“The shift from a domestic civil rights model to an international human rights model will be, for the professional African and Anglo-American communities, in Thomas Kuhn’s words, ‘as if the professional community [is] suddenly transported to another planet where familiar objects are seen in a different light and are joined by unfamiliar ones as well.’”

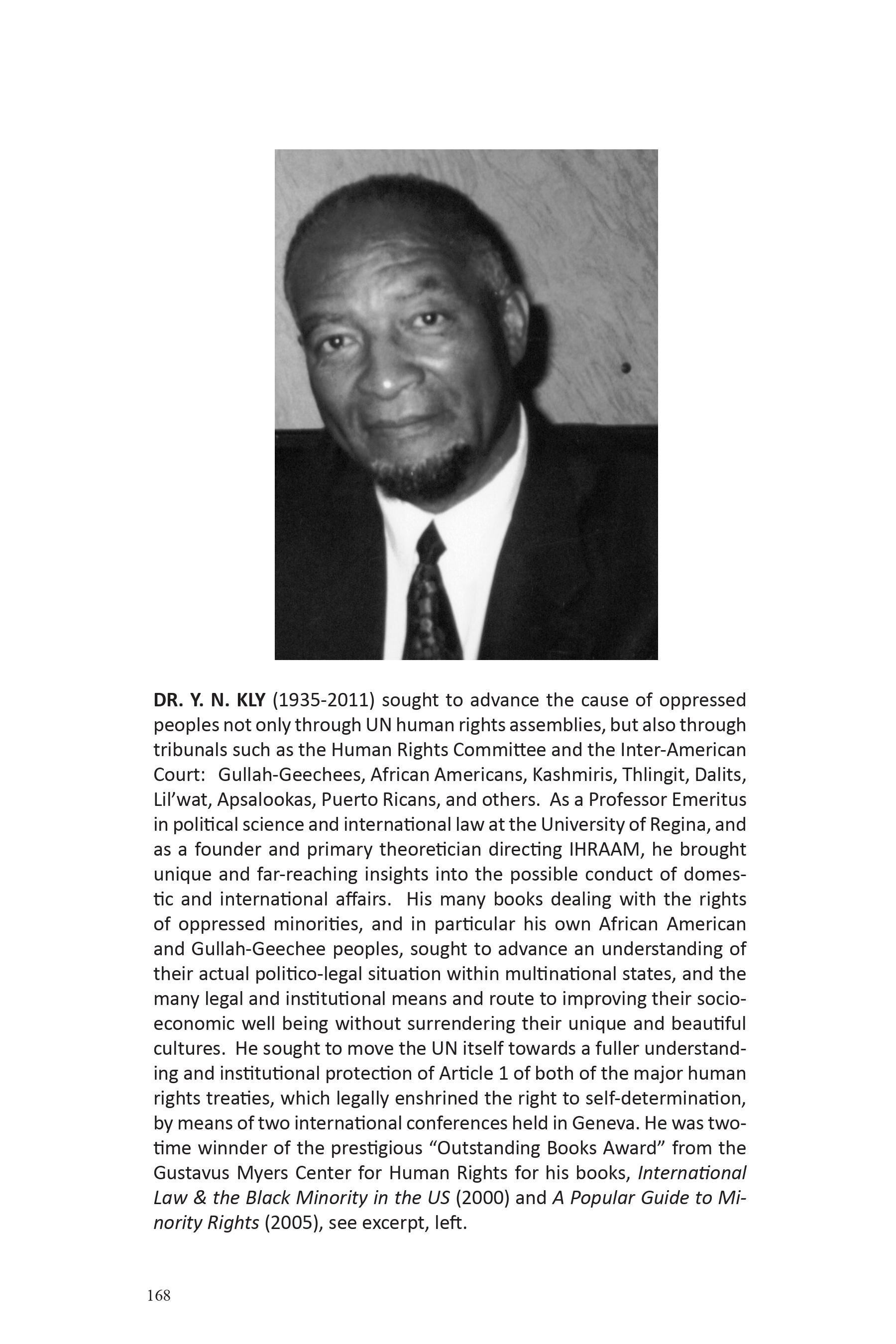

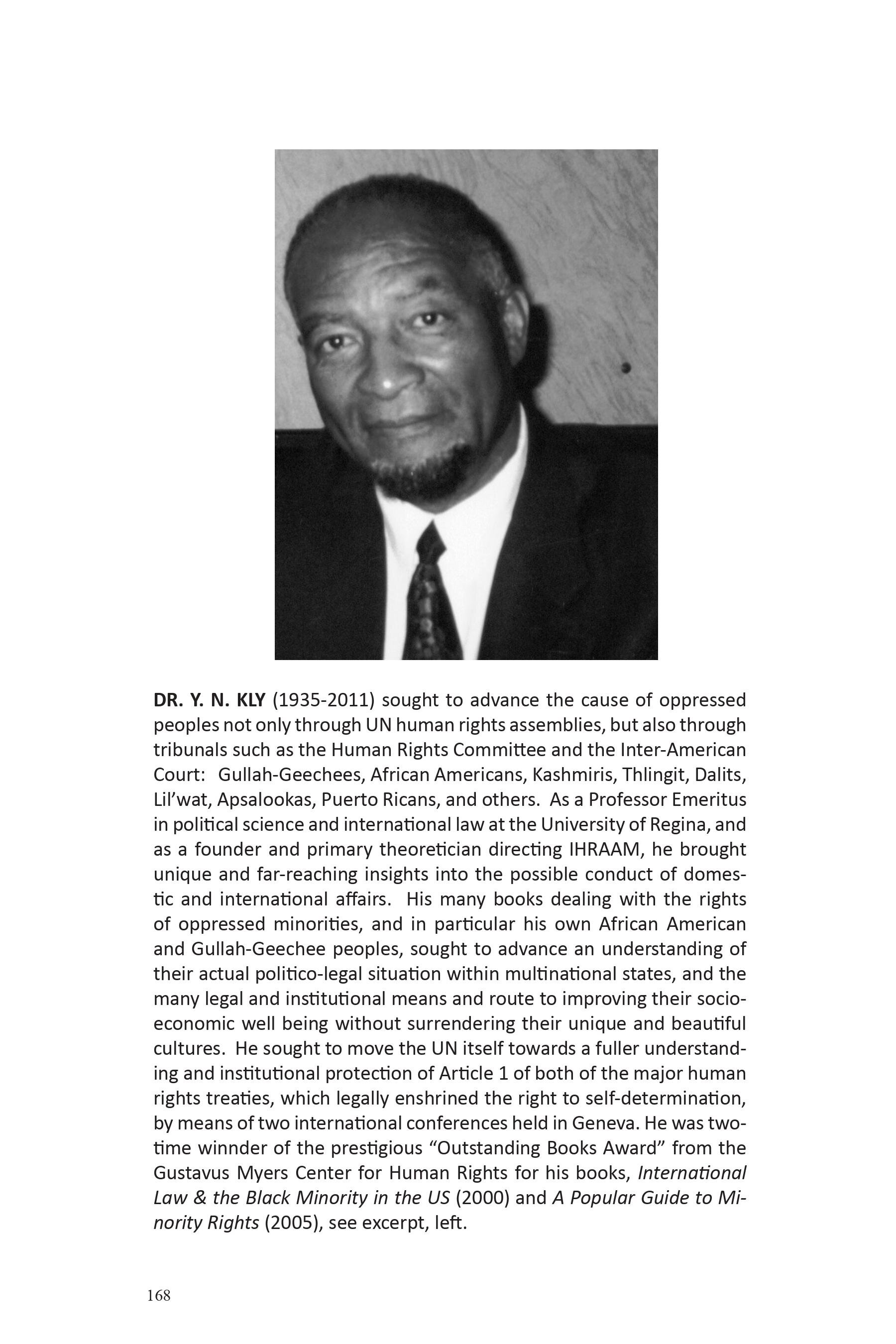

- Dr. Y. N. Kly, African-Americans and the Right to Self-Determination, Keynote Address to the Proceedings of the Conference on African Americans and the Right to Self-Determination, Hamline University, May 14, 1993.

In September 1992, the United States ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) developed under the auspices of the United Nations. The covenant protects the right to self-determination, the right to non-discrimination, the right to remedy, and the rights of minorities. That same same month, the United States was among three nations that narrowly escaped condemnation in 1992 by the United Nations Sub Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities for a pattern of gross human rights violations.. The complaint, submitted by the International Human Rights Association of American Minorities (IHRAAM) to UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali on April 30, 1992, was based on the continuing pattern of gross human rights violations suffered by African Americans in the United States, as typified by the case of Los Angeles motorist, Rodney King. Shortly thereafter, disillusioned with the prospects of life In America, I dropped out of Yale University and left the country.

I was seeking a place, a country of my own.

At this same time, IHRAAM hosted the Conference on African-Americans and the Right to Self Determination at Hamline University, May 14, 1993. In his Keynote Address, Dr. Kly asked, “What is the context for such a complaint? What is the legal vocabulary for a discussion of these issues? Do African Americans have a right to self-determination under international human rights law?” Further, Dr. Kly stated,

“At decisive points in the American past, events occurred that had the effect of arresting African-American socio-political and intellectual development, subjecting it to an orbit governed by the ‘strange attraction’ of historically-enforced paradigms, such as: no matter what actual effect majority decisions may have on the African-American, accepting these decisions represents not only what is best for African-Americans, but also the only possible way in which U.S. democracy can be expressed or maintained: to prove and confirm that the U.S. system, as is, is best for everyone, is the guideline for all legitimate African American analysis, leadership decisions and studies; to speak of the unique needs of the African-American community within the framework of government policy formation is racist or promoting segregation or racial isolationism; special rights, self-government, segregation and separation are all to be considered the same thing.

