Excerpts from Balanta B’urassa, My Sons: Those Who Resist Remain Volumes 2-3

The ORIGIN OF LEGAL ISSUES CONCERNING BALANTA PEOPLE IN THE UNITED STATES has already been documented. When people violated our ancestor’s Great Belief, set up kings and governments, imposed authority, and forced them to pay taxes, our ancestors either rebelled or migrated.

Balanta B’urassa, My Sons: Those Who Resist Remain Volume 2 documents how the descendants of Baba Amuntu Abansundu (human beings who are black) who had violated the Great Belief, foreign descendants of Baba Amuntu Abamhlope (human beings who are white), and their mixed breed mulatto offspring ALL engaged in enslaving Anu peoples that did not migrate with our ancestors and instead, chose to stay behind in Ta-Meri and Ta-Nihisi (Lower and Upper Egypt). The persecution and enslavement intensified with the rise of Islam and their jihads (conquests) starting in 641 AD and spread across Northern and Western Africa. Our Balanta ancestors avoided war, capture and enslavement by migrating west to escape the invasion from the east and keeping to the southern Sahel corridor to avoid the invasion from the north.

The Destruction of Black Civilization, p. 97 by Chancellor Williams

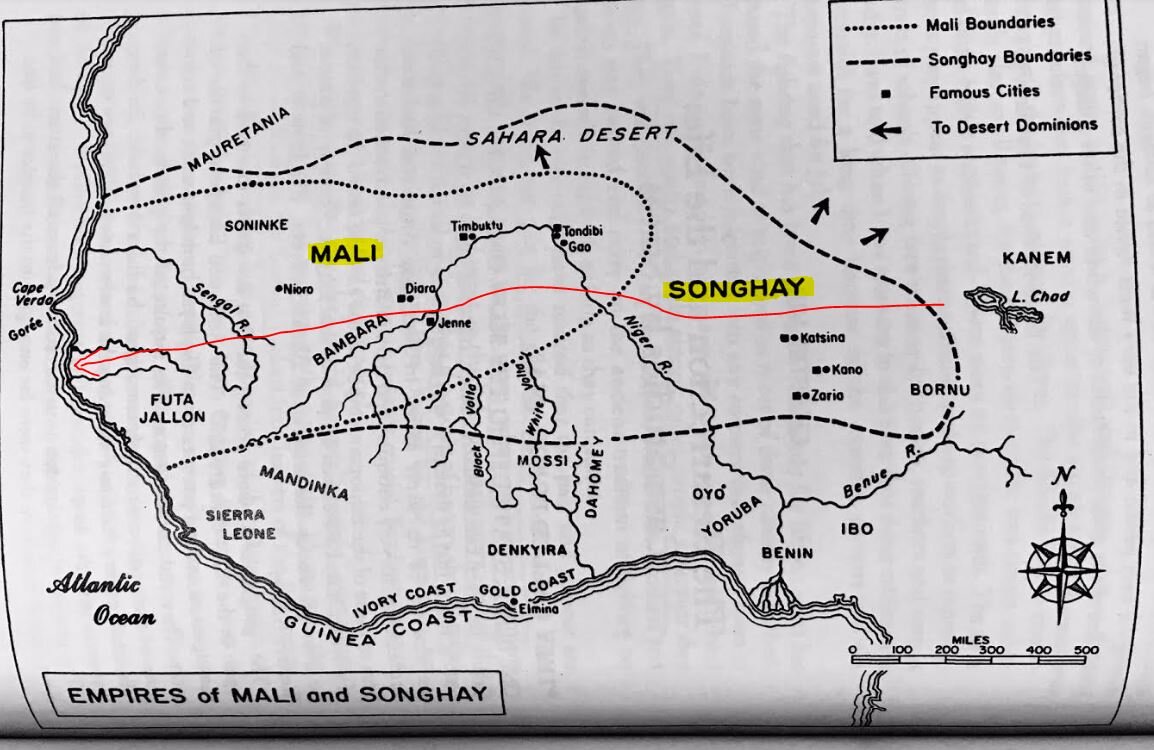

In this way Balanta maintained their freedom for over 4,300 years and did not violate their Great Belief against successive persecutions from the Mesinu (followers of Horus at Edfu), Themehu (Libyans), the Shashu and Habiru (Hyksos), Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Christians, Moslems, Magumi of Duguwa (Kanem) and Tumagera, Ma-Ba-U (Hausa), Soninke of Wagadu (Ghana), Tuareg (Berbers), Almoravids in Wagadu (Ghana), Keita Clan (Mali), the Sunni Dynasty (Songhay), the Askia Dynasty (Songhay), the Moors, Fulbe (Fulani coming from the west), and lastly, by the twelfth century, the Manding of the Kaabu Kingdom. It was the Christian jihad, started in 1424, which would prove to be the undoing for the Balanta that were captured and taken to the Americas.

