Excerpts from REPARATIONS YES! A Suggestion Toward the Framework of a Reparations Demand and A Set of Legal Underpinnings

by

Imari Abubakari Obadele, Chairperson, The People’s Center Council (National Legislature) of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika, September 1987

“The central proposition of this paper and the draft bill for reparations which is annexed hereto is that our enslavement in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States was a matter of war - war conducted against Afrika under authority, initially, of the British government and the legislatures of the Thirteen Colonies and ultimately under authority of Clasue One, Section 9 of the First Article of the United States Constitution.

[Clause One, Secion 9, Article One, states: “The Migration or Importation of Such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each person.”]

It was war conducted against Afrikan people - who grew into a nation, an oppressed nation, between 1660 and 1860 - within the United States under British and Colonial authority and, ultimately, the authority of Clasue Three, Section Two of Article Four of the U.S. Constitution.

[Clause Three, Section 2, Article Four, states: “No person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”]

The conditions of our degradation, a subordinated and exploited people denied liberty by force, are too well known to be re-documented or chronicled here. Justice Harlan, writing his dissent in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, at 29, said that the provisions of the 1850 ‘Fugitive Slave Act…. placed at the disposal of the master seeking to recover his fugitive slace, substantially the whole power of the nation.’ The U.S. Army under Andrew Jackson destroyed the New Afrikan states in Florida. Militia and White civilians carried war to all our communities in the woods. The U.S. military and White civilians put down the attempts of first, Gabriel Prosser and then Denmark Vesey and John Brown and Osborne Anderson to seize land and build New Afrikan states. For these state-builders the U.S. courts authorized bloody executions, corporal punishment, and transportation beyond U.S. shorees. . . .

It is the position of this paper, embracing propositions enunciated by the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika sixteen years ago, that the United States conducted war against the New Afrikan nation on this land throughout the era of slavery, that the war was authorized by the United States constitution and carried out in aggressive military actions against the efforts of our people to seek freedom individually and to build New Afrikan states collectively, by the United States government itself, by the various State Governments and by civilians mobilized against the New Afrikan People and nation.

It is the proposition of this paper that reparations must be part of a general settlement of the war which the United States has waged against us.

In keeping with settlements consummated at the end of World War I and World War II, and with the precedents in International Law created by these settlements, the settlement for New Afrikan people must include not simply money reparations but exercise of the freed and informed right to self determination by our people, and the release of our militants, soldiers, prisoners of war, now in U.S. jails, who were taken in defense of our nation against the United States.

In summary, the money damages are due, of coure, for labor stolen from our forebears, for cultural assault, and for unjust war, with accumulated interest. But the money portion of our reparations must be a significant contribution toward rehabilitation: repatriation for those who wish and can achieve citizenship in an Afrikan state, rehabilitation of the New Afrikan states and incipient states, and their successors, destroyed on this soil during the war which was slavery and afterwards. There must be reparation payments for rehabilitation of us as a people, our social structure in the United States, and culture, in recognition of the design followed in the United States to make us into a race of ignorant subservients, unable to revolt, and forgetful that We had a duty to do so. . . .

There are reparations due to certain Afrikan states for the war which the United States authorized against them; to us, as well, for our states that were weakened or destroyed in Afrika during the course of America’s war there, which resulted in our enslavement.

(A state, with its army, protects the people. People cannot be harmed by outsiders unless the army is destroyed, rendered ineffective, or co-opted) And it is also tru that discussions must be held with Nigeria and other states on reparations for us. These could involve not simply trade arrangements but substantial political and diplomatic assistance for those of us who want indpendent statehood.

Those discussions ar separate, however, from the claims against the United States - and the subject of this paper.

The precedents for the claims described above are to be found in

1) the agreements which concluded World War I and World War II;

2) the U.S. Supreme Court case, The United States v. The Libellants and Claimants of the Schooner Amistad, 15 Peters 518 (1841);

3) the New International Law Regime, which took rise with the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514, 14 December 1960; and

4) the principles involved in the work of The Indian Claims Commission, Title 25, U.S.C.A., Sections 70 et seq.