The original conditions that brought these paradigms into force and which locked the direction of African-American socio-politico development to this is, of course, too complex to be analyzed in this paper. However, suffice it to say that they are the conditions emanating from the shock and resulting tumult of enslavement, the lost recognition of rights as human beings, and all subsequent acts, terror, political control techniques and policies to which this particular community was subjected during its movement through legal enslavement, Jim Crow, and apartheid (segregation). From the vantage point of the intelligentsia of the dominant group, these same paradigms are encouraged and validated as a consequence of fears, privileges, customs and orientations growing out of having experienced the advantageous side of this historical development. In short, historically, a situation of Anglo-American domination has been viewed as both natural and desirable.

We feel it would be fair to assume that the patterns of African American leadership and the framework for decision-making that we see merging from the chaos of what is called the African American or black community, results from ‘sensitive dependence’ on these original historical circumstances.

If so, then our gathering here today is historic because it represents the first effort of African-American and indeed American thinkers to free their minds (in relation to the African-American question in the context of American development) from the intellectually crushing and oppressive paradigms that have served only to loop back toward the past, thus assuring that in relation to American pluralistic societal development, we shall continue to turn in purposeless circles around our original ‘strange attraction’ to various forms of enslavement and/or servitude, domestication and consequent materialism and dehumanization.

Our attempt today to begin the process of reorienting intellectual thought around the right to self-determination is first of all an act toward intellectual liberation, and is an historical landmark suggesting that we have finally broken free of the enslavement paradigms, and can now begin to contribute positively and meaningfully to African-American freedom . . . .“

In February of 1993, I intuitively understood the need to liberate my mind, to break free of the enslavement paradigms. The only way I knew how to do that was to physically leave America. At the time, however, as Dr. Kly surmised, I, like the rest of American and Afro-America, did not yet have the legal vocabulary for a discussion of these issues. I could only express frustration and rage for the injustice I was experiencing.

By that time, IHRAAM had facilitated communications between the National Organizing Committee for the Million Man March based in Chicago and were preparing for an intervention at a meeting of the UN Working Group on Minorities, May 26-30, 1997.

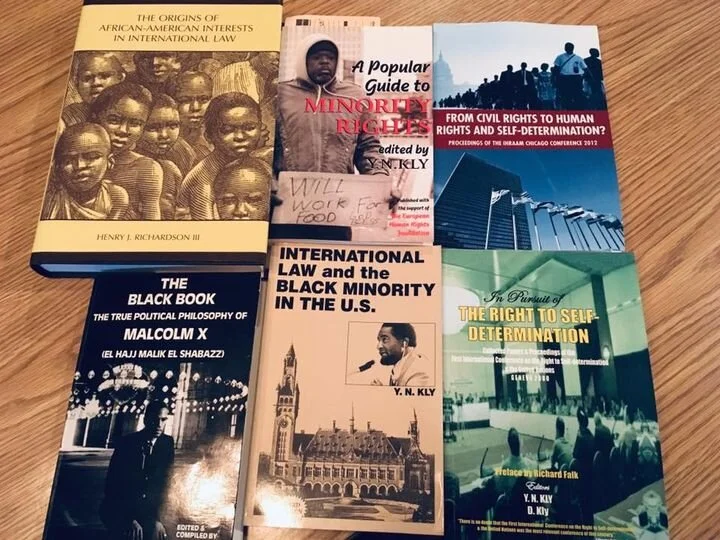

In 1996, however, I began learning from Irish El Amin Greene, Founder and Director of the Nkrumah Washington Community Learning Center (NWCLC) under the direction of Dr. Kly. El Amin had begun to direct my studies towards the law. Taking me to its old location, El-Amin explained to me the history of the National Council of Black Lawyers Community College of Law and International Diplomacy where he used to work. He provided documents about its co-founders Dr. Charles Knox and Dr. Y.N. Kly, both distinguished experts in international law and diplomacy, and provided me with textbooks on the U.N. and its procedures. One book in particular would change my life the way the Autobiography of Malcolm X had done: International Law and the Black Minority in the U.S. by Dr. Y.N. Kly. Along with another of his books, The Black Book (which details Malcolm X’s program to internationalize our struggle through the Organization of Afro American Unity),

I gained some clarity on what must be done and what I must do,

in order to gain relief from genocide and win reparations. I thus began writing Ras Notes: Conceptualizing Our Case for the U.N. At this time, I established communication with Dr. Kly’s International Human Rights Association of American Minorities (IHRAAM) and UHRAAP. I then began researching U.N. resolutions through the internet at DePaul University, and obtaining articles, petitions, and reports from NGO’s concerning our case. From these I began drafting the Petition of the Nkrumah-Washington Community Learning Center on Behalf of their Members, Associates and Afro-American Population Whose Internationally Protected Human Rights Have Been Grossly and Systematically Violated By the Anglo-American Government of the United States of America and Its Varied Institutions.”

At NWCLC, I was being trained to become an international legal advocate for African American self determination for the next generation. Lack of money for tuition and an intense contempt for higher educational institutions following my experience at Yale prevented me from formally enrolling in IHRAAM’s International Legal Studies Program in cooperation with Barrington University. I decided I would teach myself and learn on my own.

Alas, like Dr. Kly, I have arrived at the understanding that the question of a claim by African Americans for the right to self-determination “is largely one of self-definition within the context of geopolitical and legal reality.“ Moreover,

“An analysis of the African-American question thus should begin with a look at what level of political authority is absolutely needed by African-Americans in order for them to manage or resolve their most pressing crises, e.g. disproportionate representation in prisons, welfare, health care, educational dropouts, drug usage, mental institutions, homelessness, single parent families, etc. First, what is required to safeguard their right to be different and equal, and to achieve equal status with the majority? Second, what international legal responsibilities does the U.S. government have toward the African-American national minority that will assist it in achieving its political and socio-economic needs? Finally, which of these minority rights or U.S. legal obligations is it feasible to expect to be fulfilled in the present political, socio-economic and international legal climate? The second and last questions are dealt with in this presentation, and it is not appropriate to attempt a response to the first within the context of this Conference. It can perhaps be most usefully answered only in an African-American conference designed for that purpose - to reach consensus agreements that may be put forward as representing the African-American democratic and collective decisions, and leading to appropriate procedures for consultation and approval by the African-American people as a whole.”

The 2020 Presidential election has seen both candidates put forward their respective “plans” for Black America: LIFT EVERY VOICE: THE BIDEN PLAN FOR BLACK AMERICA and THE PLATINUM PLAN FOR BLACK AMERICANS: OPPORTUNITY, SECURITY, PROSPERITY, AND FAIRNESS. In addition, segments og the black community have put forward their plans for Black America as well: Black Agenda 2020 and #ADOS Black Agenda and Ice Cube’s A Contract With Black America. Unfortunately, as Dr. Kly predicted, ALL of these plans suffer from the ‘strange attraction’ of historically-enforced paradigms, that, despite their best intentions, perpetuate the crushing and oppressive forms of enslavement and/or servitude, domestication and consequent materialism and dehumanization of the dominant white (Anglo-American) majority paradigm that deviously seems both natural and desirable. In other words,

none of the 2020 plans for Black America have shifted from a domestic civil rights model to an international human rights model

and thus can not effect a true remedy for the welfare of the Black community. To rectify this, and to put forward a vision of what is required to safeguard Black America’s right to be different and equal, and to achieve equal status with the majority under an international legal framework (why Dr. Kly respectfully declined to do at the Conference on African-Americans and the Right to Self Determination) I submitted the

Agenda for Black America’s Restoration and Self Determination.

Somewhat to my surprise, the response to the Agenda for Black America’s Restoration and Self Determination has revealed the alarming civil, political and legal illiteracy of African Americans, despite the fact that in 1964, Malcolm X admonished us to internationalize our struggle and to move from civil rights to human rights. As Dr. Kly outlined in 1993,

“Concerning the content of the right to self-determination, Article 1 of the ICCPT stipulates that ‘State Parties . . . shall promote the right in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations.’ The ICCPR stipulates that under this right, peoples ‘freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.’ Although international instruments do not provide a succinct definition of the contents of the right to self-determination of peoples, the Declaration of Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States stipulates that the creation of a sovereign and independent State, or the acquisition of any other freely decided political status, are all means through which people can exercise the right to self-determination. . . . A large number of states such have introduced autonomy or self-government. . . . In many instances, self-determination has come to mean self-management, home rule, or merely the delegation of powers to a municipal authority with expanded functions. The title does not matter so long as the central government agrees to power sharing and leaves a sufficient and acceptable amount of control over minority affairs in the hands of group representatives. Sufficient self control by certain groups over their internal affairs is seen in human fights law as essential for protecting dignity, identity, and diverse customs, and placing groups on an equal footing with other parts of society.”

This is essentially the substance of the Black Lives Matters call for community control of police. Such a call, moreover, is popularly accepted by the Black community. However, why limit such a demand to just one area of the black experience? Why hasn’t the Black Community formulated a comprehensive demand for “community control” of all areas and institutions affecting Black lives? Why was no comprehensive agenda for Black autonomy or self determination put forward until now? Why has no platform framed their agenda or even referenced the ICCP of which the United States is a party to?

The answer is: civil, political and legal illiteracy.

