Introduction: African Cultural Carryovers and Epigenetics

The central point of this study is to show that the Balanta tradition of resisting all forms of foreign domination by migrating to unoccupied territory and establishing decentralized organized society based on egalitarian and communal agricultural-based economics while engaging in armed self defense and second strike capacity has been retained in the Americas and is proved by the direct link between Balanta communities in their ancestral homeland, the establishment of the Republic of Palmares in the seventeenth century concurrently with their role in confraternities that pursued a legal case at the Vatican in 1686, and the establishment of the New Afrikan Independence Movement in the United States including the current leadership of both the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika and the global Afrikan Reparatory Justice movement emanating out of the State of Illinois. By examining these, it will show a positive Balanta epigenetic endowment that manifests as an irresistible and irreversible desire for freedom and willingness to escape and/or directly confront alien oppressors, and that this genetic expression is a cultural carryover of Balanta people into the Americas.

Cultural Carryovers

It is a common understanding that Africans have, since the early settlement of the Americas, influenced Americas’ (North, South and Central) language, manners, religion, literature, music, art, and dance. The forms of worship, family organization, music, food, and language developed by Africans held in American slavery can all be seen to bear the signs of African traditional culture, as can the architecture, art, and handcrafts they left behind. However, it is rarely acknowledged that political and military dispositions are also evidence of African traditional culture.

In the abstract for NATIVE AFRICAN ARTS & CULTURES IN THE NEW WORLD; A CASE STUDY OF AFRICAN RETENTIONS IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by Omokaro A.Izevbigie of the Department of Fine/Applied Arts, Faculty of Arts, University of Benin, it states,

“Despite the different languages, and cultures in Africa, there is commonality in religious, artistic and musical traditions. Did the native Africans sold into slavery retain any of the traditions in the “New World” in general and in the United States of America in particular? There is considerable retention in the Latin American countries, because the slaves had many more rights in South America than in the United States. Consequently, the African slaves in the United States of America gradually lost contact with his past. However, there are certain church rituals and some aspects of the black American music which have been identified as cultural carry-overs in the United States.”

Chikodiri Nwangwu writes in Preserving African cultures amid globalization: Lessons from the enslaved communities in the Americas,

“the preservation of cultural identity among the enslaved Africans in the Americas was a key feature of the resistance against cultural assimilation. It is also a testament to their resilience, creativity and adaptability. In his review article published by the University of Chicago Press, R. L. Watson attributed the survival of much of that culture to, among other things, the ratio of blacks to whites, the organization and operation of the plantations, and the predominance of rural settings. Beyond these, however, the will to resist cultural assimilation, which seems absent in many African countries today, was the determining factor. Despite oppressive and harsh working environments, the enslaved Africans devised various ways to maintain their cultural practices, traditions, languages, religions and values.”

But what about the will to resist the actual oppressive agents?

The Balanta example will show that their cultural resistance meant political and military resistance which safeguarded the Balanta cultural value of sovereignty. Importantly, this Balanta cultural expression that preserves independence can be explained by epigenetics.

Transgenerational Epigenetic Effect of Balanta Freedom

What humans inherit from ancestors that makes one unique in personality and behavior, is the genetic and epigenetic material that regulates genetic expression. This genetic material responds to environmental conditions.

In 2020, Dr. Kenneth Knave's published Competent Proof: The Legal Standing for African Americans in the Battle for Reparations reviewing Judge Norgle's decision in the Farmer-Paellmann v. Fleetboston Financial Corp case. In that book, Kenneth S. Nave, MD states,

“Science has proven that environmental conditions shape the structure and function of highly specialized cells in key areas of the body. These changes occur in an extension or appendage to the gene known as the epigene. The epigene is an extension of the gene that responds to biochemical signals emanating from the environment. These signals cause changes to the gene. These epigenetic changes to the gene influence and change the cellular genetics of the cell. . . . Under certain environmental conditions, the epigenome programs or ‘reprograms’ the genetics of the cells of the limbic system which, in its most fundamental definition, is the center of all human thought, emotion, behavior, learning and, when present, psychosocial pathology. . . This environmental shaping is usually pathologic leading to physical disease, social dysfunction, and mental illness. Most significantly to the plight and social conditions of the descendants of former slaves is the scientifically proven fact that the changes to the epigene created by environmental pathology is passed down to the descendants of those initially impacted by environmental gene shaping. . . . As it relates to the cells of the brain, this cellular shaping can lead to problems with learning, memory, and mental health. As it relates to cells of the heart and cardiovascular system, these changes can lead to heart attacks, strokes, and kidney failure. Endocrine cells genetic shaping can lead to diabetes and metabolic syndrome. . . . This environmental shaping of the gene is well confirmed and is also recognized to be transmissible at least to the fourth generation of one’s descendants and beyond. That means that any environmental hardship experienced by your ancestors and causing this genetic environmental shaping could possibly, and is probably, transferred down to you, their descendant, and likewise your progeny, for generations. This is The Transgenerational Epigenetic Effect (TGEE).”

EPIGENETICS AND NEUROSCIENCE

The limbic system of the brain is a group of structures that include the amygdala, hypothalamus, the thalamus, and the hippocampus. These brain regions work in concert with one another in the processing of information gathered through the sense organs which are stored as memories which later are processed as the evolving human begins to interact with the environment. Dr. Nave continues,

“Liken the limbic system of the brain to the central processor, or hardware, of a computer (human beings are the computer), and the genes of the cells which make up this region, to the software which operates the computer. The epigenome would then be the software programmer, the brain’s Information Technology Specialist, that writes, or rewrites, the genetic program that controls the operation of the cells of the limbic system. Under certain environmental conditions, the epigenome programs or ‘reprograms’ the genetics of the cells of the limbic system which can then lead to pathologic genetic expression, or function, of the cells of this region. The end result of this altered genetic expression is mental illness and/or pathologic social behavior. . . . The limbic system, in its most fundamental definition, is the center of all human thought, emotion, behavior, learning and, when present, psychosocial pathology. . . “

The epigenome possesses within it coding, or programming, that is inherited from a person’s ancestors. Once an environmental stress acts upon the epigene of a person the epigene can be changed permanently. Thereby, epigenetic changes that cause disease states [or mental pathologies] can and will be passed onto an impacted persons’ offspring. The children of a person carrying epigenetic markers for disease [or mental pathologies] will then be susceptible to said disease if exposed to the environmental stressors that can initiate epigenetic activation of the gene. We see this expressed in experiments with mice subjected to electroshocks when they attempt to escape their cage through an open door. Eventually, the mice, fearing harm, stop attempting to leave through the open door. What’s interesting is that their offspring who themselves have never been subjected to the electroshock, will also not try to leave through the open door. Hence a pathology or behavior was epigenetically imprinted and expressed by the offspring.

Additionally, according to neuroscience, when faced with a threat—real or imagined, physical or emotional—the most primitive parts of the brain go into action to determine if the threat is a credible one. If it finds that yes, the threat is real, it will then go into survival mode and determine if you should stay and fight or run away—whichever one will most likely result in survival.

After surviving the trauma of the middle passage, for example, the most primitive parts of a brain are already triggered to enter the most extreme fight or flight condition which are both ACUTE and CHRONIC. Already in a state of physical, emotional and spiritual abuse and degradation,the constant threat of violence made fighting and escaping both unsuitable choices for survival for most African peoples, especially those who came from societies with classes [unlike Balantas] where subservience to a Chief or King was already epigenetically encoded behavior. For most of the African people disembarking from middle passage ships, submission and obedience proved to be the only choice likely to result in survival. Over time these tactics become imprinted on their brains. They become the brain’s go-to fix when it feels threatened. This then became a pattern. One didn’t have to think about these tactics. They just become part of one’s comfort zone and one’s automatic response to feeling unsafe or uncomfortable.

These types of tactics are referred to as familiarity heuristic. In other words, the brain reverts to what it’s familiar with when faced with a threat. Remember, the brain’s job is to keep you safe and make sure you survive. What the brain considers safe is what is familiar. After all, what you’ve done to this point has kept you alive. You’ve survived so far, so as far as your brain is concerned, what it’s done to date to keep you safe has worked. For the Balanta, the familiarity heuristic is to escape to remote places, grow one’s own food, defend one’s own territory, and engage in second strike actions against foreign invaders. As we will see, this Balanta familirarity heuristic led to Balanta escaping foreign domination by establishing the Republic of Palmares in 1595 and leading the Republic of New Afrika in 2023.

