The Ghana Tourism Authority predicted its 2019 Year of Return initiative would attract 500,000 extra visitors. Official data from January to September 2019 showed an additional 237,000 visitors - a rise of 45% compared with the same period the previous year. Minister of Tourism Barbara Oteng Gyasi said the Year of Return had injected about $1.9bn (£1.5bn) into the economy. Now, Guinea Bissau is launching its “Decade of Return” Initiative. Will it have the same economic and social impact?

From 1668 to 1843, 126,000 people were shipped from the slave trading port of Bissau on the coast of modern day Guinea Bissau, West Africa to the Americas. Records show that 6,400 people were brought to the Gulf Coast, 10,000 people were brought to the port at Charleston, South Carolina, 4,500 people were brought to Chesapeake, and 1,400 people were brought to New York. On February 23, 2021 Nhima Sissé, Secretary of Tourism of Guinea Bissau officially welcomed the descendants of these people to return to their homeland to officially launch the Guinea Bissau Decade of Return Initiative.

According to Siphiwe Baleka, President of the Balanta B’urassa History & Genealogy Society in America (BBHAGSIA) and the brain behind the Guinea Bissau Decade of Return Initiative,

“From 1761 to 1815, records show that 6,534 Binham Brassa (Balanta people) were trafficked from their homeland and enslaved in the Americas. That’s an average of at least 121 Balanta per year. If you include Baga, Banhun, Biafada, Bijago, Bissau, Cacheu, Cassanga, Floup, Jola, Manjaco, Nalu, Papel, Sape, Bambara, Fula, Gabu, Geba, Jalonke, Mandinka and Mouro, it is estimated that in the United States there are as much as 500,000 people who are descendants of people taken from the ports of Ziguinchor, Cacheu, Bissau, Geba, St. Louis (Senegal). There are even more such people in the Caribbean Islands and in Brazil.”

Baleka believes that the return of these “lost sons and daughters” of Guinea Bissau is exactly what is needed by the people on both sides of the Atlantic.

GUINEA BISSAU

Guinea Bissau is a small country on the West Coast of Africa with just under two million people, ranking it 150th in the world in terms of population. The World Bank starts its country profile for Guinea Bissau by stating, "Guinea-Bissau, one of the world’s poorest and most fragile countries. . . .“ According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Guinea-Bissau's GDP per capita ranks 174th out of 192 nations. The 2019 Human Development Index (HDI) of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ranked Guinea Bissau 178th out of 189 countries. More than two-thirds of the population lives below the poverty line on less than $2 per day. Combined life expectancy for men and women is just 48.7 years. The World Food Program USA estimates that 27.6 percent of the country suffers chronic malnutrition. One in seven children still die before reaching the age of 5 and more than a quarter of all children under 5 are stunted.

With a Gross National Income of US$570, Guinea-Bissau is the 12th poorest country in the world. The economy of Guinea Bissau depends mainly on agriculture; fish, cashew nuts, and ground nuts are its major exports. Cashews account for about 90% of the country's exports and constitute the main source of income for an estimated two-thirds of the country's households. According to the government, around 80% of the rural population work in the cashew harvest.

Guinean economist Aliu Soares Cassama stated, “Our economy has had a deficit in the trade balance for a long time. In other words, we import more and export less. We know that economic agents do not have purchasing power due to the total paralysis of the State, and this situation will further complicate the economic weakness that the country is experiencing.”

When the COVID 19 pandemic hit and the world went into a global lockdown, Guinea Bissau was hit hard. The decision to put the entire population in quarantine led to runaway inflation. There was a food shortage and people could not afford to buy what food there was. The risk of starvation grew daily for as many as 60% to 70% of the people of Guinea Bissau.

“We tried to call the attention of the world, and particularly the United States, to what was happening in Guinea Bissau. We made a humanitarian crisis intervention video and a GoFundMe campaign,” said Baleka. “We even published AN OPEN LETTER TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS, THE CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS, AND THE UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID) pleading with them to send a plane filled with food. Our appeals fell on deaf ears.”

In the end, it was only BBHAGSIA that took any action, raising money and distributing food in nine rural villages in Guinea Bissau. “Guinea Bissau just isn’t on the radar for Americans,” Baleka said.

GUINEA BISSAU AND THE UNITED STATES

The United States does not currently have an Embassy in Guinea Bissau. According the the US Government’s Integrated Strategy for Guinea Bissau,

“the USG can help integrate Guinea Bissau into the greater regional and global economy. . . . The United States has interests in Guinea Bissau despite the country’s small size. . . . In a region susceptible to epidemics, poor public health infrastructure and personnel leave Guinea Bissau vulnerable to emergencies. . . . The lack of a permanent U.S. diplomatic presence in Guinea Bissau constrains the promotion of our interests there. . . .”

For fiscal year 2020, the only US foreign aid to Guinea Bissau was $150,000 from the Bureau of African Affairs for International Military Education and Training.