Dr. Kly continued,

“When members of minorities demand, as the traditional African-American leadership has always done, no more than equal treatment, which has been increasingly interpreted in U.S. courts to mean the same treatment, the ordinary rules concerning non-discrimination apply. However, if a national minority such as African-Americans began effectively to demand, in some respects, differential treatment for the purpose of achieving equal status, it becomes necessary to distinguish between the domain which is of common concern and that which is specific to the members of the minority. In all matters of common concern, the principle of equality and non-discrimination continues to reign supreme. The first level of obligation for the sovereign state, the United States in this case, is to respect the equality of all individuals before the law. This presents the first problem: should the law be the same for all groups? To what extent, and in regard to which circle of persons under which circumstances, should a legal or political system for that particular group be recognized? To the extent that it is found necessary in order to allow for the preservation of the identity and equal status of the group, certain matters may have to be transferred to the area of separate concern. . . . The first level of state obligation is inextricably intertwined with the second level, which is to assist its inhabitants in enjoying their human rights through fulfilling their justified claims to minority rights as spelled out in human rights instruments. This means that equal enjoyment of human rights must be achieved through active legal regulation and its administrative and financial implementation. . . . In the case of African Americans, the use of affirmative measures, non-territorial self-government, or certain forms of institutional autonomy, can help to redress past discrimination and/or inequality in the enjoyment of rights by recreating equal opportunity in fact. This requires an affirmative definition by the group itself of its wishes and or its minority or ‘nation’ identity (the subjective factor). Self-definition for African-Americans will have the effect of defining their status for the purpose of justifying their entitlement to transitional affirmative measures, special rights or minority rights, and compensation for gross violations, depending on the democratic demands of African-Americans.”

The United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities states:

States shall protect the existence and the national or ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic identity of minorities within their respective territories and shall encourage conditions for the promotion of that identity.

States shall adopt appropriate legislative and other measures to achieve those ends.

As Dr. Kly, noted, the Declaration, which is not legally binding, gives us direction as to the interpretation of Article 27 of the ICCPR, which is legally binding on state parties ratifying the Covenant. Why aren’t we demanding and exercising our international rights???? Again, African Americans haven’t shifted from a civil rights framework to an international legal/human rights framework because of the ‘strange attraction’ of historically-enforced paradigms, that, despite their best intentions, perpetuate the crushing and oppressive forms of enslavement and/or servitude, domestication and consequent materialism and dehumanization of the dominant white (Anglo-American) majority paradigm that deviously seems both natural and desirable.

This explains why, in 2020, in the midst of complete failure of United States democracy and a fraudulent presidential election between two known racists, one a narcissist and the other a pedophile, the overwhelming expression of the black community is “VOTE! YOUR ANCESTORS DIED FOR THE RIGHT!”

This represents a blatant psychosis, a form of Stockholm syndrome, when it comes to the question of African American civil, political and legal status. Shifting the paradigm from civil rights to international human rights is provoking African American cognitive dissonance. I witnessed this first hand during a panel discussion with a black professor of African American history, who, without even reading the Agenda for Black America’s Restoration and Self Determination, began ignorantly attacking it.

As to the possible claims to self-determination that African Americans could possible make at this time, Dr. Kly identifies three:

“(1) First, African-Americans may wish to make their claim to international protection for the right to self-determination based on an agreement between themselves and their government. This would mean first bringing their political and socio-economic grievances to the attention of the U.S. government with a plan for internal self -determination that could feasible resolve those grievances. Any such agreement reached would be recognized in international human rights law. . . .

(2) Second, African -Americans may claim systematic and institutional discrimination, present violations of human rights (including minority rights) and past gross violations of human rights (including slavery and apartheid), claiming that this has left them in an inferior political, social and economic situation in the United States, and in an underdog position in relation to other peoples in the world, from which they can only escape through the adoption of some form of autonomy, self-government, or institutional self-management, insofar as, over the past few decades, equality before the law, non-discrimination and affirmative action have proved inadequate. Thus, a demand for special rights under Article 27 of the ICCPR would appear appropriate. If the U.S. government refuses to recognize their special rights and is still unable or unwilling to provide for equal status (assuming that they have been democratically demanded by a representative African-American assembly or council), then, backed up by references to ‘recourse… to rebellion against tyranny and oppression’ set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the language in the Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States, a third legal claim becomes available.

(3) The third option would probably be the most disruptive to positive relations between groups in the United States. African-Americans could claim they have a right to self-determination as a revolt against oppression and the violation of their human rights. This would call attention to the long history of gross violations of their human rights and the continuation of this pattern into the present.”

The Agenda for Black America’s Restoration and Self Determination is a combination of options 1 and 2 above.

Of greatest importance and thus concern, however, is Dr. Kly’s conclusion:

“While in theory we have concluded that African-Americans do have the right to self-determination in international law, we must in all reality remind ourselves that African-Americans have not made made self-determination or minority rights demands. Nor are they creating the political structure required to do so..”

During Panel Discussion I at the conference, Keith Ellison stated,

“This condition of Black people, the pseudo-citizenship, gives African-American people the right to forge their own separate, independent identity, if they should choose to do that. I think what is needed is that African-American citizens should have a right to vote on that question. Should we remain with the American state, the United States, or should we opt out of that arrangement? The common estimation and legal status of African-Americans throughout American history brings African-American citizens into the modern day position where any effort to integrate with American society is rebuffed. It is not that African-Americans have, by and large, been opposed to integration and pluralism. Whites, particularly those possessing political and economic power, have resisted inclusion. What I am saying is that if a national minority is refused the right to be integrated, then the larger society should allow and assist the national minority to opt for an independent destiny.”

Following Mr. Elliison, Dr. August Nimitz said,

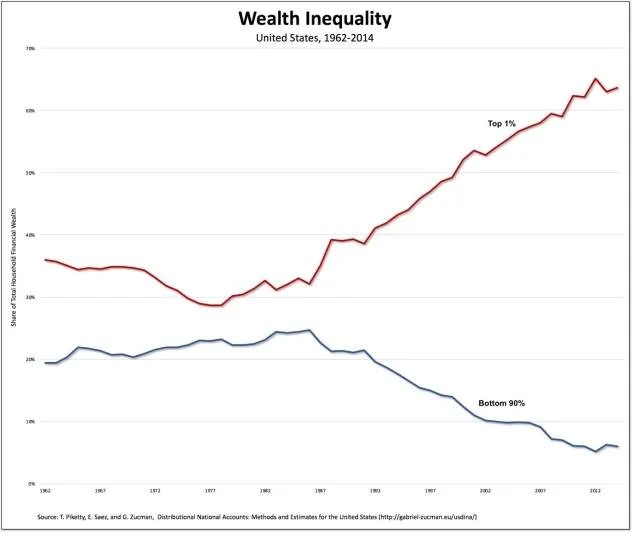

“The question that Dr. Kly raises at the end of the paper is why aren’t there any demands at this particular time. It seems to me the reason is that there were in fact very real changes that took place in this country in the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement that led to, if not integration, then a degree of upward mobility for increasing layers within the Black community - a degree of upward mobility that reflected something else that was taking place within U.S. society, increasing class polarization within U.S. society as a whole.

Within the black community, you begin to see increasing disparities in income and wealth. In fact, there was a layer of people who benefited quite well materially from the Civil Rights movement.

I would argue fundamentally that the quest for self-determination throughout history on the part of the oppressed minorities has almost invariably been led by elites and intellectuals. This was the experience of Nineteenth Century Europe, and it has been the experience of Twentieth Century Africa and other third world countries. The reality is that as opportunities have become available for elites and intellectuals within the Black community to move, to become upwardly mobile, the requests and demands for self-determination have tended to abate. To the extent, to make a forecast, that those desires, those quests, are not entirely fulfilled, we may anticipate again a demand for self-determination, but as long as the hope exists, and as long as the possibilities exist for that kind of mobility, I am not convinced that we will see a demand for African-American self-determination in the immediate future.”