While TGEE is often used to explain the negative effects of the environment, and in this case, the chattel enslavement environment, TGEE can also be used to explain positive effects of the environment. Following the early descriptions of the Balanta and the later work by Amiclar Cabral and Walter Rodney, Siphiwe Baleka has shown in his three-volume history of the Balanta that

“. . . the origin of our family’s migration from the land of Ta-Nihisi just prior to the conquest of Menes and the unification of Ta-Nihisi and Ta-Meri to form the first Kemetic (Egyptian) dynasty around 3100 B.C.. . . . From Ta-Nihisi we migrated along the route from Darb el-Arbeen to Wadai and further west to Lake Chad. Somehow, our Balanta ancestors avoided war, capture and enslavement by migrating west to escape the invasion from the east and keeping to the southern Sahel corridor to avoid the invasion from the north. In this way we maintained our freedom for over 4,300 years and did not violate our Great Belief against successive persecutions from the Mesinu (followers of Horus at Edfu), Theme (Libyans), the Shashu and Habiru (Hyksos), Soninke of Wagadu (Ghana), Tuareg (Berbers), Almoravids in Wagadu (Ghana), Keita Clan (Mali), the Sunni Dynasty (Songhai), the Askia dynasty (Songhai), the Moors, fulbe (Fulani coming from the West), and lastly, by the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Bijago, Papel and the Manding of the Kaabu Kingdom. Because we did not develop hierarchical state societies nor written records, much of that 4,300-year history also remains shrouded in mystery.”

Shrouded in mystery, yes, but encoded epigenetically!

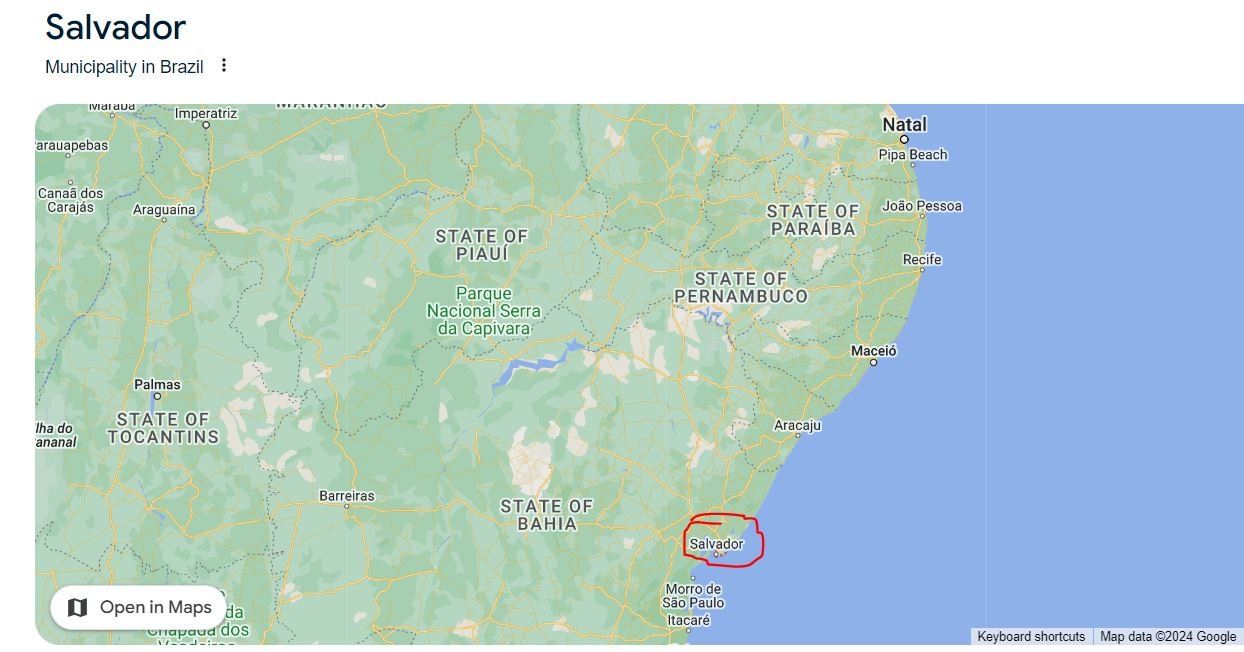

I am proposing that this multi-millennial history of Balanta migration, resistance and freedom was triggered by the environmental conditions of enslavement by the Portuguese and resulted in pathologically-produced liberation movements by the enslaved Balanta first in Portugal in the Confraternity of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men (1496), then in the communities of Salvador (1549) and Jaguaripe (Santidade movement in the late 1500’s)) in Brazil, then in the establishment of the Republic of Palmares (1595), and much later in the civil rights movement and New Afrikan Independence Movement in the United States (1960s) up until the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika today and exposes the distortion that only benign cultural carryovers such as dancing and cooking were transferred by the Africans from their homelands to the Americas, but so too did political and military cultural practices.

Connecting the Balanta Through Historic Liberation Movement in the Americas

Outline

Balanta pursued Reparations through second-strike actions during their resistance against the Mali Empire.

When the Mandinka of the Mali empire raided the Balanta villages, the Balanta would flee, leaving their cattle behind. Later, they would go and retrieve their cattle. This is called “Reparations”, not theft.

2. People from territory in Guinea Bissau, including Balanta, were kidnapped and captured as prisoners of war and trafficked to Portugal and enslaved in the 1450’s.

From the perspective of the Europeans, all the Papal bulls from 1452 to 1493 gave both Spain and Portugal the legal right to capture and enslave Africans at will. When the Portuguese returned from their sixth expedition to Guinea, they brought with them about 653 enslaved, some of which included the Balanta, known for their fierce love of freedom and resistance to foreign domination.

3. People from territory in Guinea Bissau, including the Balanta, formed a brotherhood in Portugal in 1496 for the purpose of liberation.

The Confraternity of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men - was created in Lisbon at the Monastery of Sao Domingos on 14 July 1496, forty years after the Portuguese had arrived in the region of modern Guinea-Bissau. By 1526 the confraternities had been granted the right, via their compromisso or constitution, to liberate their members from slavery or buy them from captivity.

4. People from territory in Guinea Bissau, including the Balanta were sent to Brazil from 1500 - 1600.

From 1570 - 1600, an annual average of 3,000 African captives were shipped largely from Quinara, an important Biafada kingdom in pre-colonial Guinea-Bissau situated between the Geba and Rio Grande de Buba rivers, and about half of the slaves were sent to Brazil. From 1600-1650, about 4,000 slaves from the Upper Guinea coast were exported annually to Brazil and elsewhere (about 200,000 for this period). Balanta had the lowest number of captured prisoners of war because of their effective resistance.

5. People from territory in Guinea Bissau, including the Balanta, came as free Africans to Salvador, Brazil in 1549 and developed an extensive trans-Atlantic trading and communications network.

From its inception as a city in 1549, Salvador (Brazil) served as a link to Pernambuco, Paraiba and Sergipe in the north of the country and the isles, Porto Seguro, Espirito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, Sao Vicente and Buenos Aires in Argentina to the south. Ships brought “free Africans from the region of modern Guinea Bissau, Cacheu, who were hired to work as carpenters.”

6. People from territory in Guinea Bissau, including the Balanta, started the Santidade movement against the Portuguese in the late 1500s.

In the late sixteenth century Guineans, probably led by Balanta, helped form the Santidade movement in Jaguaripe (Bahia, Brazil). It resisted Portuguese ideology that marginalized both Indigenous and Africans in Bahia.

7. People from territory in Guinea Bissau, including the Balanta, started the Quilombo of Palmares in 1607.

The community at Palmares (Brazil) started when forty Guinean men, former enslaved people from Pernambuco and some of them most likely freedom-loving and fiercely resistant Balanta, left for Palmares and formed a republic there that existed as a safe haven from 1607 to 1695. It is unlikely that it was the Beafada and Brame Guineas, or any other peoples from the same region, that led this movement since they were dependent on Balanta for farming and did not have the heritage of resistance and decentralized social structure like the Balanta.

8. Palmares inspired Imari Obadele, principal founder and former President of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika.