Nevertheless, on January 29, 2020 the U.S. Ambassador to Senegal and Guinea-Bissau, Tulinabo Salama Mushingi attended the launch of the USDA’s Food for Progress regional cashew value chain project, also called the Linking Infrastructure, Finance, and Farms to Cashews (LIFFT-Cashew). The program implementing a $38 million, six-year project in The Gambia, Senegal, and Guinea-Bissau will enhance the regional cashew value chain to improve the trade of processed cashews in local and international markets. However, this project only reinforces Guinea Bissau’s fundamental problem of mono-crop farming for export. And when the country went into lockdown, it had no effect on helping the people.

ENTER SIPHIWE BALEKA

In 2003, Ras Nathaniel Blake (whose named was legally changed to Siphiwe Baleka in 2008) was working as a journalist in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia covering events at the African Union and the Economic Commission for Africa.

“I started attending meetings with the Ministers of Finance and Planning and studying their proposals to increase capital inflow and reverse the brain drain,” says Baleka. “Some of these African leaders decided that cultural tourism could be a major engine for Economic growth. But their plans were targeting the wrong people and were very wasteful. Missing was outreach to the descendants of people who were trafficked in the criminal European trade of African people. I decided to help the governments truly value and focus on these members of the African diaspora.”

At that time, the repatriated Rastafari community was suffering from immigration issues, even though some of them had been in Ethiopia for more than twenty years. After immigration officials arrived in the Shashemane community to investigate, Baleka followed up by studying Ethiopian citizenship laws. He drafted citizenship recommendations that would recognize the repatriates as “Foreign Nationals of Ethiopian Origin.” (see below) Fourteen years later, Baleka’s recommendations were finally adopted by the Ethiopian government and they issued residence permits, a moment that was celebrated as a major step towards the community's recognition and integration.

Baleka also sent recommendations on behalf of the entire African Diaspora to the African Union and attended the African Union Grand Debate held in Accra, Ghana in 2007.

