Guinea: Phases of Portuguese Activity by Amilcar Cabral

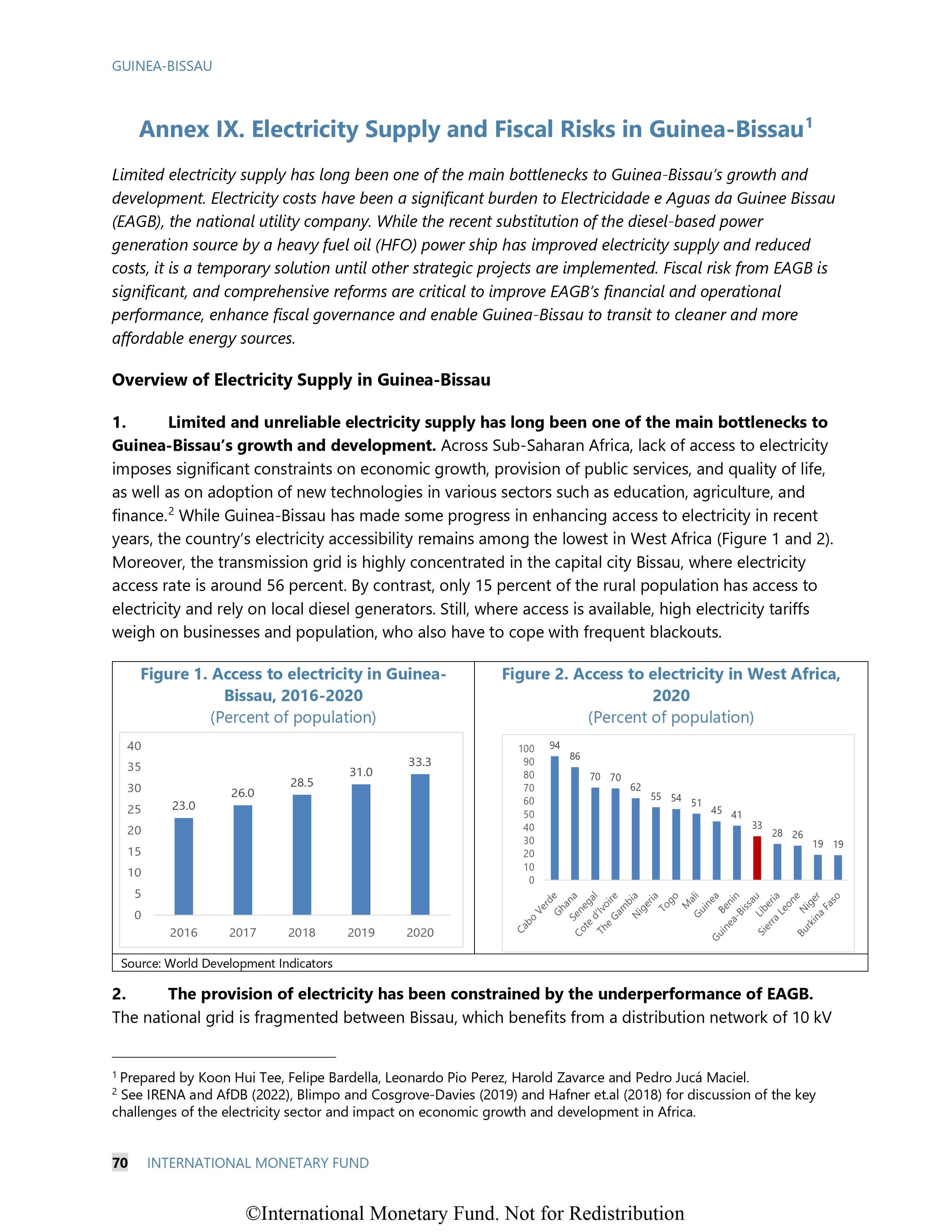

From a declaration made by the Secretary-General of the PAIGC to the UN's Special Committee On Territories Under Portuguese Administration, June 1962. Translated from French.

“It is necessary to emphasize that the economic activity of the Portuguese in Guinea has been for over 500 years, and still is today, almost exclusively commercial. In its development one may distinguish the following phases:

(1) Portuguese monopoly of commerce (especially that of slaves), at first only sent to European donatorios (plantation owners) on the Cape Verde Islands (up to 1530).

(2) Competition from other foreign countries. Settlement by Portuguese tradesmen. Rise of large Atlantic slaving companies which monopolize commerce (1530-1840).

(3) Gradual abolition of the slave trade. Development of research in local products (peanuts). End of the Portuguese monopoly in favor of German and French enterprises (mainly 1840/80-1932).

(4) Portuguese monopoly of commerce, especially of the export trade and shipping. Decrease of non-Portuguese enterprises, concentration of Portuguese monopoly in a handful of enterprises (since 1932).

There is a constant feature characteristic of all these phases: a redemptive mode of economy, strongly, mono-mercantile. At the beginning, slaves.

Today, peanuts.

Herein we relate certain facts which concern the post-slave trade period, up to the establishment of the present political regime. The gradual, eventually definitive abolition of the slave trade upset and disorganized both the economy of 'Portuguese' Guinea and that of the metropole itself. This fact had important consequences for the political evolution of Portugal.

To resolve these problems, the Portuguese tried other forms of commerce and exploitation by developing above all the redemption of local products or those of neighboring areas, which were exported through the port of Bissau. For this reason, they began the penetration of the interior of the country, where they established trading-posts (factories).

The research on peanuts, begun in Senegal in 1840, helped the economic development of the colony. Small farmers (ponteiros} and non-indigenous merchants stimulated or forced the cultivation of peanuts by the indigenous population. In Bolama and on the shores of the Great River of Buba the peanut cycle had its beginnings and numerous trading-posts were established in these areas. Portuguese capitalism, scarcely existent, could not, however, compete with non-Portuguese capital which attempted (successfully) to penetrate Africa by every possible means. After the Berlin Conference which brought about the first great partition of the Continent, non-Portuguese enterprises, which had already succeeded in establishing themselves in 'Portuguese' Guinea, monopolized both the internal and external commerce of the country. This was part of the tribute that Portuguese colonialism had to pay to foreign capital in order to maintain its 'presence' in Africa.

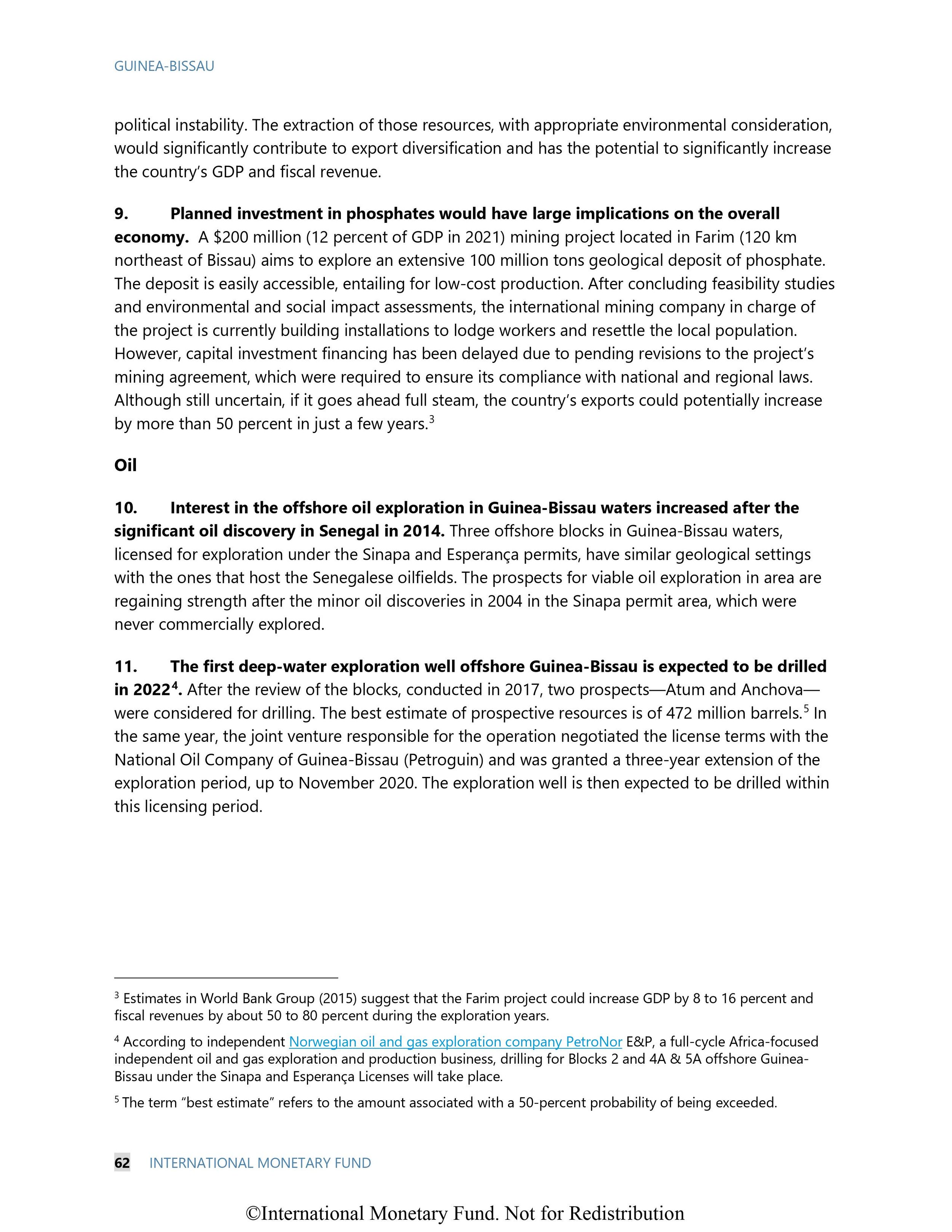

Thus, in 1927 again more than 70% of the exports from 'Portuguese' Guinea were directed to non-Portuguese ports (particularly those of France and Germany), from which an equal proportion of imported merchandise came. We may say that since the end of the last century until the 1930s, 'Portuguese' Guinea was a non-Portuguese colony, administered and defended by the Portuguese.

The development of the peanut crop, which occurred mainly at the beginning of this century, opened up the way to soil erosion in 'Portuguese' Guinea, deeply disturbed the lives of the African peoples, to whom it brought the economic, political and social consequences which characterize the present Portuguese rule. Voluntary in the beginning, the result of prodding, it became the chief preoccupation of the administration and thus came in effect to be a mandatory form of cultivation for the rural Africans.

Defeated by the force of arms, the active resistance of the populations to Portuguese penetration and occupation, the development of a peanut monoculture, along with various subsidiary products (such as palm oil, rubber, leather, etc.) - in a redemptive mode - became the basis of 'Portuguese' Guinea's economy and the determining factor in the political situation of its people within the structure of the Portuguese colonial empire.

It is fitting to emphasize that even the transfer of the capital from Bolama to Bissau had for its principal cause the erosion of the soil on Bolama Island and Buba Region, with the consequent displacement of the peanut cycle on to Bissau Island and the central areas of the country.

The colonialist-nationalism which, in Portugal, brought the present regime to power, did not undo this situation. Quite the contrary, it did every possible thing to reinforce it, for the exclusive advantage of Portuguese interests.

By establishing discriminatory tariffs to protect commerce between the colonies and Portugal, and by guaranteeing to Portuguese ships, among other things, a monopoly of maritime transport between Portugal and the colonies, the present regime laid the basis for the return of the Portuguese monopoly of commerce in Guinea (Art. 228 - 230 in the Organic Charter of the Portuguese Colonial Empire).

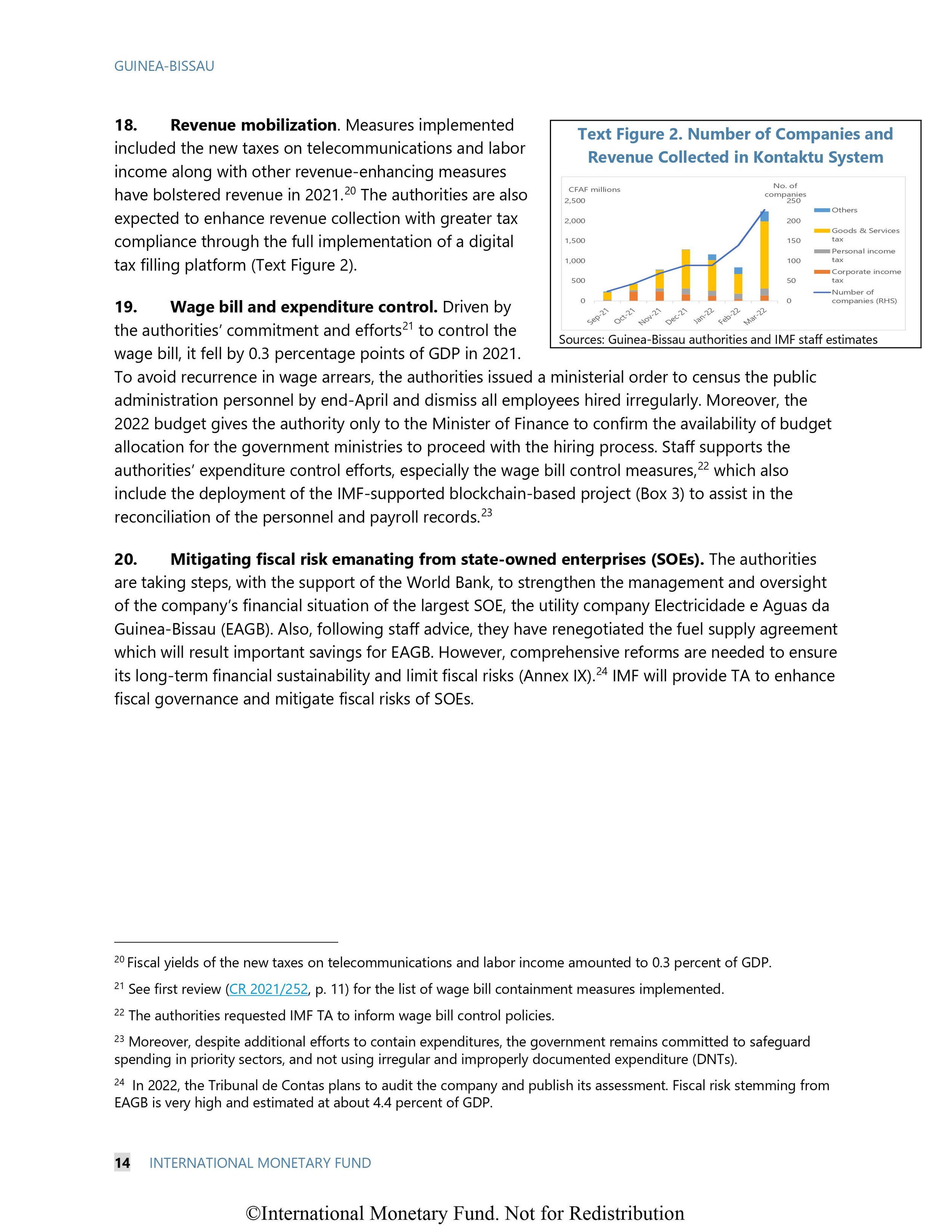

One began to export raw materials exclusively from 'Portuguese' Guinea to Portugal. Unable to make profit, the non-Portuguese commercial enterprises began to leave the country. Peanuts, just as other products of 'Portuguese' Guinea, upon export to Portugal were re-exported to other countries to the profit of Portuguese merchants and to the detriment of the Guinean producer, since the price on the Portuguese market was inferior to that of the world market.

With the eventual development of the peanut-oil industry in Portugal nothing changed in this situation. On the contrary, the increased demands from Portuguese capital (financial, industrial and commercial) imposed new sacrifices on to the Guinean producer now forced to cultivate peanuts and to sell it at prices fixed by the colonial administration.”

So here we see that since the coming of Europeans to Guinea Bissau, the economy was first dominated by kidnapping and selling people into slavery and then shifted to mono-mercantilism of peanuts for the benefit of Europeans. It was an extractive economy - taking the natural wealth of the land of Guine out to Europe through the coerced and forced low paid labour of the people of Guine. This resulted in soil erosion and the political and economic dominance of the Europeans. What was needed then, and is still needed today, is the transformation of the mono-cropping extractive agro-mercantile system of peanuts (back then and of cashews today) into sustainable agro-ecological agro-mercantile system that is non-extractive and benefits the people of Guinea Bissau. This was similar to the same problem that faced the American South in the early part of the twentieth century.

Consider that in my presentation to the New Afrikan Though Conference in Yaounde, Cameroon in November 2022, I made the startling statement,

“In 1864, George Washington Carver was born into slavery in the United States. He had the ability to talk to plants. This ability allowed Mr. Carver to pioneer agricultural science and revolutionize the economy in the American South. When asked about how he was able to create more than 300 different products from the peanut, Dr. Carver said, “I talk to the little peanut and it reveals its secrets to me.” Few people today remember the fame and impact Dr. Carver had on American society. But here we have solid ground that mysticism can be the basis of agricultural science and economic transformation. Imagine a cadre of young people who can solve Africa’s agricultural and forestry and fishery and housing problems by talking to the environment and getting answers directly from it without the use of books and professors . . .“

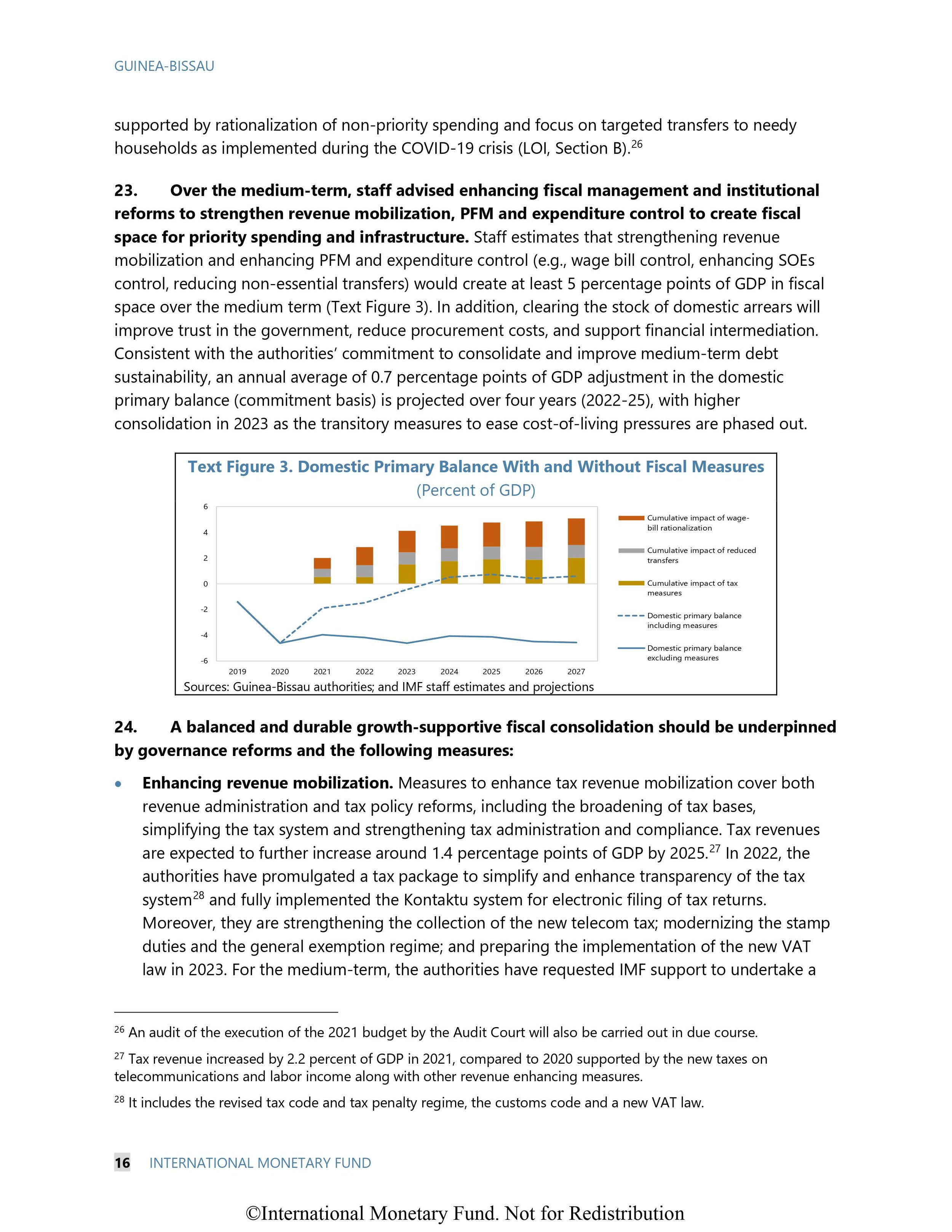

One man taught the former slaves in the American South how to make 300 different products from the peanut! Imagine if one man with Dr. Carver’s abilities was in Guinea Bissau!

In my presentation, I further noted,

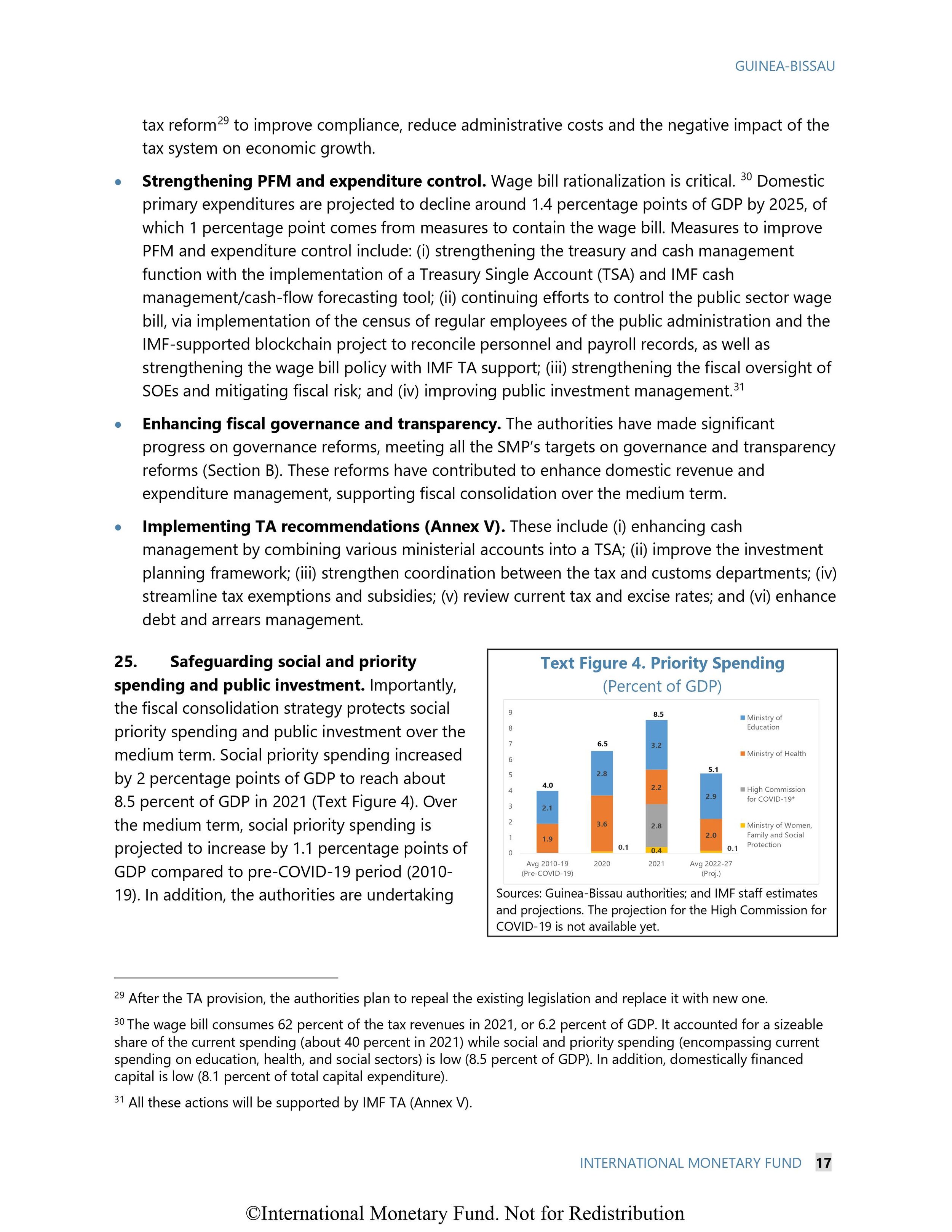

“He pursued an education in agriculture at Iowa Agricultural College, where he encountered a stellar faculty of ‘scientific agriculture’ professors, including two future U.S. secretaries of agriculture, James Wilson and Henry C. Wallace. This was a practical decision: southern blacks could not paint their way out of poverty.