With respect to the lapse of time between the United States initial ceasefire agains us (The Thirteenth Amendment of December 1865) and Queen Mother Moore’s proffer of the Ethiopian Women’s complaint against the United States and petition for reparations to the United Nations in 1965, three comments are particularly appropriate. First, Queen Mother Moore’s efforts were not a beginning; at no substantial period during the era since slavery have our people neglected wholly the campaign for reparations. Second, it has been the power of the United States and its refusal to consider reparations for New Afrikans which has frustrated our efforts heretofore, not any failure on our part to pursue these demands. . . .

WAS IT WAR AND DO WE HAVE SELF-DETERMINATION RIGHTS?

Two essential questions should be addressed. First, was it war? Second, do New Afrikans have self-determination rights? Also implicated is the question as to whether New Afrikans in the United States constitute a ‘nation.’ We turn now to the first question.

In general, ‘war” has been traditionally of two types, conflicts between states, which are governed by international law and practice, and civil wars, in which part of a state contends for sovereignty over territory claimed by the parent- state. Lately, conflicts of liberation movements, including conflicts like that in South Afrika at the present time, where the liberation forces are unable to place armies openly in the field or to hold and govern territory openly, have gained status under the international law. The 1977 Protocol to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, states in Article One:

4. The situations referred to in the preceding paragrah include armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and aliean occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right to self-determination, as enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and the Declaration of Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among states in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

The record is replete with instances of armed conflict and armed suppression of suspected miltants by the United States, during and after slavery. Moreover, the general conditions of slavery make clear also that We were subject during the slavery era to ‘colonial domination and alien occupation.’ . . .

Professor von Glahn notes that ‘a British report in 1870 showed that between 1700 and 1870, a total of 107 conflicts had been initiated without the formality of a declaration of war.’ He goes on: ‘The United States, too, has conducted wars without a declaration: an undelcared war with France from 1798 to 1801, the invasion of Florida in 1811 under Generals Jackson and Mathews, the brief Mexican invasion in 1916, the undeclared war with the Soviet Union in 1918-1919, and, of course, the vietnamese conflict from 1947 onward (for the United States, from March 7, 1965, to March 29, 1973).’

The effort of some New Afrikans to form an indpendent state has been an almost continuous effort from the time of our first fights and revolts in this land to the present. . . . If the level of U.S. military attacks against New Afrikans and the New Afrikan nation receded in the period following the Civil War, our colony was nevertheless subject to a racially conscious policing by sheriffs and local police. The army, too, would appear to suprpress us during uprisings such as those in 1919, the 1940s and the 1960s. The reason for the reduction in naked military attacks lay mainly in our resort to parliamentary means of struggle after the Civil War. But there was no abandonment of the drive for independent New Afrikan statehood - nor for the other two objectives toward which some of our people had striven traditionally: (1) full citizenship in the United States, and (2) return to Afrika.

It is relevant to the charge of war agianst the United States that we were still an occupied and oppressed nation in this period between the Civil War and 1968. We were a colony living on territory claimed by the United States, subject until 1968 to a body of legislation and court decisions which defined our subordination to the White nation and facilitated the Whte nation’s economic and cultural exploitation of us, and our social degradation.

Even the Malcomites, who after March 1968 led the struggle for independent statehood and were resolute practitioners of armed self-defense, eventually supported by the Black Liberation Army, pursued a strategy of attempting to organize, peacefully, an independent plebiscite. This parliamentary strategyy was in accordance with the precepts of the New International Law Regime, ushered in by the United Nations’ Declaration On the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, supra, in 1960. When the organizing of the armed, self-defensing cadres of the Provisional Government accelerated in Mississippi in 1971, however, the United States turned to its military option. At dawn on Wednesday, August 18, 1971, a force of FBI agents and Jackson city police, accompanied by an armored truck, attacked the official RNA Provisional Government Residence. They shot it up and then charged the seven occupants of the house, along with the four who had spent the night at the office several blocks away, with murder of the police lieutenant who died in the attack and with assault of the FBI agent and the policeman who were wounded. In the fall of 1981 the United States brought massive military force to bear in McComb County, Mississippi, to arrest Sister Fulani Sunni Ali, a longtime RNA officer, who was quietly conductin a summer camp for children in the country. The pretext was the New York Brinks incident, during which Black Liberation Army members were implicated, some arrested and some jailed, and one murdered in cold blood by the police as he lay helpless on the ground.