Imari Obadele wrote ten pages on the Republic of Palmares in his Doctoral dissertation, NEW AFRICAN STATE-BUILDING IN NORTH AMERICA: A Study of Reaction Under the Stress of Conquest

9. The Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika is led today by two Balanta descendants.

Balanta descendant Krystal Muhammed is the current President of the PGRNA while Balanta descendant Siphiwe Baleka serves as its Minister of Foreign Affairs. Siphiwe Baleka also created the Decade of Return Initiative in Guinea Bissau and is the first Balanta to return and receive citizenship in his ancestral homeland, making him the first Dual Citizen of the Republic of New Afrika and the Republic of Guinea Bissau.

EARLY DOCUMENTATION OF BALANTAS

Table I: Earliest Evidence

Table II: Upper Guinean Origin of Slaves in the Americas 1560-1600

Early description of Balanta people and communities as “cruel”, “savage”, and “barbarous”

The first documented Balanta to be trafficked and enslaved is recorded in 1510. From the 1570’s - 1600, an annual average of 3,000 African captives were shipped largely from Guinala (or Quinara, an important Biafada kingdom in pre-colonial Guinea-Bissau situated between the Geba and Rio Grande de Buba rivers) in Guinea-Bissau by the lancados and Tangomaos; about half of the slaves are sent to Brazil. From 1600-1650, about 4,000 slaves from Upper Guinea coast were exported annually to Brazil and elsewhere (about 200,000 for this period).

The low number of documented enslaved Balantas (7) as compared to others in the same region such as Biafara (Beafada 167) and Brame (Buramos 212) from 1569 to 1577 is likely a testament to the Balantas effective resistance to foreign domination.

In Planting Rice and Harvesting Slaves: Transformations along the Guinea-Bissau Coast, 1400-1900, Walter Hawthorne writes,

“By forging ties of kinship with local women and through them local communities, Portuguese and Luso African merchants linked local systems of production with a broad Atlantic economy and orchestrated the shipment of slaves from Guinea Bissau. . . . It is partly due to the success of Portuguese and Luso African brokers that the volume of the slave trade from Guinea-Bissau’s shores grew, particularly in the years after Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the New World in 1492. . . . Diversity and unpredicatablity fueled the wars and encouraged the raids that produced thousands of captives. On this Rio de Sao Domingos [a small tributary of the Cacheu] Almada wrote in the late sixteenth century, ‘there are more slaves than in all the rest of Guinea since they take them [from] these nations - Banhuns, Buramos, Cassangas, Jabundos, Falupos, Arriatas and Balantas.’ Each of these groups was located within the ria coastline and close to the frontier of the powerful and expanding interior state of Kaabu. . . . In the early sixteenth century, the Rio Cacheu was situated on the frontier of the Casa Mansa (or Casamance) kingdom and possessed a mixed population of Cassanga, Mandinka Floup, Balanta, Brame and Banyun. . . . By about the mid-sixteenth century, the Cassanga king had become wealthy by directing military and judicial institutions toward producing slaves who were sold to Atlantic merchants. Andre Alvares de Almada noted that, with ‘spears, arrows, shield, knives and short swords, as well as thick clubs ‘of up to three hand-spans long,’ Casa Mansa’s armies attacked Banyun, Brame, and Balanta communities between and around the Rio Casamance and Rio Cacheu, making slaves of many people. . . . In the closing years of the century, Cacheu replaced Sao Domingos as the most important entrepot on the Rio Cacheu. . . . About 125 kilometers upriver from Cacheu, Farim was also an important port on the Cacheu. Farim sat at the ria coastline’s edge and attracted a great number of Mandinka merchants, who dubbed the town Tubabodaga, or ‘White Man’s Village.’ There lancados met with Mande-speaking traders, most of whom were from Kaabu. . . . This was a period of expansion of both the Kaabu empire and the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves taken in Kaabu wars were sold to lancados at Farim and then shipped west to Cacheu, where they were put aboard vessels bound for the Cape Verde Islands and points beyond. . . . As the violence connected with the Atlantic slave trade proliferated on the coast at the end of the sixteenth and start of the seventeenth century, many Balanta found living in dispersed morancas to be very dangerous. Hence morancas began to ‘concentrate’ into defensive tabancas, many of which were surrounded by large stockades. . . . For example, Adelino Bidenga Sanha stated, ‘the tabanca grew rapidly because of the wars of the Fula. For this, Balanta liked to agglomerate so as to make groups for war or to counter attacks of Fula and Mandinka who at times attacked Balanta. After this Balanta began to marry among themselves. This contributed to the enlargement of this and other tabancas. . . . By the seventeenth century, Guinea Bissau’s ports of Cacheu and Bissau had emerged as the most important commercial centers on the Upper Guinea Coast. The slaves departing from these points found themselves forced to labor beside Africans from elsewhere on the continent on plantations, in mines, and in cities across the New World.’”

Wlater Rodney continues in Upper Guinea and the Significance of the Origins of Africans Enslaved in the New World,

“Portuguese slave traders regarded the river Cacheu as a slaver’s paradise, for within the narrow compass of that river basin, they encountered five people’s - Djola, Papel, Banhun, Casanga and Balanta each of whom was divided into several political units. Neither the Djola nor the Balanta took any active part in the slave trade, but they were nevertheless to be found among slave cargoes because they were exposed to attacks and man stealing by their neighbors. The Bijago who resided in the islands off the Cacheu and Geba estuaries, were particularly noted for their piratical activities, and steadily supplied the Portuguese with Djola, Papel, Balanta, Beafada and Nalu captives. Bijago hostilities were at their height at the turn of the seventeenth century, when the raids of their formidable war canoes forced the three Beafada rulers of Rio Grande de Buba to appeal to the king of Portugal and the Pope for protection, offering in turn to embrace Christianity. Long after this peak period, the inhabitants of the tiny Bijago islands were still supplying over 400 captives per year, all taken from the coastal strip between the Cacheu and the Cacine. . . . The most significant partnership was between the Europeans and the Mandinga, among the latter of whom were the principal agents of the trans-atlantic slave trade in Upper Guinea.”

The earliest account of the Balantas by name in written records is recorded by Valentim Fernandes, Descripcam, in 1506: “There was very little stratification in Balanta society. Everyone worked in the fields, with no ruling class or families managing to exclude themselves from daily labor.” Andre Alvares Almada (Trato breve dos rios de Guine, trans. P.E.H. Hair -) wrote in 1594, “The Creek of the Balantas penetrates inland at the furthest point of the land of the Buramos [Brame]. The Balantas are fairly savage blacks.” In 1615, Manuel Alvares commented, ‘They [Balantas] have no principle king. Whoever has more power is king, and every quarter of a league there are many of this kind.’ In 1617 more than 2,000 African captives were shipped from Cacheu. In 1627, Alonso de Sandoval wrote that Balanta were ‘a cruel people, [a] race without a king.’

Describing the Balanta as farmers and cattle herders with an organized, decentralized egalitarian political system

The terms “cruel” and “savage” used to describe Balanta can easily be qualified as political terms used to demonize them for their fierce and effective resistance to domination and enslavement. According to Amilcar Cabral, “because of their type of society, a horizontal (level) society, but of free men, who want to be free, who do not have oppression at the top, except the oppression of the Portuguese. The Balanta is his own man.” Walter Rodney agrees. During this period from the 1570’s to 1776, Rodney writes in A History of The Upper Guinea Coast 1545 to 1800,

“Indeed, some tribes displayed chronic hostility towards the Europeans; The Djolas were in this latter category. . . . Another group, the Balantas, were so hostile that the belief was widespread among the Europeans on the coast that the Balantas killed all white men that they caught.“

According to John Horhn’s They Had No King: Ella Baker and the Politics of Decentralized Organization Among African Descended Populations,

“Furthermore, the Balanta were extremely mistrusting of outsiders not from their own lineage or tabancas. This was true even when applied to members of their own ethnic group and resulted in a culture that held loyalty to the tabancas above all else. Therefore, it was impossible for outside forces to gain influence over Balanta culture without direct conquest and the commitment of military resources. The fact that the Balanta possessed very little material culture and existed in dispersed settlement patterns would have discouraged the notion of any such conquest.”