“Carver made quite an impression on the Iowa Agricultural College faculty. His long-nurtured interest in plants had helped him to develop an ability to raise, cross-fertilize, and graft them with uncanny success. His professors were convinced that he had a promising future as a botanist and persuaded him to stay on as a graduate student after he finished his senior year. He was assigned to work as an assistant to Professor Louis H. Pammel, a noted mycologist, later described by Carver as ‘the one who helped and inspired me to do original work more than anyone else.’ Under Pammel’s tutelage, Carver refined his skills of identifying and treating plant diseases. . . .

Carver was in the last year of his stay at Iowa Agricultural College when Booker T. Washington gave his famous Atlanta Exposition speech (1895). That speech was Washington’s clearest expression of a long-held philosophy: that southern blacks needed to accommodate themselves to the reality of white control and win first their economic independence through vocational training and the ancient virtues of hard work and thrift. As a means to that end, Washington accepted a position as the first president of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1881. By 1896, he had persuaded the board of trustees to establish an agricultural school. Carver, the only black man in the country who had graduate training in ‘scientific agriculture,’ was the logical choice for the Tuskegee leader, who wanted to keep his faculty all black.

So it was that late in 1896, Georege Washington Carver traveled to the struggling Tuskegee Institute, where he promised Booker T. Washington he would make grass grow green in the Alabama clay. . . . He would combine the creativity of the artist with the rationality of the scientist to do what had never been done. . . .”

According to Glenn Clark, author of The Man Who Talks With The Flowers,

“I found myself in an auto driving toward the Mecca of my dreams, Tuskegee, where the old black man wove his fairy land of magic. ‘You see,’ said Jim, pointing across the flat plains we were riding through,

‘that all this land was once planted in cotton. Dr. Carver saw quickly after he came down to Tuskegee that single crop cotton was wearing out the rich Alabama soils, and impoverishing the debt-burdened sharecropper. He wrote farming bulletins and made speeches urging farmers to grow crops in rotation. He discovered that the sweet potato and the peanut were crops which this soil brought forth in greatest abundance. He preached the gospel of rotating cotton crops with peanut and sweet potato crops. But when the farmers followed his advice in large numbers they discovered they were producing more peanuts and sweet potatoes than the market could absorb. So in solving one problem he had created another. Here was a real problem to face. He didn’t tackle it by asking the government to give federal aid nor did he demand that it restrict planting. He tackled it in the chemical laboratory and licked it there. He discovered 300 new uses for the peanut and 150 new uses for the sweet potato and before he was through he had rebuilt the agriculture of the South. Edison offered him an immense salary for him to come and help him, but he declined. A few years later he declined another offer from a firm for $100,000 so as to give himself wholeheartedly to the saving of the farmers of the South. Today he accepts no salary, and wears an old black suit he bought for about $2.00; but you will find that he always wears a flower in his buttonhole.

Perhaps the most dramatic episode of Dr. Carver’s life was when he went to Washington. When the Ways and Means Committee of the United States Senate were holding hearings on the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Bill, the southerners were very anxious that they should be included. Among those asked to speak was Dr. Carver. When he got off the train, he stopped one of the porters and asked him directions to the Senate.

‘Sorry, Pop,’ he replied, ‘I ain't got time to tell you now. We’re looking for a great scientist up here from Alabama.’

Dr. Carver was put off till the last of the dozen men to speak. Each had been allotted ten minutes. When he came up in his old coat and home-made necktie the committee broke out laughing. One called out, ‘What do you know about the tariff, old fellow?’ ‘I don’t know much, but I know it’s the thing that shuts the other fellow out.’ They caught the point.

But they certainly didn’t put a ‘tariff’ on Dr. Carver’s talking. For after he had talked the ten minutes allotted to the others they all insisted, yes, begged and pleaded that he go on. For an hour and forty-five minutes he showed them face powder, axle grease, printer’s ink, milk, cream, butter, shampoos, creosote, vinegar, coffee, soaps, salads, wood stains, oil dyes, and so on and on. Needless to say the peanut was included in the tariff.

This wasn’t the only time he was called to Washington. During the World War when soldiers needed most of our wheat supply and we had our meatless, wheatless and sweet-less days, the government tried to find a substitute for wheat. Meanwhile at Tuskegee Institute they were saving 200 pounds of wheat flour a day by using sweet potato flour with wheat flour and even, by Dr. Carver’s own admission, ‘making a better load than before.’ Again the U.S. government sent for Dr. Carver to come to Washington, this time not with peanuts, but with a sweet potato exhibit. He simply amazed the experts who had gathered to confer with him. It was after the conference that Dr. David Fairchild, agricultural explorer in charge of the United States Department of Agriculture and world famous scientist, spoke of Dr. Carver as ‘one of the most remarkable and extraordinary minds I ever met.’”

Upon reaching Tuskegee and Dr. Carver, Clark writes,

“Here is what I call God’s Little Workshop,” said Dr. Carver, and the next moment we had entered the sacred precinct of his place of miracles. ‘No books are ever brought in here,’ he went on, ‘and what is the need of books? Here I talk to the little peanut and it reveals its secrets to me. . . . Here I talk to the peanut and the sweet potato and the clays of the hills, and they talk back to me. Here great wonders are brought forth.’ And he pointed to an array of bottles containing specimens of the three hundred uses for the peanut - no, three hundred and one, for this morning he had discovered a new one. . . . And up there along the walls are the clays,’ he added. ‘Again there is no need for books.’”

Dr. Carver testified to having the power of remote visioning as well as the power to communicate with the supreme intelligence in the external environment through extra sensory perception. As a result of these powers, he becme the Negro Master of Agricultural Science, rebulit the agriculture and economy of the American South, became a saviour to the United States government, and was recognized by all for having a “most remarkable and extraordinary mind.”

Dr. Carver accomplished all this in the most racist country on earth during an era of Jim Crowism and lynchings. We can imagine, then, the impact that just one man or woman with the same powers of remote viewing and extra sensory perception, the ability to communicate with ancestors and the supreme intelligence both within and without the body, could have on transforming Guinea Bissau’s agriculture, economy and all other aspects as well.

Where will such a gifted person come from? How will Guinea Bissau produce its own “Dr. George Washington Carver”?

GUINE BISSAU’S CASHEW MONO-MERCANTILE SYSTEM

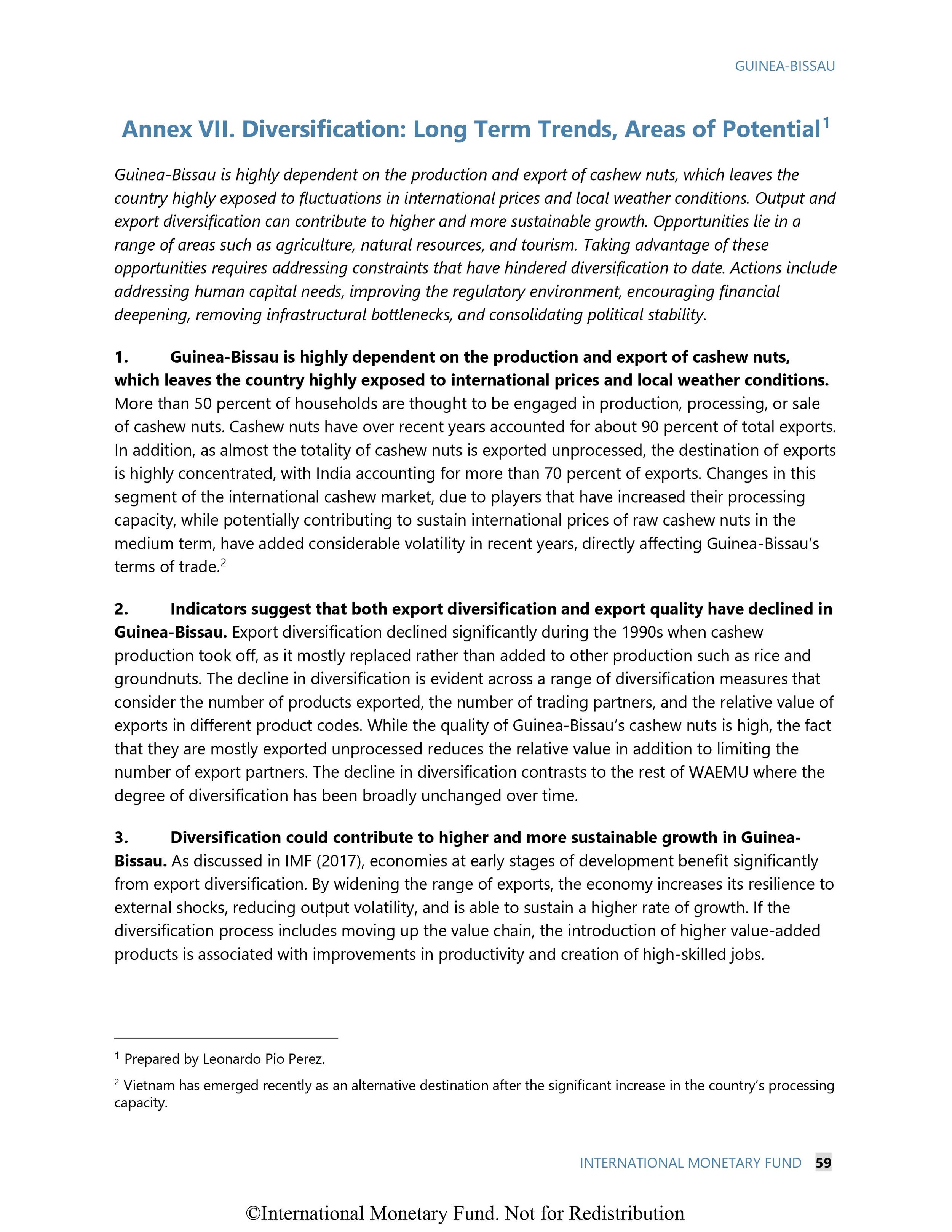

The leaders of Guinea Bissau today have not listened to Amilcar Cabral and have failed to learn the lesson. One need only look at today’s cashew mono-mercantile system in Guinea Bissau.

The cashew tree, A. occidentale, of the Anacardiaceae family, is an evergreen tree growing to a height of 8-20 m depending on soil characteristics and climate. It normally starts flowering by the third year, attaining full production by the eighth year. The period of full production can last up to 20-30 years and the lifespan of the tree is variable. The nut, which is the true fruit, is a kidney-shaped achene that does not split open after drying. Inside the shell, which contains corrosive oil, is a large curved 2-3 cm seed, the edible cashew nut. As the nut matures, the peduncle at the base enlarges into a fleshy, bell-shaped, fruitlike structure, popularly known as the false fruit or cashew apple. This thin-skinned edible false fruit has yellow spongy and juicy flesh, which is pleasantly acidic and slightly astringent when eaten raw, but highly astringent when green (Behrens, 1996).

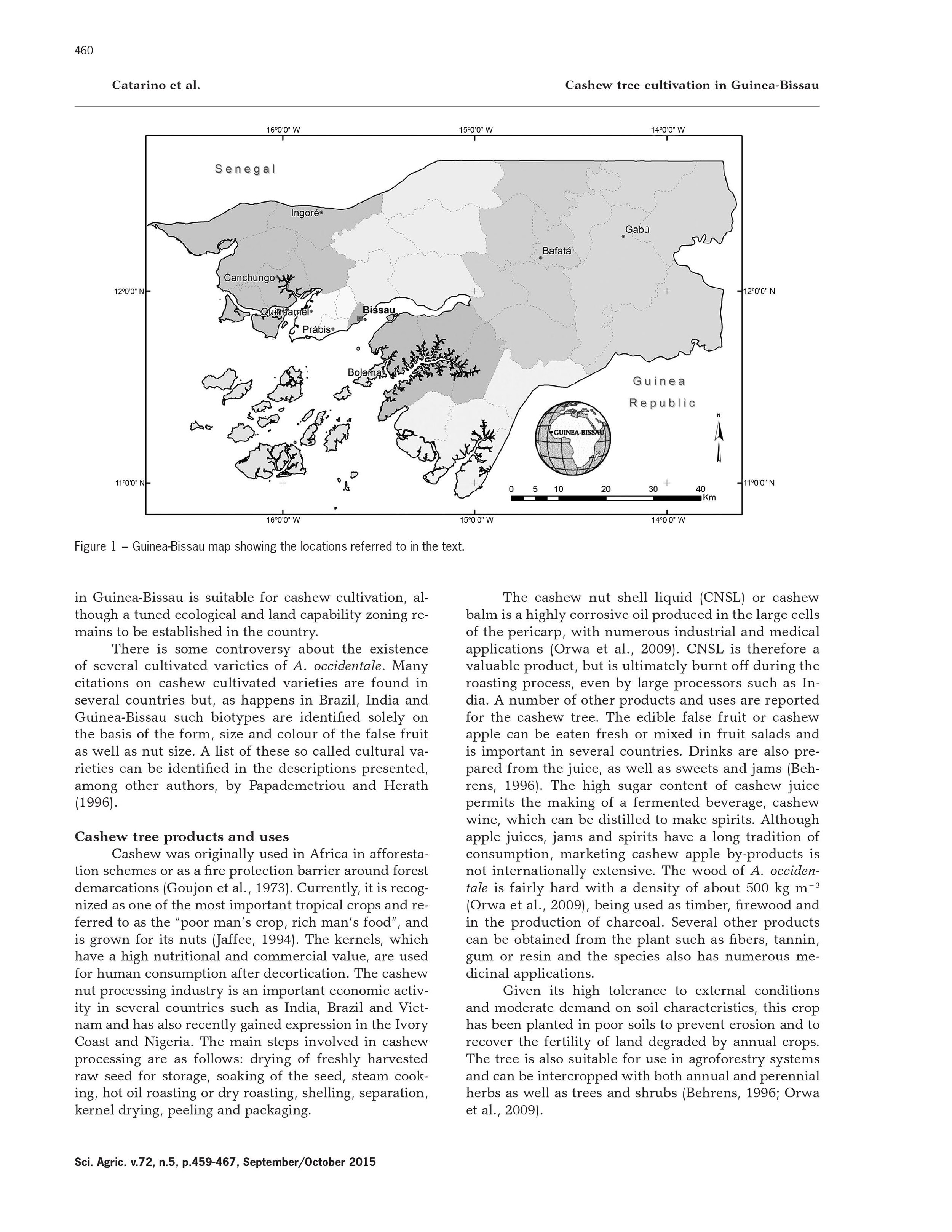

The cashew tree grows at altitudes of up to 1000m, in mean annual temperatures ranging from 17-38 ºC, and does not tolerate frost. Distribution of rainfall is more important than the amount, and the tree grows in a range of 500-3500 mm of rainfall. This crop is able to adapt to very dry conditions, as long as its extensive root system has access to soil moisture. It prefers deep and fertile sandy soils but will grow well on most soils except pure clays or soils that are otherwise impermeable, poorly drained or subject to periodic flooding. It fruits well if rains are not abundant during flowering and if the nuts mature during the dry period. With this generic classification, and disregarding the edaphic constraints, all territory in Guinea-Bissau is suitable for cashew cultivation, although a tuned ecological and land capability zoning remains to be established in the country.

Following the rainy season which begins in late May and ends in early November, the cashew trees absorb the soil’s nutrients. In January and February, the trees bloom after which the blossoms turn into the cashew fruit that is harvested between April and June.

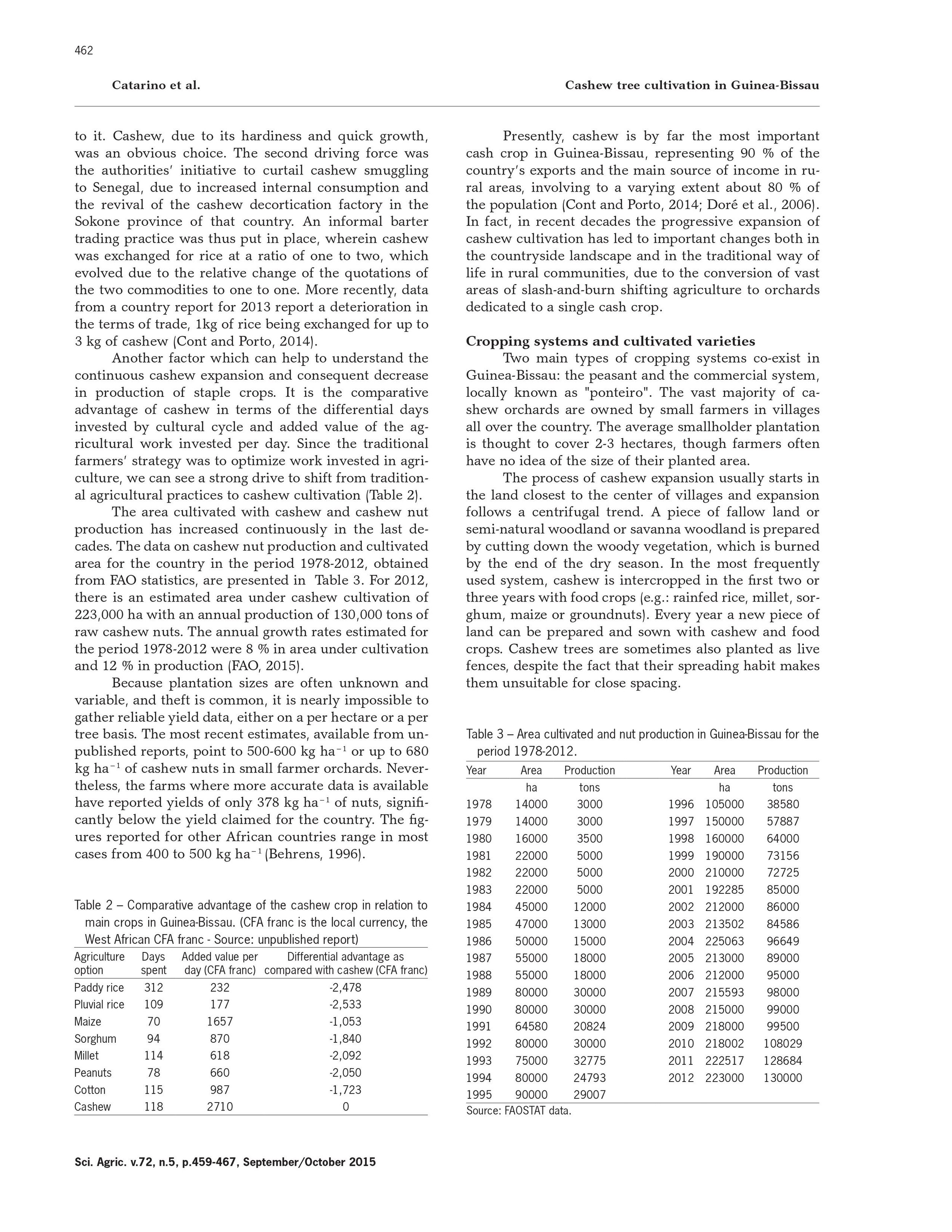

The cashew tree was introduced into Guinea-Bissau by the Portuguese in the XIXth century and during the early XXth century and was mainly used in local farmers’ home gardens. Cashew cultivation had a first organized impulse under the instigation of Governor Sarmento Rodrigues (1945-1949), who promoted its expansion. By the mid-1950s, nut production was estimated to reach 300-400 tons per year. The potential value of the cashew tree, its hardiness and the possibility for use in intercropping or as a kind of cover for long fallow periods in order to recover soil fertility, has been suggested as a priority for research and experimentation. As a consequence, the Overseas Agronomic Research Mission (MEAU) designed the Cashew Development Plan in Portuguese Guinea. The plan was developed under an integrated value chain perspective, considered necessary for the development of the territory and its people. Thus, to fulfill its objectives, during the 1960s MEAU set up a multi-disciplinary six year research project. Given the tree’s rusticity, MEAU promoted cashew cultivation in soils depleted by other crops such as maize, upland rice or groundnuts, as well as by fire (Sardinha). As a result of such research that emphasized the financial comparative advantage of cashew crops, production skyrocketed.