FIHANKRA AND AKWAABA ANYEMI IN GHANA: A CASE STUDY

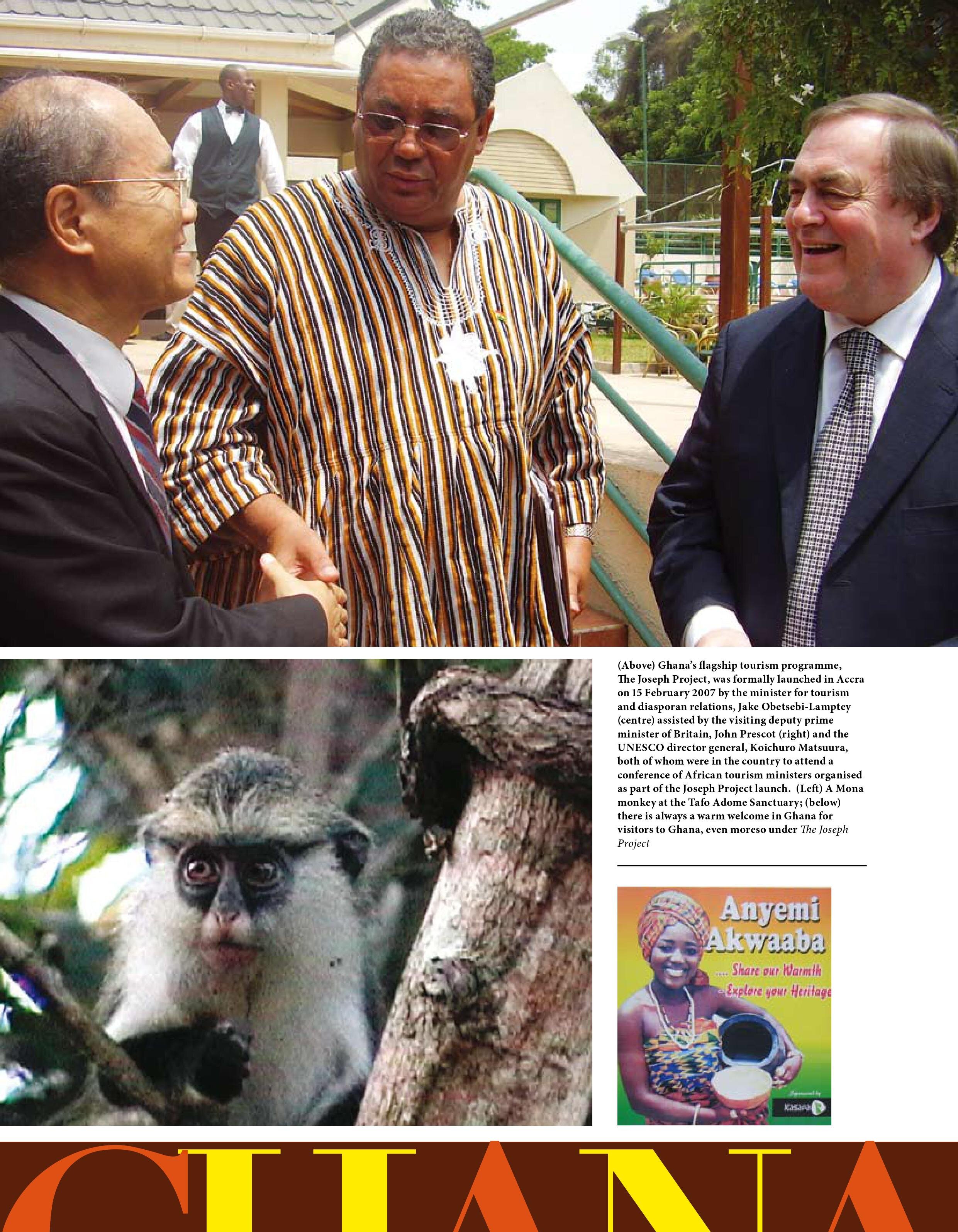

Ghana was one of the countries in 2003 that realized the impact that cultural tourism could have on the country. Jake Obetsebi Lamptey, the country's Minister of Tourism and Diasporan Relations in Ghana at the time, stated,

“We're interested in all the Africans in the Diaspora who were affected by the slave trade. And that includes in North America - not just the United States, but also Canada. It includes the whole of South America - who have big African populations - the whole of the Caribbean, and then those who went through the Western Hemisphere and are now in Europe. . . . Let them come back [to Ghana]. Let them get a taste and say okay, let me see something else about Africa. Let me find out where in Western Africa my people originally came from, and then themselves make the pilgrimages to those places.”

Ghana’s Ministry of Tourism and Diaspora Relations (MOTDR) created a 2003-2007 Strategic Action Programme that aimed at raking in about 4.5 billion dollars by 2007, and was geared towards putting the necessary infrastructures in place to make Ghana a first choice tourist destination. The plan included:

Creation of the Tourism Press Corps (August 2003): A special group of journalists were selected to inform and educate the public on tourism and related issues in Ghana.

Introduction of tourism and hospitality programmes of study in more of Ghana’s tertiary institutions to develop tourism human resource. An example is the Bachelor of Arts Degree Programme (Culture and Tourism) introduced in KNUST (2003).

Introduction of the National Chocolate Day (2006): To promote Ghana’s cocoa and consumption of cocoa products among Ghanaians.

Promotion of tourism to be added to Ghana’s Poverty Reduction Strategy (2005).

