would move, an' another gang of niggers move in. Dat wus all any of us could do. We wus free but we had nothin' 'cept what de marsters give us.”

CHANA LITTLEJOHN 215 State Street Wake Co

"I remember when de Yankees come. I remember when de soldiers come an' had tents in Marster's yard before dey went off to de breastworks. My mother wus hired out before de surrender an' had to leave her two chilluns at home on Marster's plantation. When she come home Christmas he told her she would not have to go back any more. She could stay at home. This wus de las' year o' de war and he tol' her she would soon be free. . . . "I doan reckon I wus ten years old when de Yankees come, but I wus runnin' around an' can remember all dis. Guess I wus 'bout eight years old. I wus born in Warren County, near Warrenton. I belonged to Peter Mitchell, a long, tall man. There were 'bout a hundred slaves on de plantation. "We had gardens and patches and plenty to eat. We also got de holidays. Marster bought charcoal from de men which dey burnt at night an' on holidays. Dey worked an' made de stuff, an' marster would let dem have de steer-carts an' wagons to carry deir corn an' charcoal to sell it in town. Yes sir, dis wus mighty nice. We had plank houses. Dere wus not but one log house on de plantation. Marster lived in de big house. It had eight porches on it.

"Dere wus no churches on de plantation, an' I doan remember any prayer meetin's. When we sang we turned de wash-pots an' tubs in de doors, so dey would take up de noise so de white folks could not hear us. I do remember de gatherin's at our home to pray fur de Yankees to come. All de niggers thought de Yankees had blue bellies. The old house cook got so happy at one of dese meetin's she run out in de yard an' called, 'Blue bellies come on, blue bellies come on.' Dey caught her an' carried her back into de house.

"When de overseer whupped one o' de niggers he made all de slaves sing, 'Sho' pity Lawd, Oh! Lawd forgive!. When dey sang awhile he would call out one an' whup him. He had a sing fur everyone he whupped. Marster growed up wid de niggers an' he did not like to whup 'em. If dey sassed him he would put spit in their eyes and say 'now I recon you will mind how you sass me.'

"We had a lot o' game and 'possums. When we had game marster left de big house, and come down an' et wid us. When marster wan't off drunk on a spree he spent a lot of time wid de slaves. He treated all alike. His slaves were all niggers. Dere were no half-white chilluns dere. "De black folks better not be caught wid a book but one o' de chilluns at our plantation, Marster Peter Mitchell's sister had taught Aunt Isabella to read and write, an' durin' de war she would read, an' tell us how everythin' wus goin'. Tom Mitchell, a slave, sassed marster. Marster tole him he would not whup him, but he would sell him. Tom's brother, Henry, tol' him if he wus left he would run away, so marster sold both. He carried 'em to Richmond to sell 'em. He sold 'em on de auction block dere way down on Broad Street.

"We comed ter Raleigh 'fore things wuz settled atter de war, an' I watches de niggers livin' on kush, co'nbread, 'lasses an' what dey can beg an' steal frum de white folkses. Dem days shore wuz bad."

Reconstruction

On April 26, 1865, Sherman received the unconditional surrender of Johnston's army at Bennett family farm in present-day Durham. The next day the announcement was made public in Raleigh.

On September 29, 1865, almost 150 delegates attended The Convention of the Colored People of North Carolina held at the Loyal AME Church in Raleigh, North Carolina. The President of the convention stated,

“There had never been before and there would probably never be again so important an assemblage of the colored people of North Carolina as the present in its influence upon the destinies of this people for all time to come. They had assembled from the hill-side, the mountains, and the valleys, to consult together upon the best interests of the colored people, and their watchwords, “Equal Rights before the Law.”

The Business Committee made a report

“declaring the first wants of the colored people to be employment at fair wages, in various branches of industry. To secure lands and to cultivate them, and lay up their earnings against a rainy day. Advising the colored people to educate themselves and their children, not alone in book learning but in a high moral energy, self-respect, and in virtuous, Christian, and dignified life.”

A second convention of colored people in Raleigh was held from October 2-5, 1866. The representatives for Wake County included J. H. Harris, of Wake, President of the State Equal Rights League, Marcillus Orford, H. Locket, Charles Ray, William, . Laws, S. Ellerson, J. R, Caswell, Moses Patterson and Williamm. High.