Walter Hawthorne also writes in Strategies of the Decentralized,

"One of the most important strategies was abandoning places that were easily accessible and therefore vulnerable to attack. . . . As interior states began to form before the fifteenth century and to harvest captives for sale to Atlantic merchants in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, many groups saw migration as the best way to avoid enslavement and subjutgation. . . . One strategy was to seize captives and to ransom them back to the villages from which they had come. Myriad Balanta communities that were reluctant to have direct trade contacts with Europeans pursued this strategy. For example, in 1927, Alberto Gomes Pimentel wrote that when the Balanta seized people they were often held until ‘relatives’ paid some price for the freedom of their kin. Cattle, he said, were often demanded as payment, but other items were also requested. Oral narratives also give us a picture of what might have been a typical transaction. Speaking of Balanta raids, one informant said that ‘prisoners were tied to the branch or trunk of a cabeceira tree for some time. Those of strength communicated to the families of the prisoners that they should pay a ransom for the prisoners if they were to be freed.’ Others spoke of the exchange of captives for a ransom. Through ransoming, some Balanta communities avoided entry into the regional trade in slaves but managed to increase the wealth of their communities and to gain valuable items such as iron, that they needed for defense against slave raiders.”

In Planting Rice and Harvesting Slaves: Transformations along the Guinea-Bissau Coast, 1400-1900, Walter Hawthorne writes,

“Faced with the proliferation of violence associated with slave raids, Balanta living in dispersed morancas or households, began concentrating into tabancas in secluded areas near coastal rivers where they could better defend themselves. . . . As late as 1732, European sailors were loath to venture up the Rio Geba for fear of coming in contact with Balanta age-grade warriors. . . . Portuguese and French officials on the coast left many complaints about Balanta stealing cattle at the same time they were capturing people. ‘They are all great thieves,’ Manuel Alvares noted in the early seventeenth century, ‘and they tunnel their way into compounds to steal the cattle. They excel at making assaults . . . taking everything they can find and capturing as many persons as possible.’. . . Spanish Capuchins specifically mentioned that Balanta ‘play a certain instrument that they call in their language bombolon’ to ‘announce the attack.’ . . .

Oral narratives are not the only places we can find evidence . . . Occupying lands next to some of the most important interregional trade routes (the Rio Geba, Rio Cacheu, and Rio Mansoa), Balanta staged frequent attacks on merchant vessels. During such assaults, Balanta seized passengers to sell back to the communities from which they had come, ‘to black neighbors,’ who took them to Bissau or Cacheu . . .

If Balanta staged raids on villages and merchant vessels, what did they do with those they seized? Like people in other parts of Africa, Balanta exercised several options with captives. They sold, ransomed, killed, and retained them, and they did these things for reasons inexorably linked to the logic of Balanta communities.

Balanta typically divided captives into two groups: whites and Africans. Whites were often killed, dismembered, and displayed as trophies by bold young men who returned to their villages with members of their age grades to celebrate a victory. Capuchin observers noted this behavior:

‘The Balanta only hold the blacks to sell them, but as for the whites that they seize, unfailingly, they kill them. Immediately, they cut them to pieces, and they put them as trophies on the points of spears, and they go about making a display of them through the villages as a show of their valor, and he who has murdered some white is greatly esteemed.’

Barbot also left a description of Balanta killing white merchants. The inhabitants of the banks of the Rio Geba, he wrote, ‘are more wild and cruel to strangers than themselves; for they will scarce release a white man upon any conditions whatsoever, but will sooner or later murder, and perhaps devour them.’ La Courbe told a similar story. Balanta, he warned, ‘are great thieves. They pillage whites and blacks indiscriminately whenever they encounter them either on land or at sea. They have large canoes and they will strip you of everything if you do not encounter them well armed. When they capture blacks, they sell them to others, with whites they just kill them.’ . . .

In part, the Balanta and other coastal groups resisted enslavement by exploiting the advantages offered by the region in which they lived. Put simply, the coast offered more defenses and opportunities for counterattack against slave-raiding armies and other enemies than did the savanna-woodland interior. In the early twentieth century, Portuguese administrator Alberto Gomes Pimentel explained how the Balanta utilized the natural protection of mangrove-covered areas – terrafe in Guinean creole – when they were confronted with an attack from a well-organized and well-armed enemy seeking captives or booty: ‘Armed with guns and large swords, the Balanta, who did not generally employ any resistance on these occasions. . . . pretended to flee (it was their tactic), suffering a withdrawal and going to hide in the ‘terrafe’ on the margins on the rivers and lagoons, spreading out in the flats some distance so as not to be shot by their enemies. The attackers. . . . then began to return for their lands with all of the spoils of war’. Organizing rapidly and allying themselves with others in the area, the Balanta typically followed their enemies through the densely forested coastal region. At times, the Balanta waited until their attackers had almost reached their homelands before giving ‘a few shots and making considerable noise so as to cause a panic.’ The Balanta then engaged their enemies in combat, ‘many times corpo a corpo’. . . .

Having assembled in what the Capuchins called ‘a great number,’ Balanta warriors struck their stranded victims quickly and with overwhelming force. ‘Upon approaching a boat,’ the Capuchins said, ‘they attack with fury, they kill, rob, capture and make off with everything.’ Such attacks happened with a great deal of regularity and struck fear in the hearts of merchants and missionaries alike. Others also commented on the frequency of Balanta raids on river vessels. On March 24, 1694, Bispo Portuense feared that he would fall victim to the Balanta when his boat, guided by grumetes, ran aground on a sandbar, probably on the Canal do Impernal, ‘very close to the territory of those barbarians.’ . . . .

Faced with an impediment to the flow of trade to their ports, the Portuguese tried to bring an end to Balanta raids. But they were outclassed militarily by skilled Balanta age-grade fighters.

Portuguese adjutant Amaro Rodrigues and his crew certainly discovered this. In 1696, he and a group of fourteen soldiers from a Portuguese post on Bissau anchored their craft somewhere near a Balanta village close to where Bissau’s Captain Jose Pinheiro had ordered the men to stage an attack. However, the Portuguese strategy was ill conceived. A sizable group of Balanta struck a blow against the crew before they had even left their boat. The Balanta killed Rodrigues and two Portuguese soldiers and took twelve people captive.”

However, these same “savages” and “barbarous” people were also the most organized farmers and cattle herders with a collective system of land ownership and government as first observed by Valentim Fernandes in 1506. Rodney writes in A History of The Upper Guinea Coast 1545 to 1800,

“The earliest European reports disclose that the Balantas had a multiplicity of petty settlements consisting of family lineages (Fernandes, 80)... The Balantas had quantities of prime yams…. The best farmers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries - the Balantas, the Banhuns, and the Djolas- all had cattle and goats …. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Andre Dornelas pointed out that Balanta territory was free from heavy vegetation. It was these very Balantas who reared the most livestock in the area, and it was they who provided supplies of foodstuffs for their neighbors…. That peoples who were far superior producers of food than the Mande and Fula are consistently dubbed ‘Primitives’ is due solely to the contention that they did not erect a superstructure of states.... It is only the Balantas who can be cited as lacking the institution of kingship. At any rate there seemed to have been little or no differentiation within Balanta society on the basis of who held property, authority and coercive power. Some sources affirmed that the Balantas had no kings, while an early sixteenth-century statement that the Balanta ‘kings’ were no different from their subjects must be taken as referring simply to the heads of the village and family settlements as in the case of the Balantas, the family is the sole effective social and political unit. . . .The distribution of goods, to take a very important facet of social activity, was extremely well organized on an inter-tribal basis in the Geba-Casamance area, and one of the groups primarily concerned in this were the Balantas, who are often cited as the most typical example of the inhibited Primitives. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Portuguese realized that the Balantas were the chief agriculturalists and the suppliers of food to the neighboring peoples. The Beafadas and Papels were heavily dependent on Balanta produce, and in return, owing to the Balanta refusal to trade with the Europeans, goods of European origin reached them via the Beafadas and the Papels. The Balantas did not allow foreigners in their midst, but they were always present in the numerous markets held in the territory of their neighbors. . . . Among the Balantas, who are to be classed as a ‘stateless society’, the system of land tenure is different. The Balantas are all small landowners, working their lands on the principle of voluntary reciprocal labour.”