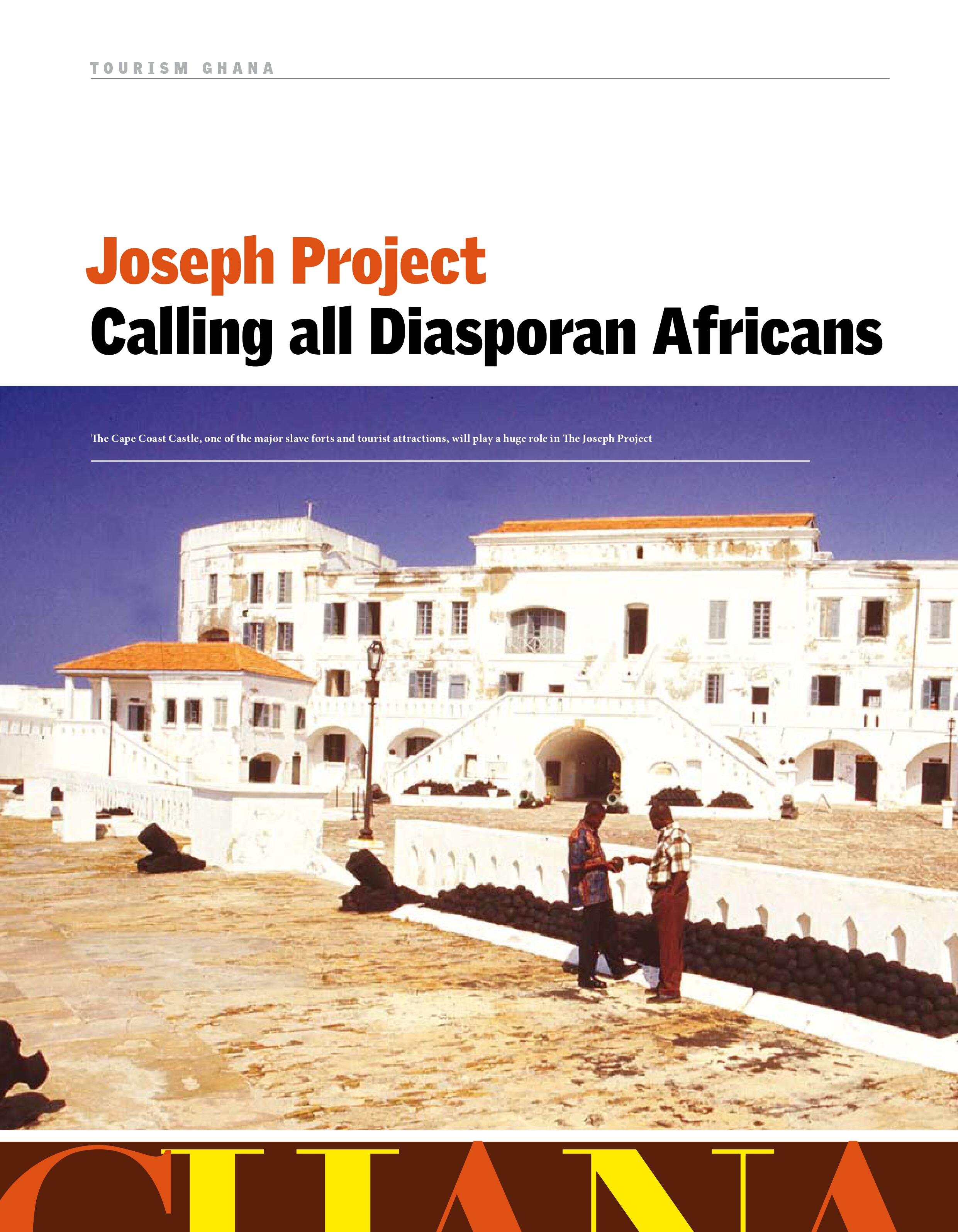

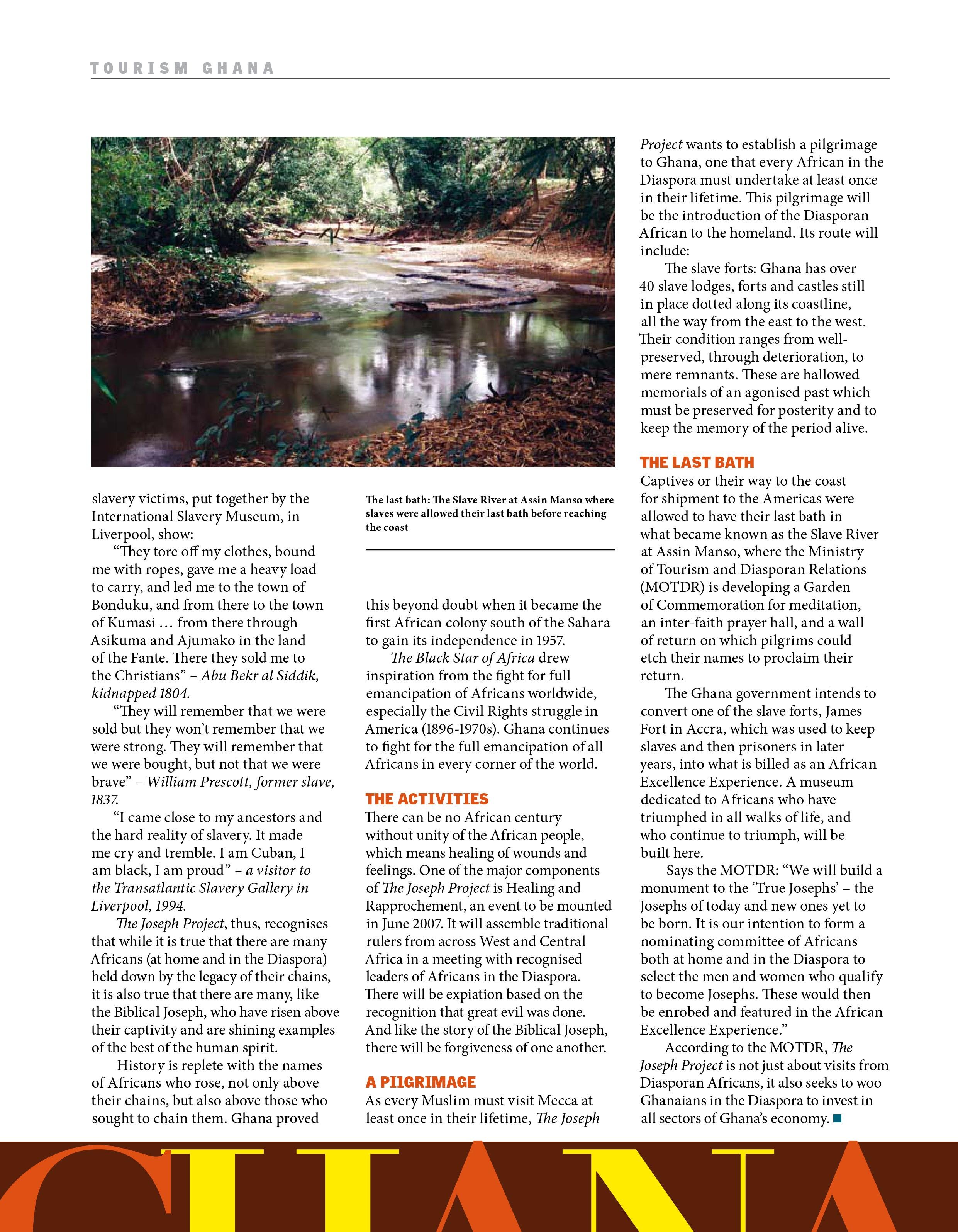

The construction and commissioning of the Assin Manso Slave Mausoleum and Reverential Gardens as Sites of Conscience. As well as the promotion of the Assin Manso Slave Route Project.