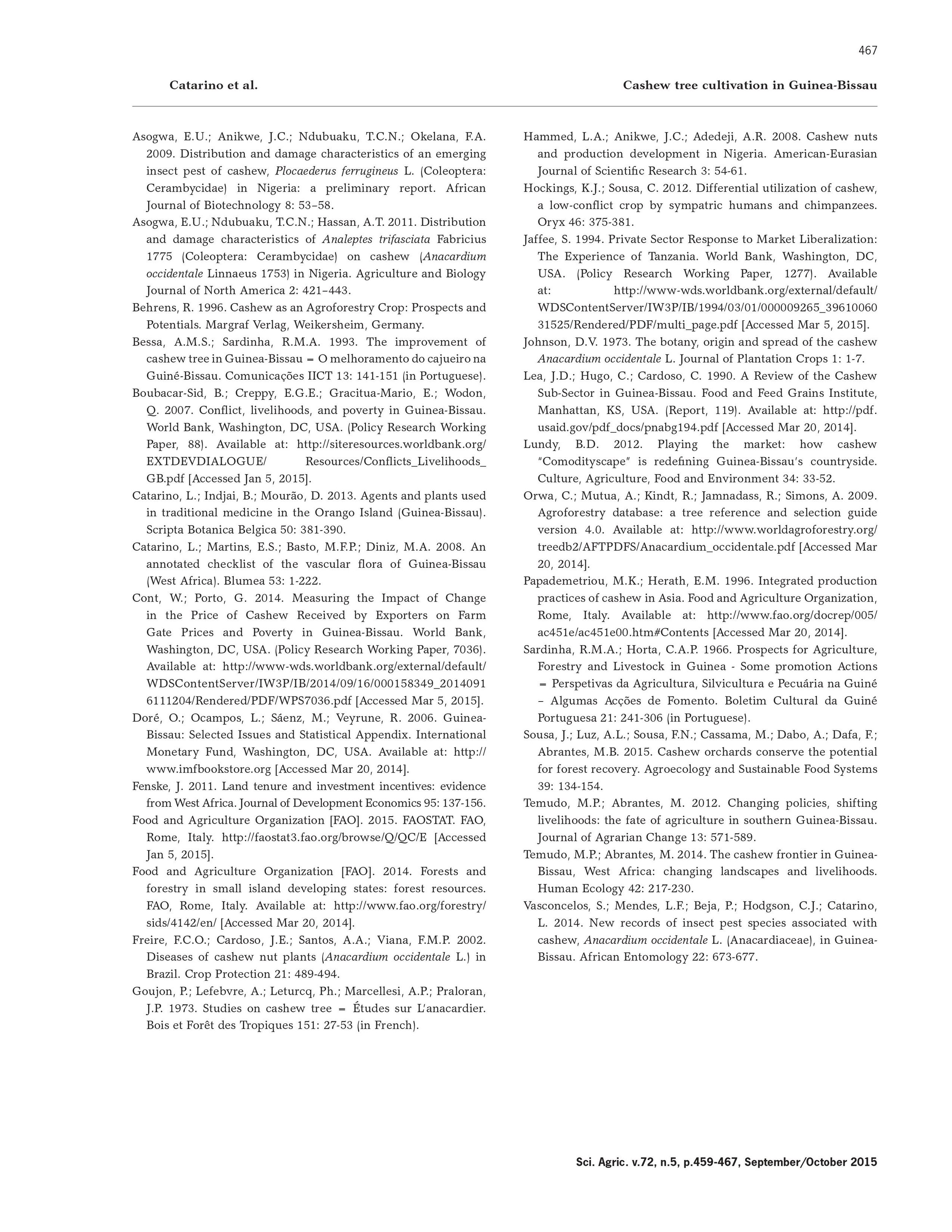

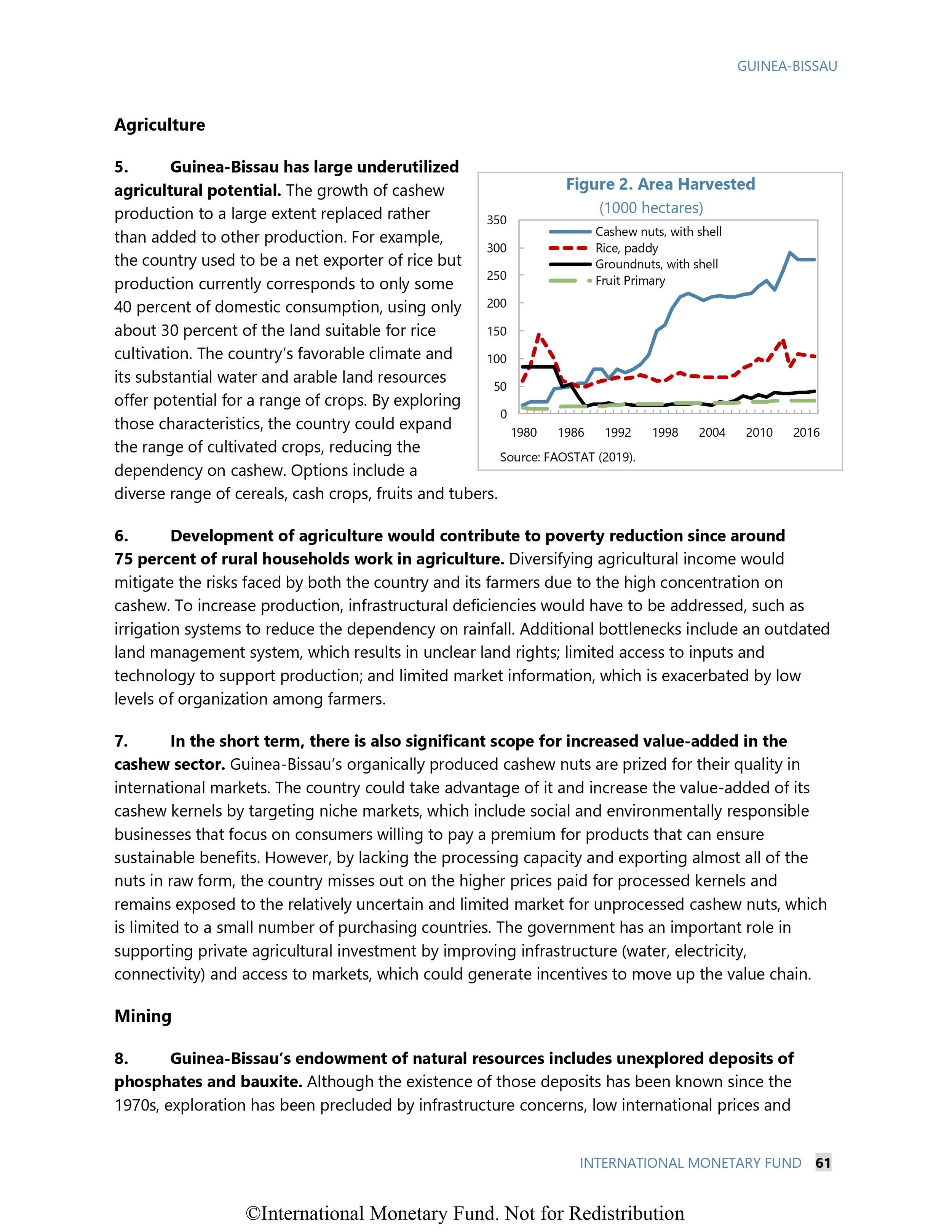

Guinea Bissau is now the second-largest cashew producer in West Africa and in the top five globally. An estimated 223,000 hectares are under cashew cultivation. Today, about 85% of the population depends on cashew farming.

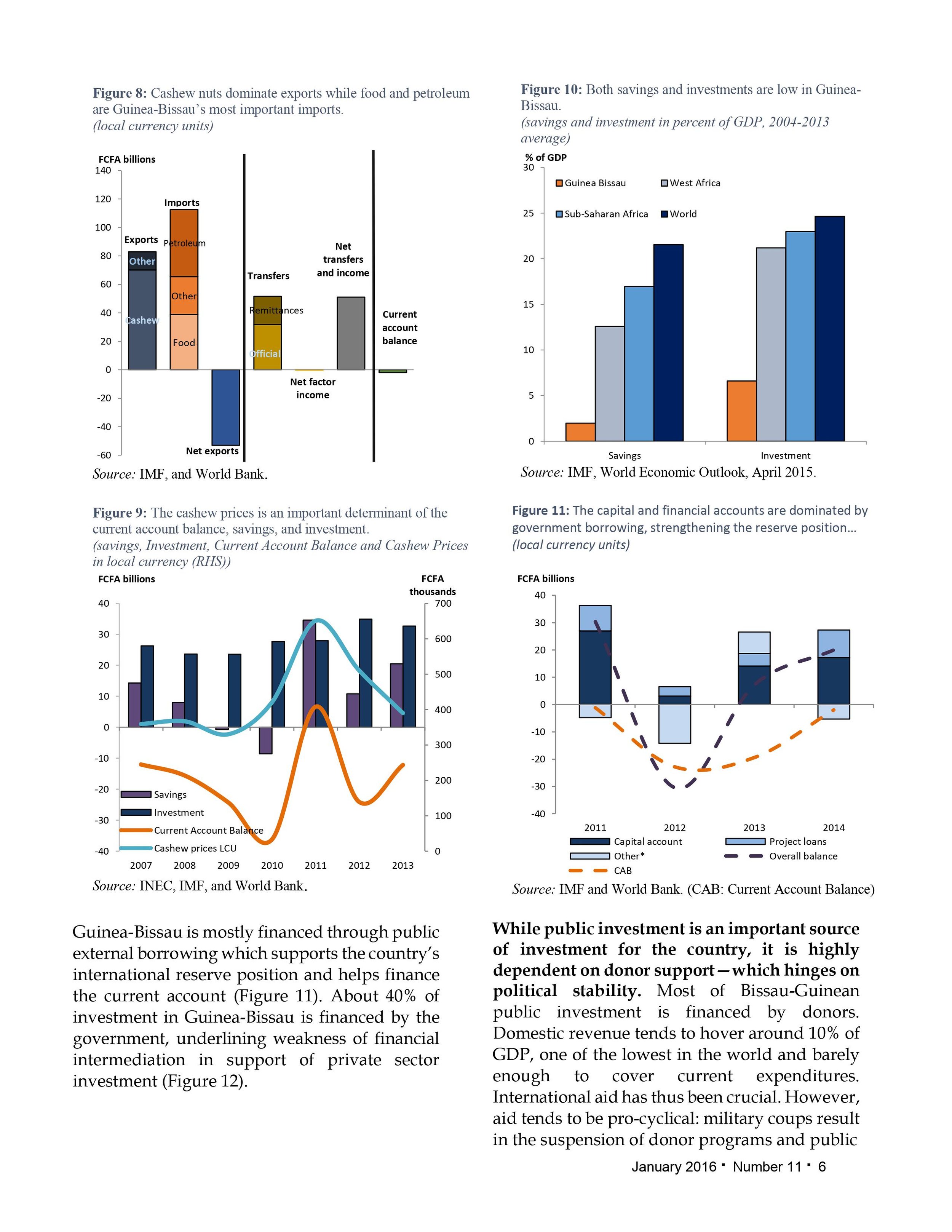

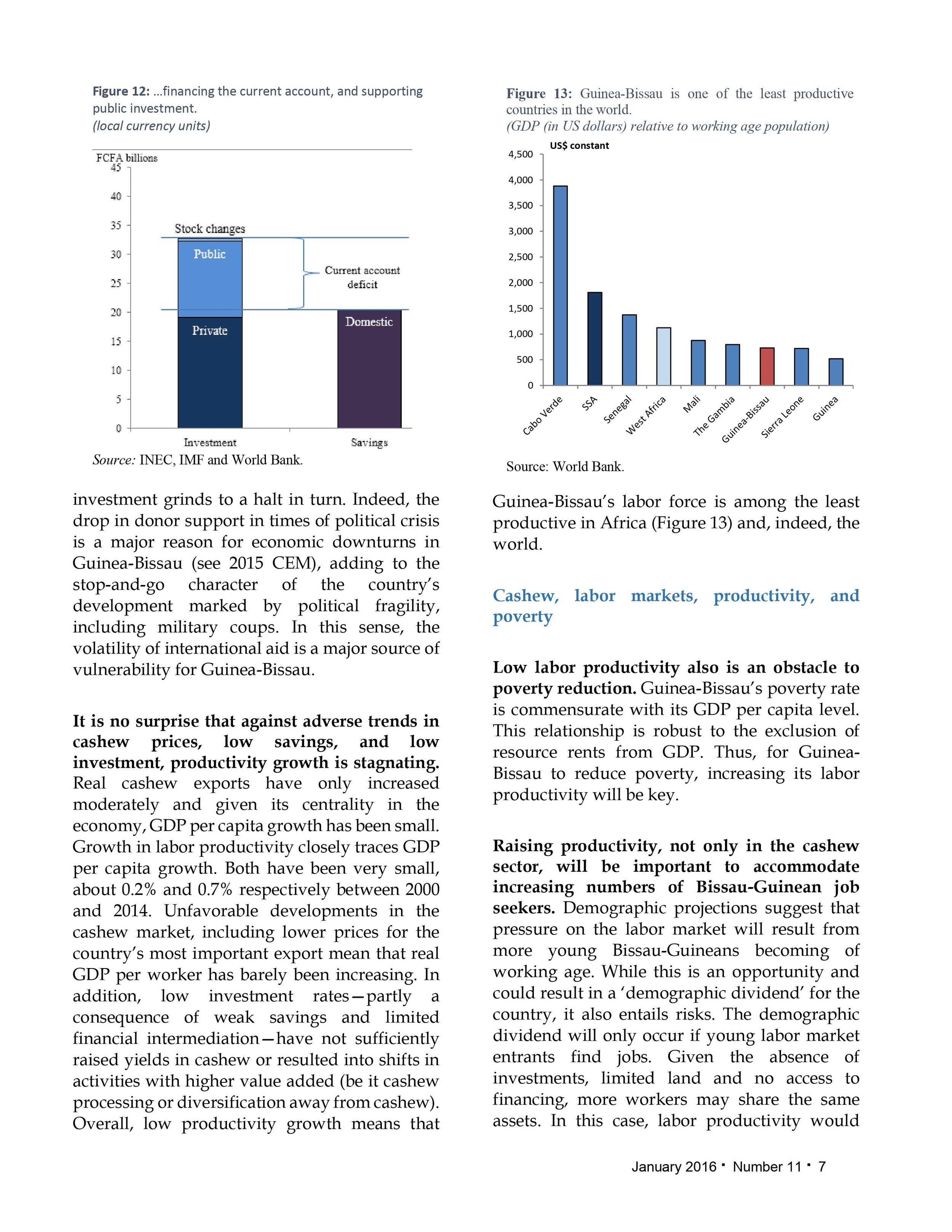

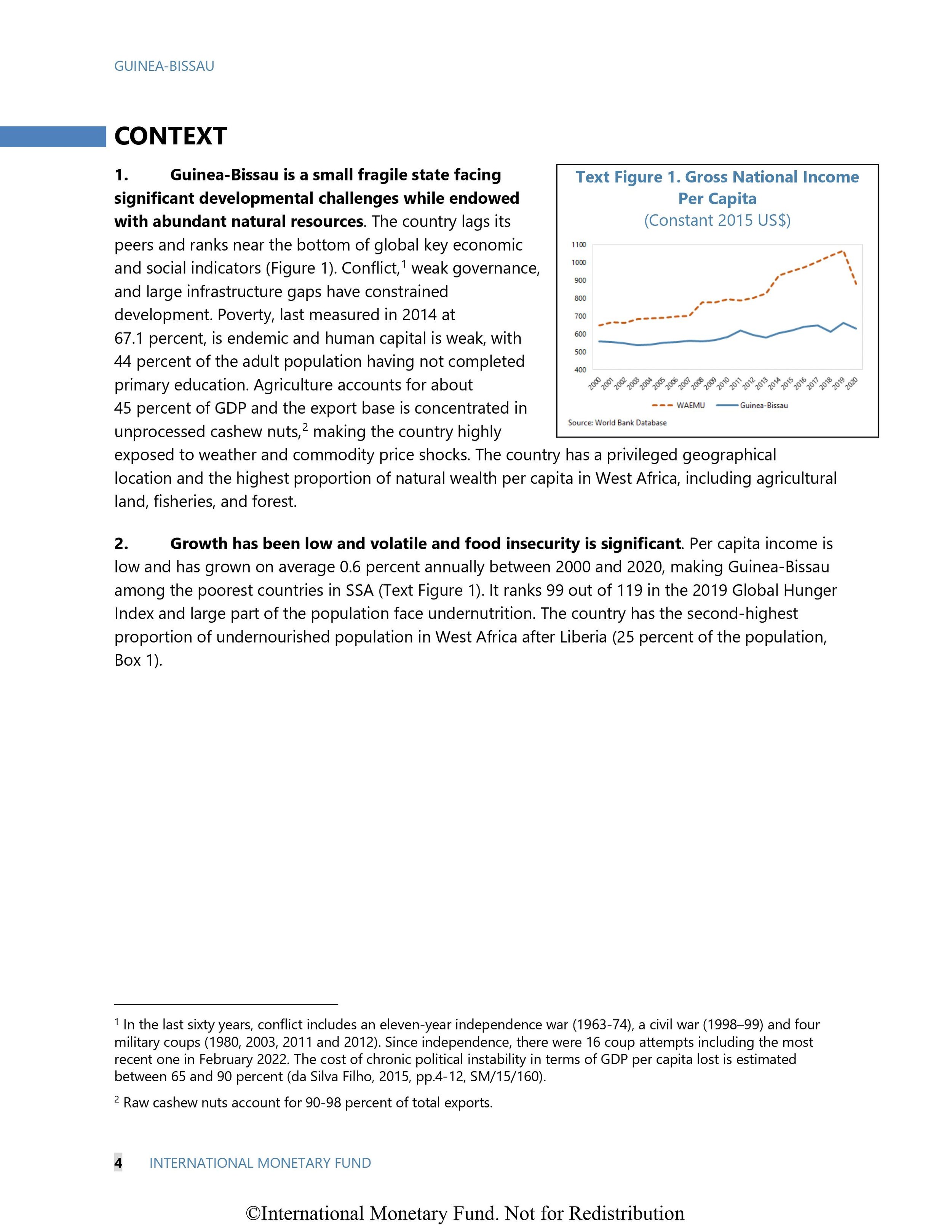

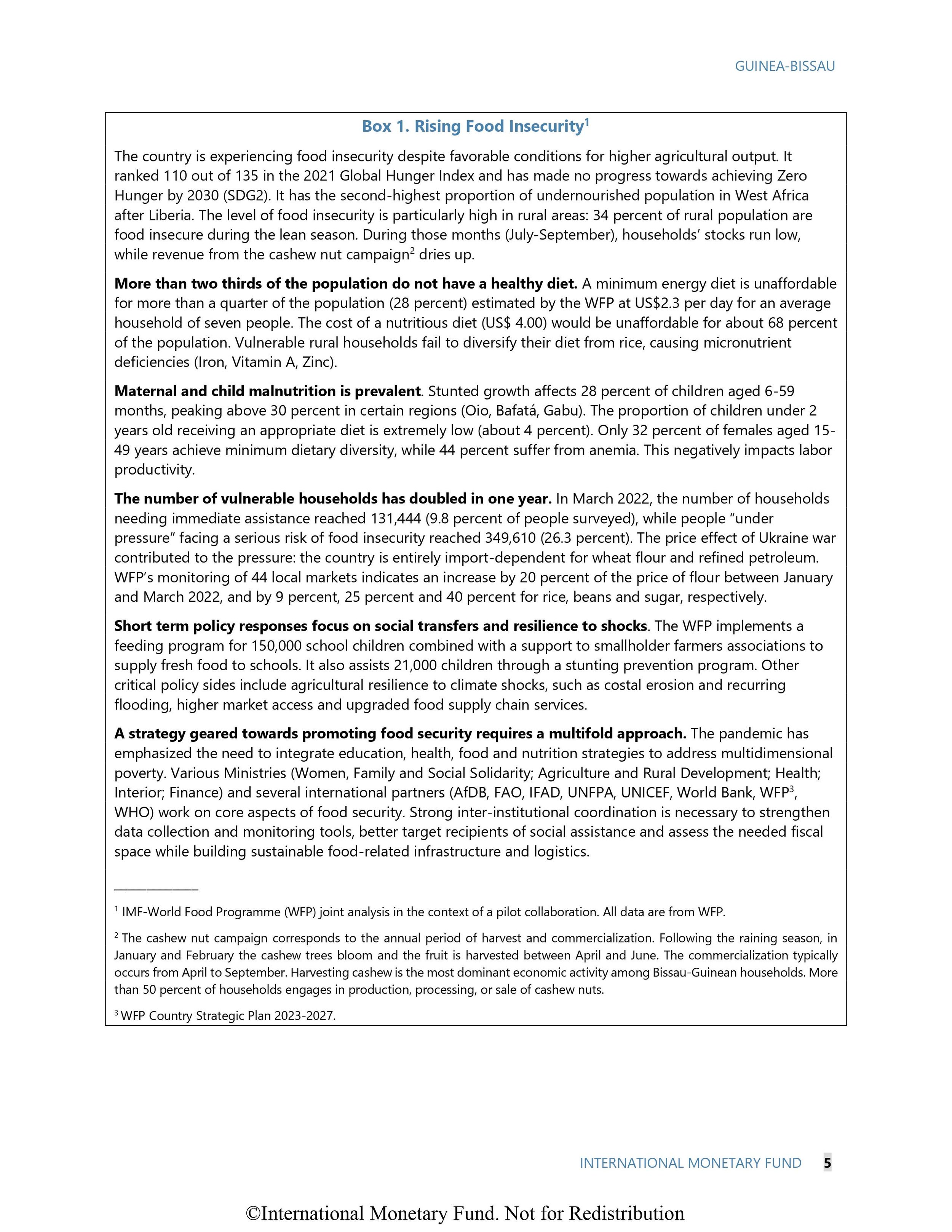

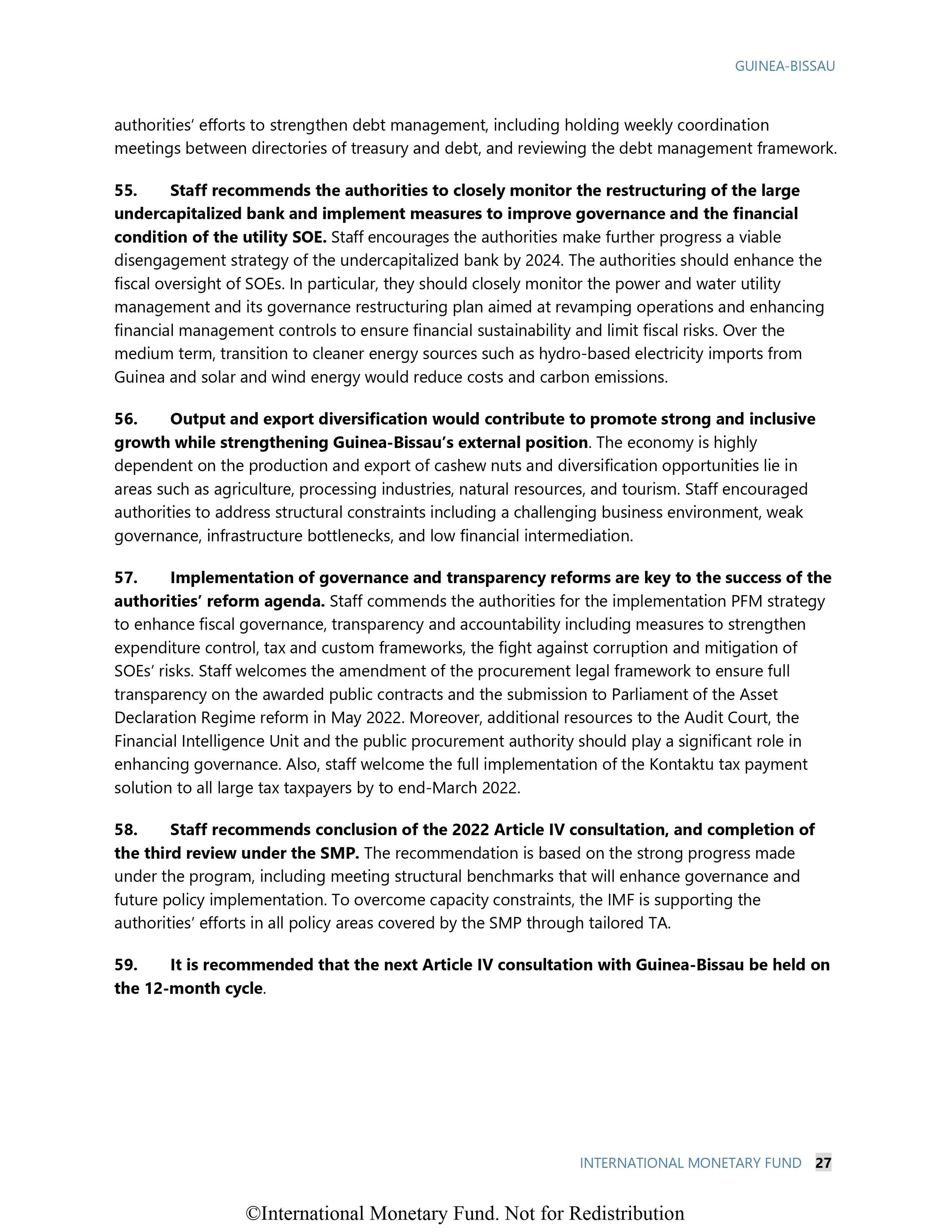

“From a macroeconomic perspective, Guinea Bissau faces two major challenges: low productivity and high vulnerability. Apart from a history of fragility which has been underlying Guinea-Bissau’s stop-and-go character of development, structural economic challenges keep the country from growing at a faster pace that would enable progress toward reducing the high levels of poverty. The dominant cashew sector at least partly lies at the heart of the structural challenges. Whilst export volumes have increased, deteriorating Terms of Trade—especially with respect to rice for which cashew is bartered—have been undermining incomes, domestic savings, and in turn investment. This at least partly explains low productivity levels and the structural slack in the economy. It leaves the country dependent on international aid which is volatile and aggravates the effect of military coups through plummeting public investment—especially given the low levels of domestic revenue. Both Terms of Trade shocks and political shocks are thus amongst the most important sources of vulnerability for Guinea-Bissau’s economy.