If it is possible to argue that the form of the war against us cahanged after the Civil War, from military activity to occupation duties, the United States kept the military sanction always ready - and, from time to time, used it.

The question was land. The United States Government, unable to export us en masse after the Civil War, was not especially concerned that U.S. policies had fueled our growth as a separate people - giving us our own perspective and history and common gene pool, raising up, between 1660 and 1860, a vastly numbered New Afrikan nation on this soil. Our status as a nation, despite our numbers, posed little more problem for the United States than the many Indian nations - so long as We did not focus overly on our separateness and nationhood, and so long as We did not seriously act for statehood, for sovereignty over land.

The international law, in our era before 1960, was shaped by Europeans and their conquests. This included the question of sovereignty over land, national title to land. And the law was clear. For instance, the principle of prescription sitll means that a state may acquire title over land originally belonging to another state, by occupation over a long period of time. How long is a ‘long’ time? There seems to be no generally accepted international standard. One U.S. court decision, dealing with awards to Indian states, determined that title to land could be recognized for a group which had occupied it ininterruptedly for 50 years. The United States’ objective with respect to the RNA Provisional Government (PG-RNA) was to prevent undisturbed occupation for any period of time.

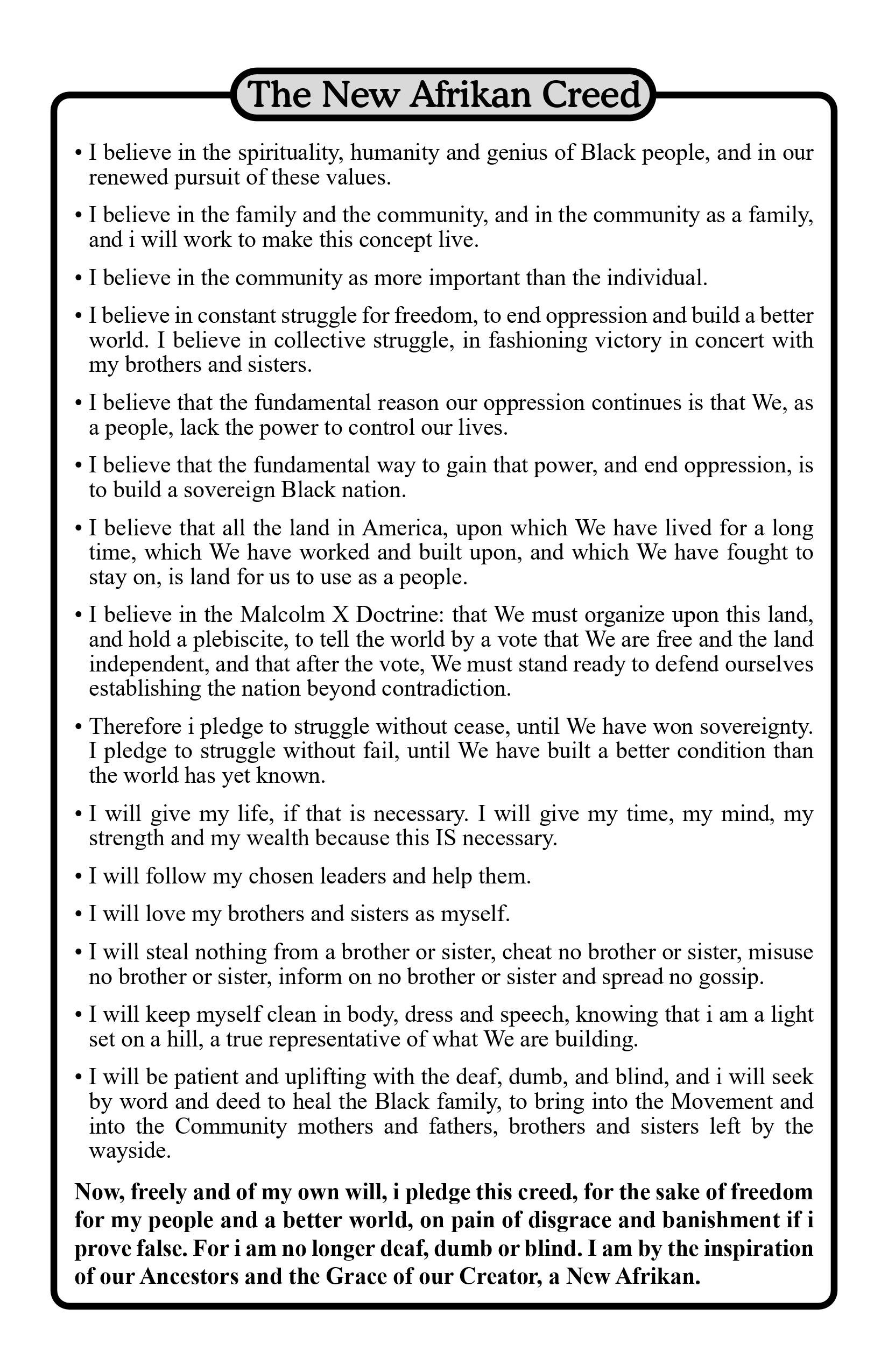

There is little doubt that the United States realized that a form of the prescription principle is embedded in the New Afrikan Creed, which today is part of the Republic’s constitution, the Code of Umoja, and which is recired by gathered Provisional Government cadre at meetings and all imporant occasions. ‘I believe,’ runs the paragraph from the Creed, ‘that all the land in America, upon which We have lived for a long time, which We have worked and build upon, and which We have fought to stay on, is land that belongs to us as a people.’ . . . There is little doubt that the United States understoon that the PG was acting upon this principle in Mississippi.