Balanta Migration

All throughout their migrations, the Balanta suffered persecution from people that wanted to impose their foreign religious beliefs and impose taxes. This is illustrated, for example, in the relationship of the Balanta people and the Soninke people and the Empires of Wagadu (Ghana), Mali, and Songhay. In Exiled Egyptian: The Heart of Africa, Moustafa Gadalla writes,

Ginne

Jenne is the Arabic pronunciation of Ginne/Guinea . . . . which is an ancient Egyptian term meaning ancestor spirit.

The mound, which represents the first site of Ginne (Jenne) has demonstrated the existence of a town of some 80 acres, flourishing from about the mid-8th century to about 1100, and reached its greatest size late in about 850 CE. Genne was founded by Soninke merchants and served as a trading post between the traders from the western and central Soudan and those from Guinea and was directly linked to the important trading city of Timbuktu, located 250 miles (400 km) downstream on the Niger River.

Ancient Ginne (Jenne) thrived until at least 1000 CE. It was a large, heterogenous community of no fewer than 10,000 souls that included specialists providing services to an integrated hinterland. Then, a slow decline in occupation and early abandonment of hinterland villages anticipated final desertion of Ginne (Jenne) about 1400. This was all related to Islamic jihads, by the Keita clan of ancient Mali, and the later expansionist Islamic rulers of Songhai. . . .

The people of Ginne had the same exact founding story as that of Wagadu (ancient Ghana), for both were clearly founded by the Soninke/Sa-u.”

Whenever the Soninke moved west along the Nile river, they found indigenous people already living there. Like the Gow and Do people, our Balanta ancestors also migrated along the river prior to the Soninke and comprised the “integrated hinterland” Gadalla refers to. Why isn’t this known?

Consider what Philip Curtin writes in Chapter 3, Africa North of the Forest in the Early Islamic Age, in African History: From Earliest Times to Independence:

“No simple hypothesis can account for all these cultural patterns [in the Sahel] . . . and no true explanation is likely to be simple. The horizon of written and oral history combined hardly goes back more than a thousand years anywhere along the Sahel, except in the Nile Valley. Add another 3,000 years for the Nile Valley itself and we still cover only a tiny fraction of human experience. Within the time period we know about, however, we have evidence of dramatic changes over a few centuries. . . . .

One striking difference between African and Western history is that Western history is almost always set within the framework of the state. Even during the disturbances after the fall of Rome, the state remained the aspiration, whatever the reality. Partly for this reason, when Europeans first began to consider African history, they took the existence of states as a mark of political achievement – the bigger the state, the bigger the achievement. Recent authorities, however, suggest that this view is far from accurate. At some levels of technology, state administration may only draw off part of the social product for officials and courtiers who contributed little or nothing to create it in the first place. Many Africans apparently reached this conclusion: states and stateless societies have existed side by side over nearly two millennia, without the stateless peoples feeling a need to copy the institutions of their more organized neighbors. Whether statelessness should have been preferable or not, it was clearly preferred.

This fact has left some difficult gaps for historians of Africa. Stateless societies leave few records. Their political operations are far too subtle and complex to be described accurately by early travelers from abroad, whether Arab or European. Oral traditions find no ‘great men’ to celebrate. Genealogies are crucial to the operations of these societies, but people tend to remember everybody’s genealogy for two to five generations rather than that of the ruling family for thirty. As a result, our only information on the way stateless societies changed is that gathered in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet as many as a quarter of all the people in West Africa belonged to stateless societies at the beginning of the colonial period. Historians of earlier periods simply have to leave them out. The only remedy is to look at statelessness in the recent past for hints as to what it might have been like earlier.

Thus, we can understand something about our Balanta ancestors by studying the states with whom they lived adjacent and whom they rejected or resisted becoming a part of in order to maintain their own racial identity, dignity and religion.

Wagadu Commonwealth (Ghana)

“Right after the end of Egypto-Nubian Antiquity,” writes Diop,

“the Empire of Ghana soared like a meteor from the mouth of the Niger to the Senegal River, circa the third century A.D. Viewed in this perspective, African history proceeded without interruption. The first Nubian dynasties were prolonged by the Egyptian dynasties until the occupation of Egypt by the Indo-Europeans, starting in the fifth century B.C. Nubia remained the sole source of culture and civilization until about the sixth century A.D., and then Ghana seized the torch from the sixth century until 1240, when its capital was destroyed by Sundiata Keita. This heralded the launching of the Mandingo Empire (capital: Mali). . . . Next came the Empire of Gao, the Empire of Yatenga (or Mossi), the kingdoms of Djoloff and Cayor (in Senegal), destroyed by Faidherbe under Napoleon III. In listing this chronology, we have simply wanted to show that there was no interruption in African history. It is evident that, if starting from Nubia and Egypt, we had followed a continental geographical direction, such as Nubia- Gulf of Benin, Nubia-Congo, Nubia-Mozambique, the course of African history would still have appeared to be uninterrupted. This is the perspective in which the African past should be viewed. So long as it is avoided, the most learned speculations will be headed for lamentable failure, for there are no fruitful speculations outside of reality.”