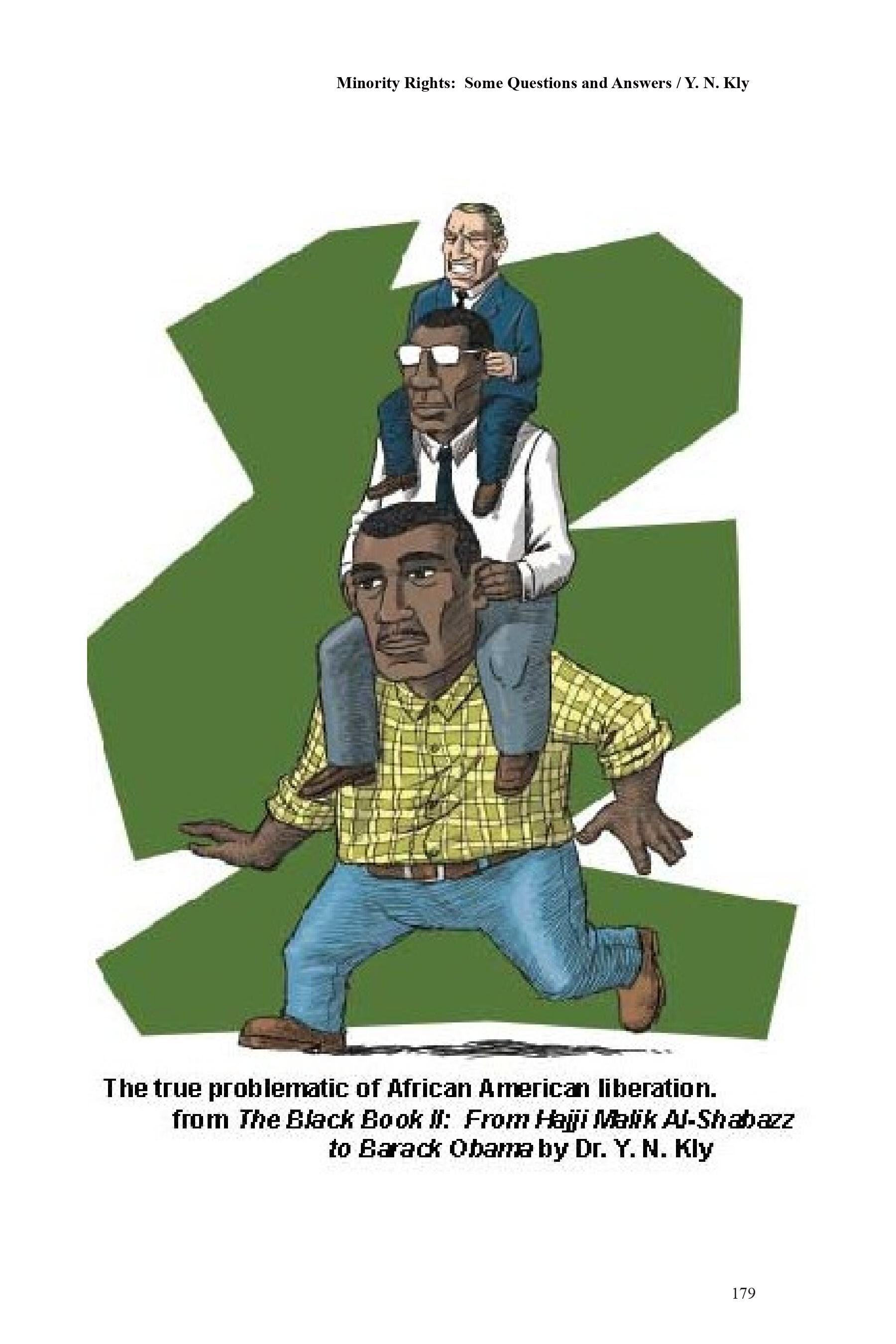

From this understanding, we can further understand how the Presidency of Barack Obama was used to pacify the Black Community and prevent and such African American demand for self-determination.

Neely Fuller Jr. calls this strategy of providing the black community with hope in order to prevent them from claiming self-determination as SHOWCASISM:

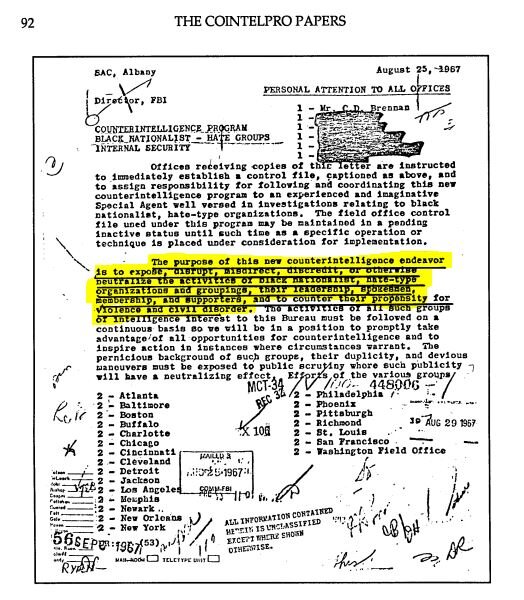

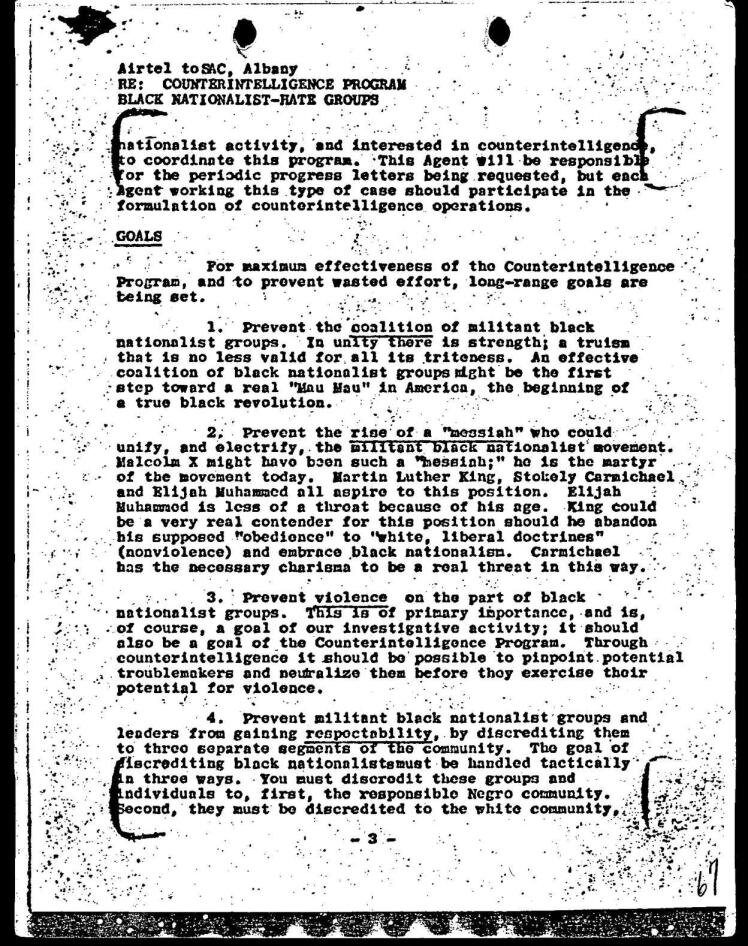

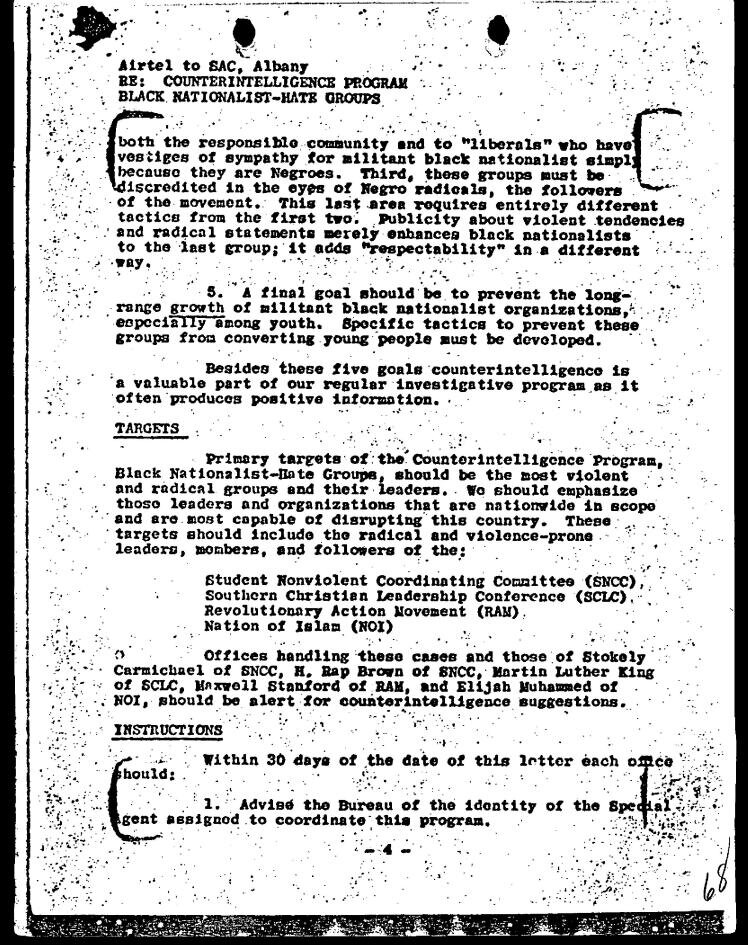

Here we must revisit Director J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI's COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program) that was aimed at investigating and disrupting dissident political groups within the United States. Hoover clearly stated COINTELPRO’s goal to prevent any African American claim for self-determination:

“For maximum effectiveness of the Counterintelligence Program, and to prevent wasted effort, long-range goals are being set.

1. Prevent the COALITION of militant black nationalist groups. In unity there is strength; a truism that is no less valid for all its triteness. An effective coalition of black nationalist groups might be the first step toward a real “Mau Mau” [Black revolutionary army] in America, the beginning of a true black revolution.

2. Prevent the RISE OF A “MESSIAH” who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement. Malcolm X might have been such a “messiah;” he is the martyr of the movement today. Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael and Elijah Muhammed all aspire to this position. Elijah Muhammed is less of a threat because of his age. King could be a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed “obedience” to “white, liberal doctrines” (nonviolence) and embrace black nationalism. Carmichael has the necessary charisma to be a real threat in this way.

3. Prevent VIOLENCE on the part of black nationalist groups. This is of primary importance, and is, of course, a goal of our investigative activity; it should also be a goal of the Counterintelligence Program to pinpoint potential troublemakers and neutralize them before they exercise their potential for violence.