W. E.B. DuBois explains in Black Reconstruction in America: 1860 - 1880:

“When President Johnson called North Carolina whites into consultation concerning his proposed plan of Reconstruction, many of them were highly indignant, some even leaving the room. They did not propose to share power even with the President but wanted to put their own legislature back in power. . . . Here, as in other states, there came the preliminary movement of planters to secure control of the Negro vote. . . . The idea was to forestall any attempt of Northern white leaders and capitalists to control the Negro vote. The Negroes, however, had thought and leadership, both from the free Negro class, who had education, and from colored immigrants from the North, many of who had been born in North Carolina but had escaped from slavery.

During the year 1865, Negroes circulated petitions asking the President for equal rights. . . . A commission was appointed to report on new legislation for the freedmen. This commission reported in 1866 and the General Assembly passed a bill which defined Negroes and gave them the civil rights that free Negroes had had before the war. An apprenticeship law disposing of young Negroes ‘preferably to their former masters and mistresses’’ was passed and Negroes could be witnesses only in cases in which Negroes were involved. In 1867 there were acts to prevent enticing servants, harboring them, breach of contract, and later seditious language and insurrection. . . .

When the Reconstruction Act was under consideration in Congress, the North Carolina Negroes sent a delegation to Washington . . . . In September, 1867, after the Reconstruction Act had passed, the Negro leaders called another convention in Raleigh. . . . This Raleigh convention asked for full rights and full protection and the abolition of all discrimination before the law. . . .

Among the colored people there was growing a strong feeling about the land. Some wanted the land confiscated and given to small farmers. But many of the Northern capitalists opposed this. Harris advocated taxation of large estates so that the land could be sold and opportunity given Negroes to buy . . . By 1868, the ex-planters in North Carolina had begun to organize themselves as Democrats . . .

North Carolina presents quite a different situation and method of Reconstruction . . . . The war left the state in economic bankruptcy. The repudiation of the Confederate debt closed every bank, and farm property was reduced in value one-third. The male population was greatly reduced and the masses were in distress. . . . Thus, the Reconstruction problem in North Carolina, while it had to deal with ignorance and inefficiency, was only to a very small extent a Negro problem. . . . The real fight in North Carolina was between the old regime and the white carpetbaggers, with the poor whites as ultimate arbitrators, and Negro labor between, struggling for existence . . . .

In 1800, North Carolina had 337,764 whites and 140,339 Negroes; in 1840, 484,870 whites and 268,549 Negroes. In 1860 there were 629,942 whites and 361,544 Negroes. There were 30,000 free Negroes in 1860, a class who had in the past received some consideration. Up until 1835 they had had the right to vote and had voted intelligently. . . . In general, however, Emancipation was not attended by any great disorders, and the general tide of domestic life flowed on. . . .

Many things show that in North Carolina land and capital were bidding for the black and white labor vote. Capital with universal suffrage outbid the landed interests. The landholders had one recourse and that was to draw the color line and convince the native-born white voter that his interests lay with the planter-class and were opposed to those of the Northern interloper and the Negro. . . . The Ku Klux Klan increased their activities and the Congressional Investigating Committee reported 260 outrages, including 7 murders and the whipping of 72 whites and 141 Negroes. . . . But the strategy of North Carolina became increasingly clear: to drive out Northerners who dared to take political leadership of Negroes and to unite all whites against Negroes on a basis of race prejudice and mob law. Thus under ‘race’ they camouflaged a dictatorship of land and capital over black labor and indirectly over white labor. The Albermarle Register said: This paper in the future is in favor of drawing the line between whites and blacks regardless of consequences.’ . . . .

The Freedmen’s Bureau issued rations to white people as well as colored, and many were kept from starvation. . . .

On August 19, 1867, the North Carolina Freedmen's Bureau Ration Records,1 865-1872 lists Jack Blake receiving 30 rations for 1 adult male, 1 adult female, and 3 male children.

On May 8, 1868, Jack Blake is listed as receiving 40 rations for 1 adult male and 1 adult female.