Gadalla informs us:

“The new settlers, led by the Soninke, in this most westerly location, formed a confederation that covered much of today’s Mali, parts of Senegal and Mauritania. The Soninke called their new homeland, Wagadu. It is commonly known as the Ghana Kingdom. . . .

Al-Fazari wrote in the 9th century, that Wagadu was known in Morocco as The Land of Gold, suggesting that both Ghana and its trade links with North Africa were well established by the time of his writing. Wagadu was known to pay for trade items, such as salt and luxury items, with gold.

The Soninke also sold food products to desert nomads. Trade routes branched out into a network of intercontinental trade. According to Soninke traditions passed down by word of mouth from one generation to the next, the beginning of their confederation dates back to abut 700 CE. . . .

The Soninke were not the only people who lived in ancient Ghana, but they occupied controlling positions in the political, economic, and other aspects of life. . . . Oral traditions state that the Soninke came from the east, along the Sahel. Oral traditions stress that the locals were ruled by ‘white people’ i.e. light color skin or dark skin with fine features, before Islam arrived.

In 1067-8 CE, the Cordoban geographer al-Bakri put together a fairly comprehensive account of Wagadu, its cities and its trade activities. Al-Bakri remarked that properly Ghana is the title of the king. The name may thus derive from the Malinke word gana or kana meaning chief. The name al-Bakri gives for the king reigning in his day is Tunka Manin, and tunka/timka/dinga means chief in Soninke. . . . “

Soninke oral traditions tell of a time when all Soninke lived together in a place they remember as ‘Wagadu’, but the displeasure of the gods stopped the rain for seven full years. ‘Wagadu’ turned to desert, and the people had to flee to the south.

However, it is important to remember that the Soninke in Wagadu were not friends with Balanta. John Jackson reminds us in Introduction to African Civilizations,

“The Soninke rulers built up an empire by subduing neighboring tribes. This was comparatively easy, since the Ghanaians had fine weapons and tools of iron, and their neighbors did not. Besides iron, Ghana possessed another source of wealth that made it a power to be reckoned with, namely a seemingly inexhaustible supply of gold. . . .

Gadalla continues:

“The Empire of Ghana started out as a kingdom, then annexed other kingdoms, and, like many other kingdoms of the past, evolved into an empire. . . . The Soninkes spoke the Mande language, and in that tongue, Ghana meant ‘warrior king’, and was adopted as one of the titles of the King of Wagadu. Another title of the king was Kaya Magha (‘king of gold’), in allusion to the vast gold treasures of the country. As the fame of the Soninke warrior kings, or Ghanas, spread over North Africa, the people there referred to both the king and the nation over which he ruled as ‘Ghana’. Early Islamic merchants, most of them from Syria, followed the soldiers and administrators into northern Africa. Later, as stability was assured and wealth increased, traders were drawn to the regions of sub-Sahara Africa. Interior trade routes were utilized, and the camel, which had been in general use in North Africa since before the 3rd century, provided the means for traversing the desert. . . . By the 10th century, a number of major trans-Saharan routes had been developed.

Exiled Egyptians: The Heart of Africa by Moustafa Gadalla, p.173

The Arab conquest of North Africa, by the early 8th century CE, concluded with lightning success. In a matter of months, a strip of territory, 100-200 miles deep, was under Arab control – all the way from the borders of Egypt to the Atlantic coast.

The North African and Arabian slave trade was vigorous, and the demand for slaves was high. Islamic law forbade the enslavement of free Moslems but tolerated the continued enslavement of peoples who converted after their capture. In the years of Islamic conquest, the pastoral Berber people had provided the bulk of these slaves. The larger part of the population north of the Atlas Mountains became converts to Islam and therefore could not legally be enslaved.

Starting in the 10th century CE, in order to keep the supply up to the demand, the Arab traders conspired with the nomad Berbers to organize raids, under the guise of Islamic jihads, into neighboring provinces where traditional African religions were practiced. These raids, more than anything, caused many people to declare conversion to Islam prior to being captured, to avoid the horrible raids of killing, kidnapping, enslaving and family break-ups. . . .