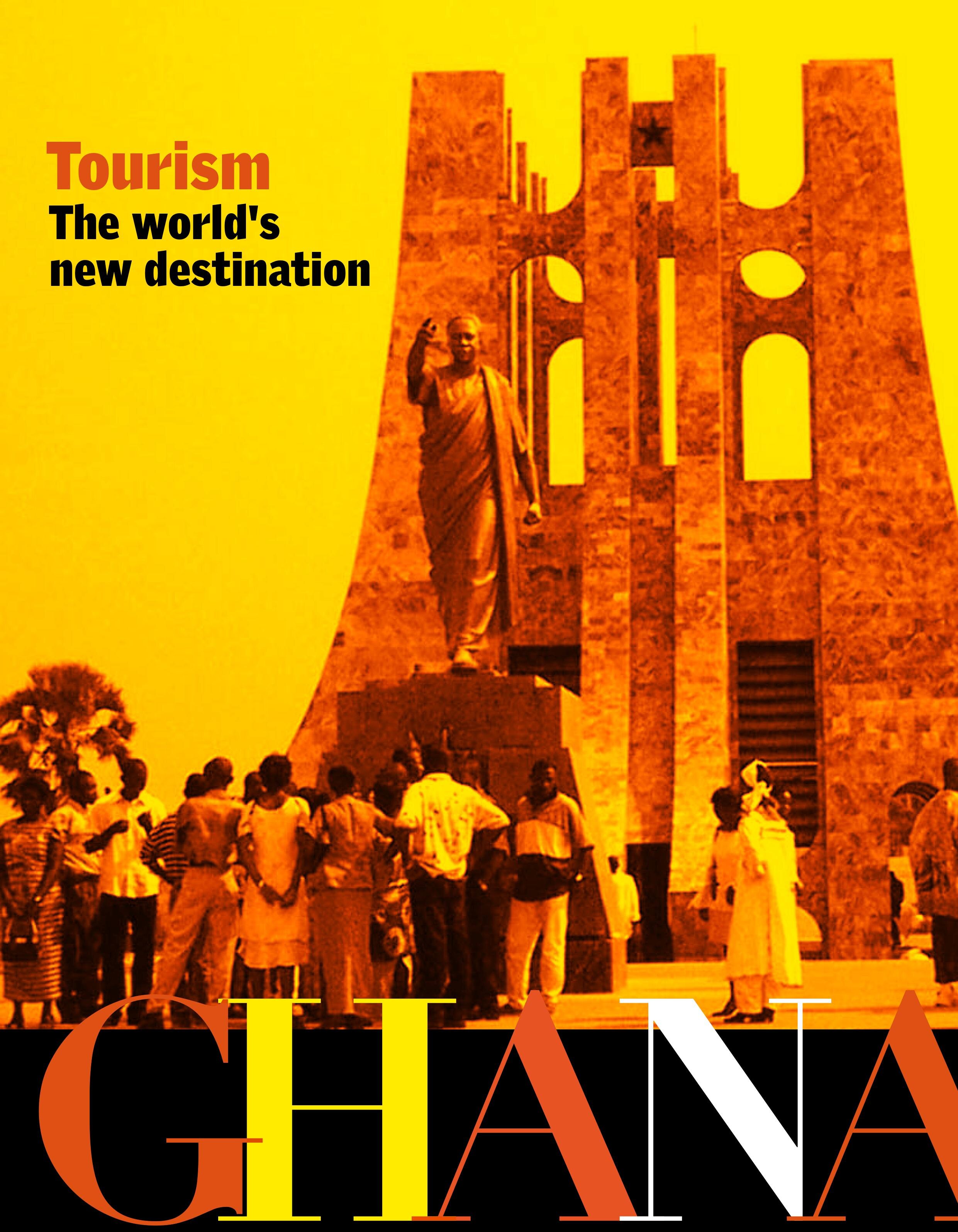

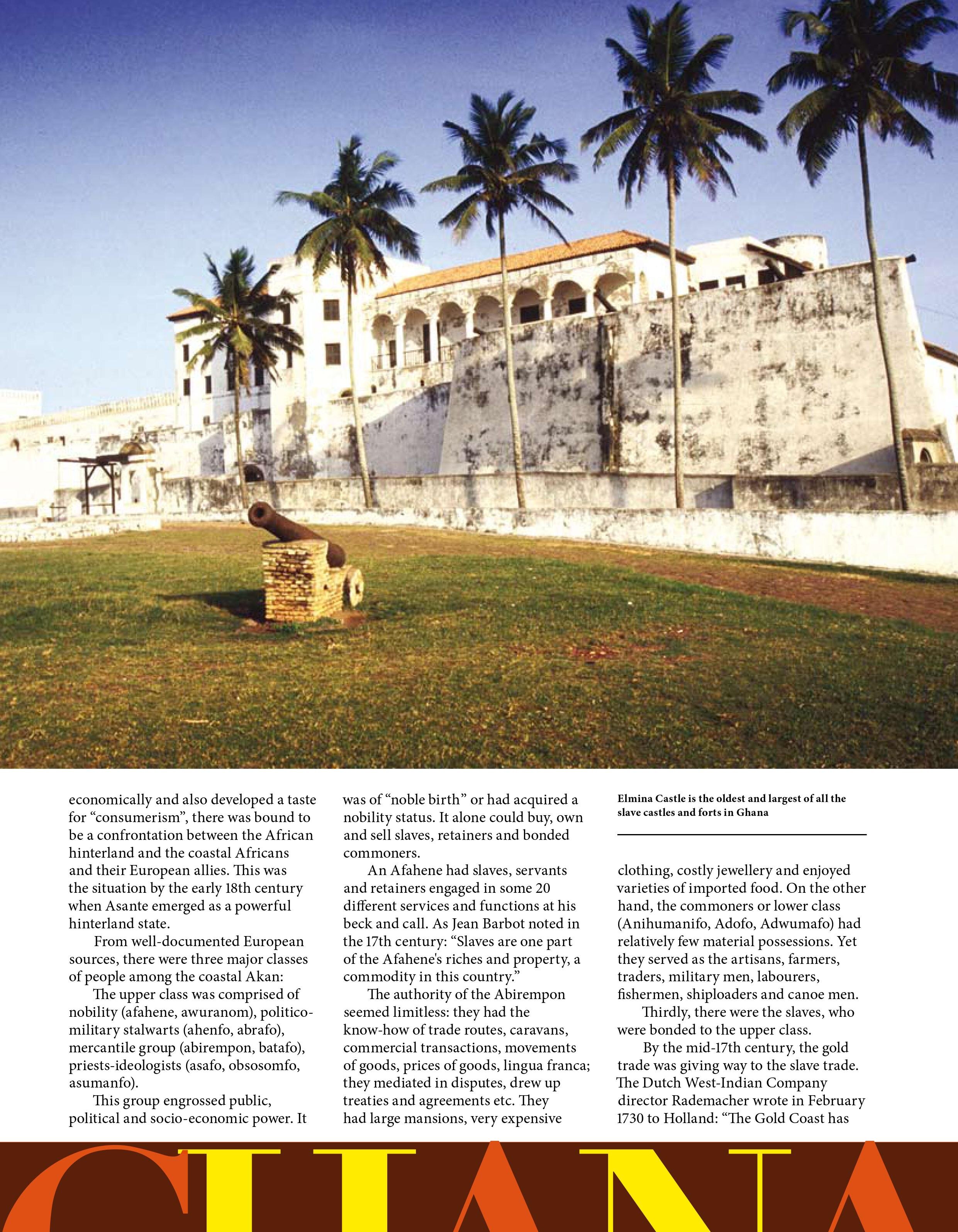

Ghana was ready to launch the Joseph Project in 2007 to coincide with the 200 year anniversary of the British abolition of the slave trade (1807) and the 50 year anniversary of Ghana’s independence (1957). Ghana had already passed their Right to Abode law offering people of African descent the opportunity to settle permanently in Ghana. (Note: many critics, complain, however, that legal technicalities make the process quite complicated.) Ghana created a marketing campaign utilizing the unfortunate data that between 10 and 28 million Africans are believed to have been shipped across the Atlantic between the 15th and 19th centuries from the Elmina Cape Coast Castle dubbed “The Door of No Return”. Ghana used this historical fact, along with the fact that W.E.B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Maya Angelou and other African American celebrities had already visited Ghana to position itself as “The Gateway Back to Africa.” The 2007 Joseph Project was then marketed primarily to Afro-Brittans in England and her Commonwealth territories.

In response to criticism that Ghana was only seeking to get into the pockets of the African Diaspora as a source of revenue, a legitimate claim given the genesis of cultural tourism projects at the Economic Commission for Africa, Minister Lamptey, to his credit, emphasized the essential spiritual purpose of the project,

“With the launch, we're doing - essentially, we're doing a healing process because we feel that we're never going to get people coming together again until and unless we have put the spirits of our ancestors to rest. People are affected by violence, and no greater violence has been visited upon a people than the violence that our people suffered through capture, transportation and then what they suffered in the slavery here and post-slavery, and indeed, in many places where they're still suffering today.