According to the Historic and Architectural Resources of Wake County, North Carolina (ca. 1770-1941)

“The war's immediate affects in Wake County were a decline in agricultural production and loss of men. The Confederate Congress had imposed a tax-in-kind on farmers, requiring the payment of one-tenth of most food crops (much of which rotted in warehouses when rail facilities were out of service or tied up transporting soldiers) and also allowed armies to impress provisions with only a promise of payment. Wake County farms in the path of Sherman's Union troops in the spring of 1865 suffered additional losses in livestock and provisions. Between 1860 and 1870, the number of horses in the county dropped by 2,000, milk cows by 1,700, working oxen by 400, sheep by 4,000, and swine by 23,000. Over 60,000 acres of previously cleared land suffered neglect and grew up in brush and new timber, with a corresponding decline of about one-half the production of corn, sweet potatoes, and tobacco. Cotton, oats, and mules were the only agricultural products to exceed prewar levels, suggesting a growing dependence on the fleecy white staple in the immediate postwar years. . . . After slaves were emancipated in 1865, many left their owners and went to work for other planters and farmers or sought a limited number of nonagricultural jobs available in Raleigh and elsewhere. Others remained with former masters and worked for wages. Research conducted by Ransom and Sutch shows that blacks in the postwar South began refusing to work from sunrise to sunset six days a week as they had been coerced to do as slaves.”

By the time of the 1870 Census, Jack Blake (listed as John Blake) and Cherry (listed as Charry) are listed as having 2 sons, John Blake b. 1851 age 19) and Jack Blake (b. 1858 age 12), and one daughter, Sarah Blake (age 15).

Further consideration must be given to the fact that a standard Certificate of Death for a “Jack Blake”, age 55, filed on 11-6-1930 lists “Matilda Blake” as his mother. That means that Matilda had a son named Jack in 1875 (by a man named “Henderson - see below) . It is possible, therefore, that the Matilda given to Siddy (or Liddy, maiden name Hartsfield) Blake by her husband Asa Blake (Dempsey’s son), was the daughter of Jack, father of Yancey because Jack was having children in the 1850’s and Matilda, born around that time, would be of child-bearing age in 1875..

Matilda Blake, age 30, listed in the 1870 Census

Thus, Matilda, the daughter of Jack (and heretofore unknown sister or half-sister of Yancey), named her first son after her father (Jack), the son’s grandfather. Alternatively, Matlida was not related to Jack and Yancey, but was much younger than Yancey, possible a child. In this case, Matilda could have grown up with Yancey Jr.

In addition, North Carolina marriage records show that in 1879, twenty-one-year-old Jack Blake (born around 1858), son of “Henderson” Blake and Matilda Blake, married Amelia Evans in Wake County, North Carolina. This “Henderson” Blake could be Yancey Blake Jr. who ran off to join the Union Army and registered as “Henderson” Blake (see below).

However, this same Jack Blake, now 23 years old, marries Della Hayes two years later in 1881. One of the listed witness in the above Marriage Register for Wake County is “M A Page”. Remember, Uncle Eustace, when he gave the family oral history, said, “Yancey Blake married Melissa Page. Yancey begat nine children by Melissa. Two boys and seven girls. Boys: Yancey Jr and John Addison . . . “

In addition, a standard Certificate of Death from April 24, 1932 in Wake County, North Carolina, for Nona Blake Webster, age 35, lists Jack Blake and Nona Blake as parents. This Nona Blake Webster would have been born in 1897, thus she would be the daughter of Jack Blake (and wife Nona), son of Matilda (who had a son named Jack in 1875.), daughter of Jack or childhood friend of Yancey Jr. given to Asa Blake from his father Dempsey Blake.

Putting it all together in chronological order:

1788-1789: Estimated birth of Jack Blake

1819: Jack Blake given to Asa Blake

1819: Jack Blake age 20 to 30, and Lydia Blake, age 20 have a son Yancey Blake

1847: Yancey has a son named Yancey Jr.

1850: Jack and Yancey Blake along with Matilda given to Catherine “Siddy” Hartsfield-Blake (did Yancey Jr. stay with his mother?)