Because traditional ancient Egyptian and African religions don’t have a doctrine and are not mobilized in a cult-type camp with rules and regulations, they accept everyone’s right to believe in any way they wish. The Arabs/Moslems enjoyed this right when they settled among the peaceful people. However, the native people became a victim of their own charity.

In order to penetrate the society, Moslem clerics preached ‘social injustice’, a slogan intended to start a class warfare. . . . The preachers of ‘social injustice’ were behind the largest human enslavement in the history of mankind.

Another tactic was for the Moslem/Arab traders to help one side or the other in local disputes, i.e. to get a foothold, and then betray. Divide and conquer.

Though many Moslems lived in Wagadu (ancient Ghana), worked there, and even served the King, the tolerant people treated them fairly and in a friendly way. By 1050, a powerful new force swept through West Africa. A Moslem preacher named Ibn Yacin founded his Almoravid sect, a fanatic group of Moslems. The Almoravids, however, did not return the Ghanaian’s religious freedom in kind.

One of the Almoravids’ targets was Wagadu, whose Kings had repeatedly refused to convert to Islam.

Jihad

The Islamic doctrine calls on Moslems to spread Islam, even by force if necessary. As a result, any Moslem with a superior arm can force his religion by killing others. The unarmed people have no choice but to convert to Islam or die. This self-righteous Moslem may choose instead to enslave any and all members of a non-Moslem family. Spreading Islam by ALL means is not an option, but a duty required by the Islamic doctrine.

There were also sanctions for pursuing the jihad, or holy war, against those who had not been converted. Those who die in battle against non-Moslems, would die in a holy cause.

Each of these Islamic jihads had the same process. Just like any terror campaign, they required financing and hiring of mercenaries. All these terror campaigns started at the beginning point of Islam, i.e. Mecca. The story is the same all along the 2000-mile (3200 km) Sahel. For about 1000 years – a Moslem cleric, or leader, living in Africa, goes to Mecca, gets financial support, and is assigned as a ‘Moslem deputy caliph’ in his African region. He returns to declare Islamic jihad and supplies his masters with more slaves.

It always started with the usual intimidation, a (Moslem) gang will deliver a message to the leader of the peaceful non-Moslem group, to embrace Islam. Once people refuse and/or ignore this unsolicited intimidation, then as shamelessly stated in the Tarikh es Soudan (Soudan Chronicles), the Gangsters declared that it is:

‘Their duty is to fight them and straightaway, the Moslem fighters launched war against them, killing a number of their men, devastating their fields, plundering their habitations, and taking their children into captivity. All of the men and women who were taken away as captives were made the object of divine benediction [converted to Islam].’

Almoravids in Wagadu

In the deserts north of the Wagadu (Ghana) Commonwealth, a Berber group of gangsters, called the Almoravids, started attacking peaceful settlements and villages.

The traditional story of the beginnings of the Almoravids is that Yahia ibn Ibrahim, made a pilgrimage to Mecca. On his return journey, he met Ibn Yacin, whom he persuaded to accompany him to Audaghost, where they preached the practice of Islam. The preaching of Ibn Yacin, however, irritated the people of the area. After the death of Yahia, his protector, Ibn Yacin was forced to retire with his followers to an island in the Senegal River.

Since he couldn’t convince the people to convert to Islam by choice, Yacin followed the Islamic doctrine, to force it by the sword. He proclaimed a jihad, and in 1054 CE, Audaghost fell to the Almoravids. Over a period of five years, between 1054 and 1059, the Almoravid terrorists captured the Moroccan city of Sijilmasa, a hub in the trans-Saharan trade route, and from there commanded ceaseless attacks against the main center of Wagadu (ancient Ghana).

After Ibn Yacin’s death in 1057, a follower nabbed Abu Bakr assumed leadership of the Almoravid terrorist forces in the southern Sahara. In 1062, he began attacking Wagadu. By 1067, the Almoravid terrorists were hammering at the gates of Koumbi, believed to be the main city in Wagadu.

Under King Bassi and his successor, King Tunka Manin, Wagadu resisted heroically for almost a decade. But in 1076 or 1077, the Almoravids were able to destroy the cities and slew many of the citizens and seized their property.

On the death of Abu Bakr in 1087, Almoravid power south of the Sahara simply fell apart. The Almoravids’ stay in Wagadu had been relatively short, but it proved disruptive.

Keita Clan

While the Soninke lived just south of the Sahara Desert, in the Wagadu Confederation, the Malinke occupied mostly the middle and southern parts of the savannah, near the forest belt. There was peaceful coexistence between both the Soninke and the Malinke (Mandinka). Actually, they both belong to the Mande people.

The Keita Clan was one of many groups near the forest belt. They were originally centered in Kangaba, on the Niger River, which was about 250 miles south of Koumbi.