So we want to start with a healing ceremony this year, and the healing ceremony will send a signal to the ancestors that the children and the grandchildren are now beginning the process of coming together.”

Minister Lamptey also highlighted the lack of education and knowledge about what happened to the lost sons and daughters of Africa,

“The Joseph Project, but it's part of a broader program called the Akwaaba Anyemi Program, which is welcome home brother or welcome home sister. And part of it, a major part of it, is teaching our people who the diasporans are. Because the colonials had a situation where - when the slave trade stopped, they drew a veil across it, as if it never happened. In our history books that we were - that our children were taught, there's about three lines about the slave trade, and that's all. You know, what they've been through, the struggles they've been through, we don't know about.”

The Akwamu people in Ghana, did remember, however. They knew that they sold their own brothers and sisters into slavery. The term Fihankra is a Ghanaian expression which means, “When leaving home no goodbyes were said.” Fihankra, then, refers to all Africans from the Diaspora who are descended from the trans-Atlantic slave trade. In December 1994, the Akwamu purified the skin and stool of Fihankra, the physical symbols which were purified to represent the apology given by several Ghanaian elders and the welcoming home of the Diaspora. The Akwamu also gifted land in Yeafa Ogyamu to represent their own personal atonement (for slavery). Promises to develop a fire station, police station, health facility, schools and various businesses were made. By 2006, Fihankra had become a disaster. Unfortunately, the sad history of that Fihankra land grant is a cautionary tale of what happens when economic development is prioritized over human development.