4. Prevent militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining RESPECTABILITY, by discrediting them to three separate segments of the community. The goal of discrediting black nationalists must be handled tactically in three ways. You must discredit those groups and individuals to, first, the responsible Negro community. Second, they must be discredited to the white community, both the responsible community and to “liberals” who have vestiges of sympathy for militant black nationalist [sic] simply because they are Negroes. Third, these groups must be discredited in the eyes of Negro radicals, the followers of the movement. This last area requires entirely different tactics from the first two. Publicity about violent tendencies and radical statements merely enhances black nationalists to the last group; it adds “respectability” in a different way.

5. A final goal should be to prevent the long-range GROWTH of militant black organizations, especially among youth. Specific tactics to prevent these groups from converting young people must be developed.”

We have now reached that long-range horizon and can conclude that COINTELPRO was, indeed, effective in preventing militant black nationalists groups and leaders from gaining respectability.

AGAIN, NO MAINSTREAM AGEND FOR BLACK AMERICA USES ANY SELF DETERMINATION FRAMEWORK EXCEPT THE AGENDA FOR BLACK AMERICA’S RESTORATION AND SELF DETERMINATION.

For the benefit of increasing the civil, political and legal literacy of African Americans, I include below

Minority Rights: Some Questions and Answers (excerpt from A Popular Guide to Minority Rights, ed. Dr.Y. N. Kly, Clarity Press, Inc. as well as

the full-text of From Civil Rights to Human Rights and Self Determination? Proceedings of the IHRAAM Chicago Conference 2012.

Minority Rights: Some Questions and Answers

QUESTION: Why should African-Americans look to international human rights law for help achieving equal status and equality in America?

International human rights law promotes norms of minority treatment that are more wide-ranging and have been more successful inpractice than limited concept of civil rights (non0discrimination and equality before the law, which in the United States is interpreted tomean the same treatment). These norms reflect the modern world’s experience in trying to accommodate the problems of minorities bygiving the historically evolved situation and circumstances of the minority group adequate consideration, leading often to positive stateaction and different treatment, in view of their different requirements.Viewing the problem of minorities within the international context prevents the error of thinking that local minorities’ problems are unique(and hence insoluble). By enabling the African-American problem to be viewed within the context of a whole range of problems whichhave typically arisen for minorities worldwide—by the mere fact of their being a minority -- we can see that African-Americans’development problems are essentially caused by the fact that they are a minority in a state that refuses to recognize or provide for theirminority rights or to permit any form of community control. Segregation attempted to institute the cultural assimilation of African-Americans while maintaining their physical separation.

QUESTION: International human rights law as a model for minority rights is all well and good, but who says America will payany attention?

Political pressure created by African-Americans demanding these rights, in conjunction with international pressure, will createcircumstances that will raise the cost both domestically as well as internationally, of denial of these rights beyond the benefit of notproviding for them. To maintain the creditability of its position as a leading power, the United States must provide for minority rights,should these rights be demanded. As a matter of fact, in cases where effective demands are made by Native Americans, we have seenpositive action on the part of the United States government. Faced with an effective contingent of Native American lobbyists from theUnited Sates and politically forced to respond in an internationally supported forum concerning the needs of the world’s indigenouspeoples, the United States delegate to the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations was forced to respond, according tothe UNPO Monitor, that:

…although human rights of indigenous people is promoted in the United States, the promotion of the rights of dignity and “equality” are not sufficient. Expressed support of the basic goals of the draft Declaration [on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples]. Offered a working model on how the rights of indigenous people can be recognized and implemented—on the right to self-determination, raised the issue of the recognition of tribal self-governance and autonomy over a broad range of issues as a positive development in the national level. Highlighted the uniqueness of this concept of self-governance which considers a “government-to-government relationship.” Finally, expressed determination to explore how this concept of self-determination might be translated into international terms.

-Americans were to vote under a system which gave them full representation according to their votingnumbers, insofar as they are a numeric minority, they could still continue to be outvoted on every issue where their interest might clashwith that of the majority. There would still be no (institutionalized) way which ensured that the system would address their specific needsor permit African-American communities to address their needs, themselves.

QUESTION: Surely, if individual African-Americans are elected to office, this should mean greater clout for the community? While African-Americans holding elected office doubtless feel strong obligations to their community and project their concerns inwhatever arenas they may be functioning in, such officials also have obligations to the other communities over whom they also havejurisdiction. Frequently, in fact, elected black leaders have operated what Cynthia Enloe, writing with regard to black Americans, terms asub-machine:

QUESTION: Why hasn’t civil rights worked?

As a minority in a majoritarian democratic system (as opposed to a pluralist system), African-Americans don’t have the voting powerto enforce adequate consideration of their needs. American electoral procedures such as the single non-transferable vote (as opposedto proportional representation) and at large municipal voting (as opposed to the ward system) are all geared to ensure majoritydomination. However, even if African-Americans were to vote under a system which gave them full representation according to their votingnumbers, insofar as they are a numeric minority, they could still continue to be outvoted on every issue where their interest might clashwith that of the majority. There would still be no (institutionalized) way which ensured that the system would address their specific needsor permit African-American communities to address their needs, themselves.

QUESTION: Surely, if individual African-Americans are elected to office, this should mean greater clout for the community?

While African-Americans holding elected office doubtless feel strong obligations to their community and project their concerns inwhatever arenas they may be functioning in, such officials also have obligations to the other communities over whom they also havejurisdiction. Frequently, in fact, elected black leaders have operated what Cynthia Enloe, writing with regard to black Americans, terms asub-machine:

a patronage and favor-dispensing organ nominally controlled by a politician from a relatively weak ethnic group [whose] owninfluence and resources depend on access to the resources of the larger machine controlled by politicians of another community. In essence, the sub-machine boss is the loyal lieutenant of the machine boss; but he is permitted enough autonomy to build a personal power base of his own so long as it never rivals that the senior patron.

These representatives, while they may be African-American, cannot be seen to be speaking for the African-American communities. Their position is therefore very ambiguous where the interests of majority and minority conflict. While a number of mayors in majorAmerican cities are now African-American, in many instances it cannot be said that the African-American communities that have electedthem have benefited. So the question remains: who has the legitimacy and authority, as conferred by the democratic process, to speakfor African-Americans? Is there a need for an African-American election? Are African-Americans enjoying democracy in America, orhave their interests and needs, insofar as they differ from that of the majority population, been consistently submerged by the interest ofthe majority Anglo-American ethny? Is the subordination of African-American need to majority interest even visible in the very courtdecisions which enforced their civil rights since, as Derrick Bell has observed, “Successful court decisions in relation to civil rightscoincide with those case decisions that also serve to benefit the majority ethny even more”?

QUESTION: Were we misdirected when we struggled for civil rights and against the “separate but equal” doctrine?

No. At the time, there really wasn’t much understanding of discussion of the options (nor indeed, was conventional international lawas developed with regard to minority rights as at present). Resistance to segregation, the American version of apartheid, and indeed,the image of apartheid and Bantustans as practiced in South Africa, may have weighed against the maintenance of separate institutions,in the presumption that they would necessarily be controlled by Anglo-Americans and thus kept unequal. However, the African-Americanpeople may not have generally understood that what may have appeared as the alternate process, “integration,” was in realityassimilation, and would encourage the dismantling of the existing degree of African-American economic, political and educationalinstitutions, communities, families, etc.Most important to note is that African-Americans were neither separate nor equal. The doctrine, while using the words “separate butequal” was actually a doctrine of segregation and racism. All institutions of the African-American community were under the indirectcontrol of the Anglo-American majority ethny through the apparatus of the state: school curricula, the justice system, the licensing systemfor professionals, etc. Thus, African-Americans have never fought for nor against a separate but equal system. They have foughtagainst racist (Anglo-American) oppression and for civil rights, assuming that civil rights was the way of overcoming Anglo-Americanoppression, while racism was simply the tool to maintain the oppression. While African-Americans may have brought about the end of official constitutional-legal discrimination (segregation), they have notachieved equal status (particularly as a group) in the electoral system, or indeed, in terms of general level of political and economiccontrol in any sector. So while the struggle for civil rights (the rights of a citizen) has been valuable, it has not provided equality or equalstatus in law or in fact. It has provided for African-Americans to be treated the same as Anglo-Americans regardless of whether this“same” treatment leads to greater inequality in fact or not, and regardless of whether treating African-Americans as the same legallyproduces greater or lesser legal equality. It provided for their cultural and political assimilation into the Anglo-American underclass, fortheir disappearance as a separate nation; in short, it provided for ethnocide.

QUESTION: Does non-discrimination (equality before the law) work for African-Americans?

Apart from marginal remedy for some individuals, not at all, because most discrimination is institutional, structural and systemic. The main recourse provided by equality (same treatment) before the law/non-discrimination is threat of court action. As any who haveever undertaken such legal action can testify, it is a tremendously costly and lengthy process, with the outcomes always uncertain andthe proofs concerning individual situations burdened by subtleties often beyond the power of the courts to capture. While successfullawsuits likely do cause some attitudinal discrimination to abate, it is likely that attitudinal discrimination is pushed underground, whilesystemic discrimination remains, disguised in legitimate institutions, politico-legal mandates, prerogatives and necessities. A further problem with attempting to solve discrimination problems through the courts is the fact that, increasingly, the United Statesjudicial system regards equal treatment “of rich and poor alike” as before mentioned, to mean the same treatment (in abstract, makingthese two unequals equal in such a way as to seem concerned rather with preventing the possibility of discrimination against the rich)and thereby discounts factors that differentiate the parties concerned, such as poverty, historic oppression, etc. Constant litigation on the part of aggrieved individuals is not the solution but remains a symptom of the problem, which is systemicand institutional.