1850: Yancey Blake and Sabrie Jones have a daughter named Rena Blake

1851: Jack and Cherry Blake have a son named John Blake

1852: Yancey and Sabrie have a daughter named Mallissa (Lissa)

1853: Yancey and Sabrie have a daughter named Lucy Ann

1853: Emancipated Jack Blake marries Cherry Blake (was she free, slave or emancipated?)

1855: Jack and Cherry Blake have a daughter named Sarah Blake

1855: Yancey and Sabrie have a daughter named Nancy Hellon Blake (maybe 1858?)

1856: Yancey and Sabrie have a son Dorsey

1858: Jack and Cherry Blake have a son Jack Jr.

1858: Yancey and Sabrie/Melissa Page have a son John Addison Blake (my 3G grandfather)

1860: Yancey and Sabrie/Melissa Page have a daughter Bettie Blake

1862: Yancey and Sabrie/Melissa Page have a daughter Martha Blake

1863: Yancey and Sabrie/Melissa Page have a daughter Sallie Blake

1866: Yancey and Sabrie/Melissa Page have a daughter Fannie Blake

1867: Jack Blake receives 30 rations for 1 adult male, 1 adult female, and 3 male children (John- age 16; Jack - age 9; and Sarah - age 12).

1868: Jack Blake receives 40 rations for 1 adult male and 1 adult female

1870: Jack Black, listed as “John Blake” in the 1870 Census with wife “Charry” and children John, Sarah and Jack. “John’s” age is listed as 65 but is possible it could be a typo since Jack’s birth day is estimated around 1788 and not 1805….

1880 Census: Cherry “Charry” Blake is listed with son Jack. Thus, her husband Jack died sometime between 1870 and 1880.

1880 Census for Cherry Blake and son Jack

Yancey Blake

Yancey Blake does not appear in the 1860 Census. He would have been 41 years old. This suggests that although Jack Blake was emancipated soon after 1850 by Siddy Blake, Yancey didn’t qualify for emancipation since he was not over the age of 50. Thus, he was most likely still enslaved in 1860.

According to the Historic and Architectural Resources of Wake County, North Carolina (ca. 1770-1941)

“There were seventeen farmers and thirty-seven other members of Wake's free black population who owned real estate in 1860. Four farmers in this class had holdings ranging in value from $2,500 to over $20,000, while seventeen were small-scale slaveowners. Most in this class worked as farmhands. Others were blacksmiths, millers, shoemakers, or carpenters, with a few women listed as seamstresses. A late nineteenth-century historian of free blacks In North Carolina described their houses as "flimsy log huts, travesties In every respect of the rude dwellings of the earliest white settlers. . . .

Slave and free laboring classes shared the same basic work schedule--sunup to sundown with a midday break of an hour or two. At night or in early morning, slaves often tended to vegetable gardens, potato patches, or livestock and some raised their own produce for consumption or trade. Women had such night-time duties as carding, spinning, weaving, and sewing. 'Disobedience or merely failing to work hard enough to please one's master or mistress often resulted in cruel beatings, but slaves could escape such treatment by running away and hiding for several days.”

Unfortunately, in 1861, North Carolina lawmakers barred any black person from owning or controlling a slave, making it impossible for a free person of color to buy freedom for a family member or friend. Thus, Jack Blake was prevented from obtaining the freedom of his children and grandchildren. Thus, Yancey Jr., Jack’s grandson, ran off the plantation and in 1865 enlisted in the 40th U.S. Colored Troops as “Henderson Blake”.

An interesting connection, remember, is that in 1879, twenty-one-year-old Jack Blake (born around 1858), is listed as the son of “Henderson” Blake and Matilda Blake. Did Henderson Blake return after the war? Could Yancey Jr., in fact, be Henderson Blake, who married his childhood friend Matilda?

Again, the 1870 Census lists Yancey Blake, 51. as a farmer.

Ella Arrington Williams-Vinson states that the Blakes owned land in Cary, North Carolina prior to the Civil War in her book, Both Sides of the Tracks II: Recollections of Cary, North Carolina 1860 -2000: “ THE COLORED FAMILIES – All landowners before the 1860’s were the Bateses, Hawkinses, Blakes, Nicholases, Roths, and Joneses – the earliest Colored families in Cary….”. This would suggest that Jack Blake owned land after his emancipation in 1853.