The Joseph Project was re-branded for 2019 as the “Year of Return” in order to commemorate the 400 year anniversary of the arrival of African people in the Jamestown colony in America. Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo came to Washington DC in September of 2018 declaring and formally launching the “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” for Africans in the Diaspora, saying, “We know of the extraordinary achievements and contributions they [Africans in the diaspora] made to the lives of the Americans, and it is important that this symbolic year—400 years later—we commemorate their existence and their sacrifices.” US Congress members Gwen Moore of Wisconsin and Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas, diplomats and leading figures from the African-American community, attended the event. By December, Black Hollywood started its return. Ghanaian-Austrian actor Boris Kodjoe and Ghanaian-American Bozoma Saint John (formerly the Chief Branding Officer at Uber) hosted Christmas parties for an array of celebrities including the supermodel Naomi Campbell and actors Idris Elba and Rosario Dawson. By January, CNN had named Ghana as one of its 19 best places to visit in 2019. Lonely Planet organized a specific Year of Return tour.

By the end of 2019, the Year of Return had seen almost a million tourists, more than double what was expected, an increase of almost 50% from the previous year. US$1.9 billion dollars had been injected in the economy. On November 27, 2019, 126 African Americans and Afro-Caribbean, many of them members of the Rastafari community, were given citizenship.

WHAT ABOUT GUINEA BISSAU?

“I was concerned about my ancestral homeland,” Baleka complained. “Every body was going to Ghana and then to Sierra Leone. People I know were getting citizenship in their ancestral homelands. Ghana was getting all this economic boost and development, and I was thinking, ‘What about Guinea Bissau?’ African Americans don’t even know about Guinea Bissau and the country was missing out on this opportunity. I wanted to help the Government get on board.”

And that’s exactly what Baleka did in January of 2020. He met with the then Secretary of Tourism Catarina Taborda and Secretary of Culture Antonio Spencer Embalo and explained to them a plan to launch Guinea Bissau’s “Decade of Return” Initiative. A great Africa Day 2020 Return to Guinea Bissau event was planned for May 25 to June 2, 2020 but then COVID 19 struck and the event had to be postponed. Meanwhile, a new administration came to power.

According to Baleka, “Things were moving in the right direction. I had given radio and tv interviews in Guinea Bissau explaining the importance of the Decade of Return. The Secretary of Sport, Dionisio Pereira, wrote a letter of invitation to Olympic Legend Jackie Joyner Kersee. Everyone was getting excited and then everything changed. When I went back to Guinea Bissau in December of 2020, I had to start all over again with the new administration.”

Baleka emphasized that Guinea Bissau had its own unique cultural attractions that would be of interest to the African Diaspora people and especially African Americans. “Everyone talks about Ghana’s ‘Door of No Return’. But if want to see where the slave trade started, you have to go to Senegambia - Senegal, Gambia and Guinea Bissau. That’s where the Portuguese came first,” said Baleka.

Baleka also explains that most African Americans know nothing about Amilcar Cabral and the successful liberation struggle waged by the people of Guinea Bissau against their Portuguese Colonizers.

“Cabral was Guinea Bissau’s Malcolm X, except that Cabral successfully liberated the people of Guinea Bissau before he was assassinated. Guinea Bissau achieved independence, not as a neo-colonial grant, but as the result of the courageous armed resistance to the Portuguese. African Americans tried armed resistance to the United States to liberate themselves, but lost and they are still colonized in America today as evidenced by the Black Lives Matter movement for justice. But they can learn a lot and be inspired by Cabral and Guinea Bissau. African Americans can come to Guinea Bissau, visit the Slave Museum at Cacheu, learn about Cabral, experience the cultural diversity of performance groups like Neto de Bandim, and of course, experience the eco-tourism of the Bijagos. But that won’t happen without an effective marketing campaign from the Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Culture of Guinea Bissau.”

A savvy diplomat, Baleka has learned from Ghana’s example the things that they did correctly and also the mistakes that they made, and it seems that, so, too, has the current Secretary of Tourism, Nhima Sissé. To launch the initiative, Secretary Nhima Sissé has invited celebrities of Balanta descent in America including musician Shelia E, Olympic legend Jackie Joyner Kersee, boxing legend Roy Jones Jr., and radio personalities Tom Joyner and Charlamagne tha God, to attend the inaugural events in May and June.

Additionally, Baleka himself is doing his part to draw attention to Guinea Bissau by attempting to compete in the summer Olympics in Tokyo as a member of the Guinea Bissau Olympic Team, a feat that would make him the oldest swimmer in Olympic history. Already, Baleka’s effort has been picked up in the American press by both Sports Illustrated and Access Daily TV.