Investments to make the cashew sector more productive, but especially to diversify the economy, will be crucial for Guinea-Bissau. The country requires both more jobs and more productive jobs. This is especially true given expected pressures on the labor market from demographic change. Whilst there is room to improve the productivity of the cashew sector, for example by moving into processing rather than raw exports (see 2015 CEM), many of these new jobs will have to be located in other activities. The 2015 CEM and the latest national development plan identify rice, fisheries, tourism, and even mining as potential areas to add productive jobs. The production of groundnuts or sesame are other alternatives. Switching into these areas can not only raise productivity but also diversify the economy, reducing its vulnerability to the cashew price. Attracting FDI by improving the business climate can reduce the country’s dependence on donors for investment and generate knowledge spillovers that can help with the country’s economic transformation.”

A 2015 report stated,

“According to the Minister of Economy and Finance, ‘The cashew campaign is the main source of income of our farmers and the main export commodity of Guinea-Bissau, and about 90 percent of our exports are cashew nuts, a tremendous weighting in our GDP.’

‘In 2015 about 175,000 tons of cashew were exported and this year, we expect to export 180 000 tons, probably a little more given the good prospects for this year's campaign,’ Geraldo Martins explained.

Due to the importance of cashew to the national economy the government in its development strategy focuses on the work of its entire chain, since its production, marketing to export.

‘If all the annual production was transformed locally before export of the finished product, certainly the gain would be much more important, because it would bring added value to the product, given that the price charged for a kilo of raw nuts would not be the same’" he added.

The main obstacles to the transformation of cashew are the acquisition of raw materials for processing, and the actual price of the raw material, said Josué Gomes de Almeida, Coordinator of the Rehabilitation of Private Sector and Support to Agro-industrial Development Project, funded by the World Bank.

‘When the market is good in terms of the price paid to producers, all transformers cry, and when the price is bad for producers, everyone talks about local transformation,’ said Jose Gomes de Almeida, stressing the need for this contradiction to be resolved since ‘in government policy, the fight against poverty must be reflected in rural world where cashew is produced.’

Rui Fonseca, Assistant FAO Programs, recalled that the diversification of agricultural production in the country ‘is important’ and that why his agency will launch ‘a program in partnership with the European Union at the end of April, for cashew improved production quality and also for the development of horticulture.’”