The partiuclar problem for the United States was that the Provisional Government had been created at a founding convention and then regularly elected, by popular vote since 1975. Although the voting has always taken place in several cities, the totals. so far, have always been small - the largest being 5,000 votes cast in 1975. But the fact of the vote and the potential for it becoming a widespread institution among New Afrikan people, despite the perpetual press ‘white-out’ of New Afrikan activities, posed and pose a serious problem for United States policy-makers. To begin with, the United States is a party to the 1933 Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, done at Montevideo, Uruguay. This convention’s definition of the ‘state’ is in fact the definition which has entered into the principles of United States law, repeated in numerous contexts. Article one of the convention states:

‘The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territtory; (c) government; and (d) the capacity to enter into relations with the other states.’ [Siphiwe note: here is the rationale for having a strong and effective Ministry of Foreign Affairs within the PG-RNA].

The Provisional Government was (and is) a democratically elected government; it was voted for in Mississippi, which testified to representation of a permanent population, and it carried on various nascent forms of relations with China and Cuba (and, in the days since the Mississippi effort of the 1970s, is continuing to broaden these relations with other states). What was lacking, then, to convert this state-building entity, the Provisional Government, into a state was uninterrupted possession of land. [Siphiwe note: now, after almost 58 years, what formal relations or support does the PG-RNA have with other governments? What presence does it have as an observer to the African Union or United Nations? What diplomatic communications history does it have with other states? This is the missing element today that a strong and visionary Ministry of Foreign Affairs can correct.]

The United States’ attack on the Provisional Government in Mississippi and the subsequent major de-stabilization of the Provisional Government by the jailing of some of its leaders and a continuation of the FBI’s disinformation campaign (the COINTELPRO) were simply consistent with the attacks in former days on Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, John Brown, and Osborne Perry Anderson, the New Afrikan states in Florida, and the state of Tunis Campbell. The rationale was simple and obvious: the United States . . . was not prepared to abide the creation of an independent New Afrikan state in North America. Thus, the attacks, the recurrent hot war.