Amilcar Cabral in an excerpt from Part 1 The Weapon of Theory, Party Principles and Political Practice adds,

“The Balanta have what is called a horizontal society, meaning that they do not have classes one above the other. The Balanta do not have great chiefs; it was the Portuguese who made chiefs for them. Each family, each compound is autonomous and if there is any difficulty, it is a council of elders which settles it. There is no State, no authority which rules everybody. . . . Each one rules in his own house and there is understanding among them. They join together to work in the fields, etc. and there is not much talk. . . . Balanta society is like this: the more land you work, the richer you are, but the wealth is not to be hoarded, it is to be spent, for one individual cannot be much more than another. That is the principle of Balanta society. . . . As we have said, the Fula society, for example, or the Manjaco society are societies which have classes from the bottom to the top. With the Balanta it is not like that: anyone who holds his head very high is not respected any more, already wants to become a white man, etc. For example, if someone has grown a great deal of rice, he must hold a great feast, to use it up. Whereas the Fula and Manjaco have other rules, with some higher than others. This means that the Manjaco and Fula have what are called vertical societies. At the top there is the chief, then follow the religious leaders, the important religious figures, who with the chiefs form a class. Then come others of various professions (cobblers, blacksmiths, goldsmiths) who, in any society, do not have equal rights with those at the top. By tradition, anyone who was a goldsmith was even ashamed of it - all the more if he were a ‘griot’ (minstrel). So, we have a series of professions in a hierarchy, in a ladder, one below the other. The blacksmith is not the same as the cobbler, the cobbler is not the same as the goldsmith, etc.; each one has his distinct profession. Then come the great mass of folk who till the ground. They till to eat and live, they till the ground for the chiefs, according to custom. This is Fula and Manjaco society, with all the theories this implies such as that a given chief is linked to God. Among the Manjaco, for example, if someone is a tiller, he cannot till the ground without the chief’s order, for the chief carries the word of God to him. Everyone is free to believe what he wishes. But why is the whole cycle created? So that those who are on top can maintain the certainty that those who are below will not rise up against them. . . . In the societies with a horizontal structure, like the Balanta society, for example, the distribution of cultural levels is more or less uniform, variations being linked solely to individual characteristics and to age groups. In the societies with a vertical structure, like that of the Fula for example, there are important variations from the top to the bottom of the social pyramid. This shows once more the close connection between the cultural factor and the economic factor, and also explains the difference in the overall or sectoral behavior of these two ethnic groups towards the liberation movement. . . . In this bush society, a great number of Balanta adhered to the struggle, and this is not by accident, nor is it because Balanta are better than others. It is because of their type of society, a horizontal (level) society, but of free men, who want to be free, who do not have oppression at the top, except the oppression of the Portuguese. The Balanta is his own man. . . . “

Additionally, In Planting Rice and Harvesting Slaves: Transformations along the Guinea-Bissau Coast, 1400-1900, Walter Hawthorne writes,

“Like most in the coastal reaches of Guinea-Bissau, Balanta society was politically decentralized. In such societies, the village or confederation of villages was the largest political unit. Though a range of positions of authority often existed within villages and confederations, no one person or group claimed prerogatives over the legitimate use of coercive force. In face-to-face meetings involving many people, representatives from multiple households sat as councils threshing out decisions affecting the whole. At times, particularly influential people emerged, sometimes wielding more power than others and becoming ‘big men’ or ‘chiefs’. However, no ascriptive authority positions existed. Consensus was king. Whereas state-based systems concentrated power narrowly in a single ruler or small group of power brokers, in decentralized systems, power was more diffuse. Decentralized systems relied on unofficial leaders, but they lacked rulers. . . .

[B]alanta, like many people living in decentralized societies, have not recorded their history on paper, and have few formalized and structured oral narratives. . . . Balanta frequently exchanged ideas and material goods with people with whom they came into contact. Such exchanges often took place in regional markets where Balanta yam, salt, and cattle producers met and mingled with merchants, some of whom offered expensive items not found locally but carried from other ecological zones. Competing for these items with other coastal dwellers, most of whom produced the same mix of goods, Balanta purchasing power was weak. Their ability to accumulate long-distance trade items, particularly iron, which was valuable for reinforcing agricultural implements needed in the production of particular crops, was very limited.

Regularly meeting with others to trade, Balanta just as frequently resisted attempts by area groups, most importantly Mandinka from the powerful state of Kaaba, to dominate them politically. The decentralized nature of Balanta political and social structures and the physical environment that they inhabited facilitated this defense. Balanta, then, never became, as some scholars argued, ‘layers within the large section of the population which labored for the benefit of the [Mandinka] nobility.’ They struggled, often successfully, to maintain the independence of their households. . . . Resisters, then, refused to recognize Mandinka authority, uprooting their communities and taking refuge on the coast.”

Thus, from the 1500s to the 1750s, the Balanta people were exceptional farmers and cattle herders that had a heritage of fleeing foreigners attempting to dominate them and successfully defending and maintaining the independence of their households, unlike the other peoples living in the territory of Guinea. As we will see, Balanta would carry-over these things to Brazil and lay the foundation for the establishment of the Republic of Palmares (1607-1695). Likewise, Portugal would carry-over its dehumanization from Guinea to Brazil. However, on this point of demonizing the Balanta as “savages” and “barbarous”, consider:

President of the Republic of New Afrika, Imari Obadele writes in Revolution and Nation Building: Strategy for Building the Black Nation in America (1970):

“All of you who are New Africans have probably heard people ask what kind of political system and economic system will you have? They are attempting to get you to answer in terms of capitalism, socialism, communism, totalitarianism, democracy. What they don’t understand, and what you must understand, is that all of those terms are too limited to describe the African experience and what you as a New African are attempting to build.

Now why is that? One reason, of course, is that these terms were, for the most part, developed by Europeans in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries as they strove to make the world in which they lived understandable to them. The special meanings which we today associate with the terms communism, socialism, and capitalism were developed by Marx and Engels and, later, by Lenin, because they needed a theory - a complete world-view - which they felt to be scientific, to interpret the world and explain their revolution and help provide a method of action for the revolution they were dealing with. But the meanings came out of the European experience.

At the time they wrote, the theories of Darwin were beginning to enjoy a certain popularity. Today we take the theory of the evolution of man more or less for granted, but in those days they didn’t. To the scientists of that time it was a very exciting theory. Once Darwin, who was a biologist, had been able to demonstrate that man was a product of development through physical stages - that is to say, from Pithecanthropus Erectus (a very ape-like type), through Neanderthal man (a less ape-like type) to Homo Sapiens (modern man), Marx and other social scientists of his day, having looked at this type of progress, thought that it might be possible to look at the kinds of societies in which men live, the kinds of governments they have, and explain all this by use of a similar theory of evolution, of progress. As a result, they said that human society develops by passing through three main stages: savagery to barbarism to civilization. That was the game they played in those days. And they said, naturally, that white people represented the civilized world and everybody else was in a state either of barbarism or savagery.

These so-called social scientists - historians and political scientists - developing their theories in the Nineteenth Century, were writing at a time when the slave trade had barely ended. Remember the Civil War began in 1861 - Darwwin’s ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES had appeared in 1859, and while Marx’s COMMUNIST MANIFESTO had appeared a decade earlier, Marx organized the International Workingman’s Association in 1864 and published the first volume of his DAS KAPITAL in 1867. What Marx and these other writers came heir to, the kind of literature they had to deal with at the time, was literature written by people who tried to justify the slave trade. In other words, it was written by white Europeans who were saying to other white Europeans that Africans were savages, therefore you should conquer them, enslave them, and civilize them. Remember, that was one of the very early excuses for African slavery; they were going to civilize us. And so all fo the books about other societies in the world outside of Europe tended to portray us as living in stages of savagery or barbarism. We NEEDED to be civilized.

Now, this construct - savagery to barbarism to civilization - is just like most of the other ‘rules’ and constructs of a social science: it is merely a hypothesis and not a law. And it is fundamentally untrue. So, too, with the specific progression that Karl Marx tacked onto the savagery-barbarism-civilization construct - the progression from primitive communalism to capitalism to socialism to communism. This was and is an interesting tool for helping us to understand, in some ways, some things that have happened in society and some things that are going on. But it is a hypothesis and not a law. Societies do not, first of all, all conform to the criteria which Marx established for defining primitive communalism.