QUESTION: If non-discrimination laws don’t end discrimination, how do you end discrimination?

First we should consider some of the sources and purposes of discrimination. Discrimination does not derive from a free-floating attitudeof “racism” arising spontaneously in the minds of some “bad people” who “don’t like [black] people.” Typically it evolves dialecticallythrough specific historical events leading to the creation of systemically generated and ensured inequalities, whether its concerns today’sthird world economic refugees, victims of the neo-colonial international economic order, or the situation of the African-Americans, victimsof a long history of one nation’s official systemic policies devoted to ensuring the dominance of Anglo-Americans. The material andpsycho-social hierarchies generated by systemic inequality in turn condition a web of attitudes, fears, distastes, and hostilities.

However, awareness of this systemic causality plays little part in most inter-group relations—not just because of the complexity ofthe understanding required, but also because what is really at issue is not just majority distaste for this or that trait of the discriminatedgroup. The issue is collective power relations between the groups, and the individual power of group members that either benefits orsuffers from this unequal relation. These are pocketbook issues and concerns “having” (as opposed to “sharing” which can be properlyviewed as “having an appropriate part of,” or negatively viewed as “having less,” or at minimum as “maximizing your losses,” insofar asfailure to share may result in a situation in which the pie itself is destroyed.) It concerns habits of interaction, customary assumptions andso on, all of which are measured on a scale of relative privilege.

Psycho-spiritual complexes deriving from the long history of official systemic discrimination and gross human rights violation in whichAfrican-Americans have been subjected, lead any in the majority culture to take it for granted that they should receive priorityconsideration over African-Americans in the allocation of social benefits, i.e. jobs, education, housing. Many, while refusing to admit therelevance of historical/systemic factors to the present day African-American condition, consciously and unconsciously anticipate and fearretaliation for their disproportionate privileges. Few can be impervious to the distorted and inflammatory depictions of African-Americansin the major American media, or indeed the reality of their disproportionately negative standing in all typical Anglo-Americanmeasurements of social well-being (income, life expectancy, health, education, etc.) Such a web of motivation often leads the majoritypopulation to a reluctance to surrender any of the advantages and privileges which have been directly tied to its historical role asvictimizer. Far better to blame the victim than to admit or dwell on causal factors which could lead to its recognition of both the justice,need and wisdom of surrendering its position of superiority, both material and attitudinal, which translates into the proportionate sharingof political and economic power and resources.

Equally, the remediation of such ingrained attitudes and long term abuse as has existed in the African-American case might requirenot merely the alleviation of material inequality, but also a form of public repentance as exemplified by an official admission of andapology/reparations for the history of systemic discrimination and gross human rights violations.

Once a measure of equal status has been established between groups, any tendency to discriminate would likely lose its deep-rooted and destructive basis, and where it remained, become similar to the milder rivalries and frictions which exist between cultureswhich nonetheless recognize each other’s full human equality, e.g. the rivalry between the British and French, etc. It is in such cases thatnon-discrimination and recourse to the courts is most effective. However, in situations where the historical situation has led to deep andpervasive structural inequalities in the relationship between majority and minority, the effectiveness of policies of non-discrimination forcreating equality are negligible. So the question is one rather of establishing equal-status and interdependence between groups. Within the American framework, the notion of how nondiscrimination policy can succeed in producing equality probably goes somethinglike this: if every instance of discrimination is prevented, then discrimination as a whole will be ended, and thus meritorious individuals,who exist in similar proportions in all groups, will rise to their natural place in the general social order, and hence all groups, by naturalprocess, will end up having a proportionate share of the social product, and a proportionate standing in all social indicators, i.e. equality. This view of non-discrimination is concerned, not so much with protecting the right to be different, as with insisting that difference not benoticed or not matter, when it comes to allocating benefits, etc. Inactuality, it becomes a game of “let’s pretend”: let’s pretend that thecontroller (the employer, the landlord, the banker, the real estate broker, the university professor) doesn’t notice that you are a minoritymember; he/she will treat you as if he thought you were equal (the same as an Anglo-American) although actual social conditions andprejudicial Anglo-American social criteria may lead him/her to assume (rightly or wrongly) that the schools you attended as a child wereunder-financed, that the community your grew up in and presently live in is beset by social problems resulting from unemployment,underemployment or low-wage employment, that your ability to excel or even function in the job may be impaired by the whole gamut ofsocial factors which beset you as a member of a devalued group, thereby rendering you less capable, less reliable, and so on. This notonly leads inescapably to hypocrisy, but is also highly insulting. Insofar as the collective identity of the minority is burdened by stigma, sois the standing of the individual, whether the attendant presumptions apply to him/her or not.

There is no way for individuals tocompletely, or even sufficiently, escape the stigma attached to the collective identity even if they do manage to escape the materialconditions. In short, the game of pretending to ignore differences is a way of suggesting that there is something wrong with beingdifferent (non-Anglo-American): a way of imposing cultural domination and ignoring your right to be who you are, with equal status.

Non-discrimination can only be achieved by ensuring the right to be different by whatever means that may require. It may requireboth an attempt to put a stop to negative action, as well as taking positive action on behalf of preserving the identity and promoting theequality of discriminated-against groups through politic0-legal or socio-economic policies directed specifically towards the groupconcerned.

QUESTION: Maybe discrimination is rooted in human nature and can’t be prevented?

This is unlikely. Most research shows that the source of discrimination lies in a historical oppression or devaluation which issystemically implemented and ensured by the state. Thus, it can only be appealed against to the state that is also its creator andpreserver. As far as minority rights are concerned, the key may lie in sidestepping the issue of discrimination; in getting equally throughminority control of institutions, and leaving prejudice to its most natural correction: the development of respect and esteem deriving fromequal-status relations and the creation of situations of interdependence among groups.

Discrimination counts most and is maintained when one group has to go to another group which is prejudiced against it for fulfillmentof basic needs: shelter, housing, education, capital; that is, when one group is made dependent on another, and when the law of thatgroup comes to feel that they are superior to the dominated group, and that there is something wrong with any number of aspects of thedependent group. If African-Americans run their own communities, their own socio-economic institutions, then they no longer have to tryto achieve their needs in and through socio-economic institutions (etc.) controlled by the Anglo-American community. They are then ableto provide for their own through initiatives enabled by access to proportionate share of the public purse (i.e. tax revenue, etc.), thuscreating conditions of interdependence between groups, enabling the marginalization of the problem of discrimination.

QUESTION: Aren’t rights or measures that are just for minorities a kind of reverse discrimination?

No. The concept of reverse discrimination as used in the United States is an effective way of attempting to ignore the existence ofminorities and minority rights, and psychologically prevent minorities from seeking rights outside of their control. It suggests that thehistorical situation of the dominant group is the same as that of the devalued minority, and that where there is no difference, no right tobe different, all should be treated the same—even if the effects maintain inequality for the minority. International law specifically militatesagainst the concept of reverse discrimination. See Article 1:4 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination(CERD) and 8:3 of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious, and Linguistic Minorities, inAppendix II.

QUESTION: Do special measures and special rights apply to all minorities? What about homosexuals, or the disabled? What about Greek or Irish Americans?

Minority rights are essentially collective rights as they exist for the purpose of eliminating minority oppression and inequality. Thereforein a technical sense, the word “minority” and the word “victim” in domestic law become similar when the right to international protection isevoked. It is evoked because some important aspect of the minority’s rights and needs is being denied, ignored or trampled upon by themajority. Customary international law suggests that rights involved in Article 27 of the ICCPR, as far as the United States is concerned,apply particularly to the national minorities: the African-Americans, Native Americans, and Chicanos. These minorities existed collectivelywithin the state as the time it was constituted, and are not seen as immigrants from another state within the international system.

Immigrant minorities, on the other hand, have made individual choices to leave duly constituted states in which they were citizens;there is implicit in the notion of immigration, the acceptance on the part of the immigrant of the desire to assimilate. This does not mean,however, that the state may not be willing to accord them certain resources or special rights. Canada, for instance, has such amulticultural policy which benefits its many immigrant minorities. This does not put them on the same plane, however, as Canada’snational minorities, the aboriginal peoples and the French Canadians, who either enjoy or are recognized to have the right to significantlygreater politico-legal control of socio-economic and cultural institutions, and who seek to be regarded in full equality as founding nationsof the state.

Social minorities (gays, the disabled, women [so-defined because of their non-dominant position], etc.) do not figure within theconfiguration of national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities protected by international minority rights law. However, other humanrights law applies to them.

QUESTION: What is the difference between special measures and special rights?

While special measures refer to measures taken on behalf of the group which cease to exist once the minority achieves equal statuswith the majority, special rights are permanent and are accorded with a view to recognizing the minority’s right to remain different, tocontinue to exist and develop as a minority or nationality distinct from the majority culture, while interacting with it on a basis of equalityand interdependence.

Special rights may include the notion of proportionality, widely recognized as effective for reducing group conflict and ensuringequal development. It may be introduced in a limited manner (e.g. in only some sectors such as hiring in the civil service) or extensivelyin most public jurisdictions. IN Switzerland, for example, the French, German and Italian populations share federal executive, legislativeand judicial positions proportionally; proportionality is even taken into account in the armed forces. In Belgium of the 1950’s-60’s, a near50-50 form of proportionality was extensively used. Belgium’s 1971 constitution stipulated that with the possible exception of the primeminister, the cabinet must comprise an equal number of Flemish and French ministers. The same devotion to the principle of equality isalso found in Belgian government’s allocation of resources. When railway lines had to be abandoned, when industrial developmentprojects were sited and financed, when road were built, the decisions were made on the basis of equal shares in the benefits for eachnationality or minority.