Exiled Egyptians: The Heart of Africa by Moustafa Gadalla, p.173

In 1230, Sundiata was declared the chief of Kangaba. . .

Sundiata Kangaba began to expand his authority by force, in the name of Islam. His forces began the ugly slave raiding and trade, with their Moslem masters. So, Sundiata became the first main sub-Sahara supplier of slaves.

In order for the aggressive Keita gangsters to justify attacking their northern neighbors, they came up with the story that they were threatened by the Soninke. The Almoravid Berbers who couldn’t destroy the Soninke, got Sundiata to attack them.

In 1235, at the battle of Kirina, Sundiata defeated the Soninke army. Five years later, all of Wagadu was incorporated into his domains, destroying a peaceful civilization. Sundiata shifted his place of residence from Jeriba in Kangaba to a new city, Niani, further down the Niger.

The term Mali, meaning where the king lives, came to be applied to the new Mandingo State created by Sundiata’s Keita Clan.”

Mali

Gadalla continues:

“After Sundiata, the rulers of the Islamic empire assumed the title of Mansa, which means emperor or sultan.

Since Sundiata was not in very good health, his immediate successor-son, Uli (c. 1255-1270), began the tradition among the ruling Keita Clan of following the wishes of their Moslem masters, by making a haj, a pilgrimage to the Moslem capital at Mecca, on the Arabian Peninsula. He came back infused with Mecca’s authority to attack his neighbors, in yet more Islamic jihads. Immediately thereafter, the Keita Clan of Kangaba conquered territories, stretching from mid-Senegal to the border of Niger.

The oral history of the Malinke from the 1200s onward stresses the connection of the Malinke to Islam so as to appease their Moslem masters. An outlandish link of Sundiata’s ancestor with Arabia is believed to be an example of this ‘connection.’

The Keita Clan emerged as a dominant power in sub-Sahara Africa, and controlled the trans-Saharan trades from about 1200 to 1500CE. In the days of the Keita Islamic rule, a major trading rout across the Sahara to Tunis and to Cairo, was utilized often, because Moslem rulers needed slaves that the Keita Clan was obliged to provide. The Keita Clan betrayed their own kind, to make riches. Gradually the northeast trade route became the main one.

The new illegitimate dictatorial Islamic rule eliminated the matrilineal succession system. As a consequence, in the thirty years following the death of Sundiata, the Keita Islamic rule had five rulers.

There were three main periods of bloody disorder in the Keita’s rule, created by disputed claims to the throne. The first showed Sundiata succeeded by three sons, Uli, Wali, and Khalifa. The last son, Khalifa, was overthrown in a bloody coup by the adherents of Abu Bakr, considered to be the rightful heir, as the son of one of Sundiata’s daughters. Abu Bakr then took power.

Sakura, a freed slave of the royal family, managed to secure control of the army, and overthrew Abu Bakr’s reign in another bloody coup. Sakura was also overthrown in yet another bloody coup.

The third emperor of the 14th century, a descendant of a brother of Sundiata, was (Kankan) Mousa, who went to the Islamic-besieged Cairo and Mecca, in 1324, where he was infused with authority to attack more neighbors and abduct more slaves, in the name of Islamic jihads.

On his return from Mecca, he conquered Gao and took two of its princes as hostages, along with other children of neighboring communities. These children acted as shields, preventing the Gao people from attacking Mousa’s court.

After Mansa Mousa’s death, probably in 1337, a brief struggle for power ensued before Sulayman, Mousa’s brother, came to the throne in 1341. After his death in 1360, various factions of the Keita Clan began to compete with each other for power, and their hold on power disintegrated.

In short, the empire was maintained by the exercise of dominion of a quasi-Islamic ruling class, by force (al-Umari writes of an army of 100,000, with 10,00 cavalry), for their own profit. As far as the Mande/Malinke subjects were concerned, they have never accepted this illegitimate exercise of power, and were never converted to Islam by their Moslem overlords. They maintained their indigenous traditions.”

Neither were the Balanta ancestors accepting of the illegitimate power, nor did they convert to Islam. Here then, is the ACTUAL point of connection between our most ancient Balanta ancestors, the Anu living in Ta-Nihisi (Nubia, Sudan) and the Balanta living today in Guinea Bissau. Walter Hawthorne writes in Strategies of the Decentralized, in the book Fighting The Slave Trade: West African Strategies by Sylviane A. Diouf:

“The Balanta claim that the region between the Rios Mansoa and Geba – an area they call Nhacra, which is part of the broader region of Oio – is their homeland. The Balanta say that they migrated there ‘in times long past’ from somewhere in the east. In addition, Balanta migration myths have two other common threads: the Balanta left the east because of conflicts with either state-based Mandinka or Fula, and these conflicts resulted from a Balanta propensity for stealing from their more prosperous neighbors or desire to avoid enslavement. For example, elder Estanislau Correia Landim told me, ‘The origin of the Balanta was in Mali. For reasons involving Balanta thefts, Malianos revolted against the Balanta. For this reason, Balanta left there. That is, some Balanta were stealing some things. When a thief was discovered, he resolved to kill the person who had discovered him. For this reason, Malianos chased after the Balanta. . . . When the Balanta left Mali, they went to Nhacra and then to Mansoa.”