On Christmas Eve, 1874, Yancey Blake received a grant of land, 12 acres, from William and Martha Young.

Again, according to the Historic and Architectural Resources of Wake County, North Carolina (ca. 1770-1941)

“The North Carolina General Assembly of March 1867 passed a crop lien law entitled, ‘Act to Secure Advances for Agricultural Purposes,’ while Conservative Democrats from the antebellum ruling elite were still in power. Soon blacks and whites alike became entrapped by this system that consumed most of the small producer's profits when settlement time came in late fall. As stated earlier, small landowners sometimes lost their~ property when they could not pay creditors or tax collectors. Tenants often fell into a condition of quasi-enslavement when their landlord was also their creditor.

Yancey’s wife Melissa Page died in 1875 and within two years of receiving the land grant of 12 acres, by 1876, Yancey and Jack R Howell were indebted to R Howell in the amount of “eighteen hundred pounds of mid ling cotton […] for which he hold my note to be due on the first day of Nov. in 1876 and to [incur? the payment of the farm] we do hereby convey to him the articles of personal property to wit …. our ….crop of cotton and corn . . . .”

The 1880 Census lists, Yancey, age 60, widower, living with daughters Bettie (20), Sallie (19) and Fannie (14).

1880 Census

As late as 1884, The Branson’s North Carolina Business Directory, Raleigh, Cary Township list Yancey Blake as owning 12 acres of land worth $66 and a Business Directory lists Yancey Blake as one of two colored farmers in Wake County.

In 1885, Yancey signed a contract for $25 loan, using his crop as collateral.

Yancey Blake Crop Lien to Barbee & Barbee in 1885

The following year, on March 17th, 1886, Yancey made another contract with Catherine Ellis. He was indebted to her in the amount of $25 with interest at 8% per anum. To pay the debt, Yancey conveyed to her a tract of land, the 12 acres he received in 1874.