But there was a difference in the international law regime under which the military actions against the New Afrikan states and state-builders before 1960 were carried out and the international law regime under which U.S. military attacks against the Provisional Government were carried out after 1960. The Decolonization Declaration (U.N. General Assembly Res. 1514) said, simply, that ‘All peoples have the right to self-determination; . . . .’ This language has been carried over into the human rights conventions. It was a victory of the Afro-Asian bloc in the General Assembly, achieving numerical prominence for the first time in 1960, and it marked a revolution in the international law. The Declaration states also:

‘4. All armed action or repressive measures of all kinds directed against dependent peoples shall cease in order to enable them to exercise peacefully and freely their right to complete independence…’

Therefore the international law that counted had been written and accepted by the United States and European powers. It served the ratification of their conquests of the rest of the world and codified practices which they had found to be mutually convenient. The Versailles Treaty of 1920, ending World War I, joins the Berlin Treaty of 1885, as a leading statement of the international law as the White and powerful states of the world saw it and enforced it. This document provided for our degradation: it left the Afrikan and Asian colonies of the world War I victors in place and, instead of freeing those held by the defeated Germany, gave our hapless countries and peoples to the mandated ‘care’ of Britain, France and Belgium - at the same time that this treaty was concretizing self-determination as a right for Czechs and Poles and several other people in Europe.

The Afro-Asians in 1960, with the assistance of Canada and a few other states, re-wrote the international law. From that point, not only Europeans but all peoples had a right to self-determination. A subsequent, relatively rapid development of the new law followed. The Principle of self-determination was incorporated in United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2625, The Declaration on Principles of International Law, on 24 October 1970.

The United States abstained from voting on the 1960 Declaration, objecting to the word ‘independence’ in the title, arguing that independence was not the only possible result of an act of self-determination by a people. This was true but irrelevant. Neverheless, the United States Representative, James J. Wadsworth, speaking to a plenary session of the U.N. General Assembly on 6 December 1960 made the following extraordinary remarks - which, of course, under U.S. constitutional principles, are deemed to be the words of the U.S. President and an authoritative statment of international law as the United States sees it:

‘First let me say what we mean by colonialism…. It is the imposition of alien power over a people, usually by force and without the free and formal consent of the governed. It is the perpetuation of that power. It is the deniel of the right of self-determination - whether by suppressing free-expression or by withholding necessary educational, economic, and social development.*** Obviously not all colonial regimes have been the same…. But, however important these differences, the fact remains that colonialism in any form is undesirable. Neither the most benevolent paternalism by a ruling power nor the most grateful acceptance of these benefits by indigenous leaders can meet the test of the charter or satisfy the spirit of this age.

The Declaration on the Principles of International Law in its ‘principle of equal rights and self determination of peoples,’ states, inter-alia:

‘Every State has the duty to promote, through joint and separate action, the realization of the principle of equal rights and self-determination. . . bearing in mind that subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a violation of the principle, as well as a denial of fundamental human rights, and is contrary to the Charter of the United Nations.

The establishment of a sovereign and independent State, the free association or integration with an independent State or the emergence into any other political status freely determined by a people constitute modes of implementing the right of self-determination by that people.’ . . .

To sum up, I have argued here that the United States has waged war against us, as individuals and as a nation. (I have deferred the question of whether We are a nation under international law.) My central and underlying point is that our reparations, based upon slavery claims, are best presented in the context of the United States’ having denied us the exercise of our right to self-determination.

This is because the most fruitful precedents for our reparations claims are those which have arisen out of the reparations payments and the self-determination arrangements made in settlement of World War I and World War Ii. It is also because the fact is the United States did wage a most heinous war against us.

In appraiding the situation of New Afrikans in the United States it is important to keep in mind that We have, almost from the beginning, followed simultaneously three - not one - strategies of struggle. (This is to say that simultaneously some of us have followed each of the strategies.) Those strategies have been, first, a return to Afrika (Paul Cuffee through Garvey to the Hebrew Israelites); second, to change the United States and join it as full citizens (Richard Allen through Frederick Douglass to Marin Luther King), and, third, to build an independent state on land claimed in North America by the United States (Gabriel Prosser through Tunys Campbell to Malcolm X and the Provisional Government -RNA). Throughout our three hundred years of struggle on this soil We have, from at least 1660, been evolving into and have become a Black Nation, a New Afrikan nation, even with the simultaneous pursuit of three strategies. . . .