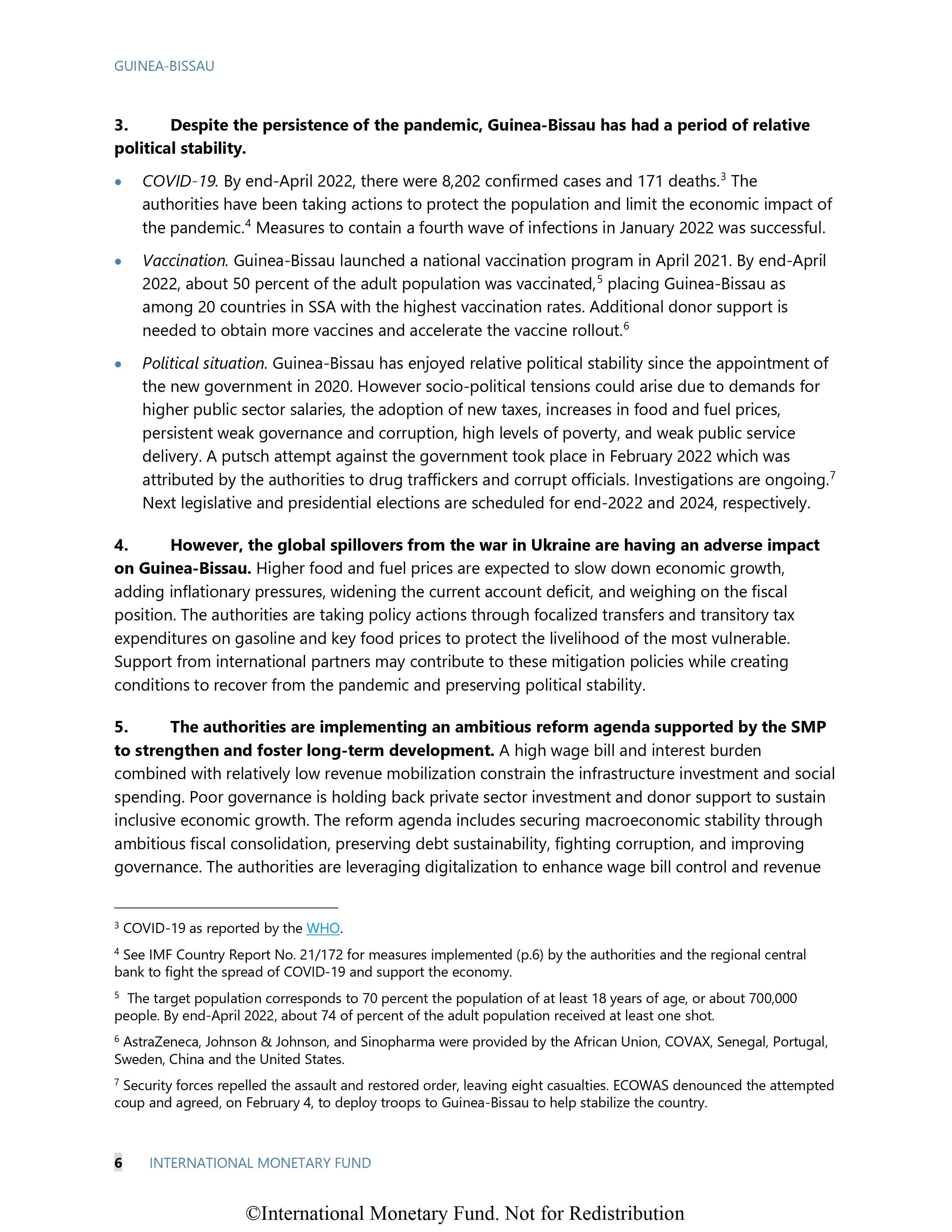

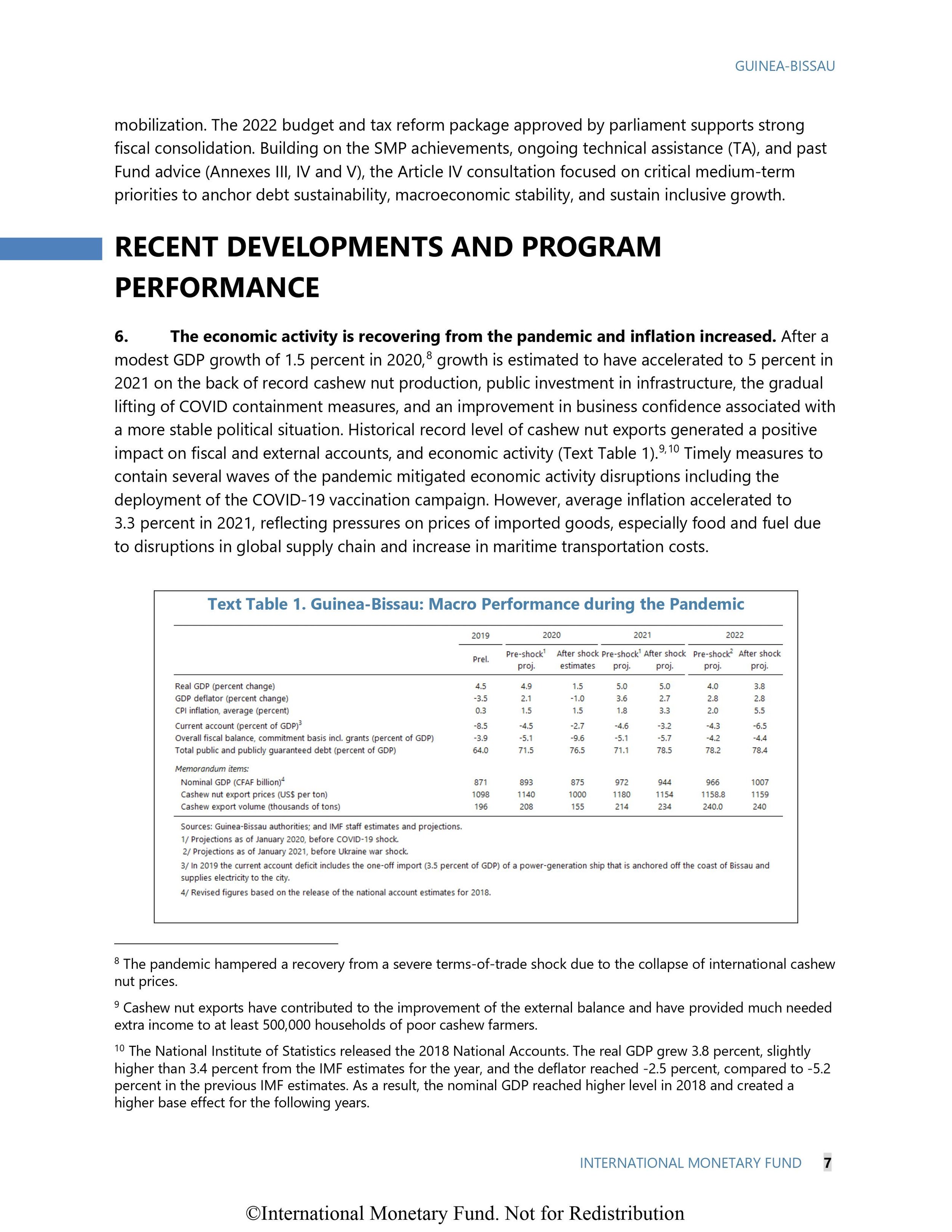

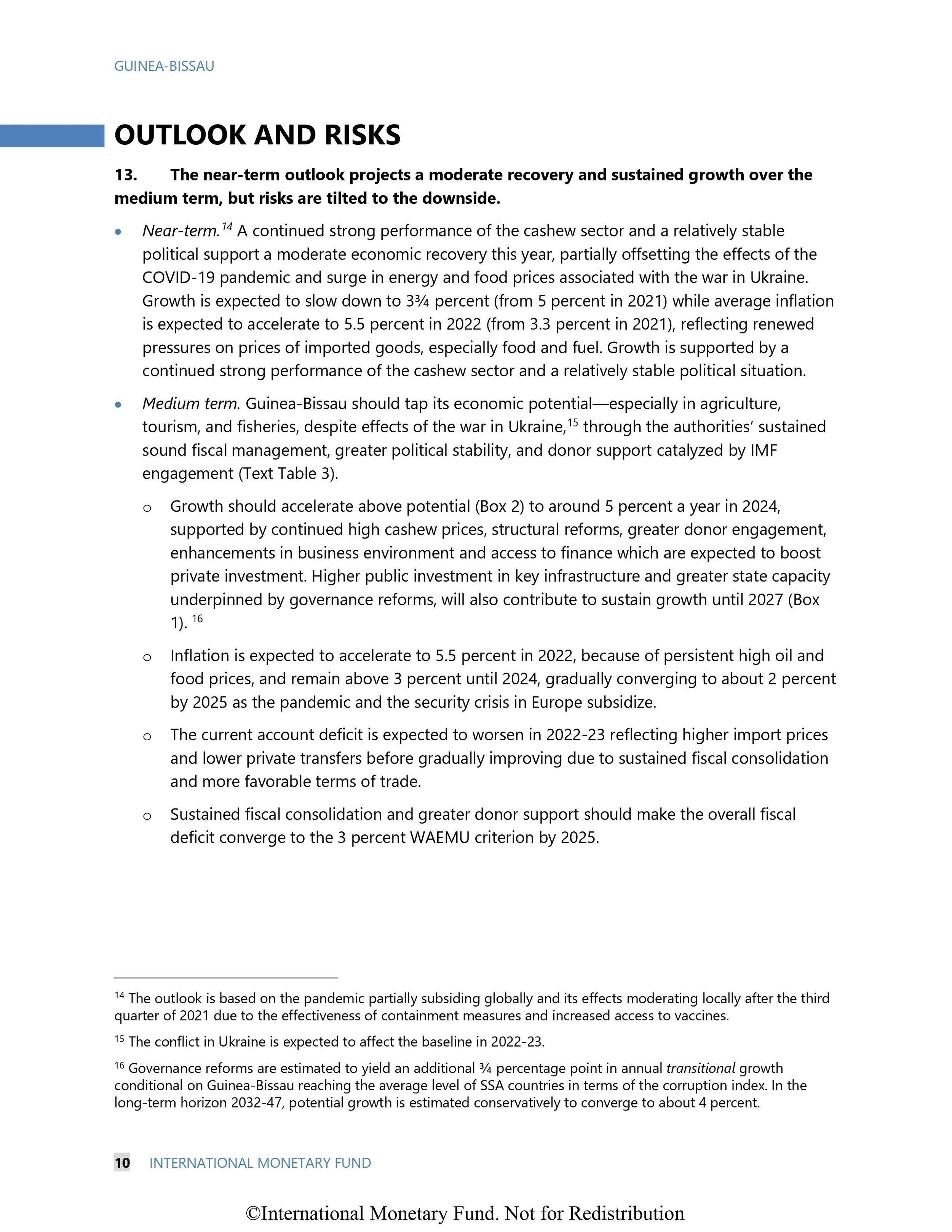

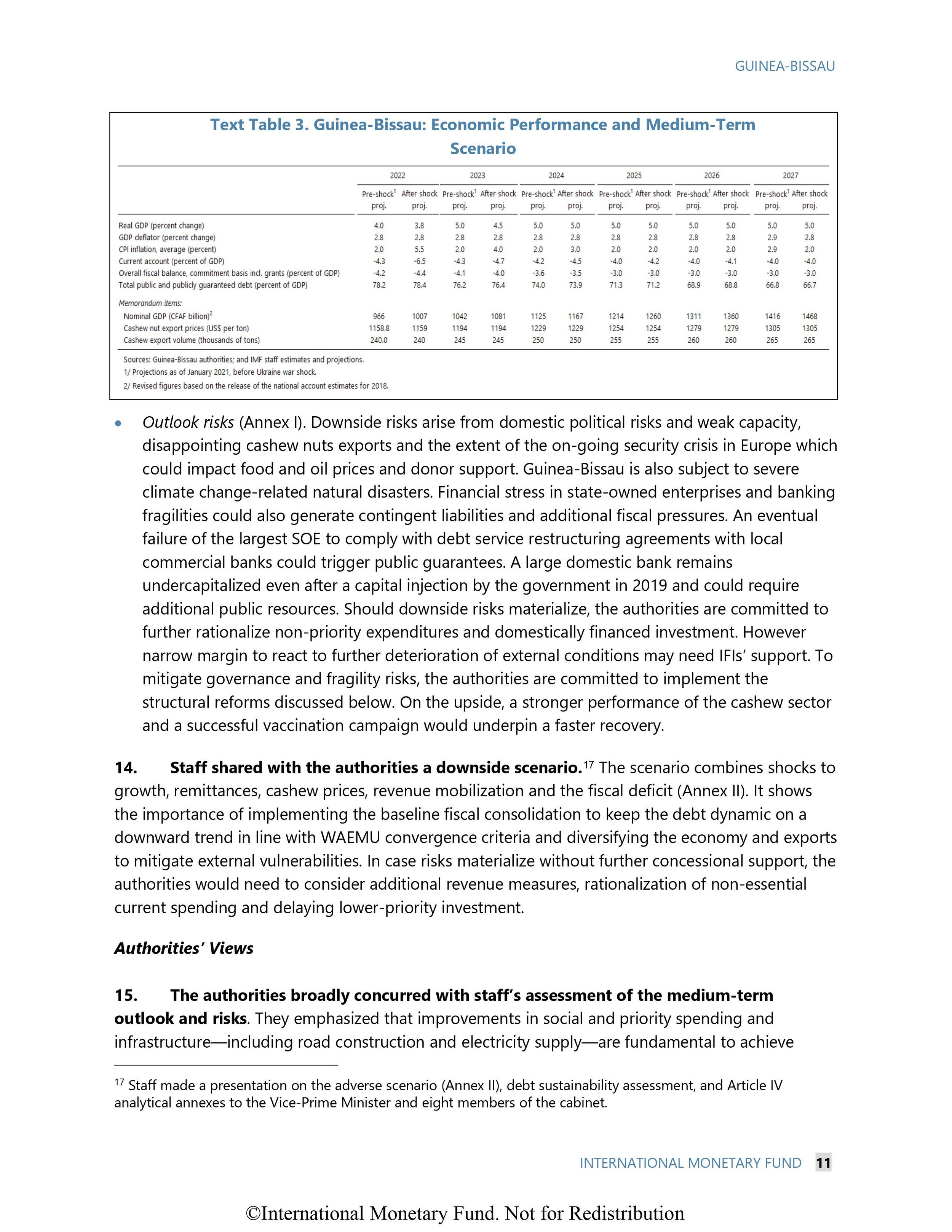

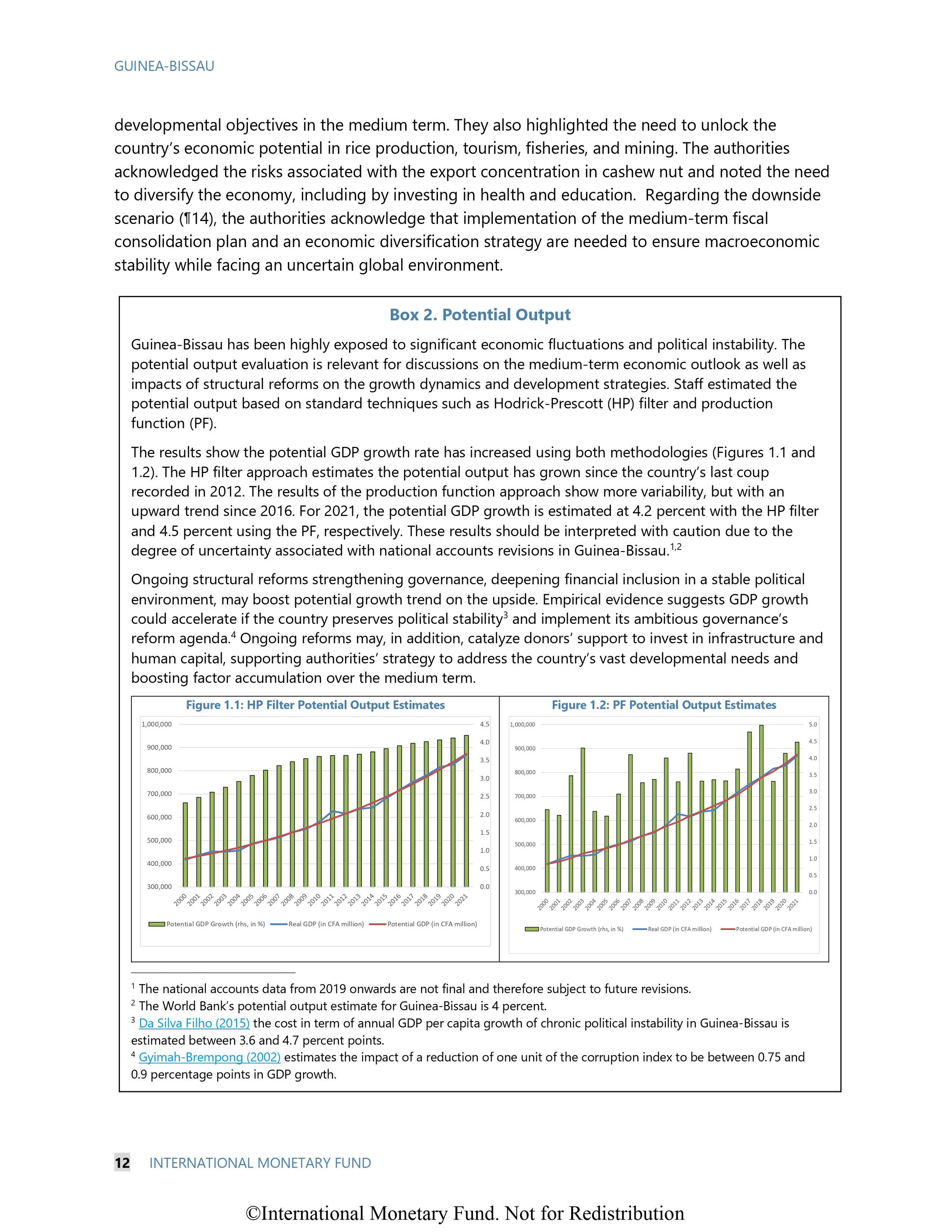

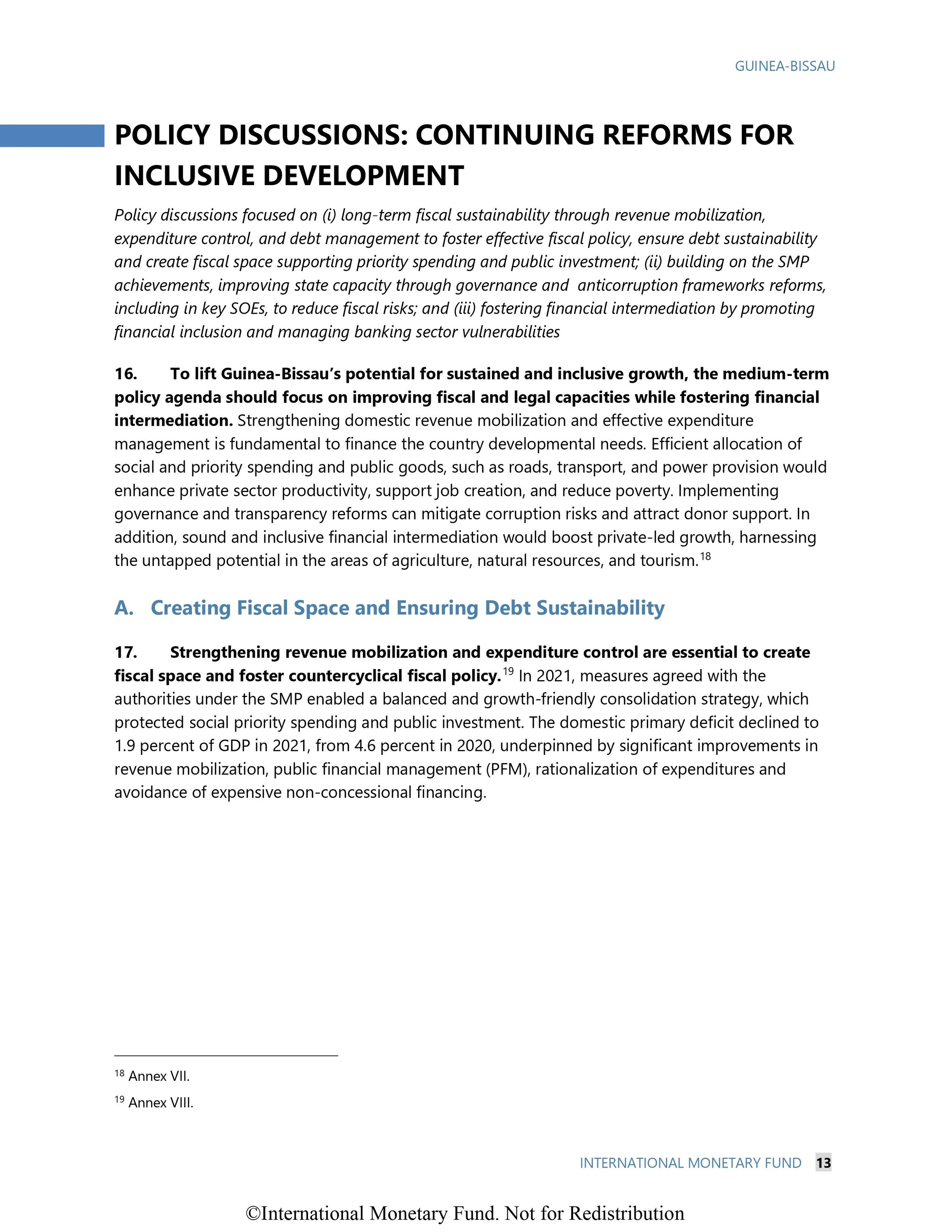

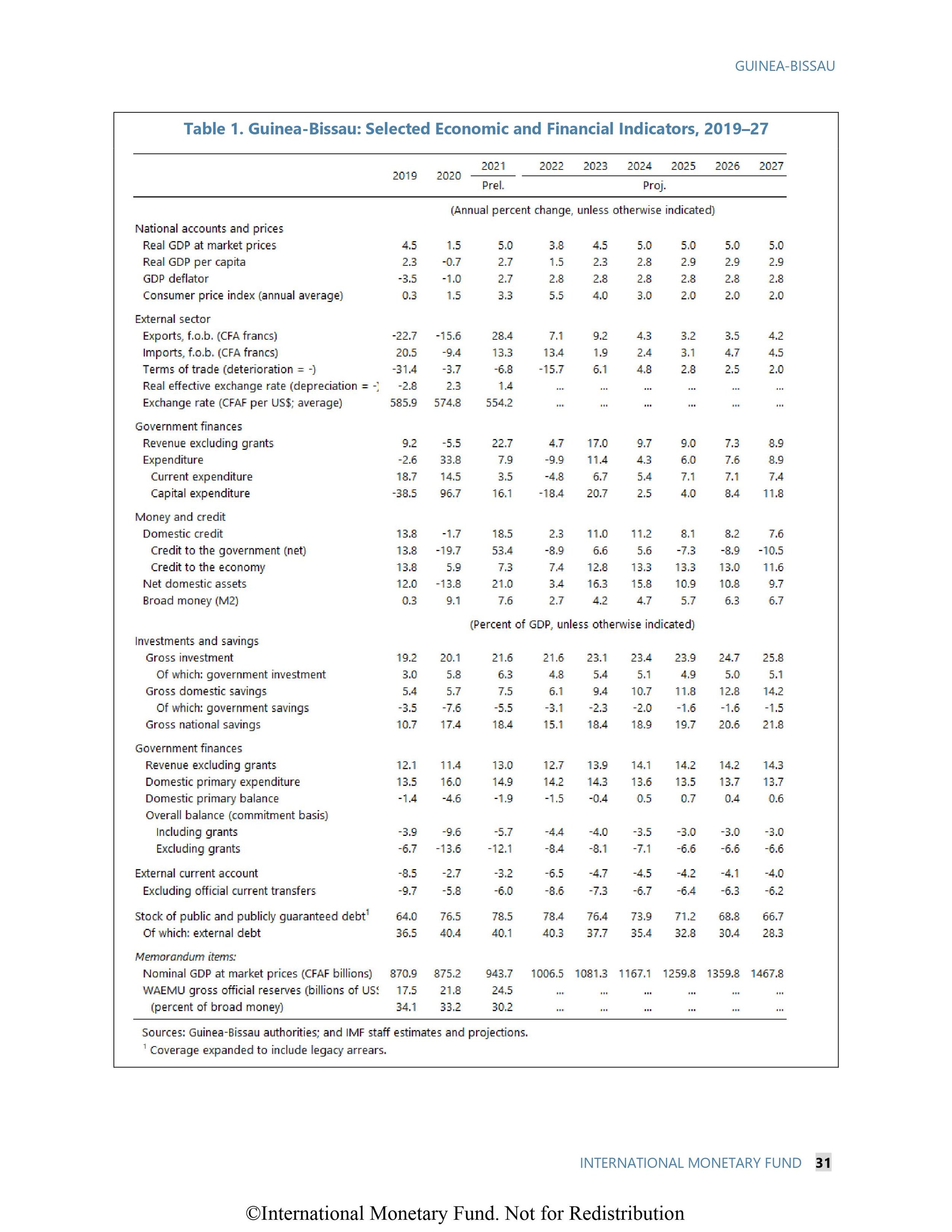

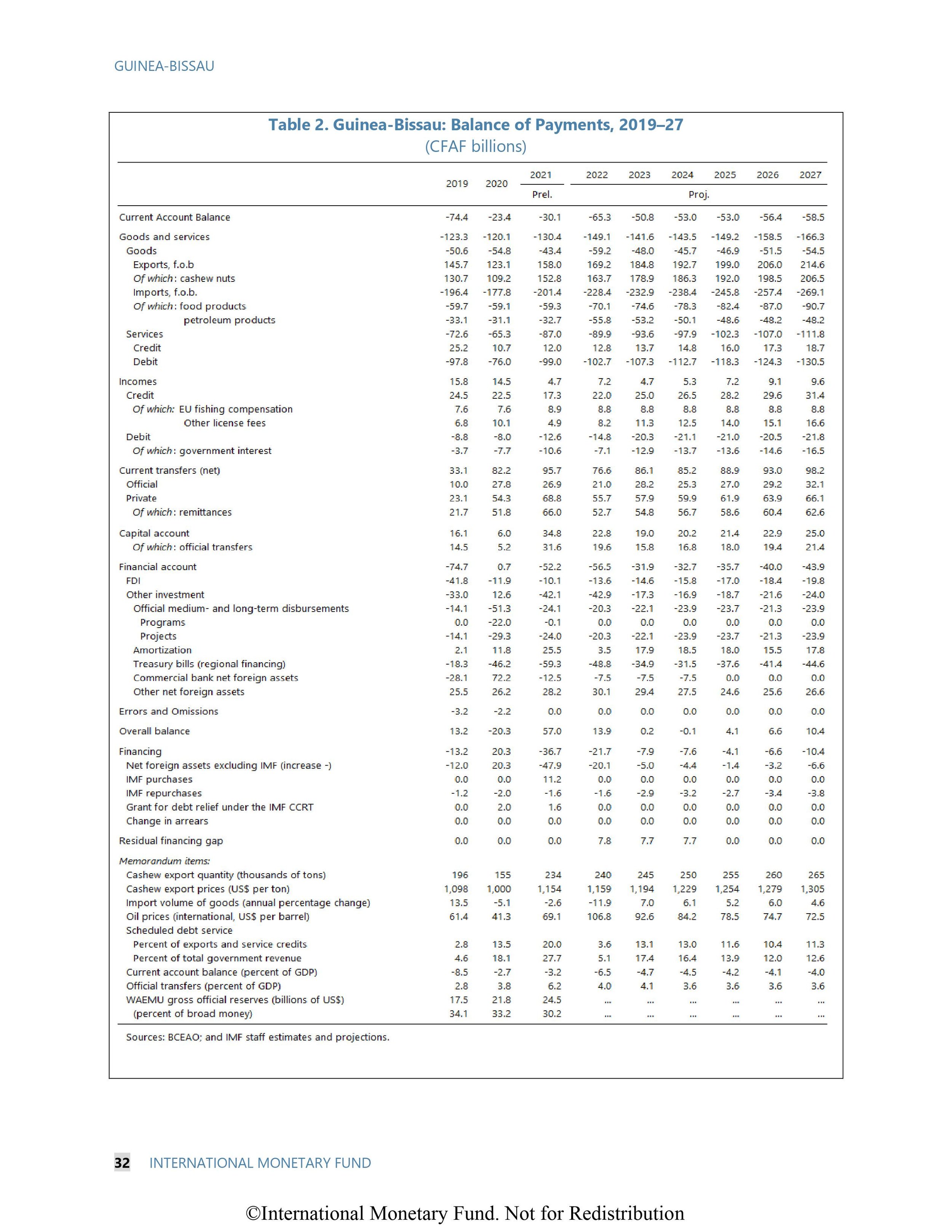

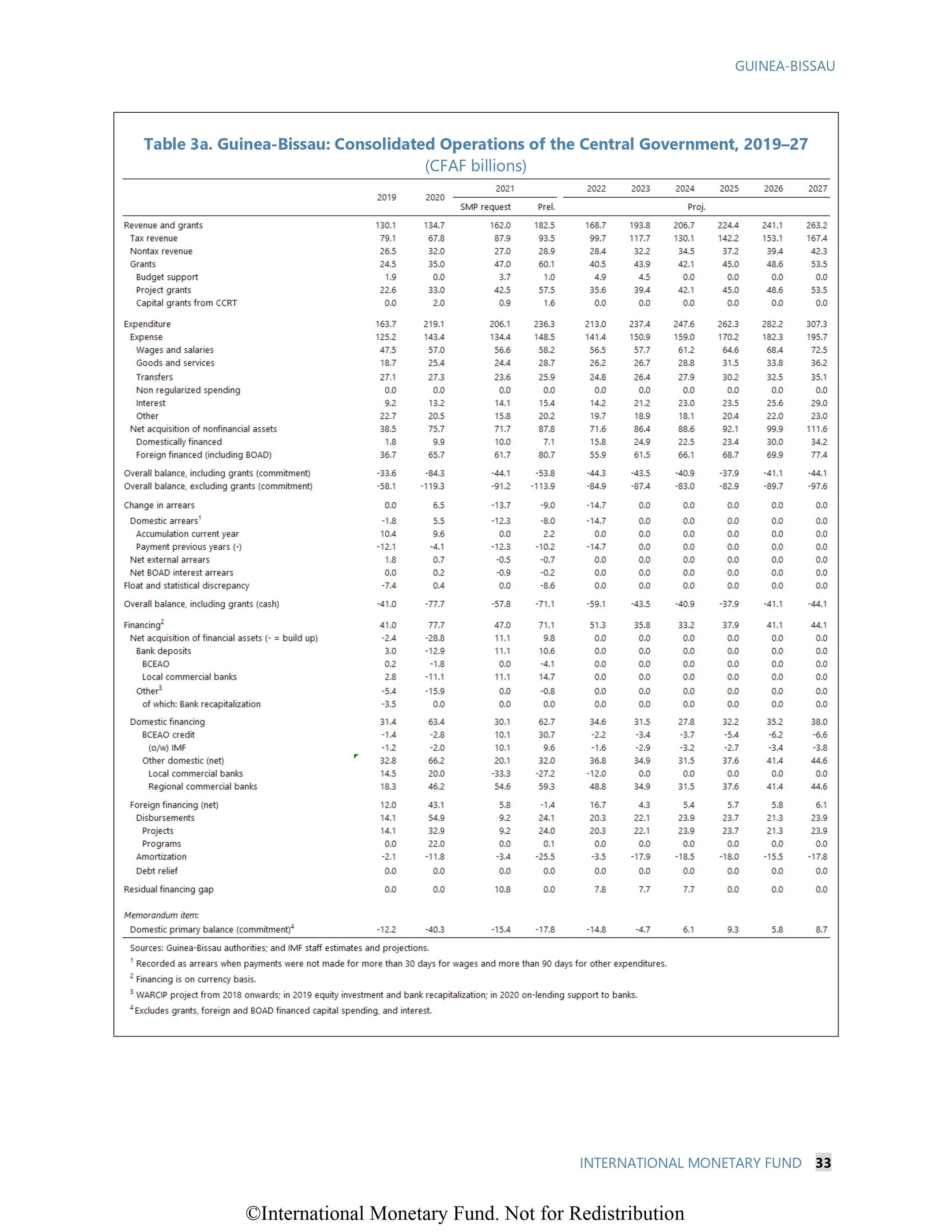

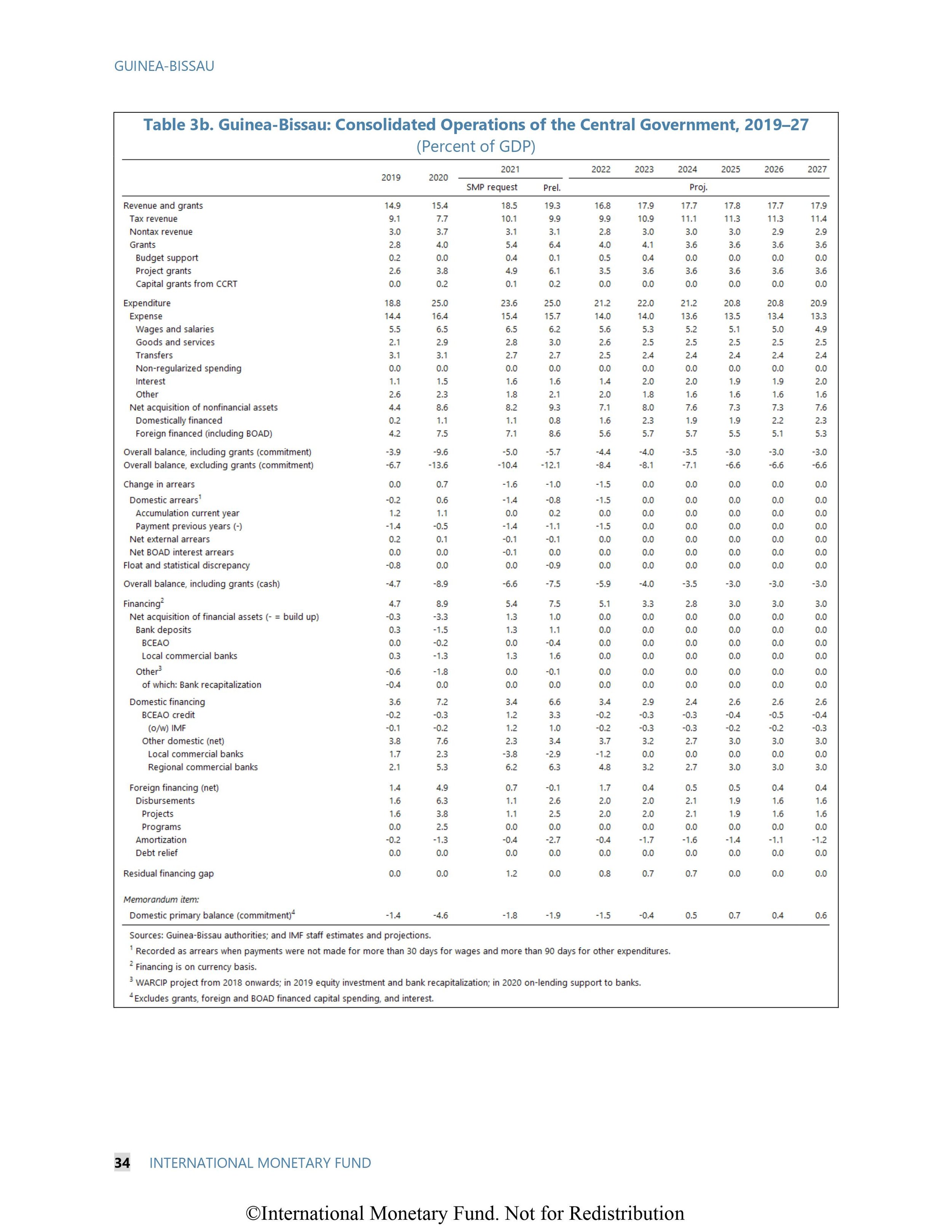

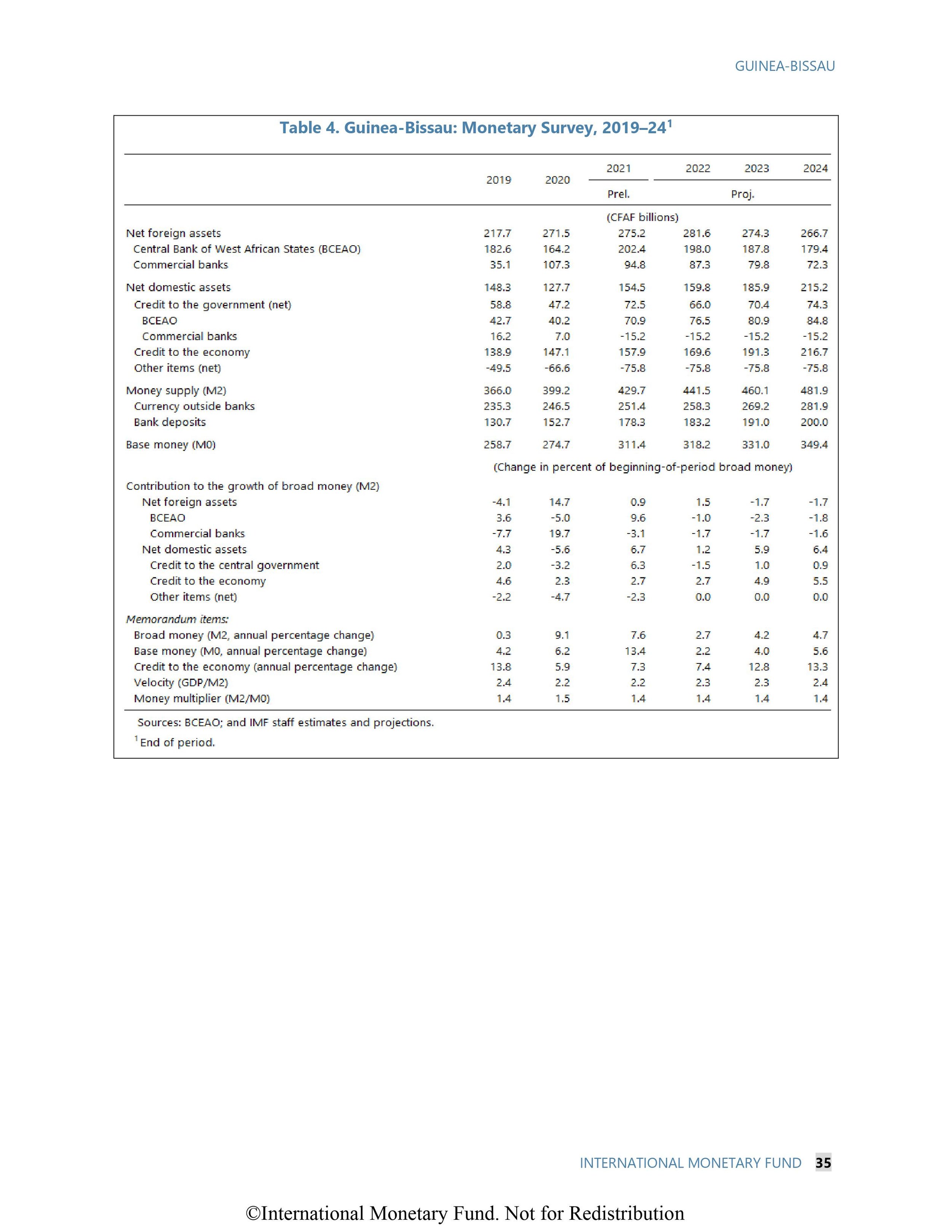

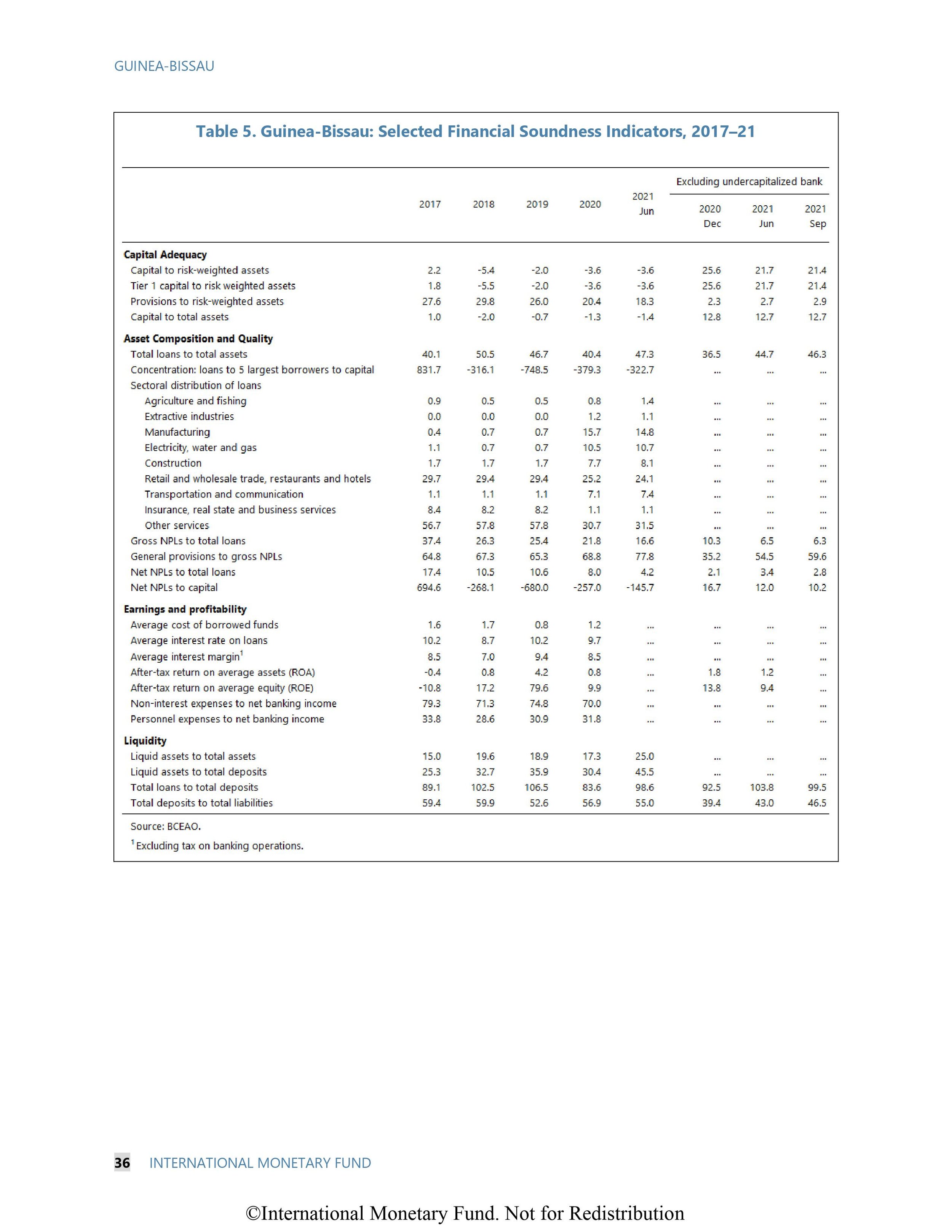

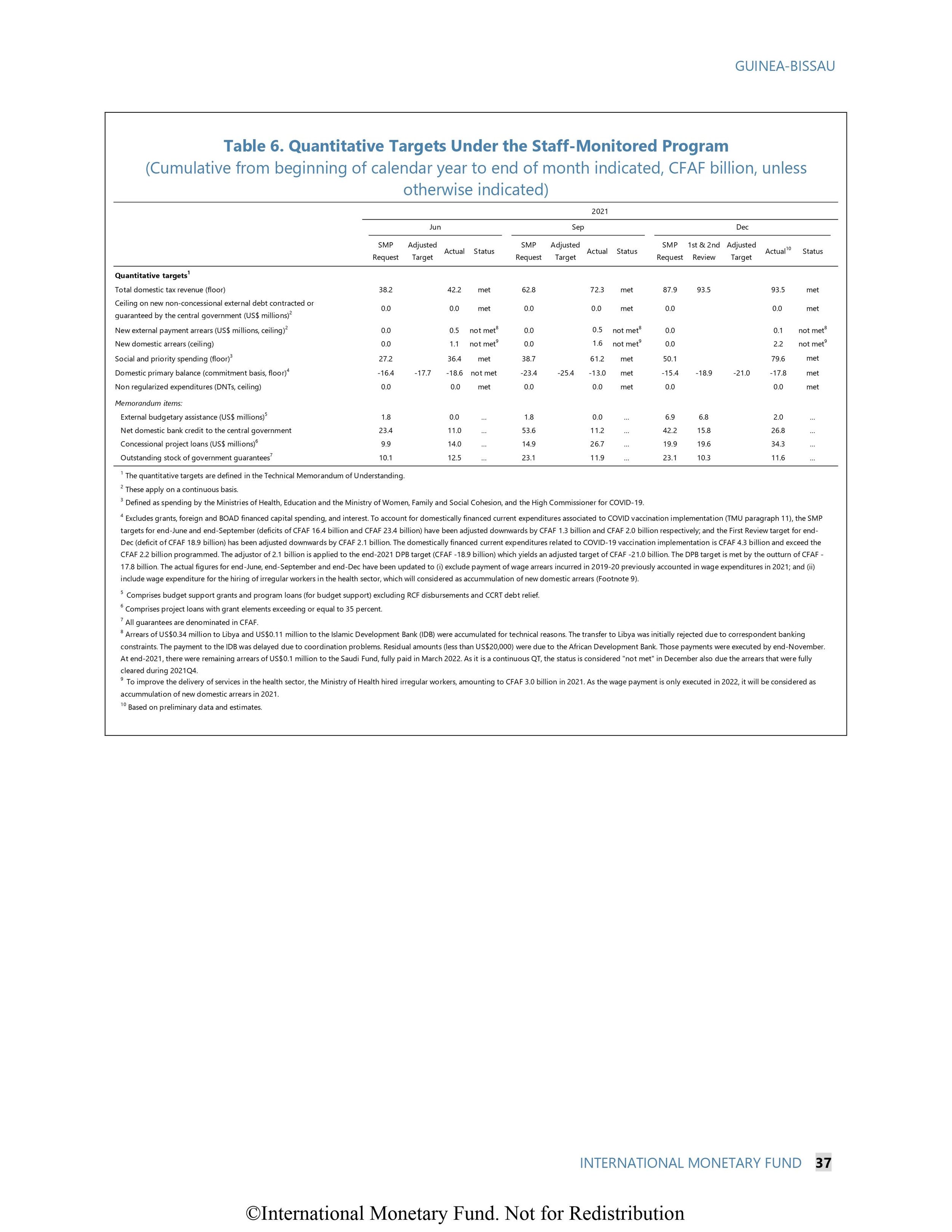

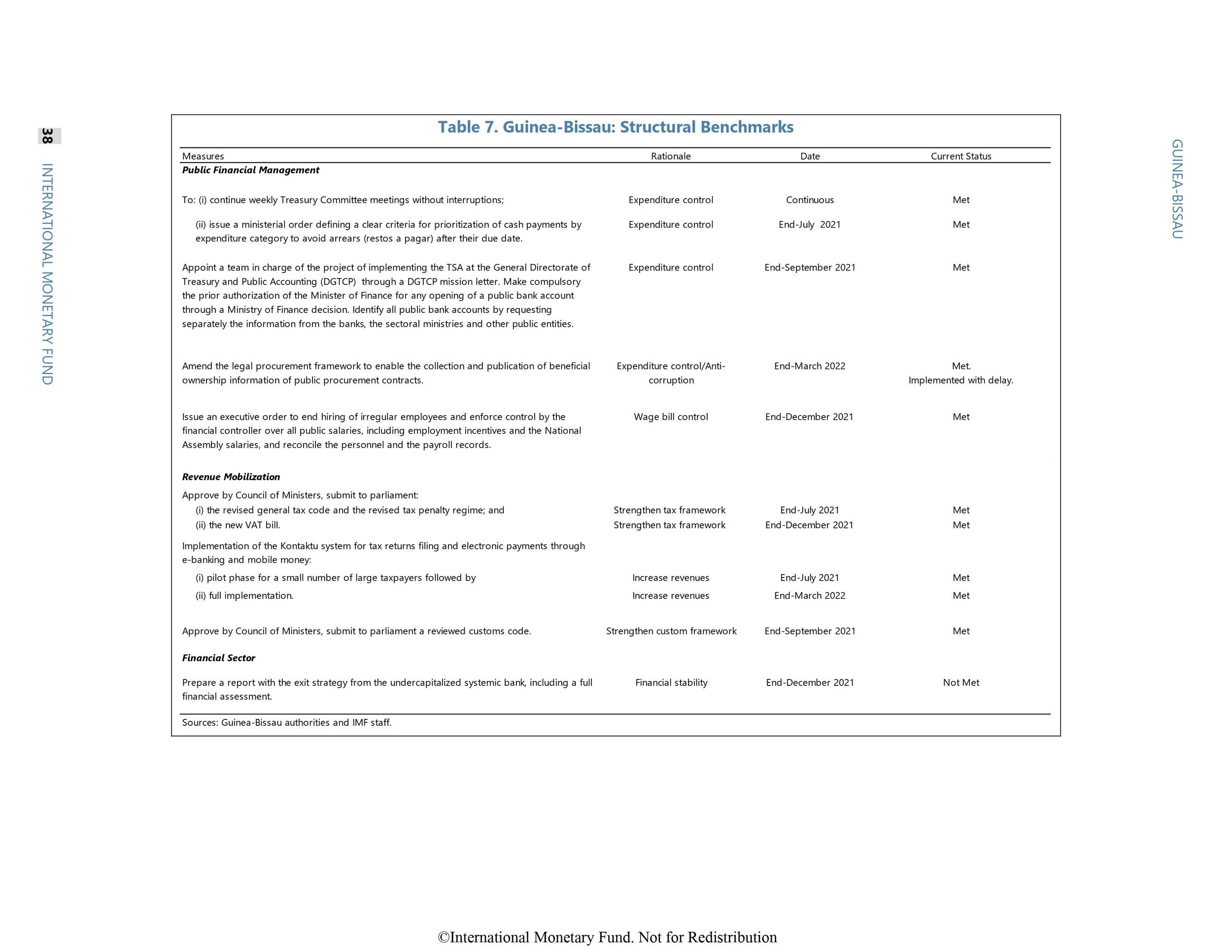

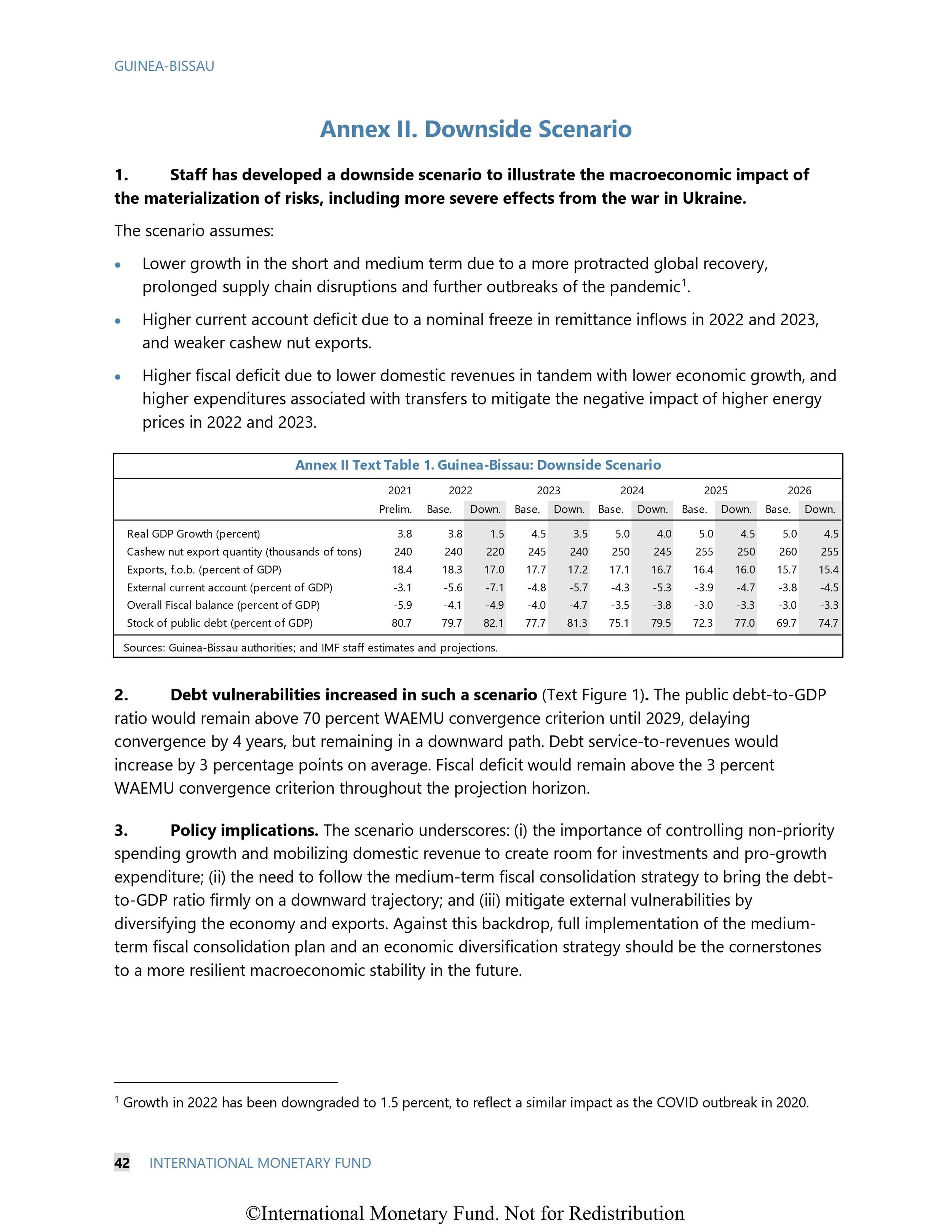

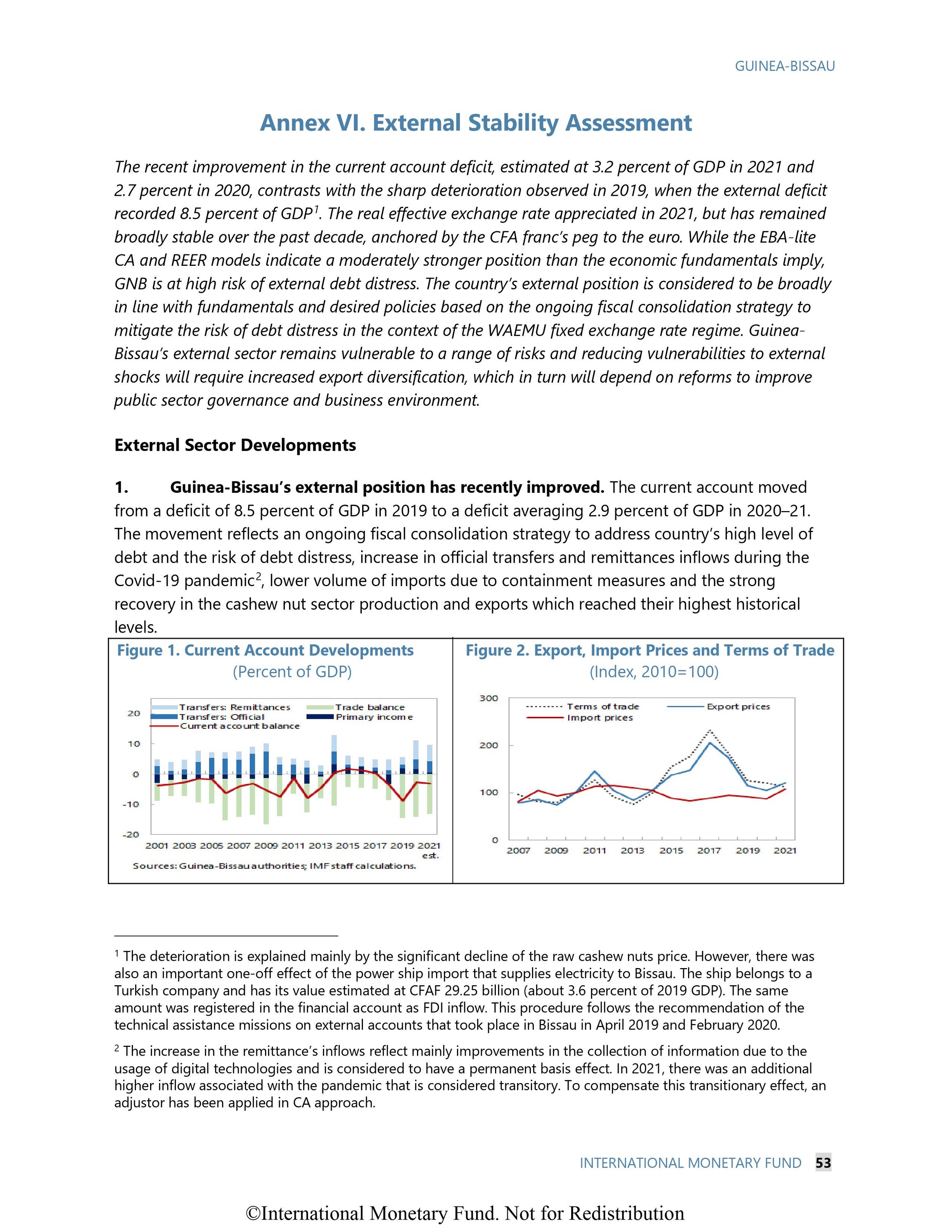

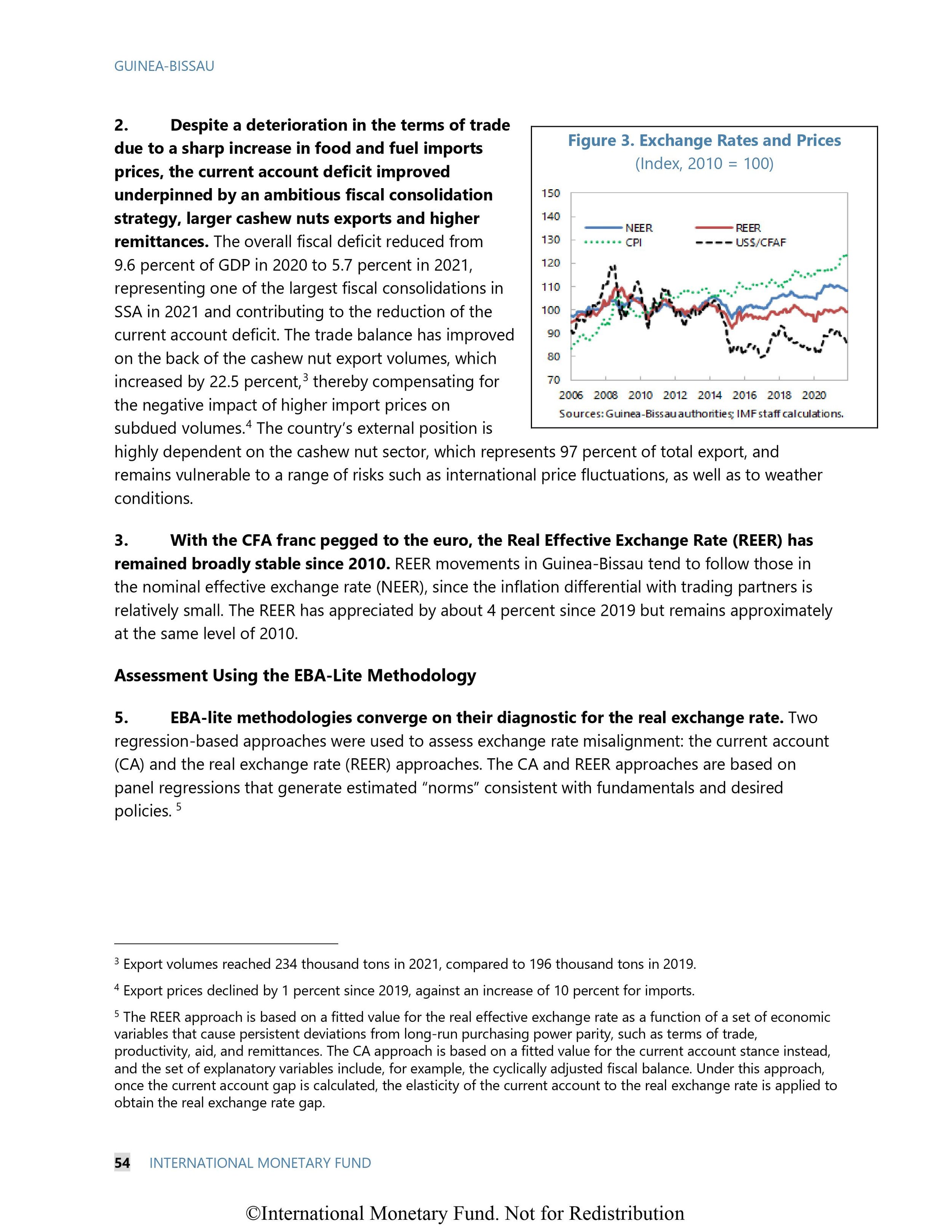

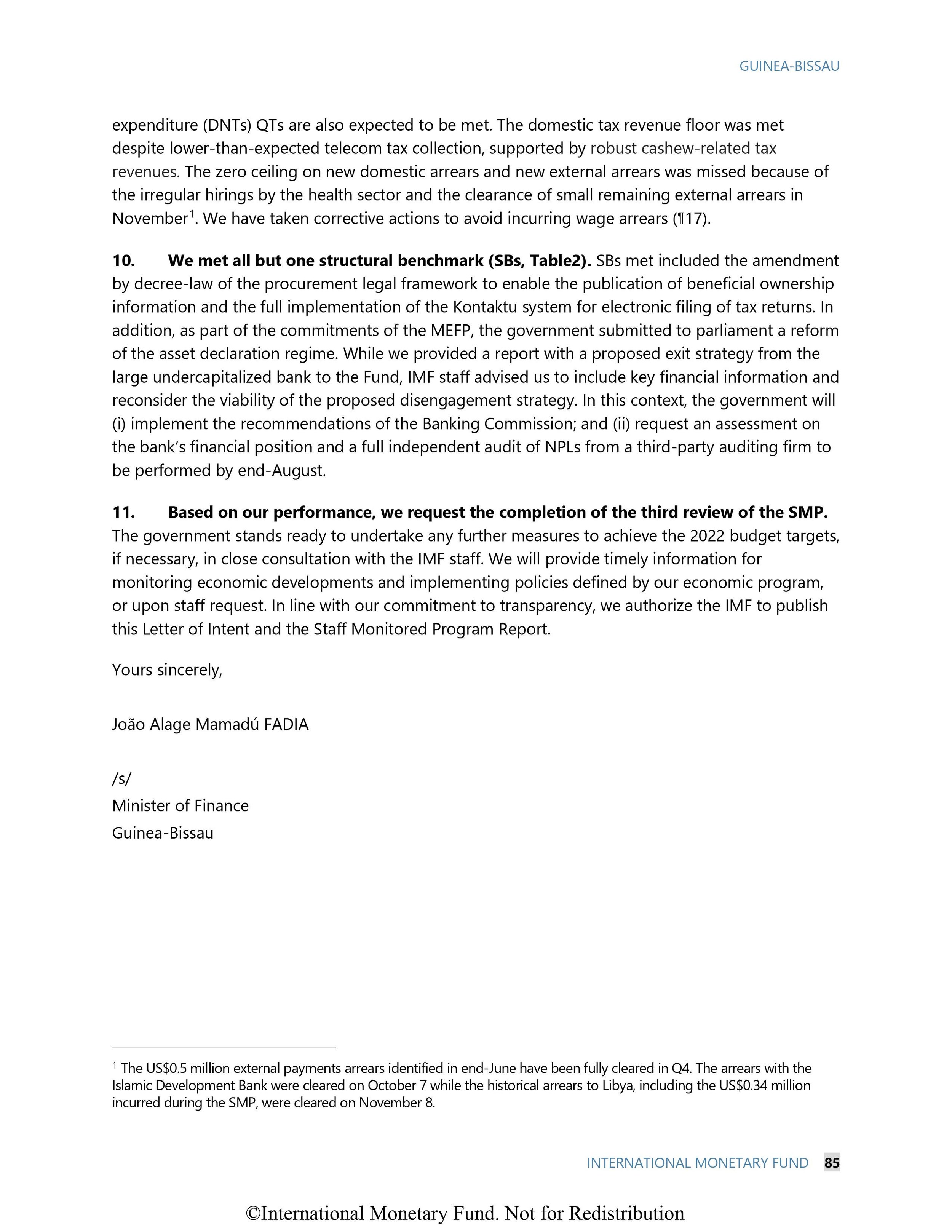

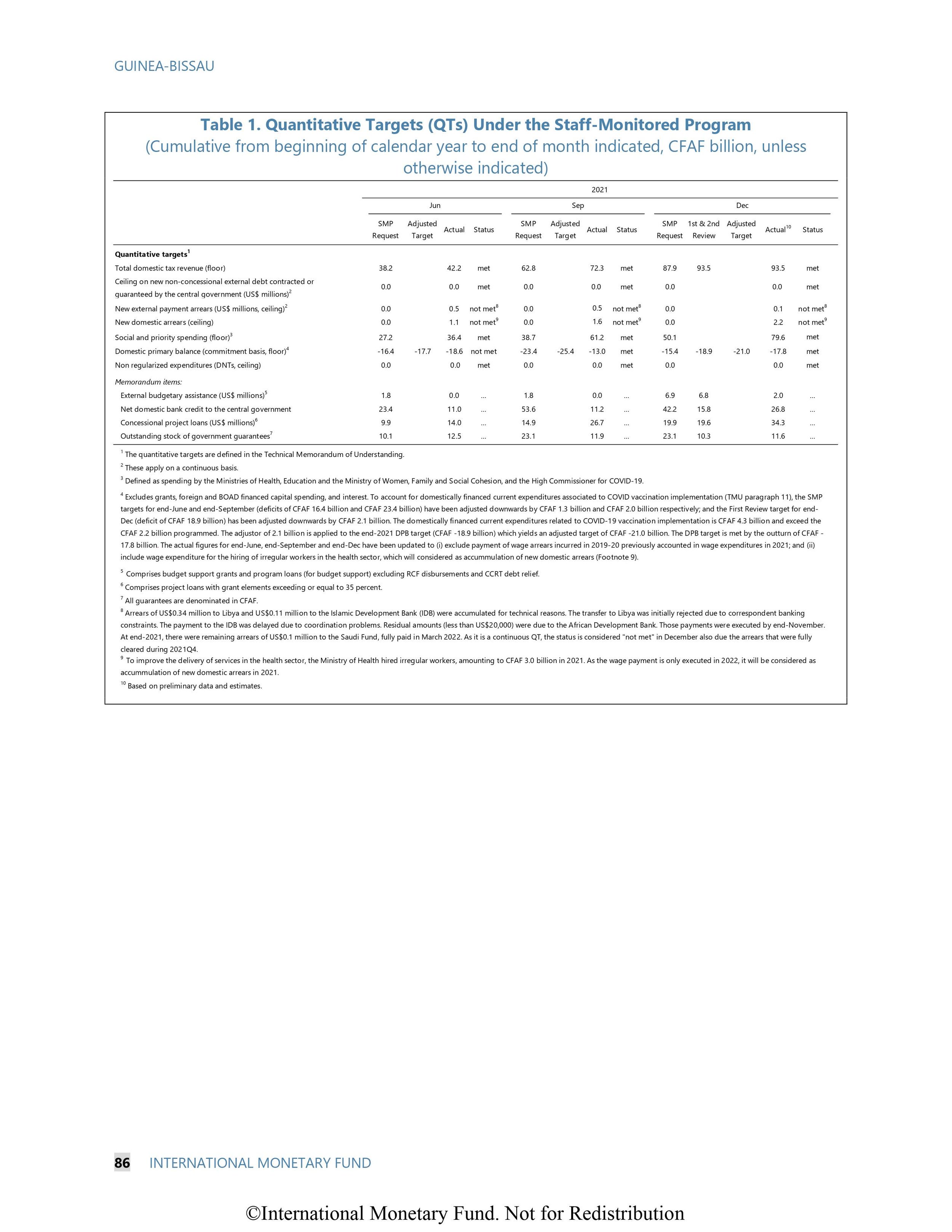

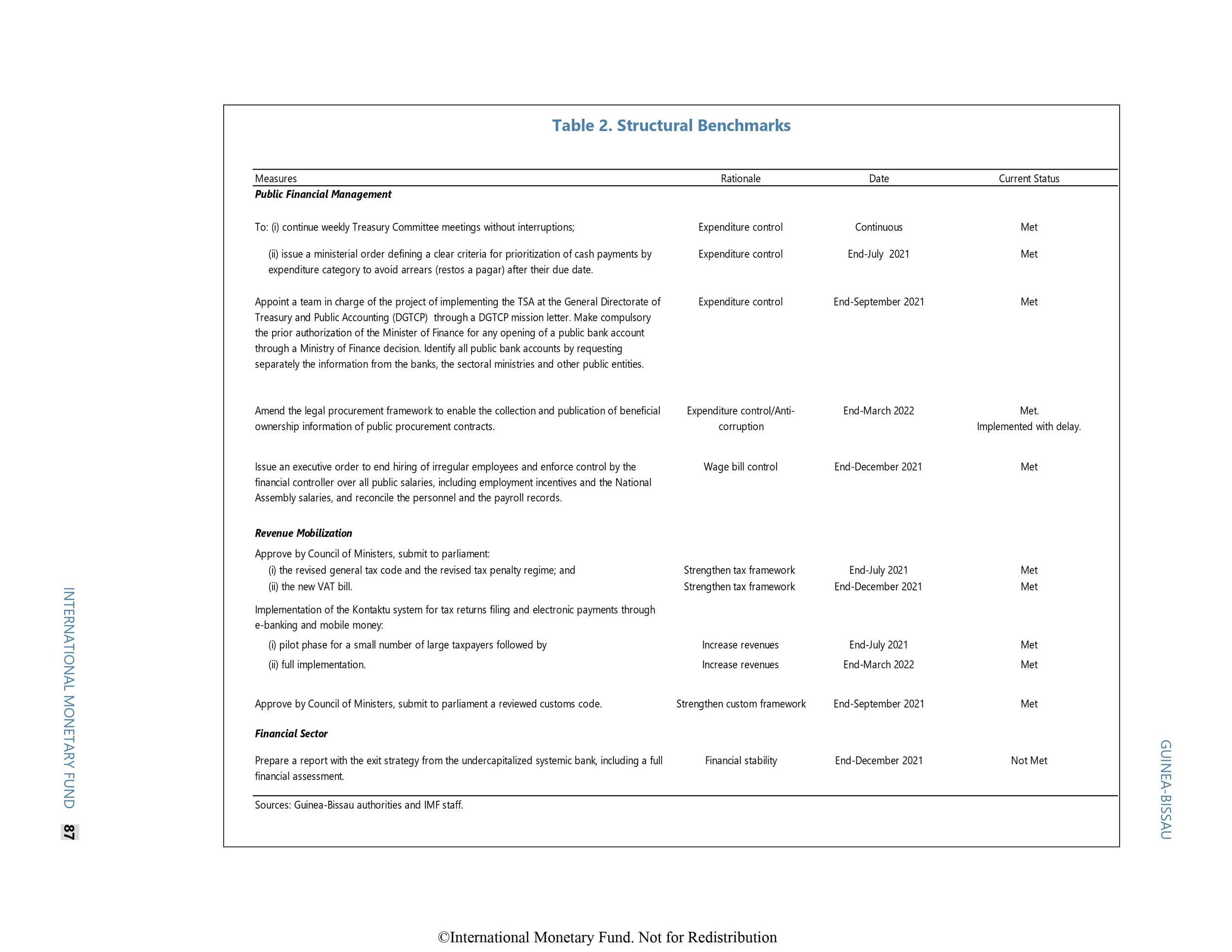

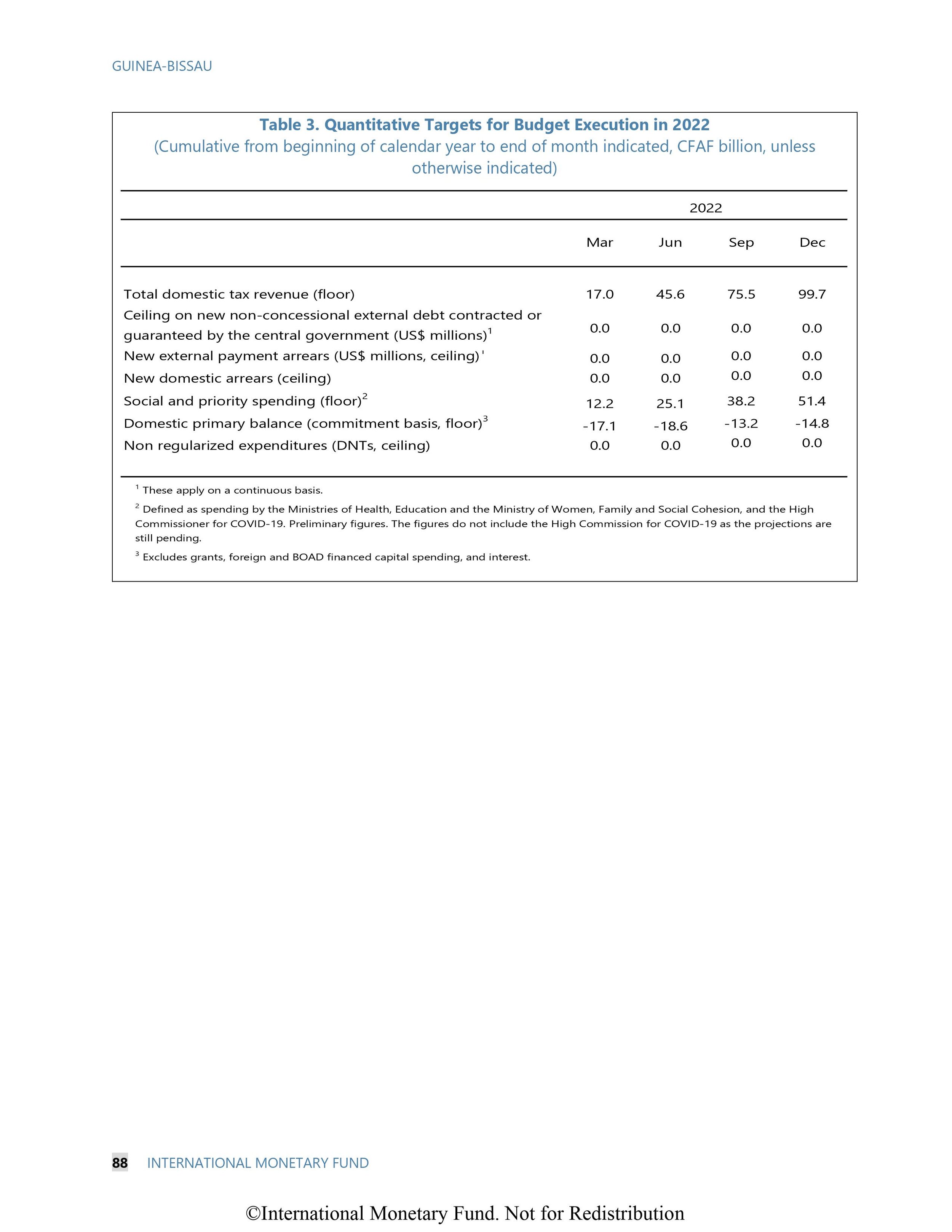