After Mansa Musa

John Jackson writes,

“Under [Mansa] Musa I, the Mali Empire embraced an area just about equal to that of western Europe. . . . [T]he lifeblood of the empire was trade; and taxes were the paramount source of income for the government. . . . foreign merchants who traded in Mali marveled at the prosperity of the region and noticed that even the common people were not oppressed by poverty. . . .

When Musa I died in 1332, he was succeeded by his son Maghan. Mansa Maghan was neither as wise nor able as his father, and during this reign Mali went into a decline. First, the city of Timbuktu was lost to enemy forces. . . . Secondly, Mansa Maghan was not alert enough to prevent the escape of the two Songhay princes whom his father had been holding as hostages. The escaped princes returned to Gao, where they established a new Songhay dynasty. Maghan died after a four-year reign, and was succeeded by his uncle, Sulayman – a brother of Mans Musa I. Mansa Sulayman was a sovereign of high competence, and he ably presided over the destinies of Mali until his death in 1359.

The great age of Mali was now at an end; for the later rulers were undistinguished men, under whom the empire disintegrated. About the year 1475, the Songhay Empire, with its capital at Gao, rose to supremacy in the west Sudan, as Mali continued to decline. In 1481 Portuguese sailors landed on the Atlantic coast of Mali. The Mali government attempted to hire these Portuguese as mercenaries to fight the rising power of Songhay, but the proposed alliance was never effected. Mali lingered on for nearly two centuries, but its day of greatness had passed into history, and if finally expired from innocuous desuetude. . . .

Songhay

We have told of the escape of the Songhay princes, Ali Kolon and Sulayman Nar, from their captivity in Mali. Ali Kolon, as legitimate heir to the Songhay throne, followed the last ruler of the Dia dynasty, and established a new line of monarchs called the ‘Sunni’, which means ‘replacement’. During the greater part of the fourteenth century and first half of the fifteenth century, the Sunni dynasty of Songhay gradually extended its sway of the territory of the declining empire of Mali. When in the year 1464, Sunni Ali the Great succeeded to the Songhay throne, an age of great achievements began. The new age was heralded by the capture of Timbuktu, a center of both commerce and culture. It was a place where the river people and the nomads of the desert met for trading purposes; and it was also the seat of the celebrated University of Sankore, which attracted scholars and students from many near and distant lands.

Another great metropolis coveted by Songhay rulers was Jenne, a city established in the thirteenth century by the Soninkes of Ghana. This city was situated in the backwaters of the Benue River (a tributary of the Niger), about three hundred miles southwest of Timbuktu. The Mali had made ninety-nine attempts to capture Jenne during the days of their supremacy in the western Sudan, and finally gave up. But Sunni Ali of Songhay was able to add that city to his expanding domains. After bringing Timbuktu into the fold, he decided that Jenne should be next on his agenda of conquest. The capitulation of Jenne was no pushover, for the siege of the city lasted for seven years, seven months and seven days. . . .

Sunni Ali the Great incorporated much of the territory of the old Mali Empire into his own realm, and before his death in 1492 he had become one of the most famous rulers of his day. In North Africa he was regarded as the greatest sovereign south of the Sahara, and in the annals of Europe we find him mentioned as Sunni Heli, King of Timbuktu, whose empire extended to the coast of the Atlantic Ocean. The son of Sunni Ali inherited the throne and, though nominally a Moslem, he was, like his late father a pagan at heart. Some of his Moslem subjects attempted to convert him to what they regarded as the true faith, but the new sovereign rejected these overtures, taking the position that his personal religious convictions were none of the business of his subjects. The Moslem group staged a revolution, dethroned the incumbent ruler, and elevated Askia Mohammed I, a devout Moslem, to the supreme leadership of the Songhay Empire.

The first sovereign of the Askia dynasty enjoyed much popularity among his Moslem subjects. He relished the society of lawyers, doctors, and students of the Islamic persuasion. . . . Like every good Moslem, he was eager to make the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina; and, in the year 1495, he proceeded to do so, accompanied by an army of 1,000 infantry and a cavalry detachment of 500 horsemen. Some 300,000 pieces of gold were allotted for the financing of this trip. . . . While in Egypt, Askia Mohammed was honored in a special ceremony by the Caliph of Cairo, who appointed him as his personal representative in the Songhay Empire.