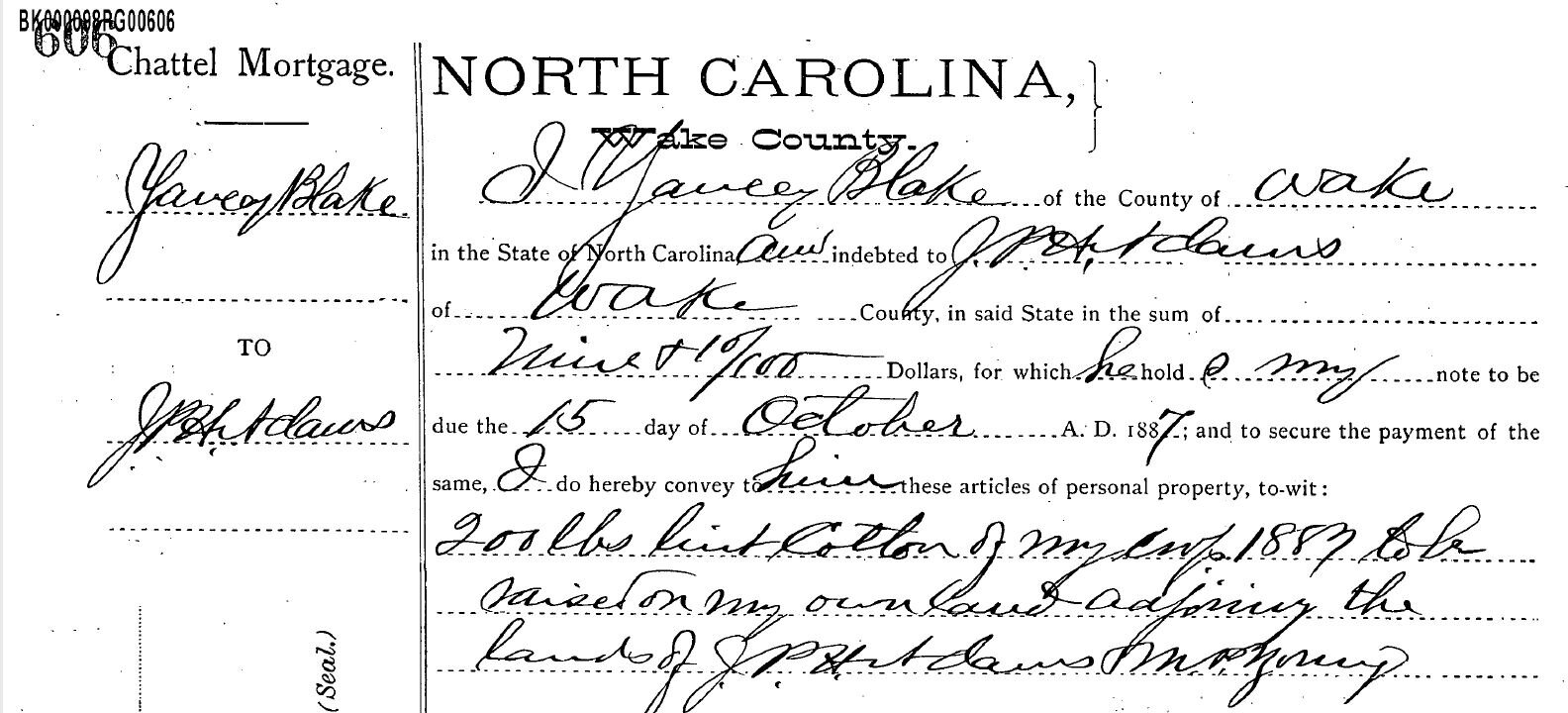

However a year later, Yancey was still indebted to J P Adams in the amount of $9.10 for which he promised to pay 200 lbs. of cotton “raised on my own land adjoining the land of J.P Adams and M. [Martha] Young.”

The Historic and Architectural Resources of Wake County, North Carolina (ca. 1770-1941) states,

“The initial impact of the crop lien system and the resulting shift to cotton growing was more marked in eastern Wake than in southern and western sections. For instance, cotton farmers in Wake Forest Township in the northeast had a 39 percent rate of tenancy among 157 whites and 95 percent among 188 blacks in 1880, whereas only 12 percent of 211 white and 32 percent of 76 black cotton producers in southwestern Wake's Buckhorn Township (including those around New Hill) were tenants that year. Wake Forest area farmers, with richer, more valuable soils and a higher concentration of non-landowning former slaves, tended to take greater financial risks and produced larger crops (generally at least 10 to 20 bales per farm and often as many as 50 to 60 bales)' Meanwhile, in Buckhorn Township described (in the early twentieth century) as a place where people neither starved nor became rich, the majority raised only 1 or 2 wo bales each, while all but nine produced no more than 10 bales each. . . . Sharecropping arrangements provided neither management skills nor opportunities for advancement, particularly for blacks, as store accounts drained most capital they might have invested in homes or farms. Moreover, competition from India following the Civil War gradually drove down cotton prices from 25 cents per pound in 1868 to only 5 cents by 1894, with no corresponding decreases in costs of fertilizer, bagging, machinery, and railroad transportation. As more and more farmers in Wake County and elsewhere in the South came to depend on cotton to pay their bills, the deeper they fell into debt and tenant farming. ”

Around this time, Yancey died and John Addison became the sole surviving son to carry on Yancey’s lineage. However, the lineage of Jack Black continued through Yancey’s brothers Jack and John.