Now consider that Guinea-Bissau: 2022 Article IV Consultation and Third Review under the Staff-Monitored Program highlighted that,

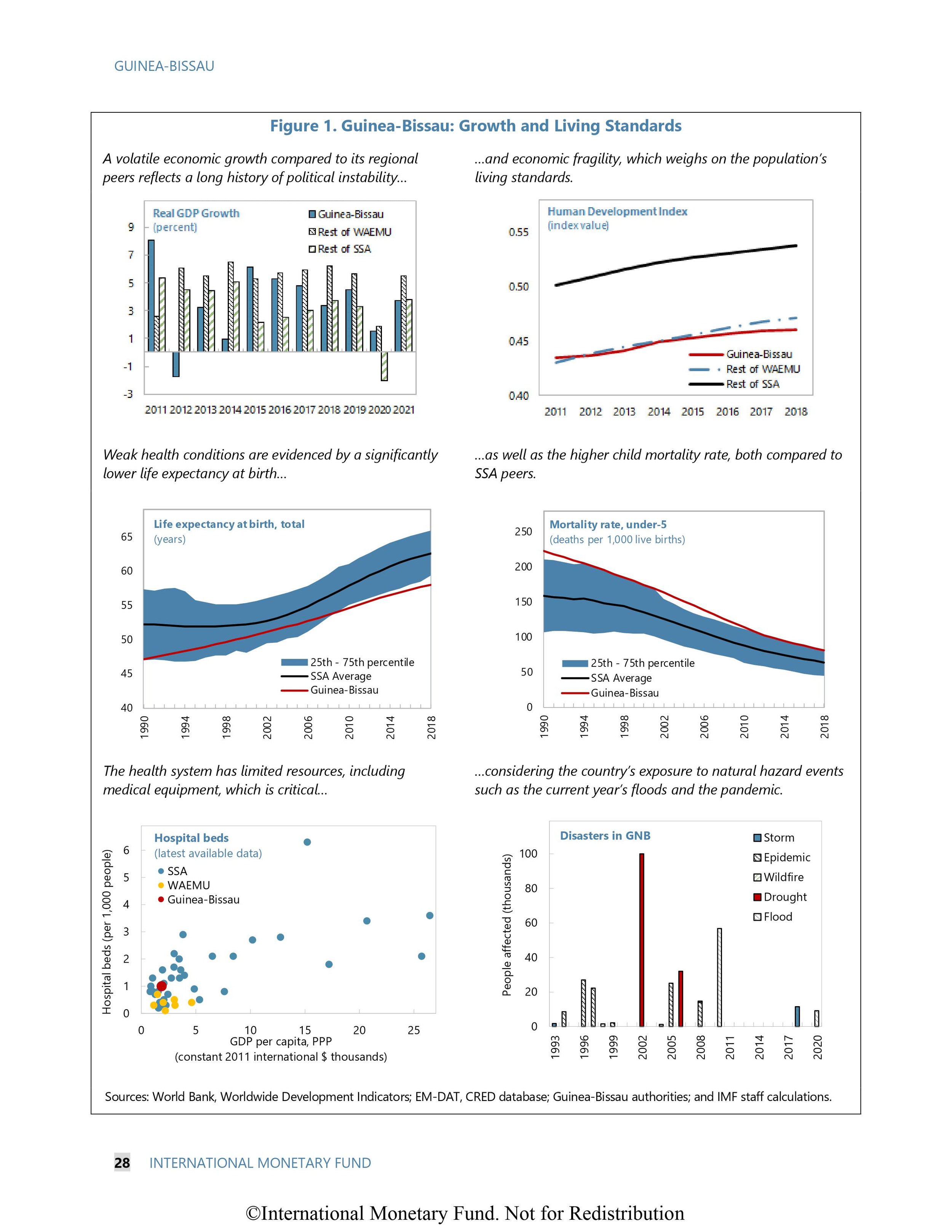

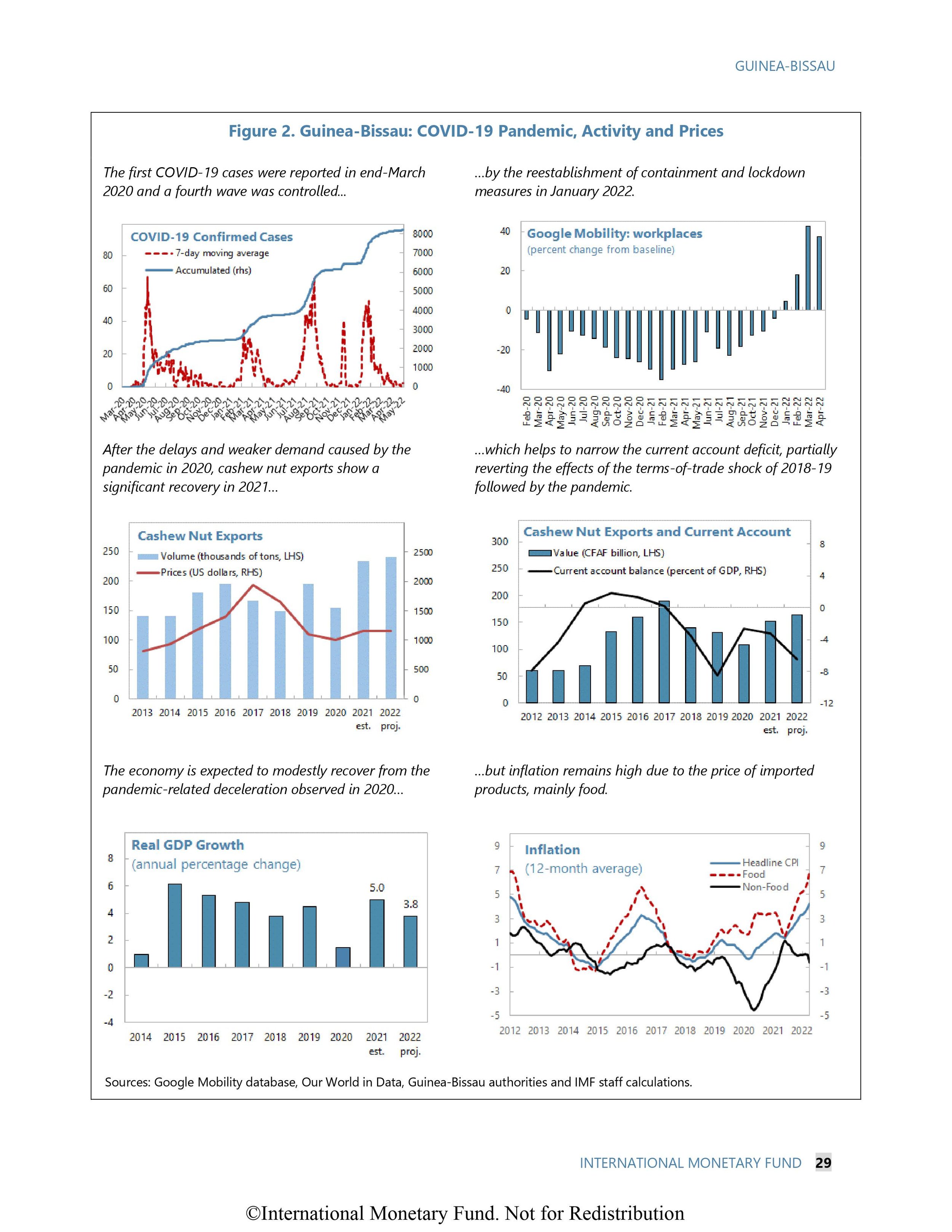

“External current account slightly deteriorated in 2021 despite of a record cashew nut campaign and remittances. Cashew nut exports have increased by 39.9 percent in 2021, compared to 13.2 percent growth of imports, and reduced the trade balance deficit. Workers' remittances reached a historical record level at 7 percent of GDP and contributed to the improvement in the secondary income account. As a result, the current account deficit is estimated to have reached to 3.2 percent of GDP. The August 2021 SDR allocation contributed to closing the external financing gap and enabled the authorities to pay debt service of BOAD —the regional development bank—for 2021 and 2022.