What these early writers tended to do was to look at African society and say this is primitive communalism because, for instance, the land is held by the tribe. They would then rank African society at the bottom of the scale - of BOTH scales: we would be both savages and primitive communalists. (Occasionally the better studied African societies would be ranked barbarous and feudal - a step higher.) The truth is that most of the African societies to which they made reference were barked by two characteristics not at all primitive. One was a very elaborate theology, cosmology, and religion. The other was a highly organized political system.”

Dehumanization language used to to eliminate Balantas in Brazil

From 1550 to 1690 most Brazilian slaves (prisoners of war) resided on sugar plantations in the northeast provinces of Maranhão, Pernambuco, and Bahia and in the southern province of Rio de Janeiro. Jose Lingna Nafafe writes in Lourenco da Silva Mendonca and the Black Atlantic Abolitionist Movement in the Seventeenth Century,

“The city of Salvador was not a pleasant place for the colonial elite during the years of the royals’ stay, threatened as it was by Indigenous people and the fugitive enslaved Africans. The most important event of the war against the residents was also predicated on the idea that both enslaved Africans and Indigenous Americans joined forces to attack the city. The Indigenous Americans were associated with Africans in Palmares (Guineans, probably Balanta since they established Palmares). . . . The attack on the city was not unilateral, but rather bilateral, with the Africans joining forces with the Natives. The threat from the Indigenous Americans and Africans worried the City Council, who associated it with Palmares . . . . Palmares was equated with the violence that the ‘non-tamed’ or ‘unseasoned - non conquered’ Indigenous people usually carried out on the Portuguese settlements. The Africans of Palmares (Guineans, probably Balanta) were believed to have a collaboration with the Indigenous people against the Portuguese. . . . In Bahia, it was clear that the Indigenous people and the Africans were seen as threats to the interests of the settlers. So, the council’s petition to the king of Portugal or regent was to ask for support, but also for the license to eliminate the Indigenous people from Bahia: ‘if you were to look at evil things that have been caused to the State of Brazil by the Natives, it was not only that they were made captives, but also to decree that they be eliminated once and for all’. As Marques put it, the category of ‘Indigenous’ underwent a profound change; the Indigenous came to be described as ‘barbarous’, giving the conquistadores a right to make a claim that their actions against them were justifiable. The desired elimination of the Indigenous people required a rhetoric that justified it even while the real objective for repressing them was the appropriation of their resources. . . . On 9 September 1672, the City Council of Salvador requested support from the Crown in Lisbon to destroy Palmares.”

Thus, the dehumanizing language and narrative of “savages” and “barbarous” were used on both sides of the Atlantic, to justify warfare and genocide against the Balanta in their homelands and in Palmares.”

KIDNAPPED BALANTAS RESIST PORTUGUESE ENSLAVEMENT

Nafafe continues,

Portugal

“The historical evidence I found has shown that the popes were in favour of and even encouraged slavery. . . . The pope represented the very institution, the Vatican, which had passed bulls to the Iberian kings (of Portugal and Spain), enjoining them to conquer Africans in the name of the Christian God. . . . Several bulls to this effect had been sent to the Portuguese Crown in the fifteenth century. There was the aforementioned bull of 1452 issued by Pope Nicholas V, Dum Diversas. In 1455, Pope Calixtus III confirmed the monopoly over all lands in Africa to King Afonso V of Portugal. On 3 May 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued the Inter Caetera bulls, granting the West Africa region, and also Brazil, to the Portuguese monarchy, and the Americas to Spain. The boundaries between Portugal and Spain were then settled at the Treaty of Tordesillas on 7 June 1494. All the bulls gave both Spain and Portugal the legal right [Note: in their mind] to capture and enslave Africans at will. Munzer stated clearly that when the Portuguese returned from their sixth expedition to Guinea, they brought with them about 653 enslaved, some of whom they sold in Portugal, while others were given as a present to the pope and the remaining were given to other people.” ( pp 372-373)

“Many enslaved Africans were brought to Portugal. Even in the fifteenth century, Jerome Munzer, a German medical doctor who visited Portugal from 26 November to 1 December 1494, claimed that he ‘saw an enormous forge with many ovens, where anchors and columns were made’, and that ‘there were a great many Negroes working near these ovens . . . . Indeed, there were so many Blacks in Lisbon, that he exclaimed: ‘Of how large the number of Negro slaves in Lisbon these days brought out of Ethiopia’. On 26 March 1535, a Flemish priest, Nicholas Clenardo, wrote from Evora to his friend Latimo that:

‘... the slaves swarm in every part. All the work is done by captive Negroes and Moors. . . . I believe that in Lisbon male and female slaves are more than the free Portuguese. It is difficult to find a house where there is not at least one of these female slaves . . . . the wealthier have slaves from both sexes, and there are people who make good profit with the sale of the slaves’ children born in the house.’

Resende, a Portuguese historian and chronicler, was critical of the number of enslaved Africans in Portugal: ‘we bring into this kingdom a growing number of captives and if the Natives go, that is, if it goes this way, they will be more than us, in my opinion.’ By 1550, in Lisbon alone there were 10,000 Africans, constituting 10 percent of the population. By the mid-eighteenth century 15 -17 percent of Lisbon’s population was of African descent, and 800,000 Africans had been brought to the Iberian Peninsula.” (pp.302 - 303)

As we have seen above, Cacheu was the Portugues main commercial port in Guinea where many Balanta were trafficked as prisoners of the war and invasion launched by Pope Nicholas in which Bijago, Papel, Fula and Mandinka from the Kaabu empire, became enemy combatants against the Balanta.

Confraternities

“So there were many Africans living in Portugal before Mendonca reached the country, and among them were both enslaved and free Africans who had gone to Portugal on their own initiative as students, ambassadors, priests and businessmen. These groups constituted the members of the confraternities, the first of which - the Confraternity of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men - was created in Lisbon at the Monastery of Sao Domingos on 14 July 1496, forty years after the Portuguese had arrived in the region of modern Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone and Senegal.” (pp 303-304)

“By 1526 the confraternities had been granted the right, via their compromisso or constitution, to liberate their members from slavery or buy them from captivity. . . . Furthermore, to comprehend the membership of the confraternities, there is a need to recognize the privileges that the constitution awarded them, in terms of belonging, legal rights and their relationship with the political and religious authorities in the lands in which they were situated.

At the center of the confraternities was the legal framework, the compromisso or constitution that allowed the confraternity members to belong to the community of the free, liberated them from slavery and allowed them to engage in business transactions. By virtue of their membership of a confraternity, members were freemen, the act of becoming a member of a confraternity was an act of freedom. By joining confraternities members exercised their right to freedom. The confraternities were clubs for the free, regardless of their status - be they Africans, Indigenous Brazilians, White Europeans, Blacks, male, femal, Jews, Moors - all could be members. The privileges, particularly those around freedom, afforded to the confraternities via the constitution provided the legal framework in which Mendonca was operating . . . . “ (pp 300-302)

“By the seventeenth century there were many confraternities, or Brotherhoods of Black people, in Portugal. According to Gray, they were seen as ‘a respectable alternative to the revolutionary quilombos or settlements formed by slaves,’ which were more militant in outlook. The confraternities were the centres from which enslaved Africans and free Black, whether born or liberated, living in Portugal could voice their concerns about their position in Portuguese society.” (pp 303-304) [Note: the confraternities were like the early NAACP in the United States while the quilomobos were more like the UNIA]

“The Black Brotherhoods, particularly from Spain, Portugal and Brazil . . . urged the pope to take punitive action against the ‘sellers’ and ‘buyers’ of Africans, and to demand that orders be given to the overseas officials in Africa to prohibit the slave trade inthose regions: ‘It suggested that to repair the situation first, the following is to be done: ministers of Guinea are to order that the sale of kidnapped Black Brotherhoods or those taken from the fields with fraud be prohibited.’ The kidnappers were deploying various tactics to acquire slaves, including capturing them from agricultural fields. Kidnappers went to these places knowing that the Africans would be exposed and an easy target for slave-traders. The Blacks’ statement demonstrates the injustice of the slave trade in seeking captives through easy means, rather than through the alleged wars that were believed to be the legal source of the enslaved.” (p. 358)