YANCEY BLAKE FAMILY TREE

John Addison Blake

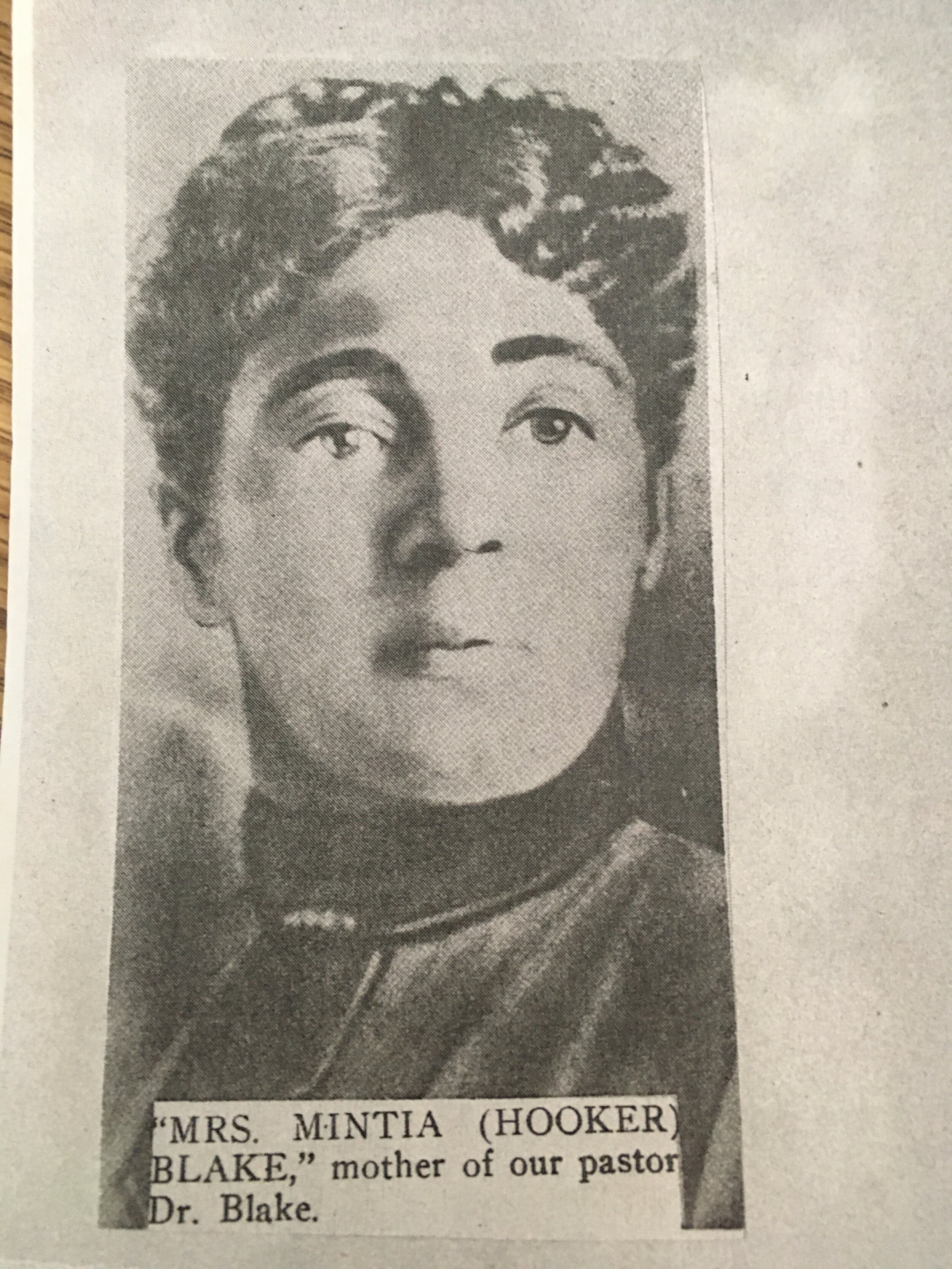

Jack’s other grandson, John Addison Blake, married Mintia Hooker on November 15, 1878. He fell victim to Reverend Charles Colcock Jones’s plan to make the rebellious slaves docile by “Christianizing” them through a deliberate campaign to teach them Christian subservience. John Spencer Basset, writing in 1899 in his book, Slavery in the State of North Carolina, states,

“It was, indeed, in a harsh spirit that the law came at last to regulate the religious relations of the slave. In the beginning, when the slaves were just from barbarism and freedom, it was thought best to forbid them to have churches of their own. But as they became more manageable, this restriction was omitted from the law and the churches went on with their work among the slaves. . . . The change came openly in 1830, when a law was passed by the [North Carolina] General Assembly . . . .It was enacted that no free person or slave should teach a slave to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or give to a slave any book or pamphlet. This law was no doubt intended to meet the danger from the circulation of incendiary literature, which was believed to be imminent; yet it is no less true that it bore directly on the slave’s religious life. It cut him off from the reading of the Bible - a point much insisted on by the agitators of the North - and it forestalled that mental development which was necessary to him in comprehending the Christian life. The only argument made for this law was that if a slave could read he would soon become acquainted with his rights.