9. The stock of public debt increased slightly despite the improvement of the fiscal position. The stock of public debt increased by 2.0 percent of GDP in 2021 with an increase in domestic debt corresponding to the SDR allocation on-lent by the BCEAO. . . .

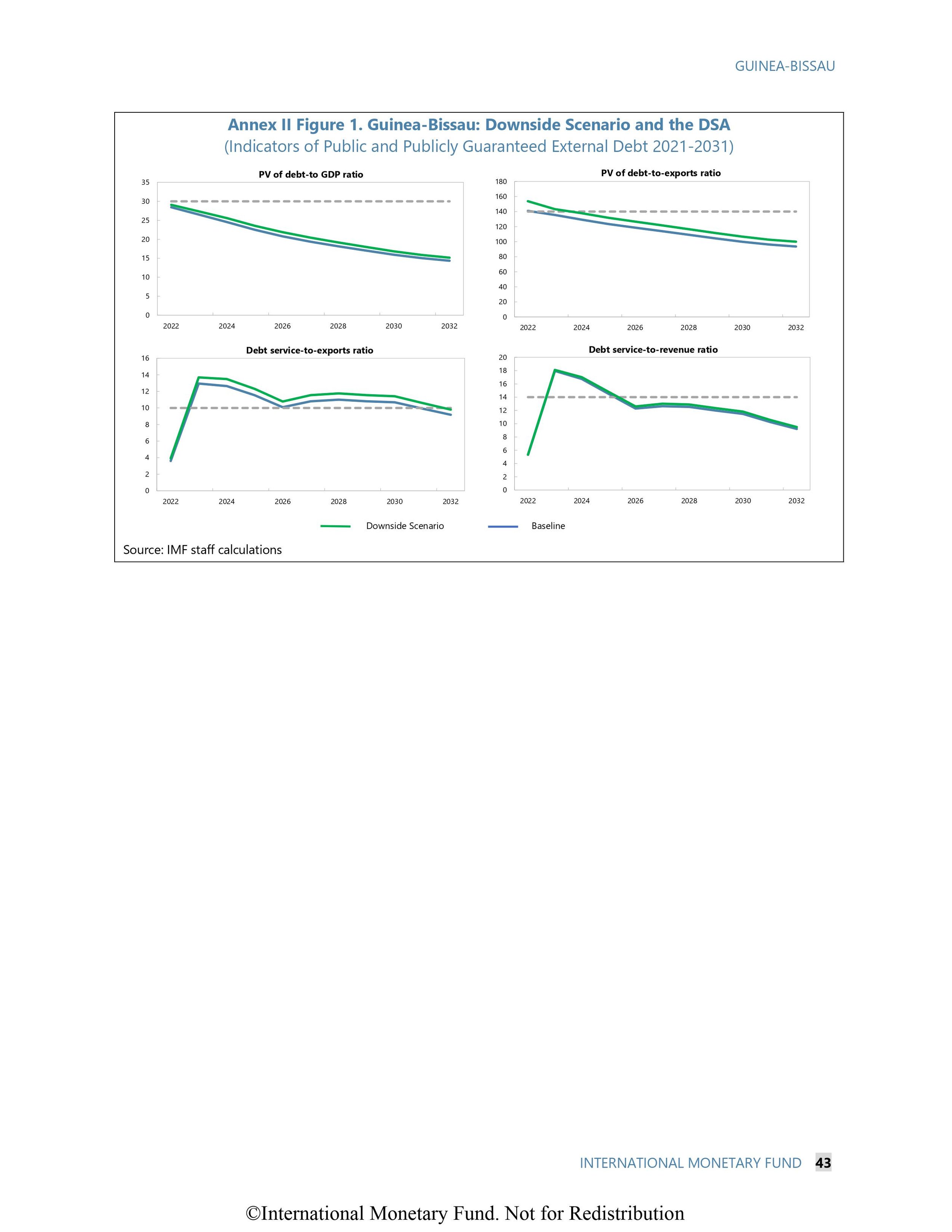

32. Guinea-Bissau is at a high risk of external and overall debt distress. With the reclassification of BOAD, the share of external debt reaches 40.1 percent of GDP (from 26.7 percent in the July 2021 DSA). The risk of external debt distress is high because the indicators based on the debt-service ratios breach their indicative thresholds under the baseline. Overall risk of debt distress is also high because the PV of public debt relative to GDP remains well above its indicative benchmark throughout the projection period (DSA). . . .