In particular, special rights creates pluralist democracy in order to assure equal status of all nations or minorities in the state—minority control of institutions in various sectors, such as education, healthcare, the justice system, culture, welfare, tourism, etc. Controlover these sectors, whether achieved through autonym, devolution, federalism, etc. permit minority control over important elementsaffecting its well being and daily life. This allows the minority a measure of self-determination without threatening the territorial integrity ofthe state.

QUESTION: Can we talk about self-determination and not be talking about secession?

Yes. Self-determination has come to be divided in scholarly discourse between external self-determination (the right of a group tosecede and become fully politically independent) and internal self-determination (where a group exercises political rights, among themthe right to control over jurisdictions of social activity such as education, health, criminal justice, etc. in varying degrees, while remainingwithin the existing state).

QUESTION: In Article 1 of both Covenants, self-determination is said to be the right of “peoples.” Is self-determination aminority right, too?

Many scholars such as Ian Brownlie argue that trying to establish differences between groups such as “peoples,” “minorities” and”indigenous peoples” and their respective rights is fruitless, insofar as the issues are the same, and “the segregation of topics is animpediment to fruitful work.” In his keynote address to the Hamline Conference on African-Americans and the Right to Self-Determination reprinted herein, Dr. Kly further advances these arguments. In practice, varying degrees of internal self-determinationhave been accorded to both peoples and national minorities in order to promote harmonious inter-group relations.

When used in relation to national minorities, self-determination is concerned primarily with internal jurisdiction, and does not permitthe right of succession or threat to the territorial integrity of the state. The word “autonomy” is being used with greater frequency now, inthis regard. While “internal self-determination” as it relates to national minorities, and “autonomy” can be regarded as functionally thesame, there is no escaping the liberating connotations which continue to cling to the former term.

QUESTION: What are African-Americans? A people? A racial, ethnic or national minority?

There is no internationally agreed upon definition for either peoples or minorities. Both share many characteristics. Also stateshave devised solutions in domestic law to permit nationalities to exercise varying degrees of self-determination. While a commonlanguage, culture and religion may play an important determining role in the process of definition, the subjective factor—self-definition,the desire and ability of the group concerned to assert its will to exist as such, to be and to develop as a group, and to express its needfor “autonomy” or some form of internal self-determination to achieve equal status—is a major factor in determining how a group isdefined in international law.

Keeping in mind the international legal relationship between the word minority and the word victim, the most important factor callingforth legitimate demands for )internal) self-determination may be their historical circumstances, and the extent to which they have beenunable or unwilling to assimilate, or have been prevented from assimilating by the majority culture, and remain trapped in a condition ofpermanent inequality vis-a-vis the majority.

While there has been no internationally accepted definition of national minority (let alone minority), this term continues to appear ininternational legal texts. Some have argued, in fact, that this is the only type of minority that truly has rights to international protection, insofar as all other are essentially immigrant or social minorities, and are covered by other human rights instruments.

While classification of African-Americans as a national minority abrogates the issue of whether they are an ethnic minority, it seemsclear that their self-definition as African-Americans; their recognizability anywhere in the world as such; their distinctive music, dance,cuisine, dress and manner; and their sense of a shared history would clearly make the ethnic definition, too, and an appropriate one.

QUESTION: Do African-Americans have a unique cultural identity?

Many factors make up a people’s or national minority’s unique identity; these concern shared characteristics such as language,religion, or a common heritage. While most national minorities do to some degree share many of the same characteristics (as majorities,and indeed as the people of many independent states), it is important to remember that the African-American culture was consolidatedunder conditions of oppression. It would be difficult to argue that there is common history between the enslaved and the enslaver, i.e. ashared experience of that history, a shared interpretation of that history, or a shared evaluation of its major actors.

Assuredly, African-Americans have a unique identity. Their roots go deep into Africa, not Europe. It would be nonsensical toassume that , over the passage of generations, parents transmitted to their children nothing of the practices and understandings withwhich they themselves have grown up—even under the hostile conditions of enslavement, which attempted to erase all prior identities. African-American culture in the southern United States still retains many direct linkages—the basket weaving women of South Carolina,the syntax and vocabulary of the Gullah language which many have claimed provides the basis for what is commonly referred to, andcoming to be taught as, African-American language, etc.

Despite the long history of theft and borrowing from African-American blues and jazz, there is nonetheless recognition of thedistinctive cultural source of this music. Even today, the reference to “crossover” music asserts a continuing difference anddistinctiveness of the African and Anglo-American musical cultures.

While African-Americans, like Mexicans, Cubans, French, etc., do to some degree share some of the same religious beliefs asAnglo-Americans, they also practice many religions not generally practiced by Anglo-Americans. Within the African-American community,we find, Muslins, Holly Rollers, the Green Door Society, the Yoruba, the Black Hebrews, Daddy Grace, Father Divine, and so on. Thereligious culture of African-American Christian churches is strikingly different from that of Anglo-American churches, to the extent thatsome worship an African Christ. Most African-American Christians still belong to the African Methodist Church.

QUESTION: Why does having a unique identity matter? Why can’t everybody just be the same. After all, we’re all alikeunder the skin.

Unique cultural identities result from the historical circumstances of a people. It is not, on the collective level, what a groupchooses. It results essentially from group historical experiences and situations. Therefore, the correct question in relation to minorityrights law is not, why can’t we all be the same—we are essentially the same—it’s why should one people be oppressed because of itsdifference from another group? The minority rights answer is: they shouldn’t, and therefore they must be afforded the rights required tobe equal.

A group’s ethnic identity is made up of the common experience of their families, their ancestors, and their communities. It concernstheir social beliefs and religious practices, their values, their goals, their way of doing things. It means their music, their way of dress,their hair-styles, their marriage mores, their languages as well as their way of talking, their interests, their particular talents, their cooking,their dance, their sports and entertainment, their treatment of children and the elderly, and so on. These aren’t attributes that people“put on,” in the way that people are sometimes said to “become cultured.” These are attributes that people take in with their mother’smilk, from the historical practice and customs of their community. They provide the fabric for daily life.

Frequently an ethnic identity can be impoverished by oppression. Various expressions of that identity can be devalued by anotherethny which has the power to enforce its values. The instance where African-American corn-row hair-styles were once rejected asunsuitable for those working in Anglo-American-controlled banks is a case in point. The denigration and suppression of an ethnic orcultural expression previously accepted as natural can only have a negative effect on inter-cultural relations.

Groups are different, and they have the right to have their differences recognized and respected as much as their sameness. These differences don’t go away by ignoring them. Rather, ignoring the ethnic dimension of an individual’s identity (while at the sametime accepting majority ethnic identity as somehow “universal”) puts minority groups at a disadvantage, since it prevents the society frombeing able to adequately process their unique demands, needs and requirements for equal status.

QUESTION: What if the minority doesn’t express the desire to maintain its culture, but sometimes seems to be trying toescape from it and assimilate into the majority?

The fact that an oppressed minority is usually afraid to express its unique culture where an environment hostile to the culture ismaintained by the state, is well understood in international law, and is the chief reason for promoting minority rights. African-Americans,like nationalities, have throughout their history affirmed a strong desire to maintain their culture in every way except where it was fearedthat doing so would provoke retaliation from the Anglo-Americans who controlled the apparatus of the state.More often, the minority is simply forced to find means of accommodating the majority culture while at the same time rejecting it. In orderto survive and function in situations where the majority has control and enforces its cultural preferences: in the workplace, in housing, insocial services, in educational institutions, and other areas. For instances, many African-Americans provide an official and unofficialname to their children.

QUESTION: What if the individual minority member wants to assimilate, or join the dominant culture?

We should stress that it remains a feature of minority rights that the individual minority member should not be forced to availhim/herself of the rights he/she might bear as a minority individual, and should be regarded as free to assimilate into the dominantculture, if so desired, and to participate in it fully, without discrimination. However, this decision of the individual does not affect the rightof the group. The individual is simply deciding to be a part of one group and not the other, or both, if the circumstances permit. Minorityrights are not to be taken as enforced ghettoization of minority members.

It should be reiterated that the desirability of assimilating into the dominant culture is often simply due to the dominant culture’spower in the society, and the fact that it has refused to share power with the other nationalities (minorities) and has denigrated theirculture and traditions. Were the minority to achieve equal status through the exercise of minority rights, then minority traditions, values,standards of beauty, etc. would have equal appeal to that of the majority.

QUESTION: You said earlier that minority rights can mean that minorities have the right to control socio-economic andcultural institutions. Give me an example.

Let’s take education. Since Brown v. Board of Education as well as during segregation, African-Americans have been integratedinto the Anglo-American education system. In practice this has meant the demise, at a remarkable pace, of colleges which traditionallyhave served the African-American population. On the other hand, African-American students have not felt at home in Anglo-American-dominated institutions. They have not felt that these institutions adequately represented their history, their interests or their needs. Inshort they did not feel these institutions were “theirs,” in the same way as Anglo-American students might. Many felt embarrassed by theexistence of affirmative action programs, the claimed intention of which was to accelerate their entrance into the Anglo-Americaninstitutions and thereby their assimilation into Anglo-American culture, but which often were administered and interpreted in such amanner as to discredit their true capabilities or to catapult them, under intense scrutiny, into a situation of hostile and unfair competition. Applying the minority rights argument, there could be African-American and Anglo-American educational institutions as well as bi-culturalinstitutions. All would of course be multi-racial.