“People talk about conditions for a perfect storm, “ says Baleka,

“but Guinea Bissau has the conditions for a perfect harvest. There is new momentum in the Back-to-Africa movement. Stevie Wonder is just the latest Black celebrity to express the futility of living dignified lives in America, a sentiment articulated by Derrick Bell, the first tenured Black professor at Harvard Law School in 1992. 750,000 people have taken the African Ancestry DNA and tens of thousands have discovered that their ancestors came from the people of Guinea Bissau. In 2021, Guinea Bissau will have unprecedented positive media attention and publicity. If it can do what Ghana did, and do it better, then it will benefit both the people who are returning and the people of Guinea Bissau. This is an opportunity that Guinea Bissau can not afford to squander.”

Whereas Ghana was focused on courting wealthy members and business owners of the African Diaspora, Baleka believes that that approach is a mistake. “People went to Ghana who had no connection to the people. They didn’t even know if their ancestors were even from Ghana, no effort was made to learn any of the indigenous languages, and few traveled outside the capital and main tourist attractions. How did this help the average Ghanaian, the youth and the people in the rural villages?” asks Baleka.

Reporting on Ghana’s 2019 Year of Return publication, Equal Times wrote,

As a young woman with degrees from American universities, Marie has found making business connections in Ghana quite fruitful. She also notes that there are more opportunities and resources in Ghana than in her country of heritage, Jamaica. But she is aware of the privileges that being an expat affords her.

‘If you’re a local with a high school diploma or even with a college degree, the labour market can be tough. Finding a job or getting compensated at a level that makes sense can be very difficult,’ she says. “However, if you are foreigner...then your privileges are different. You have access to certain opportunities that locals might not. And because there are foreign companies coming in and setting up there might be more of a gap.” Because of this Marie says that she focuses on skills training and hiring locally.

[Akwasi Ababio, director of the Office of the Diaspora and chairperson of the Year of Return committee] says this is something that his office is keeping in mind. He is, however, excited by the possibilities the diaspora can bring to Ghana, through investment and business development. “For any government you would want people to contribute through its flagship programs,” he says, referring to the ‘One District, One Factory’ industrialization initiative, for example, which aims to create as many as 3.2 million jobs by 2022.

The government is currently touting industry-led development with a focus on public private partnerships. But the country still faces huge challenges; with a large youth population and high levels of unemployment and poverty, the government will have to balance the potential that comes with enticing tourists and foreign investment without exacerbating the already entrenched inequality in the country.”

Baleka wants to change that very development model which has shown to breed xenophobia, inequality and corruption going all the way back to the mid 1800’s when slaves and freedmen began returning to Liberia and Sierra Leone. “The only way this is going to work in the long term and bring benefits to everyone, “ said Baleka, “is when people first connect with their ancestral lineage and attempt to integrate into the ethnic group from which they descend first. That is essentially the true meaning of the concept of Reparations. For this to happen, people have to first identify who their ancestor was that survived the middle passage. Where did he or she come from? What group of people did he or she belong to? That’s where you go because that is the requirement for connecting with ancestors and putting that spirit to rest that was traumatized by the slave experience. You have to go to the origin of that and connect with THAT ancestor specifically.”

Baleka is trying to set a personal example by establishing the Balanta B’urassa History & Genealogy Society in America and providing language training for its members who will be attending the inaugural event. And the micro development projects have already begun. Not only have the members distributed food in nine villages, they have raised money to help a family establish a guest house so that tourists can have a more authentic experience with the people and spend their tourist money in ways that help the people directly instead of going into the pockets of the foreigners who own the hotels. Baleka plans to use the renovated guest house to serve as his training camp in Guinea Bissau before the Olympics. “I realized I could spend $4,000 to stay in a hotel or I could give that same $4,000 to this family who shares my ancestry, so that they could start a bed and breakfast business,” Baleka added. “This is a better development model. It’s people to people who share the same ancestry and have a blood bond.”

Baleka says that Guinea Bissau must look at this long term. There isn’t going to be anything like the number of tourists that Ghana saw. But a successful event this year will put Guinea Bissau on the map, just like Ghana’s Joseph Project in 2007 paved the way for its massively successful 2019 Year of Return. According to the World Bank, international tourism receipts are expenditures by international inbound visitors, including payments to national carriers for international transport. These receipts include any other prepayment made for goods or services received in the destination country. They also may include receipts from same-day visitors, except when these are important enough to justify separate classification. Guinea Bissau’s tourism receipts in 2018 totaled just US $20 million and represents just 5.26% of its exports. By contrast, Ghana’s tourism receipts were $996 million in the same year. Neighboring Gambia saw $168 million in tourist receipts.

Baleka believes that Guinea Bissau needs to set goals and come up with a plan. “Within ten years,” he says, “they could be the gold star, flagship example for the new model of development and cultural tourism in Africa and for small, underdeveloped countries everywhere.”

Siphiwe Baleka’s Citizenship Recommendations to the Government of Ethiopia in 2003

DATA ON THE SLAVE TRADE FROM GUINEA BISSAU

From Africa to Brazil: Culture Identity, and an Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1830 by Walter Hawthorne