Since many neighboring countries were inhabited by pagans, Askia Mohammed considered it his duty as a Moslem potentate to launch a series of jihads (holy wars), in order to bring these infidels into the fold. For example, he annexed the territory of the Mossi, on his southern border, and seized a large number of Mossi children, whom he reared as Moslems and trained for service in his army. In or near the year 1513, the Askia led the armed forces of Songhay into the Hausa States, a complex of kingdoms between Lake Chad and the Niger River. In time all the Hausa States except Kano capitulated. After a siege of one year, the king of Kano sued for peace. . . . After consolidating his Hausa conquests, the Askia subdued the nomad Tuaregs of Air, and settled a Songhay colony in that region. The military record of the Askia was not crowned with complete success, for one kingdom proved itself invincible, Kebbi, a small kingdom, wedged between the Hausa states and the Niger River, was ruled by King Kanta. This ruler, protected by the strong walls of his capital city, was able to maintain the independence of his nation.

Askia Mohammed must be credited with the creation of a strongly centralized government in the Songhay Empire . . . . The most important ministerial posts were the Chief Tax Collector . . . . In the principal cities of West Africa, such as Gao, Jenne, and Timbuktu, universities and other educational institutions were established, and their level of scholarship was of a high caliber. In the schools, colleges, and universities of the Songhay Empire, courses were given in astronomy, mathematics, ethnography, medicine, hygiene, philosophy, logic, prosody, diction, elocution, rhetoric, and music. . . .

When Askia Mohammed ended his career on earth on March 2, 1538, at the age of ninety-seven, he was followed on the throne by his sons, and under their misrule the empire began to fall apart. Daoud, the last son of Askia Mohammed to rule the empire, maintained a stable government from 1549 to 1582. But the great days of Songhay power were now fast approaching an end. In 1585 the salt mines of Taghaza passed into the hands of the sultan of Morocco. This was a disaster to the Songhay Empire, and they were too disorganized to prevent it. Five years later Songhay was invaded by a Moorish army led by Judar Pasha, a Spaniard, captured by the Moors in infancy, and reared in the precincts of the royal palace. This army numbered only five thousand men, but about half of them were armed with firearms imported from England. The superior numbers of the Songhay army were no match for the gunpowder of the Moors. In 1591, both Gao and Timbuktu fell to the invaders from the north. The Moorish forces settled down as an army of occupation and quartered themselves in the Songhay cities for another century and a half. This period completed the decline and fall of the Songhay Empire. ‘From that moment on’, we hear from a contemporary Sudanese scholar, ‘everything changed. Danger took the place of security; poverty of wealth. Peace gave way to distress, disasters and violence.’ At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Golden Age of the western Sudan had reached its nadir.

After the passing of the Songhay Empire, West Sudanic culture moved eastward to the Central Sudan, to Kanem-Bornu and the Hausa States; but none of these nations ever rose to the levels attained by Ghana, Mali, and Songhay in their Golden Age. . . .

The penetration of Islam into the Medieval Sudan was not an unmixed blessing. A judicial appraisal of this question is given in a recent authoritative work dealing with West African history, as follows:

‘The appearance of Islam in the Western Sudan was important for more than religious reasons. It opened many West African states to the influence of Muslims from North Africa and Egypt, and from still further afield, who introduced the arts of writing and scholarship. It insured good trading relations between the Western Sudan and the lands beyond the Sahara, so that contact between Kanem-Bornu and Egypt, Tunisia and Tripoli became valuable and constant. These were clear gains. On the other side it also opened the way for many bitter conflicts between those who accepted Islam and those who did not. Later history has much to say of these religious conflicts. . . .[A History of West Africa to the Nineteenth Century, pp. 84-86, by Basil Davidson].

According to Boubacar Barry in Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade,

“From the twelfth century onward, after the fall of Ghana, the entire Senegambian zone fell increasingly into the direct orbit of the Mali Empirte, which exerted a decisive influence until the fifteenth century and even beyond. It was Mali’s impact that catalyzed the transformation of the regions’ kinship-based societies into states. . . . .At the height of its power, Mali undertook nothing less than a westward colonizing mission, thrusting past the Futa Jallon plateau, then following the river Gambia and the upper valleys of the Casamance, the Rio Cacheu, and the Rio Geba. In the process, the Manding founded the Kaabu Kingdom in the south, along with the principalities of Noomi, Badibu, Niani, Wuli and Kantora, on both banks of the Gambia River. They did this by displacing or absorbing indigenous populations from the Bajar group, together with Jola, Beafada, Papel, Balanta, Bainuk, Baba, Nalu, Landuma, and others, whose descendants today live in the Southern Rivers area between Gambia and Sierra Leone.