Santidade in Bahia

“In the late sixteenth century the Santidade movement arose in Jaguaripe (Bahia). This was described by Ronaldo Vainfas as an Indigenous movement or sect created in response to Portuguese violence in the region. As a movement, it was political as well as religious. It resisted Portuguese ideology that marginalized both Indigenous and Africans in Bahia. Vanifas states that: ‘the Santidade movement was looming in plain sight in its haven in Jaguaripe, inciting revolts, setting Bahia on fire’. As a movement its members included fugitive enslaved Africans and White Europeans. Vanifas declares: ‘there is still no shortage of news about the adhesion of Blacks from Guinea, Mamelukes and even White people who converted to Santidade and practiced their ceremonies.’” (p. 247)

Salvador

“From its inception as a city in 1549, Salvador served as a link to Pernambuco, Paraiba and Sergipe in the north of the country and the isles, Porto Seguro, Espirito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, Sao Vicente and Buenos Aires in Argentina to the south. Ships from India, Angola, the Gold Coast, Guinea and Cape Verde, as well as England, France and Portugal all stopped in Salvador to trade, as Dampier, an English merchant reported in the seventeenth century. The city was home to people from many different nations and included traders, enslaved Africans from West Central Africa, Angola, and form elsewhere on the West African Coast, ‘for the most part, in Senegambia and Guinea-Bissau and Sao Tome and Principe (the so-called Guine [Guinea] enslaved people) among its inhabitants. There were free people from Angola, who were there as soldiers, free Africans from the region of modern Guinea Bissau, Cacheu, who were hired to work as carpenters. Many of them were not employed in the sugar plantations, but as domestic workers, street hawkers, cooks and fishermen, while some of the women became wives or mistresses., or transport workers who carried their masters through the streets of Salvador. The nature of their work meant that both enslaved persons and the free constituted a powerful network throughout the city of Salvador and other regions of Brazil.” (pp 214-215).

Palmares

“According to Sebastiao da Rocha Pitta (1660-1738), a Bahian born in Salvador and a historian, the community at Palmares started when forty Guinean men, former enslaved people from Pernambuco, left for Palmares and formed a republic there. Pitta was a contemporary of the Palmares War (1695). His father, Joao Velho Gondim was a captain, although it is not known whether he took part in the conquest of Palmares. What is certain is that Pitta’s account of the events at Palmares is the most contemporary one that we have. According to him, the men living there were formerly enslaved people, but they had not been ill-treated by their owners, which remains a moot point. In other words, these were men who had voluntarily decided to form a republic of their own with other men with a similar vision to live ‘free of any domination’. Pitta saw their community as a robust republic that was not based on Greek principles or ideology, but on their own African ideals, hence an African republic in Brazil. The group at Palmares was a league of friends, family and relatives or macamba who established a community in which to live and engage in business with the local people. [Siphiwe note: this is the very description of Balanta society back in Guinea] Indeed, the word macamba (meaning friends, family, relatives in Kimbundu) would be a more fitting name than mocambo, as there was no sense that the group set itself up as a military encampment, even though it became necessary for them to engage in armed fighting. It would not be far-fetched to suggest that it was the Portuguese who used the term mocambo rather than macamba to describe the community for political reasons and to encourage support and justify their war against it.

Histories of Palmares have so far made no connection between members of Palmares with their homes in Africa and with the Brazilian-born political elites. What is known is that former enslaved Africans inhabited Palmares and formed a community there. . . .

Antonio Luis Coutinho da Camara, the governor of Bahia from 1690 to 1694, and later a viceroy of India, considered it his key mission to destroy the existing mocambo or quilombos in the region. . . . Like Camamu, Palmares was destroyed in 1695 because it posed a constant and very serious threat to the Portuguese authorities economic interests in the region. . . .

Indeed, an examination of the law regarding war captives in Angola, particularly in Mbundu society, throws light on the dynamics of runaway enslaved people in Brazil. As mentioned in Chapter 2, there was amnesty law used in Mbundu society in the seventeenth century and Angolan customary practices were underpinned by three principles: the Principle of Return or the Principle of mucua; the Principle of Safe Haven; and the Principle of Asylum.

First, the Principle of Return or Mucua was based on the law of liberty, and on the ability of captives to exercise their liberty to gain independence, with the protection of the law. In his Kimbundu grammar, published in 1697, the Jesuit Priest Pedro Dias translated the term mucua into Portuguese as abode, which means a place of habitation. Thus the Principle of Return, that is, of returning home, was not simply about having the independence to achieve freedom, but about having the legal resources to free one’s self when there was a legal precedent to achieve it. This legal framework was the original place, a place of citizenship, home - mucua - and guaranteed nbata rinene or ‘a great house’ or community to which an enslaved could return. According to Thiongo, home is a place of being, where we are taught the values of our legal system, philosophy, history, economy and our identity, in other words, who we are. Accordingly, mucua is a site of Mbundu identity, which is not based on the Cartesian philosophy of being cogito ergo sum (‘I think, therefore I Am’), but on the African philosophy ‘I think therefore we are’. Crime was dealt with in this original place. If an accused was found guilty, his or her sentence and punishment were dealt with locally, and the guilty would repair the damage of the crime by either serving the plaintiff or giving gifts to make up any losses.The soba ensured that any punishment was fair for both parties. This legal system has survived in Angola until today.

Second, the Principle of Safe Haven details the amnesty that applies to a fugitive who finds refuge with a powerful lord or a king. The fugitive may feel that legal process had not been followed in events leading to his or her capture or that the legality of his or her capture had not been proven. Seeking amnesty is fundamental to the captive achieving freedom, and amnesty could be sought from a powerful lord, who would use his power to protect the fugitive.

Third, the Principle of Asylum covers cases where the accused could seek to leave his or her community after being found guilty or simply after being accused if there was not enough evidence to support his or her prosecution. The accused might leave his or her original location and move to another province, in which case amnesty would also apply, but she or he could never return to the location where she or he were accused of the crime, particularly in cases of crimes such as murder and witchcraft. Running away in such circumstances is not based on personal whim; there must be protection and a legal network in place to achieve it. IF a fugitive did not know a powerful lord directly, she or he needed to be introduced to one by a representative.

In Brazil, the Principle of Safe Haven and the Principle of Asylum were applied by the runaway enslaved people through the formation of quilombos or macambos, which entailed the use of these principles. Thus, to run away from one’s captivity was not done in a vacuum; one needed a safe haven. The first principle appears to have been used more frequently than the last in Brazil. Antonil noted that enslaved people, once guilty, could run away or commit suicide, but they normally sought reconciliation with the owners by reuniting with them.

Quilombo dos Palmares could not have existed as a safe haven for as long as it did (1607-1695) without some form of legal space allowing for it. I argue that Brazil, in particular Palmares, was not a terra nullis (‘unowned land’) nor was it res nullis (‘unowned things’); it was not a kind of ‘nobody’s land’. On the contrary, it belonged to the Indigenous Brazilians, who befriended Africans in the region. If it were not for their alliance with the Indigenous Brazilians, who allowed Palmares to exist, there would not have been a safe haven for Africans at Palmares. . . .

Palmares was macamba and not mocambo, it became mocambo by necessity. The intention of its forty founding runaway enslaved people was to form a community and not a military camp, and any military side to the community was only meant to be temporary and for a specific purpose. The claim that Palmares was mocambo was made by the Portuguese to justify a ‘just war’ aimed at its destruction. A mocambo was formed for the purpose of war and not as a permanent state. Palmarists did not see themselves as mocambo, but rather as macamba. Palmares might possibly have survived as an independent state in Brazil, however, had it not been for Viera’s interpretation of it and the theologically infused economic/moral case he made against it. . . .