For clarity on the difference between ‘nation’ and ‘state’ it is perhaps helpful to call on Professor Robin Alison Remington in her discussion of Yugoslavia. She writes: “A country is the piece of real estate occupied by the state. Neither a country nor a state is a ‘nation.’ Rather, a ‘nation’ is a group of individuals united by common bonds of historical development, language, religion, and their self-perceived collective identity.*** According to the 1971 census, the Yugoslav population is 20.5 million, including five official ‘nations’ and a variety of nationalities. The nations are the Serbs, 8.4 million; Croats, 4.8 million; Slovens, 1.7 million; Macedonians, 1.2 million; and Montenegrins, 608 thousand.’

Elsewhere I have made a contribution toward (I hope) clarity.

‘People live in states. The United States is a state; all the fifty states make one United States, and in international law the entire United States (with its 50 constituent states) is known as a state. A state has people land and government. The government, acting for the state, protects the people and the land from outside attack by means of diplomacy and its army; government controls conflict among its own people by education and indoctrination and by means of law, courts, and the police. The government, representing the state, has final control over the lives of people. Only the state, through its government, can lawfully jail people or kill people - either by executing them or sending people to war.

But people come before states. This is to say that nations exist before states. States are created to protect nations. For, a nation is the people and their beliefs and their perspective (their way of looking at themselves and the world) and their way of life - their social structure and their economic struacture. These have arisn out of a people’s own special history, over time. States can be created suddenly, by declaration, by new constitutions, by military coups and successful revolution and by treaty. But nations can only be created by time: nations are people brought together by common history and common mission and common struggle, cemented by common values and a common way of life, on a given land mass, over time. Nations must evolve. They come into being by growing over decades.

The United States began as a white nation, a new English nation, which grew up between 1607 and 1776 in a land away from England. In England the people were having a different experience and history than the English in America. In America the Whites, led by the English, fought Indians and Afrikans for that in which they, the Whites, believed: they believed in the superiority of Whites over Indians and Afrikans and the righ of Whites to take all the land and oppress and exploint Afrikans and Indians.

These Americans, the Whites, built a state, a Republic, to protect the American nation. They did not build this state to protect Indians or Afrikans; in fact, it was built to help Whites better oppress and exploit Indians and Afrikans. It was built to protect the white nation.

Meanwhile, We, the Afrikans, were forming into a new nation also, a new Afrikan nation. This happened between 1660, when the English in America decided definitely to hold us in slavery, and 1865, when our work and sacrifice in the Civil War brought an ende to slavery. In those two hundred years We who had come from different nations in Afrika, where our states had been weakened or defeated altogether, fused into a new people, a new Afrikan people. Struggle against the oppression of the White nation in North America, the United States, fused us. Over the course of 20 decades.’ . . .

So the proposition of this paper and the annexed draft reparations legislation is that the United States waged long, cruel, and unjust war against us as a nation, and for that there is responsibility. . . .

Today the New Afrikan nation, still pursuing simultaneously its three strategies of struggle, has no victorious armies to compel compliance, only the international law - and the strength and ingenuity of the uses to which We and our allies may put the politics of the American state. . . .

In brief, the terms of the attached draft legislation reflect practices which are not unknown to the United States and other states which particpated in or observed the arrangement which followed the two world wars. The plan would provide reparations to the state-building Provisional Government but reparations would go, as well, to individuals and to organized, serving community groups. . . .

As a teacher of young people, I am also convinced that part of the strategy must be to alter the textbooks and our conventions in teaching the American experience - and to alter kindred conventions in movies and literature - so that Americans and New Afrikans, living now, may come to a deep appreciation of the nature of the war waged against us and Indians in America and of the military occupation We have suffered here, as well as the creative, persistent, courageous, and often brilliant struggle Indians and New Afrikans have waged in response.

In the end, history makes clear that to win reparations We must be prepared to take this righteous struggle into the streets. We must be prepared to stop all the machinery of America, if need be, until the just debt of reparations is paid.

FREE THE LAND!”