A year later a severer blow fell. The Legislature then forbade any slave or free person of color to preach, exhort, or teach ‘in any prayer-meeting or other association for worship where slaves of different families are collected together’ on penalty of receiving not more than thirty-nine lashes.’ The result was to increase the responsibility of the churches of the whites. They were compelled . . . to take on themselves the task of handing down to the slaves religious instruction in such a way that it should be comprehended by their immature minds and should not be too strongly flavored with the bitterness of bondage. With the mandate of the Legislature the churches acquiesced.

As to the preaching of the dominant class to the slaves it always had one element of disadvantage. It seemed to the negro to be given with a view to upholding slavery. As an illustration of this I may introduce the testimony of Lunsford Lane. This slave was the property of a prominent and highly esteemed citizen of Raleigh, N.C. He hired his own time and with his father manufactured smoking tobacco by a secret process. His business grew and at length he bought his own freedom. Later, he opened a wood yard, a grocery store and kept teams for hauling. He at last bought his own home, and had bargained to buy his wife and children for $2500, when the rigors of the law were applied and he was driven from the State. He was intelligent enough to get a clear view of slavery from the slave’s standpoint. He was later a minister, and undoubtedly had the confidence and esteem of some of the leading people of Raleigh, among whom was Governor Morehead. He is a competent witness for the negro. In speaking of the sermons from white preachers he said that the favorite texts were ‘Servants, be obedient to your masters,’ and ‘he that knoweth his master’s will and doth it not shall be beaten with many stripes.’ He adds, ‘Similar passages with but few exceptions formed the basis of most of the public instruction. The first commandment was to obey our masters, and the second was like unto it; to labor as faithfully when they or the overseers were not watching as when they were.’ . . All this was natural. To be a slave was the fundamental fact of the negro’s life. To be a good slave was to obey and to labor. Not to obey and not to labor were, in the master’s eye, the fundamental sins of a slave. . . . [Says Lunsford Lane] ‘There was one hard doctrine to which we as slaves were compelled to listen, which I found difficult to receive. We were often told by the minister how much we owed to God for bringing us over from the benighted shores of Africa and permitting us to listen to the sound of the gospel . . . . ‘ On the other hand, many of the more independent negroes, those who in their hearts never accepted the institution of slavery, were repelled form the white man’s religion . . .

Through the teachings of the church many were enabled to bend in meekness under their bondage and be content with a hopeless lot. There are whites to whom Christianity is still chiefly a burdenbearing affair. Such quietism has a negative value. It saves men from discontent and society from chaos. But it has little positive and constructive value. The idea of social reform which is also associated with the standard of Christian duty was not for the slave.

John Addison, having had three generations of fear, terror, and trauma encoded in his DNA, became the first forcibly converted Christian in the history of Brassa Nchabra’s family lineage.

Thus is the early history of the Brassa Nchabra family in the United States. Both me and my cousin #jacobblake, are the great, great, great, great, great grandsons of Brassa Nchabra.

In 1876 United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 held that the federal government would not protect the recently emancipated slaves against murderous violence perpetrated by ordinary White civilians. One hundred years of lynching followed. In 1883, the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 held that the 14th Amendment did not protect the “social” rights of black people in the United States, such as the right to visit restaurants and theatres. In 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 held that imposing the indignity of racially segregated public facilities and services upon black people in America was constitutional. One year after Plessy v. Ferguson, the United States, in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, at 693, undertook to explain how the U.S. Government could impose U.S. citizenship upon the descendants of Brassa Nchabra without their consent: “The Fourteenth Amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country…” However, there was no protection by the U.S. Government before or after Wong Kim Ark, in law or in practice. It would not be until the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts of 1964 and 1965 - nearly a hundred years after Brassa Nchabra arrived in Charleston, SC - that the descendants of Brassa Nchabra would have access to equal protection under the law.