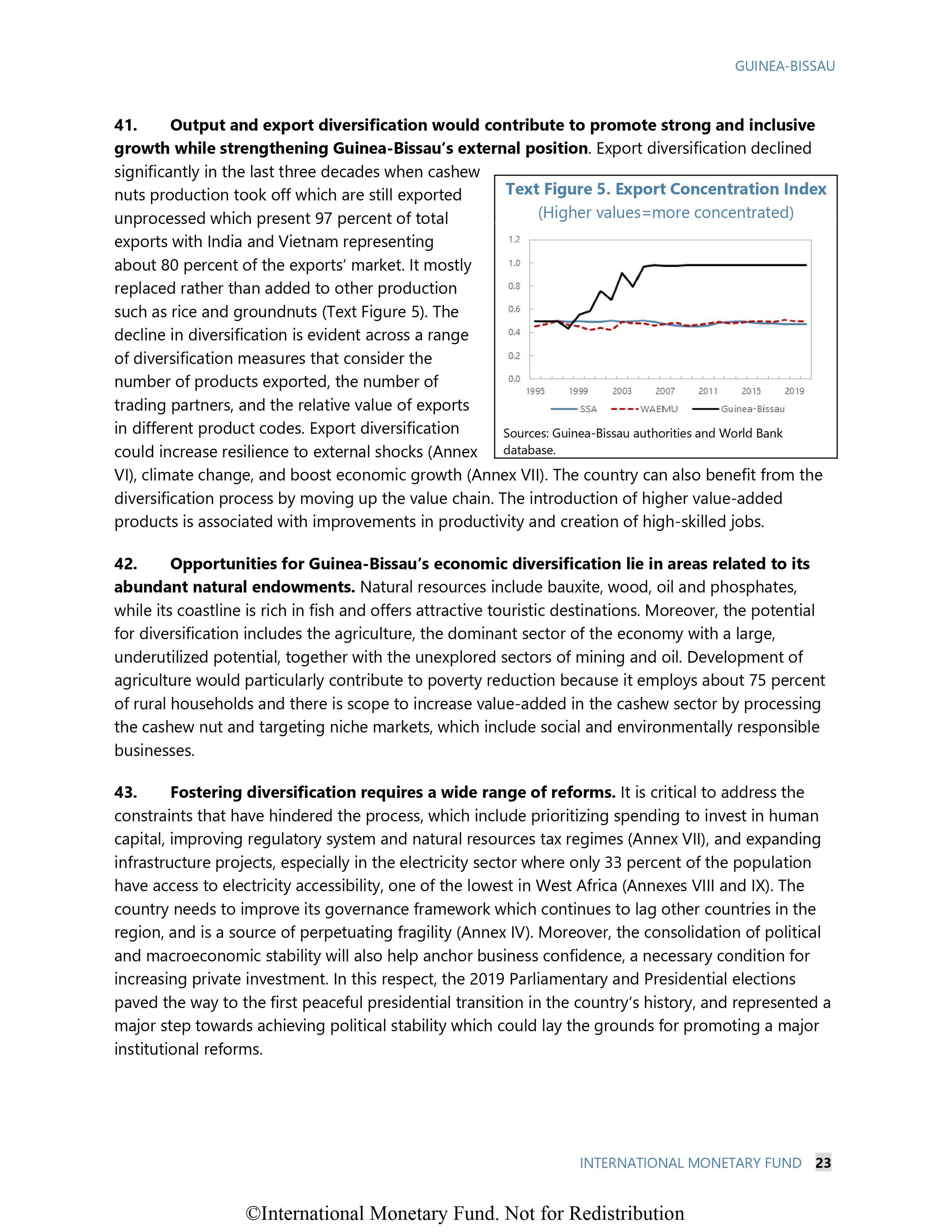

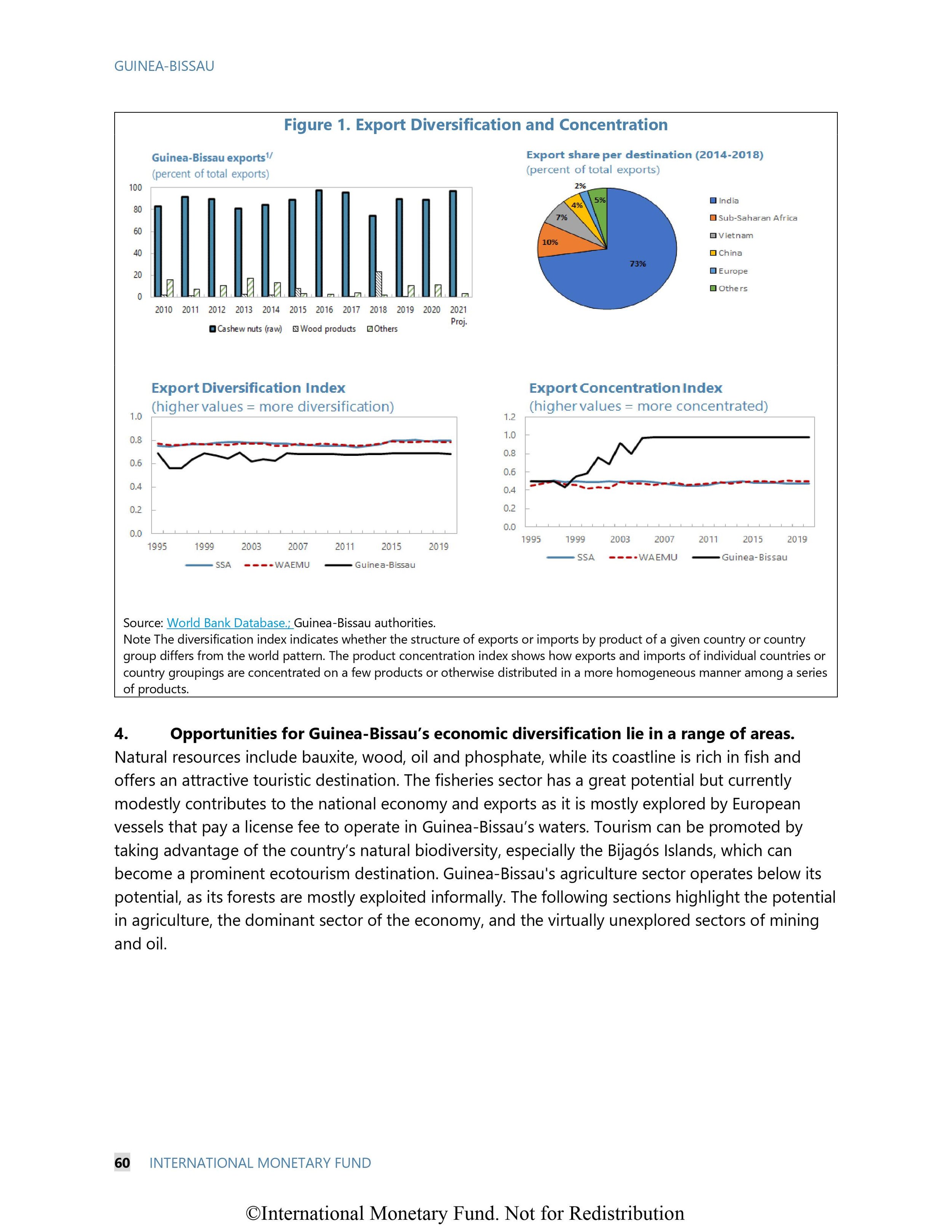

41. Output and export diversification would contribute to promote strong and inclusive growth while strengthening Guinea-Bissau's external position. Export diversification declined significantly in the last three decades when cashew nuts production took off which are still exported unprocessed which present 97 percent of total exports with India and Vietnam representing about 80 percent of the exports' market. It mostly replaced rather than added to other production such as rice and groundnuts. The decline in diversification is evident across a range of diversification measures that consider the number of products exported, the number of trading partners, and the relative value of exports in different product codes.”

Thus, despite a record cashew nut campaign and a 39.9% increase in cashew exports, public debt increased even while profits were used to pay debt service to the regional development bank.

Meanwhile, cashew funds continue to pour in. In February of 2022, O Democrata reported that the National Cashew Agency of Guinea-Bissau made plans to boost the productivity of farms from 300 kg of cashew nuts per hectare to 1,500 kg. The newspaper quoted the head of the agency, Caustar Dafá, as saying another intention is to improve the quality of the cashew nut crop using techniques appropriate for Guinean producers. Mr Dafá said his agency had agreed in January to form a partnership enabling the transfer to Guinea-Bissau from Brazil of technology for machinery for processing cashew nuts. Alanso Fati, President of the National Association of Farmers of Guinea-Bissau, ‘Guinea-Bissau needs to invest more in technology to increase its output of cashew nuts.”

The Hindu Bussiness Line reported that

“‘Beta Group, the Kerala-based food company, which owns the Nut King brand, will be setting up an industrial unit in the West African country of Guinea-Bissau for cashew business. The company is all set to sign a $100 million MoU with the Government of Guinea-Bissau over a period of five years to procure, process, and export value-added cashew, mainly to the US and China markets,’ said J Rajmohan Pillai, Chairman, Beta Group.”

In October of 2022, China-Lusophone Brief reported,

“Chinese state-owned company Grupo Human Construção e Investimentos has agreed with the authorities of Guinea-Bissau to buy the country´s cashew nuts production and later build cashew processing units. Grupo Human signed two memoranda of understanding with the ministries of Commerce and Energy and Industry of Guinea-Bissau, after four days of market prospecting in the country. Abdu Jaquité, delegate of the Government of Guinea-Bissau to the Permanent Secretariat of Forum Macau for the Economic and Trade Cooperation between China and Portuguese-speaking countries, told RFI that initially the Chinese will buy practically the entire production of cashew nuts.

In a second phase, Hunan plans to build processing units in the country, Jaquité said at the signing of the agreements. “They want to buy, if possible, 250,000 tons, which means practically all agricultural production”, the delegate underlined, adding the Chinese plan includes “to establish a factory for processing cashew nuts right here in Guinea-Bissau”. The Chinese province of Hunan, RFI added, is available to serve as Guinea-Bissau’s gateway to the world’s largest market with around 1.5 billion consumers.”

The question must be asked, in whose interest is all this cashew investment for? Is this any different from the redemptive and extractive mono-mercantilism model that Cabral identified in the 1960’s? Does increased investment in cashew value-added infrastructure address the priority long-term problems of Guinea Bissau? Does it not, in fact, make the people of Guinea Bissau even more dependent on a single crop?

And where do the profits go besides to the development banks? To answer this question, one must understand who owns the land and the farms. In Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop the authors state,

“At the end of 1974, marking the end of the colonial era, several hundred hectares of cashew orchards had been planted, but no industrial processing of cashew nuts or apples was carried out. The amount of raw cashew available was still not enough to feed a decortication unit with a capacity considered economically viable at the time. Thus, the impetus for development of cashew gained during the 1960-74 period, was dampened in post-independence. However, some non-governmental organizations and cooperation agencies developed a relevant action using cashew in the context of forest interventions. The use of cashew trees as a cash crop, in forest protection schemes or as a way to recover soil fertility in fallows was stressed. Cashew was considered an important species to be used to restrain deforestation, because of its acceptability by the peasants. “

Here it should be noted that, according to some studies, the rate of deforestation has increased from about 2 percent per year between 1975 and 2000 to 3.9 percent over the 2000 to 2013 period. Overall, Guinea-Bissau lost about 77 percent of its forests between 1975 and 2013; only 180 sq km remain, mainly in the south near the Guinea border. Likewise, woodlands regressed by 35 percent over the 38 years, a loss of 1,750 sq km.

The authors of Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop continue:

“A semi-manual decortication unit with a capacity of 250 tons per year and a bottling line for cashew apple juice and jams were built on Bolama Island in the late 1970’s with Dutch co-operation. Although this plant has proved to be economically unsustainable, its implementation was a strong boost to cashew cultivation.

By the mid-1980s, two factors gave new impetus to the intensity of planting and trading in the domestic market. The first was a non-organized race for the occupation of land by villagers, as a result of a significant increase in land grants to commercial farmers or "ponteiros" by government authorities. Since 1984, government policy aiming to increase agricultural production initiated large concession grants and, as of 1987, land distribution increased. It was estimated to represent around 300,000 ha out of an estimated agricultural area of 1,100,000 ha and 1,400,000 ha of silvo-pastoral land. These lands, contrary to what happens with traditional farmers, were demarcated and registered in the Land Registration Services of the Ministry of Public Works.

The gaps in the land property law, which overlooked customary rules that grant property rights to those who planted permanent crops, meant that traditional farmers tried to secure land to ensure their access to it. Cashew, due to its hardiness and quick growth, was an obvious choice. The second driving force was the authorities’ initiative to curtail cashew smuggling to Senegal, due to increased internal consumption and the revival of the cashew decortication factory in the Sokone province of that country. An informal barter trading practice was thus put in place, wherein cashew was exchanged for rice at a ratio of one to two, which evolved due to the relative change of the quotations of the two commodities to one to one. More recently, data from a country report for 2013 report a deterioration in the terms of trade, 1kg of rice being exchanged for up to 3 kg of cashew (Cont and Porto, 2014).

Another factor which can help to understand the continuous cashew expansion and consequent decrease in production of staple crops. It is the comparative advantage of cashew in terms of the differential days invested by cultural cycle and added value of the agricultural work invested per day. Since the traditional farmers’ strategy was to optimize work invested in agriculture, we can see a strong drive to shift from traditional agricultural practices to cashew cultivation. . . .

Cropping systems and cultivated varieties

Two main types of cropping systems co-exist in Guinea-Bissau: the peasant and the commercial system, locally known as "ponteiro". The vast majority of cashew orchards are owned by small farmers in villages all over the country. The average smallholder plantation is thought to cover 2-3 hectares, though farmers often have no idea of the size of their planted area.

The process of cashew expansion usually starts in the land closest to the center of villages and expansion follows a centrifugal trend. A piece of fallow land or semi-natural woodland or savanna woodland is prepared by cutting down the woody vegetation, which is burned by the end of the dry season. In the most frequently used system, cashew is intercropped in the first two or three years with food crops (e.g.: rainfed rice, millet, sorghum, maize or groundnuts). Every year a new piece of land can be prepared and sown with cashew and food crops. Cashew trees are sometimes also planted as live fences, despite the fact that their spreading habit makes them unsuitable for close spacing.

Plant spacing is traditionally very close (e.g.: 3-5 m), with roughly defined or even non-existent rows. However, in recent years this trend has begun to change, with greater plant spacing and the use of well-defined rows in the younger cashew orchards. Within the lines the trees are often paired because two seeds are sown per hole with the idea that at least one may survive. Farmers who sow close together often do so following the advice to sow a large number of trees and thin them later, which is a good proposition for rapid establishment of a crop, minimizing costs of weed clearing and avoiding severe development of termite colonies. Unfortunately, many farmers never get around to thinning the trees.

At the level of the small farmer there is no varietal selection and no care is taken in the establishment of orchards. There is also no support dispensed by the very weak structures of agricultural research and extension in the country. These orchards, owned and explored at the family level, are small, rarely exceeding a few hectares and growing with virtually no agro-chemical inputs.

To tackle some of the problems mentioned, in the 1990 decade the Trade and Investment Promotion Project (TIPS) included an extension component that promoted cashew planting seminars around the country, nursery establishment and post-harvest technologies. However, at the end of the project, no ministry took over the continuation and consolidation of the objectives. Therefore, only a minority of farmers had incorporated the knowledge made available.

At the "ponteiro" or commercial system level, a number of plantations are distributed throughout the country, with great heterogeneity in terms of size and care dispensed to the orchards. The orchards owned by small “ponteiros’ are established using a method similar to that of the traditional farmers, with no care for the choice of seeds and close tree spacing. Conversely, in a few agro-industrial farms whose extension surpasses 1000 hectares in some cases, care has been taken in the selection of parent material and in adequate tree spacing. Nevertheless, in both peasant and commercial systems no agro-chemical inputs were used in the cashew orchards. Thus, the Guinean cashew nuts are organic and can fetch a higher price if suitably processed and marketed, and comply with stringent hygiene standards as demanded by international markets. However, this is yet to be fulfilled. . . .

Cashew tree and land ownership

In Guinea-Bissau the land is formally considered state-owned but, as in most of West Africa, consuetudinary land tenure practices are linked to the planting of perennial plants, in particular fruit trees (Fenske, 2011). In times of increasing population density, and when the sale of land is becoming a common practice, cashew orchards can act as land tenure insurance (Temudo and Abrantes, 2012). In this respect, the cashew nut tree possesses several advantages: it is a rapid growing tree which does not require much care or manpower to establish and maintain and, above all, produces a non-perishable fruit with an assured market. On the other hand, cashew works like insurance for the elderly, in times of exodus of young males to the towns, because it requires little manpower that can be largely provided by women and children (Lundy, 2012). The role of cashew trees in the marking of land tenure can thus explain, to a certain extent, the success of the crop and is a matter that requires further study.

Trade, exportation and local processing of cashew

The outflow of annual production of cashew nuts occurs during the so-called "cashew campaign", which runs approximately from March-April to August. During this period, small free-lance buyers and officers of medium sized companies travel the country acquiring cashew nuts or exchanging them for rice.

From 2004 onwards, the cashew nut market became relatively liberalized and less dependent on rice bartering and more on a cash basis than previously. In approximate terms, the overall marketing chain from farm to port is quite short. There are up-country buyers acting on behalf of urban buyers; raw cashew nuts are delivered to town warehouses where they may be further dried, bagged and consolidated in loads, or sent directly to exporters in Bissau. Exporters may or may not re-bag the cashew nuts and then sell them to international dealers or processors for shipment to India. Participation in this chain of commercialization is licensed and each of the agents in the chain has to pay a fee to the Ministry of Commerce and the Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (CCIA). As of 2004 there were about 300 registered buying agents and 40 exporters.

Fleeing from this general scheme, rural farmers maintain the custom of receiving a loan on rice on account of cashew nuts to produce the next season, often at an exchange ratio unfavorable for them. In years of low cashew nut production, this practice can have serious consequences for small farmers, specifically at the food security level.

The absence of a legislative and regulatory framework to structure the cashew market, a commodity that commands such importance to the country’s economy is surprising, and is a situation which should be remedied so that it can function with integrity and transparency of price formation and transactions. Without this market structuring, for which there are already positive examples in Africa, it is difficult to attain a fair partition of benefits for the majority of farmers.”

As per the Volza's Guinea Bissau Raw cashew nuts Exporters & Suppliers directory, there are 277 active raw cashew nuts exporters in Guinea Bissau exporting to 489 Buyers.

LION OVERSEAS PTE LTD accounted for maximum export market share with 146 shipments followed by DELTA STAR GENERAL TRADING LLC with 122 and OKI GENERAL TRADING LLC at the 3rd spot with 70 shipments.

ARREY AFRICA SARL is the largest cashew nut processor in the country. According to its website,

“Our company is located in Bula - Guinea Bissau. Arrey África has been operating a cashew nut processing plant with 5,000 m² of built area since 2015, and we have 225 employees.

In January 2021, we started the operation of another unit, in the same city, with twice the production capacity and forecast to hire 400 employees, with a built area of 7,000 m².

The Arrey Group also operates another factory in Brazil, EUROALIMENTOS, located in the city of Altos – Teresina/Piauí, with 400 employees and 15,000 m² of built area. For 25 years, it represents one of the most important industries in the state of Piauí.

Sustainability is part of one of our main goals; with this, we started the Bio project, through purchases from local cooperatives, where suppliers/producers are georeferenced, which demonstrates the origin and good practices of the products we process.

The AGRICERT certification gives us the right to guarantee the origin and qualty of our products.

Arrey África Company, together with the World Bank and the Private Sector Rehabilitation and Agroindustrial Development Support Project (PRSPDA), created a project within the cashew nut sector, directly linking farmers to the transformer in 2018.

The project has the help of 8 peasant cooperatives from two regions of the country (CACHEU and OIO).

In the same year of 2018, the orchards of 3,509 producers were georeferenced, and an area of 9987ha, which the Arrey Africa Company certified in organic cultivation through the Agricert certifier.

We have bio europa certificates, NOP, Haccp food safety certificate, and we are implementing the BRC, Smeta certificate… During the cashew nut season, Arrey África pays a bonus to the cooperatives, so that they are the ones who connect and transport the raw material from the producers to the factories, processing plants that Arrey has in the town of Bula, Comarca de Cacheu, where we process 4000MT of cashew nuts per year.

Arrey África this year 2022 will make available 6840m2 of its land in agreement with the city's school of agricultural technology for the cultivation of different vegetables and seedlings of the cashew nut tree for delivery to producers who join the project within the scope of improving the orchards of cashew.

Since 2015, our company has been exporting cashew nuts to several countries in Europe (Spain, France, Italy, Holland, Germany...), as well as the United States of America, Brazil and Asia.”

The Arrey Group includes Arrey Hotels, Arrey Construction, and Arrey Group Trade and Industry.

Alphonsa Cashew Industries, on its websites, states,

“The family has been in the cashew business since 1958. Alphonsa Cashew Industries was established as an independent business in 1986 by Babu Oommen under the patronage of his father and founder of the family business, Oommen Geevarghese. . . . Alphonsa is one of the largest direct procurers (on actual user basis) of Guinea Bissau raw cashew at the farm-gate level. . . . In line with our vision to vertically integrate our business and to create one of the most comprehensive traceability systems in the cashew industry, we started our Direct Procurement Programme in 2010 with our first procurement center being set up in Sampa, one of the most prominent cashews producing region in Ghana. This was followed by us expanding our direct sourcing footprint to Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Tanzania and Guinea Bissau. What started as a single company has today grown to 12 independent companies, each lead by a descendant of the founding family, that is collectively one of the largest business group in the cashew industry.We began our direct procurement in 2019 with sourcing and shipping activities based out of Bissau, the capital of the country. . . . We have an ownership or active engagement in all stages of the cashew value chain starting from procurement of the highest quality raw cashew nut at the farm-gate level from 6 origins to in-house processing in 13 processing facilities in India and distribution of superior quality cashew kernels to over 300 customers spread across 43 countries worldwide. Cochin Chamber of Commerce, one of the most reputed Chamber of Commerce in India, ranks us among the top 10 shippers of cashew from India. . . .”

Guinean economist Aliu Soares Cassama has stated, “Our economy has had a deficit in the trade balance for a long time. In other words, we import more and export less. We know that economic agents do not have purchasing power due to the total paralysis of the State, and this situation will further complicate the economic weakness that the country is experiencing.”

AMILCAR CABRAL HAS TAUGHT US HOW THE ECONOMY OF GUINEA BISSAU DEVELOPED FROM A CASH CROP MONO-MERCANTALIST SYSTEM STARTED BY THE EXPORTS OF PEOPLE, THEN PEANUTS, NOW CASHEWS. THIS IS PROFITED FOREIGNERS AT THE EXPENSE OF GUINEANS.