QUESTION: Does self-determination mean we could control our own school? Re-establish African-American colleges? Thatsounds like going back to segregation. We heard “separate but equal” before but it was never equal. Why should webelieve in it now?

Yes, self-determination might entail African-American control of college curricula, programs and financing. But this wouldn’t be likereturning to segregation. For one thing, there would be no restrictions based on race. Those African-Americans who wished to attendAnglo-American or bi-cultural institutions would be free to do so. Anglo-Americans who wished to attend African-American or bi-culturalinstitutions would also be free to do so. But this time, unlike during either the segregation or the civil rights period, the control of theAfrican-American educational situation would be in African-American hands. This would mean, among other things, that African-Americans could decide qualifications for teachers, hiring and firing, curricula, student eligibility and professional licensing standards,disciplinary codes, dress codes, fee scheduling, etc. (albeit with some restrictions resulting from mechanisms which might be put in placefor ensuring parity, where required, with multicultural national standards.) However, in general African-American institutions would not beaccountable to any other agency or administrative oversight outside of the African-American community.

During the period of segregation, while African-Americans did almost all the administration and teaching, African-Americans, inconjunction with the African-American community, did not establish the subjects or content, nor the priorities, nor were they culturally orpolitically free to promote their culture and vision of the world and the U.S. in equal-status with Anglo-Americans, or to affirm their culturalor political preferences, thus creating the intellectual and cultural ethos of their institutions. Also, during the period of segregation,African-American institutions did not have the funding to permit them to function on a par with Anglo-American institutions.

QUESTION: How would African-American colleges be in any better financial condition in a situation of self-determination?

Article 27 of the ICCPR, as amplified by Article 1 of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic,Religious and Linguistic Minorities, requires governments to “create conditions” favorable to the preservation and development ofminority cultures. In practice this has often meant giving minorities jurisdiction over their own schools. The educational sector hashistorically been the most common sector for minorities to exercise their cultural rights. The funding of these educational institutions hasbeen a government responsibility, financed by a share of public moneys, i.e. transfer payments in those situations where minorities werenot also given the right to raise money in the numerous ways that governments do: by power to tax, by licensing fees, etc. (See, forinstance, Articles 41-43 of the Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country, 1979, in Appendix I.) In Canada, the federal structure andprovincial taxation rights thereunder has permitted French Canadians, by means of their control of the Quebec provincial government, todirectly control a sector of the taxation rights accorded to Quebec and secure funding for education institutions and the Desjardinbanking movement.

QUESTION: If African-Americans controlled their own educational system, how would this make a difference?

First of all, it would enable African-Americans both to preserve and develop their unique cultural identities by accepting communitypractices and understandings as normative rather than (at best) “different but all right.” On the higher level, this is not just a matter ofteaching African-American literature or studying African art. It also permits the expression of an African-American perspective on all thevarious disciplines: history, political science, law, sociology, psychology, economics, anthropology, and so on—in the same way that thisnaturally occurs in, say, Canadian, Quebecois, French, and British educational institutions. It creates responsiveness not just to theneeds but also to the views and practices of the African-American community, seeking to affirm, substantiate and empower these views(both intellectually and in actuality). As such, it would serve as a cornerstone and pillar establishing and ensuring the unique African-American intellectual contribution to global scholarship.

Secondly, it would mean jobs for the community—not just jobs in the present (teaching and administrative positions) but also theguarantee of jobs in the future, for the students coming up, since education as well as professional and other licensing authority could begeared towards meeting community needs.

QUESTION: Since “integration” and the significant movements of whites into traditionally black schools and colleges, manyAfrican-Americans have wanted to set up schools to preserve their own culture. But then they thought: what was the usein establishing schools, if non-discrimination meant they were obliged to open their doors to whites, who might come inand take over. Could they have a policy saying no whites were allowed to come?

It isn’t a matter of the presence of the whites or any other race, it’s a matter of establishing the purpose and curricula of the schoolin relation to the highest African-American standards and needs. All people should be invited to assist a worthwhile purpose. Thecurricula and policies would be dominated by universal values as understood by the African-American community, as well as coursesspecifically geared to meet the needs of the African-American community.

QUESTION: Does African-American control of the educational system mean that kids would be learning Afrocentrism?

What African-American control of African-American education means is just that: control of schools by the African-Americancommunity. It’s not simply a question of the curriculum, it’s a question of the administration, philosophy, world view, etc. it will be thedemocratic consensus of the community which decides those qualified to determine what goes into the African-American curriculum.

African culture inhabits African-American culture like the sap, the tree. Whether consciously rediscovered, or simply passed on as family practice from one generation to the next it is pervasive throughout African-Americans’ daily habits, ways of thought and belief,modes of relating, political and lifestyle preferences, and so on. For generations it has represented their heritage and their aspirations. There is no way for the two to be torn apart. And yet, with the centuries of life in America, the African-Americans have evolved tobecome a new African people in North America—Africans who are also American, and whose relation with Europe is significantly differentfrom that of African or Asian populations. Who is to say how that identity, given its freedom to develop according to its own tastes andabilities, might evolve?

If the African-American community as a whole wants Afrocentrism, then likely it would play a larger role. But there are otherelements in the community as well, wanting other things. Undoubtedly Afrocentrism represents yet another rich channel of African culturepouring into the African-American pot. But insofar as Afrocentrism is (self)-consciously imported, insofar as it can be sensed asrepresenting something other than what the people presently are, then it must be recognized as being a part, not the whole of theAfrican-American culture; as feeding into the hole, enriching it, undoubtedly, but not being it. The whole is what the African-Americanpeople are, today, as they stand, as they remember, as they have forgotten, as they experience subliminally, habitually, and so on. As UNESCO’s World Conference on Cultural Policies in Mexico recently declared:

[Culture] comprises the whole complex of distinctive spiritual material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize asociety or social group. It includes not only the arts and letters, but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being,value systems, traditions and beliefs.

It would be a mistake to assume that African-American control of their own schools would mean that they would have to go out and startbehaving in a way that they were not presently behaving. Unless they wanted to do so. Unless they decided, as a group, to do so. Itwould e similar to taking all the noteworthy English writers, poets, scholars, musicians and exponents of “high culture,” as comprising thewhole of English culture. Where, then, would one find steak and kidney bean pie? Or stiff upper lips?

QUESTION: What could self-determination mean in relation to other jurisdictions such as criminal justice?

It’s well known that the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world in relation to its African-American population—infact, four times the rate of white dominated South Africa. Much of African-Americans’ disproportionately higher rates of incarcerationstem not only from acts deriving from circumstances of poverty and oppression that they endure, but also from the disproportionatetendency of law enforcement to apprehend, convict, harass, intimidate and scapegoat the African-American community. Much alsostems from the exacerbated tensions between law enforcement and enforcement personnel has been a largely unsuccessful attempt tomitigate the poor relations existing between the African-American community and the criminal justice system insofar as such blackpersonnel have not themselves been in control of their working environment, but rather caught up in it like helpless cogs in a machine,forced rather to prove themselves to their environment (the various peer groups and hierarchies within the criminal justice system) thanto their community.

Dr. Roberta Sykes, an eloquent spokeswoman for the Black Aboriginal minority of Australia, made the following observationpertinent to police work in her own community, which suffers similarly high rates of incarceration:

We have to work out methods whereby Blacks can have immediate and profound influence in policy and practice. It is my contention that it does not matter very much what color a police officer is—what matters is who he or she is accountable to.

If African-Americans were enabled to influence the criminal justice system or establish their own criminal justice system insofar as it concerned the African-American community—not just through personnel, hiring, firing and appointments, but through a systematized form of African-American input into criminal law content, policy, behavior codes, sentencing, parole, passage or prioritizing of laws, etc., itis likely that an entirely new relationship between the African-American communities and law enforcement would be achieved. Law enforcement would be seen as it properly should be—as an extension of the community values, needs and understandings, and responsible to it rather than to politicians, absentee property holders or Anglo-American philosophic, socio-economic and political priorities or public opinion. The community would have the freedom to find alternatives to incarceration; to give appropriate consideration to community evaluations to offenders; to give due weight to mitigating socio-economic and cultural factors in relation to crimes and misdemeanors; and to stop harassment by establishing procedures to ensure enforcement responsiveness and responsibility to the community and community evaluation of service and service personnel.

QUESTION: If we want to talk about the African-American community controlling its education and criminal justice systems,etc., don’t we have to talk about how we decide what the African-American community wants?

Yes, African-Americans will need to institutionalize a political and democratic means of accessing African-American demands andneeds. The main question African-Americans need to politically and democratically determine is whether, as a people, they wish toassimilate, or to be empowered, collectively. Their answer to this question determines the direction that they should follow—civil rights orminority rights.

This could be done by holding some form of referendum for African-American voters only, which might draw on the good offices ofthe United Nations to provide the required expertise and legitimacy. There are numerous bodies in the international world concernedwith the establishment of electoral procedures under a wide variety of circumstances; they would have answers to the numeroustechnical questions which would arise in that regard. The required expertise is there, if there is the will and desire to access it.

Also, African-Americans need establish democratic structures or institutions which will provide arenas for policy debates, and theemergence of an African-American-elected leadership responsible to the African-American people. This may mean establishing a national Council, and African-American Congress, and African-American Assembly or whatever, anddemanding its recognition by the government as the only legitimate voice of the African-American people.

QUESTION: What are the advantages of an African-American National Council, Assembly, Congress, or what have you?