Palmares was a refusal to submit to the Portuguese, a declaration of independence, and a symbol of insubordination. Resistance provided a space for negotiation as it created an absence in the balance of power between Palmares and the Portuguese Crown. Palmare’s resistance to Portugal’s economic interests was only an option because there was no scope for negotiation. The Palmarists opted for a non-negotiable relationship with the Portuguese. Palmares was a rejection and at the same time an inversion of the colonial values around slavery and the treatment of enslaved people as non-human. However, the Palmarists pursued other things in Palmares, exploring resources, power, wealth, control, collection of taxes and protection. The region of Pernambuco provided the Plmarists with alternative ways to pursue the kind of life that they knew best, the African way of life, with the flexibility to adapt to the local Brazilian environment in which they found themselves.” (pp 241-272)

“Quilobos would not have existed if they were not afforded protection from the so-called ‘untamed’ Indigenous people, the “indios Bravos’ also known as ‘Tapuyas Bravos - Pira-Tapuia. . . . There were two particularly fierce groups of Native fighters in the region - the Cupinharoz and Precatiz. These Indigenous Brazilians could have fought against the Africans in Palmares if they wanted, but they never did; at least we do not have documentary sources to suggest that they did. . . . What is interesting is that the so-called untamed Tapuyas never saw Quilombo de Palmares or Africans in general as their enemies. Instead, they turned their attacks on the Portuguese residence in Peauhy and other areas of Pernambuco. Indigenous people and Africans lived together in Caninde. They supported each other in a fight for survival: they worked together in the fields, herding cattle and trading.” (p. 246)

“To understand the logic of running away from captivity in Brazil, I look at the Angolan legislation covering runaway enslaved people and argue that it was deployed against those who took refuge in Quilombo dos Palmares. . . . Palmares was both a political and social space. It was not only a refuge for enslaved fugitives but also a place in which those born free came together and formed a community parallel to that of the Portuguese enslavers. It was an alternative power structure, with a different economic model. At the time, it was viewed as militant, and a menace to the Portuguese establishment in Brazil who attempted to destroy it by force of arms. Brazilian historiography has seen Palmares as an ‘African state’ in Brazil. More recently there are those who view Palmares as a creolised State.

Based on that, I argue that Palmares created its own economy, which provoked the governing authorities in Bahia . . . . (pp )

“Palmaritsts were the new colonizers of Brazil, and if they were afforded freedom, this ‘would be the total destruction of Brazil, since the other blacks knowing that through this means they could be free, each city, each town, each place, each sugar mill, would soon become other Palmares, fleeing and going to the forests with all their stock, that is nothing more than their own body.” (pp 268-269).

Thus, when Nafafe writes, “according to Sebastiao da Rocha Pitta (1660-1738), a Bahian born in Salvador and a historian, the community at Palmares started when forty Guinean men, former enslaved people from Pernambuco, left for Palmares and formed a republic there” there is a great probability that Balanta where included in those forty Guinean men and that their love of freedom was a driving force behind it since it is unlikely that it was the Beafada and Brame Guineas, or any other peoples from the same region, that led this movement since, back in their ancestral homeland, they were dependent on Balanta for farming and did not have the heritage of resistance and decentralized social structure like the Balanta.

BALANTA EXAMPLE OF PALMARES INSPIRES IMARI OBADELE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NEW AFRIKA

In Black Power, Black Lawyer: Memoir of Nkechi Taifa it is stated,

“Ever since our ancestors were snatched from our homeland of Africa, there have always been people who fought back and fashioned resistance movements to regain freedom and independence. Brother Imari [Obadele] taught that it was military forces nurtured in the hills of Santo Domingo that brought independence to Haiti. One-hundred seventy-five years before that, we revolted and established the legendary Palmares Republic, which lasted over 100 years, located in what is now Alagoas, Brazil, bordering Bahia. Even today, there are more people of African descent in that region than there are in the U.S. This maroon state stood as the greatest challenge to European rule in so-called Latin America.

The Quilombos of Palmeres had hundreds of homes, churches, and shops. Its fields were irrigated African-style with streams. It was a structured society that had courts to carry out justice for its thousands of citizens. It was an elected republic of free, united people, living communally and in prosperity. Unlike the colonizer’s sole emphasis on sugar cane for export, in Palmares, maize, beans, potatoes and vegetables were also planted. Ownership of land was collective, a tradition Blacks brought from Africa.

Periodically, the people of Palmares ventured from the hills to rescue others who were enslaved, obtain arms, powder, and tools and also to mete out justice to overseers. Despite military expedition after expedition, the Republic of Palmares remained independent and was not destroyed by the Portuguese until nearly a hundred years later..

After a 42-day siege, many of the warriors flung themselves over a cliff rather than surrender to the Portuguese. The ruler, Ganga Zumbi, was captured and beheaded by the enemy. In a case of sheer terrorism, his head was barbarically displayed ‘to kill the legend of his immortality,’ according to the ‘civilized’ Europeans. For generations, the Republic of Palmares had united many people under an African form of government and culture, and had successfully defended itself from invaders. After each victory, they returned to planting and harvesting abundant crops, and continuing the quest for sovereignty.

It was clear to me that Brother Imari idolized the Palmares model of an independent government and military system, despite it having occurred during the eras of enslavement and colonialism. He emphasized that in the U.S., free communities set up by escaped Africans in Florida, Georgia, and elsewhere in territory claimed by the United States, were also continuously sought out for destruction.

He stated, ‘Every time we ran away, it didn’t matter whether we went away quietly in the night like Harriet Tubman. It didn’t matter if we organized elaborate insurrections like Denmark Vesey. It didn’t matter if we fled to Pennsylvania or New York - they always came after us, with their armed forces, paddy rollers, militia, and dogs.’

‘Why didn’t it matter?’ Brother Imari would stridently quiz.

‘Because the White folk had decided they were going to live here!’ he thundered in response to his own query. ‘Wasn’t gonna be no 100 years of Palmares liberation.’

When Nkechi Taifa wrote that, she was unaware that she was writing about Balanta ancestors!

Imari Obadele Studies Palmares in his Doctoral Thesis

In May 1985, Imari Obadele submitted his thesis, NEW AFRICAN STATE-BUILDING IN NORTH AMERICA: A Study of Reaction Under the Stress of Conquest, to the Temple University Graduate Board in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. In it he writes,

“The greatest achievement in New African state-building during slavery, next to the triumph of Haiti, was the Palmares Republic in Brazil. Like the Kingdom of New Koromanteen, it lasted for more than 100 years.

In Brazil, the war of European conquest against the Amerindian and the New African, with the European - here, the Portuguese - relentlessly seeking unconditional hegemony, was played out as graphically as anywhere. This remarkable, raging passion of the European not to compromise or share power with the Amerindian or New African but to reduce them each utterly, socially and politically, beneath European hegemony was everywhere present in the Americas. The Kingdom of the Koromanteens had checked it, this passion, and the British had spent huge treasure and the lives of many soldiers, over 75 years, trying not to believe what was happening to them. The Haitians had checked this passion in the French. The Palmares republicans too checked it in the Portuguese - but only for a while. For, in Brazil the passion of the Europeans, the Portuguese, for total social and political hegemony over the Amerindians and the New Africans has been, so far, enormously fulfilled. . . .

As I have indicated, persons held as slaves escaped the harsh conditions and humiliations of slavery, often, by establishing or fleeing to the ubiquitous freedom communities in the interior, which lasted virtually until the end of slavery in 1888. The fact is that these communities were populated not only by escaped slaves but also by free persons, black and mulatto, who also left the reach of the Brazilian state because of oppression and humiliation and who, above all, wanted freedom and opportunity. Not all of the emancipated slaves in Brazil possessed the skills needed, for them, to overcome the obstacles imposed on peoples of color, once they were liberated. . . .

The annals of African slavery in the New World contain instances of slaves in North America and in South America who fled from plantations not to set up permanent new communities in the forest but to protest conditions of work and to return on promise of improved conditions (this was in the nature of a labor strike), or who fled simply as a method of gaining a vacation from the plantation routine before returning. Thomas Flory even suggests that some plantation owners in Brazil may have tolerated the existence of nearby quilombos - freedom villages - as a means of maintaining a reserve labor force during the slack seasons without costs to the plantation, since the escaped Africans would grow their own food in the quilombos and might return to the plantation to work during planting and harvesting, much like contract workers.

Whether or not Flory’s speculation is probable, and however un-rare slave labor negotiations may have been, it is certain that many thousands of Africans in the Americas escaped from slavery with the preconceived determination of departing that condition forever. History makes us equally certain that - although this reality is purposely underplayed in the literature, hastily reported, and generally denigrated - thousands of Africans sought not only abstract freedom but the building of states.

The first of the communities which would ultimately become the Palmares Republic was established in northeastern Brazil about 1595. It was known during the governorship of Diogo Botelho (1602-1608), and while the Dutch seized and held the Portuguese town of Recife and its environs, that determined freedom village - or, quilombo - suffered at least two major attacks by the Netherlanders. The last was particularly devastating When, therefore, a major new group of Africans arrived in 1650, the community made the decision to move the settlement deeper into the forest of the Captaincy of Pernambuco, far beyond the white frontier.