In this area without large-scale political units, the level of the people’s adaptation to their natural environment was remarkably high. These peasant societies were egalitarian in outlook. The village was their basic unit, but the collective consciousness was reinforced by the importance of religion. Socialization worked through a system of initiation. . . . it created potent social bonds as well as precious links between humans and nature.

The outstanding feature of life here, however, was undoubtedly the creation of a rice-centered civilization by these populations. For they perfected rice farming techniques on flood plains, using the kayando, a long spade marvelously effective for working wet soils.

The scarcity of documents makes it hard to outline the dynamics of political, social and economic life in Senegambia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. At that time the region was coming into direct contact with Europe by way of the Atlantic. Senegambian societies shared a common civilization in which political and social systems were closely knit, and both were based on an autonomous subsistence economy.

Politically, societies here were initially organized along kinship lines. Later they shifted to a monarchical system based on violence and inequality. The caste system which supported the hierarchical ordering of social life served to rationalize this inequality. . . .

Senegambia had two types of societies. The first, egalitarian in outlook, derived political power from lineage. The second, hierarchical in outlook, imposed monarchical power upon the lineage-based system. . . .

The monarchical system was the logical outcome of the hierarchical ordering of Senegambian societies that began with the rule of the laman or the kafu. Senegambian societies were quintessentially non-egalitarian. The epitome of inequality was the caste system, on which rode a system of subsidiary social divisions, or orders. . . . In all cases, the caste system based on a division of labor, was perpetuated through a biological and racial ideology that imposed hereditary rules and endogamous practices. . . . The Soninke called free men hooro; slaves komo. The Manding called them fooro and joon. The Peul and the Tukulor called free men rimbe and slaves maccube. . . .

Slavery was an ancient institution in the domestic economy of Senegambia, with the exception of the egalitarian Southern Rivers societies. The practice legitimized the division between free persons and slaves. But slavery does not seem to have played a key role in the mode of production, which remained tributary even within the monarchical context. Still, for centuries, slaves were sent in small numbers to the northern markets for sale. Slaves were used as currency in arms deals. During the time of the trans-Saharan trade, they were also used to buy salt, horses and luxury goods – the aristocratic status symbols of the day. Aristocrats sold some slaves, obtained through inter-state warfare, in the inter-regional trading system. Others were turned into domestic slaves, kept to work on family farms or to produce handicraft goods. House slaves were more or less integrated into their masters’ families after one, two, or three generations. There is little evidence for the argument that slavery was the dominant mode of production in Senegambian societies during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.”

Concerning our Balanta ancestors at this time and a little later, Walter Rodney writes,

“The Balantas had quantities of prime yams…. The best farmers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries- the Balantas, the Banhuns, and the Djolas- all had cattle and goats …. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Andre Dornelas pointed out that Balanta territory was free from heavy vegetation. It was these very Balantas who reared the most livestock in the area, and it was they who provided supplies of foodstuffs for their neighbors….That peoples who were far superior producers of food than the Mande and Fula are consistently dubbed ‘Primitives’ is due solely to the contention that they did not erect a superstructure of states. . . .

It is only the Balantas who can be cited as lacking the institution of kingship. At any rate there seemed to have been little or no differentiation within Balanta society on the basis of who held property, authority and coercive power. Some sources affirmed that the Balantas had no kings, while an early sixteenth-century statement that the Balanta ‘kings’ were no different from their subjects must be taken as referring simply to the heads of the village and family settlements. . . .as in the case of the Balantas, the family is the sole effective social and political unit. . . .

Among the Balantas, who are to be classed as a ‘stateless society’, the system of land tenure is different. The Balantas are all small landowners, working their lands on the principle of voluntary reciprocal labor. Thus, when the Balantas clear new areas of swamp for rice cultivation, each one of the working force benefits by receiving a portion of the land reclaimed. Not so with the Papels, however, for they have a well-developed hierarchy of nobles, chiefs and kings who own the land. In their case, land development can only be achieved through the initiative of a rich individual, who can hire the necessary labor; and, since the workers have no stake in the final product, it is not surprising that they have no incentive to undertake the strenuous and demanding job of clearing the swamps. These two contrasting examples indicate that the existence of a superstructure of states was associated with the presence of a land-owning nobility. As with the ownership of the land, so with the distribution of the products – there was manifest inequality.”

THUS, BALANTA MANAGED TO PRESERVE THEIR EGALITARIAN CULTURE BASED ON NATURAL LAW AGAINST SUCCESSIVE ATTEMPTS BY STATE SOCIETIES TO IMPOSE EARLY FORMS OF STATUTORY LAW BASED ON VIOLATIONS OF THE GREAT BELIEF AND NATURAL LAW.